Chapter One

1927

They say it is rare to have good reason to leave Berlin. In the summer you have Wannsee, where the beaches are powdered and cool, and where for a few pfennigs even a clerk and his girl can manage a cabana for the day. The cold months bring the Ice Palast up near the Oranienburger Gate, or a quick trip out to Luna Park for the rides and amusements, where a bit of cocoa and schnapps can keep a family warm for the duration. And always there is that thickness of life in the east, where whiskey (if you're lucky) and flesh (if not too old) play back and forth in a careless game of half-conscious decay. No reason, then, to leave the city with so much to keep a hand occupied.

And yet she was empty—not truly empty, of course, but thin to the point of concern. A phenomenon had descended on Berlin in early February, something no one could control or predict. Naturally they could explain it, but only in the language of high science and complexity. For the rest, it was simply Weisserhimmel—white sky—days on end of a too-bright sun without the sense to generate a trace of heat. Every forty years or so, it ca as a faint reminder of the city's Nordic past, but history was not what Berliners chose to see. They were unnerved, their world made too clear, and so they left: businesses took unexpected holidays, schools indefinite recesses. It would all pass in a few days' time, but in the meanwhile, only the stalwarts were keeping the city alive.

Still, a few hours on the outskirts of town could do wonders. The sun might have been no less forgiving, but at least the surroundings were unfamiliar for a reason. Nonetheless, Nikolai Hoffner continued to glance into his rearview mirror as he drove. The Berlin he saw seemed compressed, small, her reflection strangely misleading. Even distance was doing little to help. He knew it best not to stare.

Instead, he opened his mouth wide and chanced a look at his teeth; they seemed to shake with the car's motion. The tooth, he had been told, would have to come out. Funny, but it didn't look all that different from the others, a bit thick, crooked, yellowed by tobacco. Hoffner had little faith in doctors, but he believed in pain, and that was enough. He was meant to rub some sort of ointment on his gums every few hours, at least until he could make time for an appointment. He was finding a brandy worked just as well.

The road to Neubabelsberg—the new road to Neubabelsberg—was straight and smooth, and for the price of a few pfennigs had you out to the film studios in less than half an hour. Someone had had the brilliant idea that Berlin needed a racing circuit, an asphalt totem to Mercedes and Daimler and Cadillac—although no one spoke of Cadillac—that ripped through the satiny pine needles and heavenly green leaves of the Grunwald. There had always been something of an escape when it came to the woods and lakes and beaches of the great, untamed forest. Now even that was gone, or going, eighteen kilometers uninterrupted. It seemed to dull everything.

With a quick press of the accelerator, Hoffner decided to test the old car. The exhaust roared and a hum rose as the rubber tires heated on the road. That was always the trick: to smell when they had reached their limit. These had the tang of disarmament surplus, the good military stuff that appeared now and then from some unknown warehouse. Everyone knew not to ask.

A big Buick hooted angrily from behind, and Hoffner checked his mirror again: the car had come from nowhere. He waved the driver on and watched as first the radiator, then the cabin, raced by. The Kriminalpolizei had yet to invest in speed. It would take something else to catch the criminals.

There was a sudden thud to his undercarriage—a parting gift from the Buick—and Hoffner waited for the agonizing scrape of metal on asphalt, but none came. Still, there might have been a puncture, or something wedged in where it wasn't meant to be. Not that Hoffner knew anything about a car's tending-to, but he reckoned he should take a look. After all, he would need a bit of grease on his face and hands to show at least some effort to the boy they would be sending out to tow him.

He brought the car down onto the grass and reached over for the two yellow flags he kept in the glove compartment. It was a pointless exercise—six meters in front, six meters behind—but someone had taken great pains to devise die Verkehrsnotverfahren (emergency traffic procedures), the totality of which filled a full eight pages in the bureau's slender handbook on automobile operation: Who was he to question their essentialness? The flags blew aimless warning to the deserted road as Hoffner lay on his back and pulled himself under.

Surprisingly, everything looked to be in working order. Various metal shafts stretched across at odd angles. Metal boxes to hold other metal things were bolted to iron casings, and while there were two or three wires hanging down from their protective covers—each wrapped in some sort of black adhesive—nothing appeared to be torn or strained or even mildly put out. The wood above was worn but whole, and the tires looked somehow thicker from this vantage point. Hoffner imagined much the same might have been said of his own fifty-three-year-old frame: shoulders still wide even if the barrel chest was relocating south with ever-increasing speed. He caught sight of a line of blurred handwriting on one of the tires and slowly inched his way over. Closer in, the scrawl became Frankreich, Süd, 26117-7-6, Vichy.

