ONE

Mustard Seed Faith— With It You Can Move Mountains

Because you have so little faith, I tell you the truth, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, "Move from here to there," and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you. —Matthew 17:20

1969 Baltimore

At age nine I was a fourth- grader in a Catholic school, and the only whore I had ever heard of was the lady in the Bible. That was until one day when, dressed in my school uniform of blue pants, white shirt, and gray and blue striped tie, my mom picked me up and we set out on one of the defi ning adventures of my young life.

"Get in the car! We're going to that whore's house!"

It couldn't have been more than a ten- minute ride. My mother, who loves to talk, never said a word. We drove up on a busy street lined with row houses, each tipped with Baltimore's famed three- marble steps. I've never considered my mom an athlete, but that day she pushed at the driver's side door like a sprinter leaping off the starting block and quickly made her way to a house with a narrow door and a small diamond- shaped window. She rang the doorbell several times. A pretty woman with long curly brown hair fi nally answered the door. I was struck by how much she resembled my mother.

"Tell my husband to come out here," my mother yelled.

The woman answered, "I don't know what you're talking about" and slammed the door.

I could see the rage building in my mother's fi sts and across her face. She backed off the steps and screamed toward a window on the second fl oor,

"William Pitts! You son of a bitch! Bring your ass outside right now!"

There was dead silence. So she said it again. Louder. If no one inside that house could hear her, the neighbors did. People on the street stopped moving; others started coming out of their homes. My mom had an audience. I stood near the car, paralyzed by shame. Figuring it was her message and not her volume, my mother came up with a new line.

"William Pitts! You son of a bitch! You come outside right now or I will set your car on fi re!"

He apparently heard her that time. Much to my surprise, my father, dressed only in his pants and undershirt, dashed out of that house as my mother made her way to his car. She ordered me to move away from her car and get into my father's car. I did. My father was barefoot, and he slipped as he approached my mother. She picked up a brick and took dead aim at my father's head. She missed. He ran to the other side of his car. She retrieved the brick and tried again. She missed. He ran. My parents repeated their version of domestic dodge ball at least a half dozen times. It must have seemed like a game to the gallery of people who watched and laughed. I never said a word. In the front passenger seat of my father's car, I kept my eyes straight ahead. I didn't want to watch, though I couldn't help but hear. My parents were fi ghting again, and this time in public.

Eventually, my father saw an opening and jumped into the driver's seat of his car. Fumbling for his keys, he failed to close the door. My mother jumped on top of him. Cursing and scratching at his eyes and face, she seemed determined to kill him. I could see her fi ngers inside his mouth. Somehow my father's head ended up in my lap. The scratches on his face began to bleed onto my white shirt. For the fi rst time since my mother picked me up from school, I spoke. Terrifi ed, I actually screamed.

"Why! What did I do? Wha- wa- wa- wa- wut!"

I'm sure I had more to say, but I got stuck on the word what.Almost from the time I could speak, I stuttered. It seemed to get worse when I was frightened or ner vous. Sitting in my dad's car with my parents' weight and their problems pressed against me, I stuttered and cried. It seemed odd to me at that moment, but as quickly and violently as my parents began fi ghting, they stopped. I guess it was my mother who fi rst noticed the blood splattered across my face and soaked through my shirt. She thought I was bleeding. In that instant, the temperature cooled in the car. It had been so hot. My parents' body heat had caused the three of us to sweat. Fearing they had injured me, my parents tried to console me. But once they stopped fi ghting, I did what I always seemed to do. I put on my mask. I closed my mouth and pretended everything was all right.

I was used to this— there had been a lot of secrets in our house. My father had been hiding his infi delity. Both parents were putting a good face on marital strife for their family and friends. You see, almost from the time Clarice and William Pitts met, he was unfaithful. Women on our street, in church, those he'd meet driving a cab, and the woman who would eventually bear him a child out of wedlock. I have only known her as Miss Donna. Clarice may have despised the woman, but if ever her name came up in front of the children, she was Miss Donna. The car ride was a tortured awakening for me, but it was just the beginning. The picture our family showed the outside world was beginning to unravel, and when all our secrets began to spill into the open, on the street, in the classroom, and in our church, none of our lives would ever be the same.

My mother was accustomed to hard times. Clarice Pitts was a handsome woman, with thick strong hands, a square jaw, cold gray eyes, and a love for her children bordering on obsession. Her philosophy was always: "If you work hard and pray hard and treat people right, good things will happen." That was her philosophy. Unfortunately, that was not her life.

