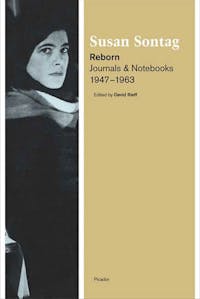

Reborn

Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963

Download image

Download image

ISBN10: 0312428502

ISBN13: 9780312428501

Trade Paperback

336 Pages

$25.00

CA$34.00

The first of three volumes of Susan Sontag's journals and notebooks, Reborn presents a constantly surprising record of a great mind in incubation. It begins with journal entries and early attempts at fiction from her years as a university and graduate student, and ends in 1963, when she was becoming a participant in and observer of the artistic and intellectual life in New York City.

Reborn is a kaleidoscopic self-portrait of one of America's greatest writers and thinkers, teeming with Sontag's voracious curiosity and appetite for life. We watch the young Sontag's complex self-awareness, share in her encounters with the writers who informed her thinking, and engage with profound challenge of writing itself—all filtered through the inimitable detail of everyday circumstances.

Reviews

Praise for Reborn

"Sontag's Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963, edited by her son, David Rieff, is a fascinating document of her apprenticeship, charting her earnest quest for education, identity, and voice. The volume takes us from her last days at North Hollywood High School to the year that, now living in New York, she published her first novel, The Benefactor."—Darryl Pinckney, The New Yorker

"Susan Sontag's presence, in essays, interviews, fiction, film, and theater, wove itself so firmly into our culture that when it vanished upon her death in late 2004, one became abruptly aware of the delicacy of the fabric. She was for many a focal point—someone whom readers and commentators enjoyed revering, dismissing, complaining about, being exasperated, or infuriated, or amused, or electrified by—and she was a focusing consciousness; her stature a writer and the value of her work have been, and no doubt will continue to be, debated, but what is beyond dispute is that she suggested, monitored, and even, to an extent, determined what was to be under discussion. She seemed to be at least twice as alive as most of us—to know everything, to do everything, to be inexhaustibly engaged. Her arresting appearance was familiar even to many nonreaders from the photographs that recorded it over several decades and registered the glamour and magnetism—the sheer size—of her personality, and her celebrity was all the more potent and irreversible because the place she occupied was so far outside the usual radius of the spotlight. And also because it was a general combustion of her style, her brain, her concerns, and her looks—rather than any particular attribute or accomplishment—that gave off all that dazzle. Sontag's own apparent conviction, sustained until several weeks before she died, was that the laws of mortality would be, if not canceled, at least suspended in her case. And rather than resolving her evident ambivalence about exposing her private writings, she allowed death to bequeath the ambivalence to her son, David Rieff. This we adduce from Rieff's decorous and deeply moving introduction to Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963, the earliest and first to be published of three volumes, which begins when its author was just shy of fifteen . . . The diaries contain (among plenty of other sorts of things) passages that concern's Sontag's—largely anguished—love affairs with several women, her abrupt and painful seven-year marriage to the scholar and cultural critic Philip Rieff, and, inevitably, their son. The experience of reading the diaries, even for a disinterested party, is intense as well as anxiously voyeuristic; small wonder that the tone of Rieff's introduction is sometimes that of someone who has been on hand to witness a terrain-altering meteorological event. But from the earliest, less intimate entries, we feel that we've broken the lock on the little book . . . Over the sixteen years this volume of her journals covers, Sontag grows up. Along the way she enters (at scarcely sixteen) the University of California at Berkeley and the following year transfers with a scholarship to the University of Chicago where she meets and marries Philip Rieff . . . Among the entries are also lists of books to be read and words to be learned contemplated, lists of things to be done and things not to be done, mentions of areas of history to become acquainted with, the odd aperçum general reflections, and whole meadows of quotations. We see rudiments of ideas which years later expand into essays, and we see aspects of the author—and the author's view of herself—that there certainly would be no other way to see. Though descriptions of the outside world do turn up, Sontag's forceful attention is largely reflexive . . . We have been dared to read. Sontag did not destroy her journals nor did she restrict them."—Deborah Eisenberg, The New York Review of Books

"Reborn, as Rieff has titled the book, is what Sontag says she felt when, at 16 and a freshman at UC Berkeley, she entered into her first sexual relationship with a young woman. Sex is the theme of this volume, showing the way it illuminates life for a brilliant young thinker who is uncomfortable in her flesh and how it becomes a measure for her thereafter of personal and artistic freedom."—Laurie Stone, Los Angeles Times