Hoffner smiled. These had been slated for reparations, not surplus, and yet somehow—just somehow—they had failed to make it across the border. In fact, very little these days was making it to the French or English or Belgians or Italians—how the Italians had managed to get in on the spoils, having sided with the Kaiser up through 1915, still puzzled him—except, of course, for the great waves of money. There, things were decidedly different. The French might have been willing to turn a blind eye to a few tires ending up in the service of Berlin's police corps, but if so much as a single pfennig of repayments, or interest on repayments, or interest on the loans taken out to pay for the interest on those repayments went missing, then came the cries from Paris for the occupation of the Rhine and beyond. It was a constant plea in the papers from the ever-teetering Social Democrats to keep our new allies happy, keep the payments flowing out, no matter how many times the mark had to be revalued or devalued or carted around like so many reams of waste tissue just to pay for a bit of bread. Luckily, the worst of it was behind them now, or so said those same papers: who cared if Versailles and its treaty were beginning to prompt some rather unpleasant responses from points far right? Odd, but Hoffner had always thought Vichy in the north.

He slid out, planted himself on the running board, and flipped open his flask. The Hungarians, thank God, had remained loyal to the Kaiser up to the bitter end: little chance, then, of a shortage on slivovitz anytime soon. He took a swig of the brandy and stared out into the green wood as a familiar burning settled in at the back of his throat. A trio of wild boar was digging up the ground no more than twenty meters off. They were a dark brown, and their haunches looked fat and muscular. These had done well to keep the meat on during the winter. The smallest turned and cocked its head as it stared back. No hint of fear, it stood unwavering. Clearly, it knew it was notits place to cede ground. Hoffner marveled at the misguided certainty.

He tossed back a second drink just as a goose-squawk horn rang out from the road. Hoffner turned to see a prewar delivery truck pulling up, its open back packed with small glass canisters, each filled with some sort of blue liquid. Hoffner wondered if perhaps he might have failed to hear about an imminent hair tonic shortage, but the man who stepped from the cab quickly put all such concerns to rest. He was perfectly bald, with a few stray wisps of black matted down above the ears. Hoffner stood as he approached.

" 'Twenty-two Opel?" The man spoke with an easy authority. "They'll give you a bit of trouble on a road like this."

Hoffner nodded, although he couldn't remember whether the car was a '21 or a '22. "I thought I'd caught something underneath," he said. "Didn't see anything."

"High frame," said the man. "Not meant for these speeds."

"You know your cars, then?"

"I take an interest. So nothing up in the housing?"

Hoffner motioned to the car. "You're welcome to take a look."

The man stepped over, released the catch on the metal bonnet, and raised it. "You keep it well." He leaned in and jiggled a few bits and pieces.

"Yes," said Hoffner, never having once opened the thing up himself. He noticed the baby boar still watching them. "Cigarette?"

The man stood upright and refastened the bonnet. "Very kind."

"I'm the one who should be thanking you."

"For what? Your car is in perfect order." They both lit up and leaned back against the bonnet. "Unless it's for the company?" Hoffner held out the flask. "No," said the man. "I'm not much good with that."

Hoffner nodded over to the truck. "You've an interesting load."

"Toilet-washing liquid," said the man. "Very glamorous. I'm heading out to the studios. Same as you." It was an obvious point: Who else would be taking this road? "I shouldn't, of course. Slows everyone down, but then, why not? I choose my times well enough. Eleven on a Monday. Very little traffic either way. If you'd really been unlucky, you'd have been here for quite some time."

"Depends on what you mean by luck."

The man smiled absently. "Fair enough."

"And here I thought the studios would have had—"

"A bigger outfit running their toilet-washing-liquid interests?" The man had evidently run through this before. There was an odd charm to it all. "Of course, but then I'm an inside man. I was owed. Favors and so forth. Highly confidential stuff."

"The intricate world of toilet-liquid syndicates."

"Exactly." The man nodded over at the boars. "They'll make someone a nice bit of eating."

"That would be a shame."

"You don't like eating?"

Hoffner took a pull on his cigarette. "So how does one become an 'inside man'?"

"The usual course. A producer, director—I don't remember which—one of them had an eye for my daughter. Got me the contract. On a limited basis, of course. One man, one truck. Enough liquid for the small buildings. More if she spread her legs."

"Imagine if she marries him?"

"I don't. She ran off to Darmstadt with a butcher's apprentice two years ago. I think the studio felt sorry. Old widower abandoned by his only daughter."

"That's a bit rough."