"By the time she died four years ago, Susan Sontag had been for decades a kind of intellectual plenipotentiary, novelist, culture critic and that most unlikely of all job categories, famous essayist. In person, Sontag could be warm, patient and funny. On the page, she was omniscient and intimidating, somebody who had read everything and assumed you had too. Where, you wondered, did she find the time? Now we know: she got an early start. Reborn: Journals & Notebooks, 1947-1963, the first of three projected volumes selected from the diaries Sontag kept nearly all her life, is a portrait of the artist as a young omnivore, an earnest, tirelessly self-inspecting thinker fashioning herself into the phenomenon she will be . . . Her journal is her true first book, the story of a woman struggling with her consciousness."—Richard Lacayo, Time

"By the end of her life in 2004, the novelist and essayist Susan Sontag had turned the most persistent critique of her talent — that her greatest creation was her own daunting persona—to a point of pride. 'Good for her! More power to her,' she said about Emma Hamilton, the rags-to-riches heroine of her 1992 novel, The Volcano Lover. 'I love self-made people.' Sontag was one herself. Born Susan Rosenblatt and raised in Tucson, Ariz., and North Hollywood, she had, by age 30, catapulted herself to the center of America's literary establishment. With the just-published Reborn, the first installment of Sontag's journals—edited by her son, David Rieff—we now have the absorbing story of the inner evolution that made that journey possible. The strong-willed voice was there from the beginning. In her very first journal entry, the then 14-year-old writer declares there is no afterlife. Among her other beliefs: 'that an ideal state . . . should be a strong centralized one with government control of public utilities, banks, mines + transportation.' Her seriousness does not let up. Reborn is full of earnest exhortations to read books (Moll Flanders, another tale of self-creation) and smile less ('Think of Blake. He didn't smile for others'), as well as descriptions of lectures attended and films inhaled, sometimes at the rate of three a day. Were Reborn merely a diary of such intellectual conquests, it would grow tedious, even to fans. But in passages chronicling the experiences that gouged her, the self-consciousness that dogged her, the marriage that nearly smothered her and the self-discoveries that redefined her, the famously fierce Sontag retreats to a sometimes humble, sometimes confused tone that is a revelation. As the journals progress, Sontag's thoughts on love and sexuality and the car-wreck relationships she had with women push from the page her earnest list-making of books to read. It's as if the poles of the private life and the life of the mind are bending toward each other. Finally, on the book's last page, they touch in a sentence fragment: 'Intellectual "wanting" like sexual wanting.' As do all the best critics, Sontag gave us new metaphors for how to read and see. Fabulously, surprisingly, Reborn shows she used that skill to understand her own pell-mell life."—John Freeman, NPR

"With the publication of Reborn—selections from the entries Sontag wrote between the ages of 14 and 30—we can now track the agonizing process of that self-creation: the first steps in her journey from a suburban California loner to America's reigning public intellectual . . . The most thrilling stretch of Reborn is its beginning, where we get a sustained look at a heretofore entirely mythical creature: the teenage Susan Sontag . . . She is, against all odds, a deeply lovable character. Her comically oversize ambition grew out of an equally oversize pain."—Sam Anderson, New York magazine

"I first read Susan Sontag's 'Notes on "Camp"' in college. I proceeded slowly and with minimal comprehension, took careful notes and imagined the owner of that stern, abstruse voice living in a faraway land of brilliance, black sweaters and espresso. In New York, or Paris somewhere, smoking with Roland Barthes, Michelangelo Antonioni and Jackson Pollock. Sontag was not real. Not until the morning about four years later when one of my coworkers at PEN American Center was instructed to 'call Susan' to ask her something or another, and upon placing the call was soundly lambasted by Ms. Sontag herself. Everyone with half a brain cell knew, apparently, not to call a writer before two in the afternoon. For the next ten years, I had what seemed like regular encounters with the enigma. I witnessed the tussles between PEN and an unauthorized biographer over access to her PEN files; pored over a box of endearingly neurotic correspondence in the archives of her publisher Farrar Straus and Giroux at the New York Public Library; spotted her and Annie Leibovitz at a Strindberg play at BAM, soon after a bout with breast cancer. By the time Sontag died in 2004, she had become human. But not entirely comprehensible, and never simple. She might in fact be one of the most elliptical writers to have crossed over into mainstream American cultural criticism. Her essays are dense hedges of precisely constructed ideas, cloaked in rhetorical assault and accessorized by brilliantly aphoristic quotes. Remarkably, Sontag's notebooks, out this month in a first volume, Reborn, covering the years 1947–1963, aren't all that different from her other published work—at least in temperament. 'Ideas disturb the levelness of life' is the leadoff entry to her 15th year. 'Life lives on,' she writes, quoting herself quoting Lucretius at 16, 'it is the lives, the lives, the lives that die.' Ten years later, a crib note on the philosophy of Max Scheler is followed by the pronouncement: 'In marriage, every desire becomes a decision.' Sontag expressed herself in crystals, even when dredging the murk of adolescence, sexuality, ambition, divorce, motherhood and love . . . The journals are stocked with lists of books to read (Scholem! Gide! Flaubert!), movies seen (so many) and philosophical précis. Despite the fact that a book list from an 18-year-old Susan Sontag is a literary log of the highest level, these sections are essentially little intrusions to the latticework biography emerging from the candor of a woman who lived in a huge, lustful, deep way, yet always also in her mind."—Minna Proctor, Time Out New York

"The publication this month of the first volume of Susan Sontag's Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963, edited by her son, David Rieff, is a significant event in the literary world. The book gives us more fully than ever the mind and sensibility of one of the 20th century's finest writers at work during her formative years. It provides compelling insights into the world (and underworlds) that she successively inhabited: Berkeley, Calif., in 1949; Chicago from 1949 to 1951; Cambridge, Mass., in the mid-1950s; Paris in 1958; and Manhattan as of 1959. The New York Times published brief selections from Sontag's journals two years ago, bringing to the public some of what is in the extensive collection of her unpublished writings, now open at the Charles E. Young Research Library at the University of California at Los Angeles. But the new book opens up a much wider range of issues than appeared in the Times selections: Sontag's sexuality; the world of gay, lesbian, transgendered, and transsexual people (although she does not use all those words) from the late 1940s into the early 1960s; the nature of her life with Philip Rieff during their troubled marriage, which began in 1950 and ended in 1958; her interest in Jewish history and religion (more apparent in the journals than in her writings for much of her career); her relationship to her mother and to her son; her ambitions and self-fashioning; and, above all, the origins and development of her movement from modernism to something akin to postmodernism . . . With its frank discussion of Sontag's sexual experiences and knowledge, Reborn will therefore fascinate many readers (although one hopes they will also see the connections between her most intimate experiences and her writings) . . . The journal entries offer compelling evidence of what Sontag was thinking and experiencing. David Rieff reflects that it is impossible to imagine his mother returning 'to her social and ethnic context for inspiration, as many Jewish-American writers of her generation would do.' Yet Reborn does make clear how often she pondered questions about Jews and Judaism. She noted how patriarchal Jews were; worked to learn the difference between death camps and concentrations camps; and remarked in 1957 that 'I am proud of being Jewish'—before adding, 'Of what?' Readers will also learn from Reborn a great deal about the world of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people and the transgendered in the late 1940s in the Bay Area . . . Sontag's keen observational power and brilliant writing takes us on a tour of gay San Francisco, providing descriptions of all sorts of gender bending as well as of the style and sexual practices of gay men and lesbians . . . What Reborn reveals are the sources of Sontag's transformation into a powerful writer and major celebrity. The connection she articulated in 1949 between lesbianism and passion was central to her long-gestating articulation of an aesthetics that includes sexuality and sensuous pleasure. Although she pursued a Ph.D. and taught at colleges and universities, she connected sensuality with a rejection of what she saw as the stuffy constrictions of academic life. Her passionate beliefs all but assured that she would pursue a career as a writer outside academe . . . [Sontag] has left us with a rich legacy—her books and essays and now, thankfully, this first installment of her journals and notebooks."—Daniel Horowitz, The Chronicle of Higher Education

"Activist, philosopher, writer and thinker Susan Sontag died in 2004 0f cancer but her legacy lives. With Reborn: Journals & Notebooks 1947-1963, the first of what will eventually be three volumes of her journals, Sontag fans can dig deeper into what made her a unique and compelling figure in the world of American intelligentsia. This collection gives us a glimpse of Sontag's earliest years, from her first tries as a writer of fiction to her recollections of coming of artistic age amid the hurly-burly of New York City in the early '60s. Reborn is made all the more powerful by the preface from her son, David Rieff. But what the reader takes away mostly is the force of Sontag's personality."—Cary Darling, Star-Telegram