"Not really. They let me keep the contract. Don't know why. I never liked her much. She's probably fat now. Fat like that big one there. With a child. A fat little boy. He probably beats her. The butcher, not the child."

Here it was, thought Hoffner. The man had lived through the Kaiser, the war, unemployment, a daughter, and none of it mattered, not so much at its heart as in its passing. Berlin's saving grace had always been her incessant movement forward. Only a real Berliner understood that.

"Quite a sky," said the man. Even the briefest of conversations had to make mention of it. "It'll pass."

"I imagine it will."

The man took a last pull, then flicked his cigarette to the ground. "Bit early for a cop to be heading out to the studios."

All this certainty in the Grunwald this morning, thought Hoffner. "Highly confidential stuff."

The man exhaled as he pushed himself up. "Yah. I'm sure it is." Inside the cab, he leaned out the window. "Watch where you piss out there. Make my life a little easier." He put the truck in gear and headed off.

Hoffner crushed out his cigarette and noticed all three of the boars now looking back. For some reason, he bent over and picked up the man's cigarette; it was still moist. He then opened the door, tossed the butts onto the passenger-side floor, and pressed the starter. The sound sent the boars darting into the wood, and Hoffner turned to see them disappear. This they were afraid of.

Settling in, he pulled the door shut and headed up onto the road.

THE FIRST OF THE STUDIO buildings emerged on the horizon like a caravan of turtles. The film men had bought the land before the war, an abandoned factory stuck out in the middle of nowhere. Safer that way, they reasoned: no apartment complexes nearby to go up in flames should the reels catch fire. The place had grown in the intervening years. Under a vacant sky, the sprawl seemed even more desolate.

Hoffner pulled up to the gate and waited, a walled fence stretching off in either direction. The Ufa emblem dangled precariously above. To the side, a large billboard advertised the most recent studio triumphs: posters of Emil Jannings and Asta Nielsen, Conrad Veidt in some menacing pose, along with the warnings APPALLING! DANGEROUS! DAUGHTERS BEWARE! Veidt's shadow was especially well placed—obscuring the crucial E and W in beware!—and informing the casual reader that, perhaps, the daughters might be nude in this particular film. Hoffner appreciated the designer's ingenuity.

He reached for his badge as the guard approached.

"No need for that, Herr Kriminal-Oberkommissar." The man's easy grin seemed at odds with the long coat, braiding at the shoulders, and equally impressive hat. He might have been a doorman at the Adlon or Esplanade if not for the Ufa logo on his lapel. "Bauer," he continued. "Oberwachtmeister Anders Bauer, retired. I was at the Alex with you, last posting before my thirty-five came up."

"Bauer." Hoffner nodded as if he recalled the man. "Of course." It was nothing new for an old Schutzi sergeant to find himself a night watchman or gatekeeper around town, especially when everyone's pension had blown up with the inflation. Why not out at the film studios: more exotic, Hoffner imagined. "You've landed yourself a nice bit of work."

"Can't complain, Herr Kriminal-Oberkommissar." He handed Hoffner a yellow card that read "Day Pass—Grosse Halle." "Hot meals at the commissary. Good uniform." Bauer's expression hardened. "Naturally you've come about that business with Thyssen, Herr Kriminal-Oberkommissar." He brought a clipboard up and pointed to where Hoffner was meant to sign.

Hoffner enjoyed the dedication: it was still in the old dog's blood. "Business," he said as he scrawled his name. "I was told suicide."

"You hear things, Herr Kriminal-Oberkommissar. That's all." Bauer gave an unconvinced nod. "But if they say suicide, then it must be suicide."

Hoffner placed the card in his coat pocket. "Well then, you hear anything else, you let me know. Just between the two of us—Herr Oberwachtmeister."

The man's eyes flashed momentarily. "Absolutely, Herr Kriminal-Oberkommissar." And with a sudden Teutonic precision, Bauer returned to the gate, pulled up the barrier, and motioned Hoffner through. Not wanting to spoil the man's performance, Hoffner took the car in without the slightest idea where he was going.

AS IT TURNED OUT, every road seemed to lead to the Grosse Halle. Hoffner followed the signs past a series of bungalows and out into an open area where a stone wall with turrets rose in the distance. At its side, a dragon's head peeked out from behind a bush. For anyone who had stepped inside a movie palace in the last two years, this would have been exhilarating: images meant to be seen only in flickering light now made real, if perhaps less epic. Hoffner's son Georgi had explained it all to him, angles and lenses and lighting, but what was the point in knowing when it reduced it to this? Even so, Hoffner barely noticed them as he turned down a narrow lane, past a row of flat, soulless buildings and up toward the Great Studio.