"Even as a teenager she as avid for life, literature, art, music; she was also self-doubting and desperate for approval. She saw romantic love as 'giving yourself to be flayed and knowing that at any moment the other person may just walk off with your skin.' Now, four years after Susan Sontag's death, her son, David Rieff, has made the difficult decision to expose the private passions of this American cultural icon by publishing the first of three projected volumes, Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963, an evolutionary history of an insatiable mind."—O, The Oprah Magazine

"In September 2006, two years after Susan Sontag's death at 71 from blood cancer, The New York Times Magazine published excerpts from her notebooks: unfettered jottings on books, dates, people—but mostly her sense of self—by the writer and public intellectual with the iconic white hair streak. The rippling thrill that this unearthed material had on a certain pop culture-addicted, humanities-majoring, I-will-read-Hegel-someday demographic was as great as if one verifiable fact about TomKat or Brangelina had been unveiled—maybe even greater. The link sailed through the Monday-morning e-mail channels: Did you see? Did you read? What did you think? We wanted more. The more, at least the beginning of the more, is here. Reborn: Journals & Notebooks, 1947–1963 is, as Sontag's son, the foreign affairs journalist David Rieff, explains in his preface, the first of three volumes to be culled from her walk-in closet's notebook stash. (No wonder she never mentions clothes—where would she have put them?) Rieff's rage at feeling forced to publish these highly personal documents, because his mother sold her papers to UCLA without instructions, simmers beneath the surface of his comments. But why bother worrying whether it was right to bring these to light? The fruits of Rieff's editing labors are a gift, a page-turning joy—it couldn't have been easy for him to stumble on passages such as 'P. [Philip Rieff, his father] and I used to talk often about using double contraception + starting to have sex again.' The first installment reads like the best books should: There's a compelling plot—we watch aghast as, at 16 and on the verge of a lesbian awakening, Sontag falls without explanation into a stifling marriage to Rieff, a sociologist whose class she audited; then we tremble as she wrestles herself out, damaged child and husband be damned, and discovers orgasms. Is she a bit of a coldhearted bitch? Yes, but aren't we all when it's a matter of survival? She's also funny. Her compulsive literature and cinema lists are a highbrow High Fidelity, and her arch self-awareness will make you laugh aloud. "How easy it would be to convince myself of the plausibility of my parents' life!" she writes in 1948—an absurdly precocious 15-year-old en route to UC Berkeley, but a teenager nonetheless. Or this, on a trip after a breakup: 'Stunned + sleepy ever since I'm here . . . The "real me," the lifeless one . . . The slug. The one that sleeps and when awake is continually hungry. The one that doesn't like to bathe or swim and can't dance. The one that goes to the movies. That one that bites her nails. Call her Sue.' Even for those who never quite got to her seminal works—'Notes on "Camp,"' say, or On Photography—or her discordant, unexpectedly memorable fiction (The Volcano Lover), Sontag holds a particular fascination in this age of self-branding. She invented the ultimate freelancer's role, a one-woman business in the culture industry, never stooping to suck up to a corporation or institution. These notebooks might lead detractors to accuse Sontag, yet again, of an unseemly will to power, a fixation on fashioning her persona; they'd do better to take her musings at face value. Anyone struggling with how to live without compromise or shame, how to produce art, to raise a child, to have good sex, will find validation in Sontag's brilliantly articulated but recognizable impasses. 'Work = being in the world,' Sontag writes, in a typical construction whose far-reaching implications belie its economy. Few worked at it harder, and how lucky for us to have a blueprint from a heroine who got it so right."—Miranda Purves, Elle