The papers had been full of it last year when the massive thing had gone up, this many meters long, that many meters wide, "as tall as ten men to the catwalks!" and with an entire wall made of glass for natural light. Had the sky shown even the slightest hint of color there might have been something ominous in its stare. Instead, the place simply looked brown.

A young man in a bow tie and plain shirt was waiting in front of a line of entrance doors. He was conspicuous for his lack of movement among the others of his breed, darting about with their clipboards and papers and tidy vitality. The boy began to jog over the moment he saw Hoffner pull in between two Daimlers.

"Herr Chief Inspector," he said. Hoffner stepped out of the car. "Eggermann, Rudi Eggermann. Everyone calls me Rudi." The boy had been trained on how to present himself. "We have the Herr Direktor waiting upstairs for you."

Hoffner's suit drew several glances as he and the boy made their way up toward the main entrance. Stylish for 1923, it seemed to match the color of the brick.

"Very impressive," Hoffner said as he peered up at the building and its myriad doors. He pulled a cigarette from his pocket.

"Yes. Thank you, Herr Chief Inspector."

Hoffner nodded vaguely in the direction of the doors as he lit up. "How do you know which one?"

Confusion cut across the boy's face. "Which one what, Herr ChiefInspector?"

"Which one to use. The doors. Where they go."

"Oh." The boy nodded eagerly. "How do we know. Of course. Actually, it's not all that difficult—"

"I'm joking with you, Herr Rudi." Hoffner let out a long stream of smoke. "You managed to pick me out among the Mercedes and Daimlers. I'm assuming you know your way around."

Inside, the foyer housed a small office, a row of telephone booths, and a single wide corridor that led deeper into the building. Halfway down the hall, the boy was forced to slow for a train of women who looked as if they had each come second to the winner of a Marie Antoinette dress-up contest. Each held a fashion magazine or cheap little novel in her grasp as they all shuttled down the hall and into a large room where an entire legion of French aristocrats were either sitting or reading or dozing. A dice game among a few comtes and peasants had drawn a crowd in a corner. Nice to see the Weimar democratic spirit alive and well, thought Hoffner.

He followed the boy into a waiting elevator, and they headed up.

THE PENTHOUSE FLOOR was an open-air atrium, with a carpeted balcony that extended around all four sides in pristine white. Hoffner peered over the edge to the little chessboard of activity eight stories down as he followed the boy past the offices and dressing suites reserved for Ufa's executives and major stars.

The design was really quite ingenious, the whole thing subdivided by movable bricked-in walls so that the big films and little ones could all be shot at the same time. Great sand deserts butted up against French palaces, a section of Friedrichstrasse seemed to end on a mountaintop, and the most curious was a casino that looked on the verge of an elephant stampede. Hovering above it all were the tall cranes with cameras and lights attached, distant figures perched on poles or hanging from wires. The rising chatter would have been deafening if not for the glass dome that extended across the atrium from the floor below. Up in the heavens, however, all was serene. Hoffner wondered if the designers realized how clever they had been to choose Babelsberg for their tower.

"My younger boy is very interested in all of this," Hoffner said as he continued to gaze over.

"It's an exciting industry, Herr Chief Inspector." Hoffner wondered if young Rudi carried the brochure with him at all times. "May I ask how old?"

"Third year, Friedrichs-Werdersches Gymnasium." A great torrent of water was now making its way down the mountain. "A fencer. Sixteen."

"You should have him get in touch with us. We could find something for him—running scripts, filing film. On the weekends, of course."

"No," Hoffner said easily as he watched the water disappear as quickly as it had come. "This isn't the sort of place for a boy of sixteen."

There was an awkward nod before Rudi motioned to the corner office. "Here we are," he said, rather too relieved.

Hoffner looked up to see a heavyset man standing outside the door. His suit was a recent purchase, though he had yet to learn how to wear it. The man nodded with an unwarranted familiarity as Hoffner approached.

"Hoffner, Kern," Kern said, ignoring Rudi entirely. "You're free to do whatever it is you do, Eggermann. We'll be taking it from here."

Hoffner waited a moment, then turned to his young guide. "You've been very kind, Herr Rudi. Please inform your studio security man I won't be needing him." And without so much as a nod, Hoffner took hold of the handle and started in.

Kern's thick hand quickly held the door in place. "What the hell do you think you're doing, Kripo?"

Again Hoffner waited before turning. "Well, I could waste my time on your notebook full of scribblings or your ideas about when and how all this happened. Or you could tell me how you chose to make private security your calling, the freedom and glamour and so forth, when we both know there are three, more likely four, failed Kripo entrance examinations in your not-too-distinguished past. I was hoping to save you all of that in front of Herr Rudi here, but it seems that's not meant to be. My guess is that the two or three very powerful men inside this office are waiting to tell me just exactly what they think I need to know without any help from you. So thank you for standing guard until I arrived, but I think we're done." Hoffner pointed to Kern's shirt. "And you might want to take care of that. Jam tart can leave a stain."

Hoffner knew it was poor form to enjoy the look on Kern's face as much as he did, but then they had brought him all the way out here on a Monday morning for what was probably nothing more than another aimless tryst gone wrong, all of which would be conveniently brushed aside by some well-placed cash or favors for men too far above him at the Alex for any of it to trickle down his way. He would still have to go through the paperwork for the extra petrol allotment when he got back. Kern seemed the appropriate repository for such frustrations.

Kern, his suit even more apish, continued to hold the door: it was impressive to see that much rage contained. He seemed on the verge of saying something, when instead, he took a quick, defiant glance at Eggermann and then headed down the hall. Loud enough for Hoffner to hear, he muttered "Ass," then disappeared through the stairwelldoor.

Hoffner had hoped to see a bit of victory in Rudi's face, but the boy simply stared uncomfortably. He was out of his depth. Shame. Evidently out here they were trained to cede ground. Hoffner nodded again and stepped inside the office.

He found himself in a quite lovely and quite empty anteroom: sofa, two chairs, and a secretary's desk with a large Ufa emblem embla zoned on the front. Everything was bright, too bright, from the pale yellow color of the walls, to the beige carpet, to the white satin pillows lazing along the armrests. Jannings and Nielsen once again dominated the walls, while various film magazines stretched across a low Chinoise coffee table. The final touch was a potted palm tree in the corner. Hoffner wondered if it was possible to appear more ludicrous: there was a desperation to it that cried out, "Look at us, America! We make films, too!"

He stepped over to a second door, knocked, and pushed through.

The larger office, by contrast, was stark to the point of sterility. A long, flat desk stared out from the one corner that seemed to defy the light streaming in from the wall-to-wall window. A designer's metal chair stood sentry behind. The only nods to comfort were two low, overstuffed chairs in front of the window, but then they were denied the remarkable view of the Grunwald and beyond. One man stood staring out. Another sat in one of the chairs. The third, and oldest, was making his way across to Hoffner.

"Ah, Herr Chief Inspector. Hoffner, is it?" He extended his hand. He was in a perfectly cut gray suit. "You've dispensed with Herr Kern, I see. My congratulations."

This was the new affectation. Weimar had brought democracy and prosperity and nude dancing and cocaine and the handshake. The clipped nod was a thing of the past. He took the man's hand. "Nikolai Hoffner. Yes, mein Herr."

"Joachim Ritter. Counsel for the studio. We finally sent Kern out. Bit of an oaf, wouldn't you say?" Hoffner said nothing. Ritter turned to the man in the chair, who was clutching a tall glass of whiskey. "This is one of our screenwriters, Paul Metzner. Still a bit shaken up. He's the one who found the body."

"I'm fine, really," Metzner said as he placed the whiskey on the desk. "Anything I can help with."

The third man now turned from the window. "And this is Herr Major Alexander Grau," Ritter continued as Grau stepped over. "The studio's director."

Grau was tall, slim, and, even without the title, undeniably Prussian. He looked much younger than Hoffner would have imagined for the head of Europe's largest studio—midforties at most—but with none of the self-conscious arrogance that comes with early success. Grau was a man certain of his place and unimpressed by his own power. In the wrong hands, it was a dangerous combination.

"Herr Chief Inspector." Grau was not a man for handshakes. He offered a clipped nod. "I can't say we have much to tell you."

"Just a few questions, then, mein Herr." Hoffner pulled a notebook from his coat pocket. "When did you find the body, Herr Metzner?"

Ritter answered: "Eight-thirty this morning. They had a meeting to discuss a script."

Hoffner asked, "And this meeting was planned well in advance?"

Ritter continued: "A day or two. It's the usual course. Thyssen was producing the film."

"He's produced several of my scripts," Metzner piped in from his chair. The glance from Ritter made it clear that Metzner had been told to sit quietly. Grau looked almost indifferent.

Hoffner jotted down a few lines to make it look official. "Was there a secretary outside when you arrived, Herr Metzner?"

"Yes," Ritter answered. "She heard and saw nothing. We have her in an office down the hall. She was feeling a bit faint."

"Anyone else?"

Ritter looked momentarily puzzled.