"If anyone is under the impression that Susan Sontag was, beneath her intellectual brio, just like everyone else, a quick perusal of Reborn: Journals & Notebooks 1947-1963, edited by her son, David Rieff, should put that idea to rest. The extraordinary notebooks begin when she is a teenager, heading off to Berkeley, and carry her through her unhappy marriage to Philip Rieff, to Oxford and Paris, and, finally, back to New York. The diaries are shocking, singular, in both the intimacy of their brisk, notelike form and the astonishing personality they reveal . . . The journals are largely comprised of lists, ways to improve herself, books she should read, chronologies. They give evidence of a fierce and unrelenting campaign to work on herself as an intellectual, as a woman, as a mother. 'In the journal,' she writes, 'I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself.' She was 24 years old. What is remarkable here is the ferocious will, the conscious and almost unnatural assembly of a persona that rises above and beyond that of ordinary people. The determination she devotes to figuring out who to be, on the most basic and most sophisticated levels, is breathtaking . . . The Sontag in these diaries is mesmerizing, brilliant, abrasive, not quite likeable. Rieff mentions that he has not edited extensively and that she never read her journals out loud or intended for other people to read them. This appears to be true. They feel raw, unprocessed, like scribbled notes to herself, which gives them a greater power and immediacy than other, more polished diaries and memoirs that seem to anticipate and cater to their public. They were meant for her, and she did not write and move on: Sontag comments in the margins later, like a professor weighing in judgment, on a former self, never leaving herself alone. There is in an important way no difference between her own experience and a particularly absorbing book she might be reading. One can't help but admire the intricate mental apparatus at work: She is writing notes on her notes. These private jottings are, like her famous essays, almost entirely abstract and cerebral: She almost never describes the physical world, what the sky looked like, the smell of orange trees in Seville, or what she and her lover ate for breakfast . . . If there was any doubt, the notebooks confirm that the uncompromising intelligence, the unsparing honesty Sontag shows in her work is not a pose or affectation. Her entries give evidence that she is to her core as unrelenting, unironic a critic in life as she is in her work. The harshness and purity and impossibility of her writing carry through into her days. All the weakness she fears in herself, the baroque and excessive self-contempt she feels, is marshaled for the highest cause: She wills herself into a strength of vision and ambition of voice unrivalled in a woman thinker. She writes, '[T]he writer is in love with himself,' and so she labors to create a self she can love, to reflect that perfect, arrogant writer's confidence, that necessary narcissism. In his rather beautiful and tormented introduction, Rieff wonders whether he should have published these journals at all, as his mother never made her wishes clear before she died. But the reader, at least, is grateful that he did. The notebooks are invaluable for anyone interested in how the serious and flamboyant intellectual dreamed up her greatest project: herself."—Katie Roiphe, Slate

"Rieff sensitively portrayed revered critic and novelist Sontag during her last days in Swimming in a Sea of Death (2008) and now continues to navigate the great sea of her legacy as editor of her journals. He didn't want to open his mother's private life to public eyes, but because her papers are available to scholars, he does so preemptively, granting readers access to the innermost thoughts of a genuine prodigy. In 1948, at age 15, Sontag asks, 'And what is it to be young in years and suddenly awakened to the anguish, the urgency of life?' After starting college at 16, she fills her journals with passionate analysis of books, her intellectual ambitions, her struggle to accept her homosexuality, and the ecstasy and torment of her first lesbian relationship. Then, suddenly, this ardent seeker becomes a wife and mother. She loves her son, but marriage does not suit her, and her battle to reclaim her true self is one of several dramatic rebirths punctuating this electrifying record of Sontag striving to become Sontag."—Donna Seaman, Booklist

"The first of three planned volumes of Sontag's private journals, this book is extraordinary for all the reasons we would expect from Sontags writing—extreme seriousness, stunning authority, intolerance toward mediocrity; Sontags vulnerability throughout will also utterly surprise the late critic and novelists fans and detractors. At 15, when these journals began, Sontag already displayed her ferocious intellect and hunger for experience and culture, though what is most remarkable here is watching Sontag grow into one of the century's leading minds. In these carefully selected excerpts (many passages are only a few lines), Sontag details her developing thoughts, her voluminous reading and daily movie-going, her life as a teenage college student at Berkeley discovering her sexuality (bisexuality as the expression of fullness of an individual), and meeting and marrying her professor Philip Rieff, with whom, at the age of 18, she had David, her only child. Most powerful are the entries corresponding to her years in England and Europe, when, apart from Philip and their son, the marriage broke down and Sontag entered intense lesbian relationships that would compel her to rethink her notions of sex, love (physical beauty is enormously, almost morbidly, important to me) and daughter-and-motherhood, and all before the age of 30. Watching Sontag become herself is nothing short of cathartic."—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

BOOK EXCERPTS

Read an Excerpt

REBORN

1947

11/23/47

I believe:

(a)That there is no personal god or life after death

(b)That the most desirable thing in the world is freedom to be true to oneself, i.e., Honesty

(c)That the only difference...