"Anyone else waiting in the room with her?" Hoffner clarified. "Others who would have had appointments—I'll need to speak with them as well."

"Oh, I see. Yes." Ritter glanced over at Grau, who nodded. "We can have that arranged."

"Good." Hoffner dispensed with the usual questions of pressure and lovers and gambling. Ritter would have chosen one, an offhand remark, a lowering of the eyes, poor old Thyssen; Grau would simply have looked inconvenienced by it all: it was pointless to play out the charade. Instead, Hoffner placed the notebook in his pocket and said, "So, the body, meine Herren?" Ritter began to move toward the private bathroom, but Hoffner stopped him. "If Herr Metzner could show me how he found it, mein Herr. Procedure. You understand."

"Of course." Ritter turned to Metzner. "Paul?"

Metzner stood, but Grau interrupted: "Unfortunately, I have a meeting, Herr Chief Inspector. Is there anything else you need from me?"

So much easier, thought Hoffner, when things were made this transparent: Grau was here simply to make sure Hoffner understood the hierarchy in play.

"Not at all, Herr Direktor. Thank you for your time." Hoffner extended his hand and enjoyed the slight tightening in Grau's cheeks.

Grau took it and said, "Herr Chief Inspector. Gentlemen."

He was gone by the time Metzner drew up to Hoffner's side. "I've written several murder films myself," Metzner said.

"Really?" Hoffner walked with him across the room. "And here I thought this was a suicide."

"Herr Metzner is very enthusiastic," Ritter cut in. "We pay him for his imagination."

Metzner pushed open the door to the bathroom and waited for Hoffner to move past him. Instead, Hoffner stopped. "Were any of your detectives ever the hero, Herr Metzner?"

Metzner needed a moment. "No, I don't think so."

"Then I doubt you'll be of much use to me," Hoffner said, and stepped through.

The room was almost half the size of the office, its floor in blackand-white marble, the wallpaper a deep maroon. Just in case the walk from the desk had been too taxing, there was a divan at the side of a pedestal sink, both in reach of a telephone that sat atop an iron-andglass side table. The toilet, as far as Hoffner could tell, required its own little cabin, which was at the far end and up a few steps: the image of the mysterious blue liquid fixed in his mind before Hoffner turned to the centerpiece of the room. It was a long steel massage table that stood directly across from a sunken bathtub. And it was there, in the tub, that Hoffner found Herr Thyssen.

The water had gone pinkish, with strings of deep red floating throughout. Thyssen's head was resting against a porthole window, his eyes staring out unmoving. He was young and fit, and had rough calluses at the tips of his fingers. The hand with the Browning revolver rose awkwardly over the edge; in such cases, more often than not, the recoil from the shot caused the elbow bone to snap against the porcelain. Thyssen had been lucky. His arm had flown free. The single bullet hole was just below his left nipple.

"And this is the way you found him?" Hoffner crouched down and placed two fingers on the chest: the flesh was hard, like cold rubber. The water was ice-cold.

"Exactly," said Metzner, peering over as best he could. "Nothing's been touched."

Hoffner glanced over at the towel rack. Everything was perfectly in place. He looked for a robe. There was none. "Looks standard enough," he said, even if he didn't believe a word of it. The body angle and water temperature were wrong. And the blood made no sense. There was something else, but Hoffner couldn't quite place it.

He stood and reached for a towel.

"That's all you're going to do?" said Metzner, almost disappointed.

"Is there something else you want me to do?"

"Well—you hardly touched the body."

"Oh, the body." Hoffner nodded. "You want me to look for marks or gashes or fingerprints. That sort of thing."

"Well—yes. Isn't that part of the procedure?"

Again Hoffner nodded. "I'll leave that to your film detectives." He finished with the towel. Ritter was standing in the doorway. "You said there were people for me to see. Why don't we do that."

AGAINST HIS PROTESTATIONS, Metzner was sent down to his office, while Hoffner called into the Alex for someone to come out and pick up the body.

"You're sure it's absolutely necessary?" Ritter spoke casually as the two men made their way to an office at the far side of the atrium. "You can't just let us have the family make the arrangements?"

"Standard procedure," Hoffner lied. "We need an examination, an official record." He wanted someone to take a look at the late Herr Thyssen. "The family will have him by the end of the week."

Ritter knew not to press it. "You Kripo men usually come in twos," he said.

"You've had a lot of experience with us, then, mein Herr?"

"It's a film studio, Herr Chief Inspector. There's always someone's hand to hold."

"Or pull from a tub."

"That, too."

Hoffner found the man surprisingly likable. "I had a tendency to lose mine."

"Your hands?"

My partners."

"Ah." They reached the door, and Ritter stopped. "I've started with any staff who might have had even passing contact with Thyssen in the last twenty-four hours. Script runners, copyists, that sort of thing. You understand I can't pull executives out of meetings at a moment's notice. I could set up a few interviews for you back in town. At our Potsdamer offices, tomorrow morning, say."

"That would be fine."

"Good. Not that I think any of them would have much to tell you."

"The Herr Major mentioned that, yes."

"Even so, we want the studio to be as helpful as we can. I suspect we can have all this sorted out in the next day or two. After all, suicide's no crime."

Lawyers brought pressure to bear in such delicate ways, thought Hoffner.

Ritter reached for the handle, but for some reason stopped himself. "Hoffner," he said, as if the name had suddenly taken on new meaning. He turned. "Of course. The 'chisel murders.' Grizzly stuff after the war, wasn't it?"

This was a badge Hoffner reluctantly carried. "A long time ago. Yes."

"All those women killed. And Feld, or Filder? Your young partner, always in the papers."

"Fichte," Hoffner corrected.

"That's right. You couldn't open one without seeing his face. You know, we thought about making a film. He was rather charismatic. Too gruesome, though, even for us. Might work now, though."

"It might," Hoffner said blandly.

"No doubt your Fichte's a Kriminaldirektor by now."

"No doubt."

Fichte had been dead for eight years. As had Martha. As had Sascha, all but for the dying.

It was odd to think of Sascha now, easier not to. At least the dead remained as they were, with no questions to be answered. Fichte's death had been unfortunate but no real surprise: his kind of ambition always fell prey to the corrupt. That the boy had been unable to see how deep the corruption ran at the Alex was hardly tragic, more a lesson in misguided arrogance. Hoffner's last image of him—lying on a slab, his lungs filled with poison—was enough to give Fichte's death its meaning, and why look beyond that?

For Martha there had been no hope of meaning. She had been killed for Hoffner's own arrogance—and naïveté and stupidity and recklessness—and any thought of understanding it, or seeing beyond it, was pointless. He had let them murder his wife. To ask why—to waken the dead—would have required a self-damning too exhausting to bear.

Only the very young had the resilience to sustain that kind of loathing. His son Sascha had been sixteen at the time. Hoffner hadn't seen him since.

"Winter of '20?" said Ritter.

"Nineteen," corrected Hoffner. "It was during the revolution."

"That's right." Ritter's smile returned. "Did we have a revolution? I'll have to check the film archives."

Ritter opened the door to a group of eight or nine studio employees sitting in a small anteroom. They turned as one as Hoffner stepped inside.

Ritter said, "Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. This won't take long. The chief inspector has a few questions for each of you." He turned to Hoffner. "You can take them individually through to the office. Give me a ring when you've finished. Dial 9. They'll find me."

Hoffner studied the faces, all young, all with something and nothing to hide. It would be a waste of time. There was a boy in the corner, clearly intent on the girl next to him. The Kriminalpolizei had just interrupted his best efforts. It was laced across his face.

"That one there," said Hoffner as Ritter turned to go. Hoffner was pointing to the boy. "He's not involved in this."

Ritter turned back. "And why is that?"

"Because he's my son."

LISL

THE SECOND OFFICE was no more comfortable than the first, not that Hoffner or the boy was in any mood to sit.

"What do you want me to say, Georgi?" Hoffner was onto his second cigarette. "I'm surprised. That's all."

"I thought you knew." It was a hollow answer. Georg had been doing his best to keep things light, but even he had his doubts about this last one. "Either way, it's where we are now."

Hoffner nodded once, twice. He had always liked Georg's candor. Now it just seemed grating. "You've left school, then?"

"For the time being." Georg was taller than his father. He seemed to grow taller still with this admission. "The last two months."

"And the money I've been sending you for tuition and rooms?"

"Very helpful, thank you. I share a flat with a friend just south of Friedenau."

"How artistic of you. And this friend—also a filmmaker in the making?"

"He's a writer."

"That's unfortunate." An ugly thought entered Hoffner's mind. "Your brother wouldn't have had anything to do with this, would he?" Georg's eyes grew momentarily sharper. Hoffner had never seen it in the boy before, that severity that invades the face and leaves no trace of childhood. Georg had found it at only sixteen. Hoffner crushed out his cigarette. "A stupid question. I apologize."

Georg let it pass. "I haven't spoken with Sascha in months. I'm not even sure he's in Berlin."

These were the tidbits Hoffner was allowed from time to time. He saw Georg only on weekends: Who had time for anything more? The boy's aunts were no doubt still keeping a close watch. Naturally, they had decided not to tell him about this recent gambit.

"And you make a bit of money running from office to office?" It was the best Hoffner could come up with to sound conciliatory.

"A bit. It helps to be on tuition."

"Yes, I'm sure it does." There was always an immense charm with this one. Martha had seen it from the start. "So no fencing."

"Once in a while. My flatmate's good with a foil."

"You're better with a saber."

"True. But he's not." Georg nodded toward the door. "So what's this all about?"

"A police matter."

"And?"

Ever the eager one. Hoffner had always thought it would send the boy into the Kripo, maybe a directorship. The imagination was obviously taking him elsewhere. "One of your executives put a bullet in his chest."

"Suicide?"

"So they tell me."

"It's a high-risk venture, Papi."

Hoffner was looking for another cigarette; his pockets were empty. "You're quite familiar with all this, then?" He found a box on the table and pulled one out: they were Luckys, not the easiest brand to find in Berlin. "Tell me, is anything in here not Americano?" He lit up and pocketed two more.

"It depends on the office."

"Grau?"

"The Herr Major? Strictly a Bergmann smoker. Maybe a few stubs from a Monopol MR in the ashtray, now and then."

"All this in two months? I'm impressed, Georgi."

The boy's face grew more serious. "Was it Thyssen?"

Hoffner was too good to give anything away. Even so, he knew the boy would be told soon enough. "Why do you ask?"

"A lot of late-night meetings. Unfamiliar faces."

Hoffner weighed his words carefully. "Faces you were meant to see?" Georg said nothing. "Not something you want to play at, Georgi. Leave it alone."

"I thought it was just a suicide?"

"Good. Then you can put your imagination to rest."

"It would make for a nice bit of script."

"I'll talk to Herr Ritter. See if he's interested." Hoffner nodded at the door. "I'll need forty minutes with that lot. Then I'll give you a ride back into town. Size up your flat."

Georg did his best to speak with authority. "I'm on until five-thirty."

"Not today you're not." Hoffner took a pull on the cigarette. "Herr Ritter and I are quite chummy. I'm sure they can do without you for one afternoon."

NO ONE HAD ANYTHING TO SAY. A trio of teary-eyed young secretaries and copyists spoke through handkerchiefs about the late, and quite marvelous, Herr Thyssen. More restrained, though no less captivated, were a messenger and a mailroom boy. Hoffner counted four crushes among them. "I've done a bit of mountain climbing myself," the fatter of the two boys volunteered. "Herr Thyssen was very accomplished, you know." At least now Hoffner had an explanation for the calloused fingertips. It was the only information worth jotting down.

Downstairs, Georg was waiting when he stepped from the elevator.

"You'll have someone keeping an eye out for you now," Hoffner said as he patted his pockets for a cigarette; the Luckys were long gone. "Good man, Ritter."

Georg showed only a moment's irritation as they moved down the hall. "I'll be fine on my own, Father."

It was the "Father" that gave it away. Georg rarely felt the need for it. Sascha, on the other hand, had taken it as his stock-in-trade. Funny how contempt could linger in the ears after eight years of silence.

"No reason not to have a few friends," said Hoffner.

Outside, the old Opel seemed somehow more lumbering squeezed in among the top-flight roadsters and saloons. Even they, however, looked almost brittle under the pale sun, as if the slightest touch might shatter their perfectly sculpted bodies. Hoffner brought his hand up to shade his eyes. "Quite a collection," he said. He pulled open the door.

Georg pointed to a red Brenabor sports coupe. "Jenny Jugo drives that one. She says she can get it up over a hundred on the circuit back to town."

"You've spoken with Jenny Jugo?"

"Sure."

Hoffner was beginning to see his son in an entirely new light.

"Lovely shoulders on that girl." Hoffner got in behind the wheel. "And lips."

"You should see her in the buff," said Georg as he pulled the passenger door shut.

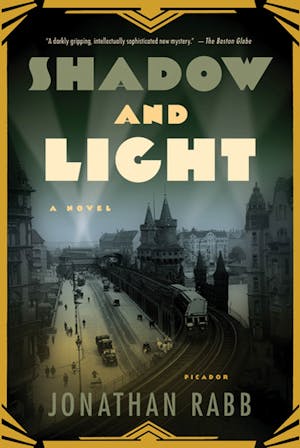

Excerpted from SHADOW AND LIGHT by JONATHAN RABB

Copyright © 2009 by Jonathan Rabb

Published in 2009 by Henry Holt and Company, LLC

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.