Clarice was the second of seven children born in a shotgun house in the segregated South of Apex, North Carolina, on January 1, 1934. By mistake, the doctor wrote Clarence Walden on her birth certifi cate, and until the age of twelve, when she went for her Social Security card, the world thought my mother was a man. Truth be told, for three- quarters of a century, she's been tougher than most men you'd meet. Her father, Luther Walden, was by all accounts a good provider and a bad drinker. He'd work the farm weekdays, work the bottle weekends. Her mother, Roberta Mae, was both sweet and strong. Friends nicknamed her Señorita because she was always the life of the party, even after back- breaking work. All the kids adored their mother and feared their father. On more than a few occasions, after he'd been drinking all day, her father would beat his wife and chase the children into the woods.

At sixteen, Clarice thought marriage would be better than living at home, where she was afraid to go to sleep at night when her father had been drinking. So she married a man nearly twice her age (he was twenty- nine), and they had one child, my sister, Saundra Jeannette Austin. People thought that since Clarice married a man so much older she would have a ton of babies. But she was never one to conform to others' expectations. She promised herself never to have more children than she could care for, or a husband that she couldn't tolerate. He never raised his hand to her. He did, however, have a habit of raising a liquor bottle to his mouth. She divorced him three years later, and by the mid- 1950s she and my sister had started a new life in Baltimore, Mary land, which held the promise of a better education and a better job than was available to her in the South.

She fi nally thought life had given her a break when she met William Archie Pitts. They met in night school. "He was a real fl irt, but smart," she said. In 1958 William A. Pitts could have been Nat King Cole's taller younger brother. He was jet black with broad shoulders; his uniform of choice a dark suit, dark tie, crisp white shirt, a white cotton pocket- square, and polished shoes. He dressed like a preacher, spoke like a hustler, and worked as a butcher. Clarice looked good on his arm and liked being there even more. He was ebony. She was ivory, or as Southerners said back then, she was "high yellow." My father had been married once before as well. His fi rst wife died in childbirth, and he was raising their son on his own.

After a whirlwind romance of steamed crabs on paper tablecloths and dances at the local Mason lodge, the two married. A short time later, I was born on October 21, 1960. There was no great family heritage or biblical attachment associated with my name. They chose my name out of a baby book. My mother simply liked the sound of it. One of the few indulgences of her life in the early 1960s was dressing her baby boy like John F. Kennedy Jr. She kept me in short pants as long as she could. She fi nally relented when I started high school. Just kidding. But to me it certainly felt as if she held on until the last possible moment.

Life held great promise for William and Clarice Pitts in the 1960s. The year after I was born, Clarice fi nished high school and later graduated college the year before my sister earned her fi rst of several degrees. She worked in a few different sewing factories in Baltimore. She took on side jobs making hats for women at church and around the city. Both of my parents believed God had given them a second chance. Almost instantly William and Clarice Pitts had a family: two boys and a daughter. My parents bought their fi rst and only home together at 2702 East Federal Street.

Outsiders knew my hometown as just Baltimore, but if you grew up there, there were actually two Baltimores; East Baltimore and West Baltimore. And the side of the city you lived on said as much about you as your last name or your parents' income. East Baltimore was predominantly blue collar, made up mostly of cement, ethnic neighborhoods, and tough- minded people. Most people I knew worked with their hands and worked hard for their money. You loved family, your faith, the Colts, and the Orioles. In 1969 my world centered on the 2700 block of East Federal Street. Ten blocks of red brick row houses, trimmed with aluminum siding. Decent people kept their furniture covered in plastic. Each house had a patch of grass out front. To call it a lawn would be too generous. The yards on East Federal were narrow and long, like the hood of the Buick Electric 225 my father drove. Those in the know called that model car a Deuce and a Quarter. Ours was a neighborhood on the shy side of working class. Like I said, my father was a meat cutter at the local meat plant. My mother was a seamstress at the London Fog coat factory. My sister was about to graduate from high school. Big hair. Bigger personality. I idolized her. My brother was sixteen. We had the typical big brother– little brother relationship: we hated each other. Born William MacLauren, we've always called him Mac as in MacLauren, but it could have stood for Mack truck. Not surprisingly, he grew up and became a truck driver. Even as a boy, he was built like a man, stronger than most, with a quiet demeanor that shouted "Fool with me at your own risk." He and Clarice Pitts were not blood relatives; however, they'd always shared a fi ghter's heart and a silent understanding that the world had somehow abandoned them. They would always have each other.

My nickname in the neighborhood was Pickle. I despised that name, but it seemed to fi t. You know the big kid in the neighborhood? That wasn't me. I was thin as a coatrack, my head shaped like a rump roast covered in freckles. We were a Pepsi family, but my glasses resembled Coke bottles. I was shy out of necessity. But what ever my life lacked in 1969, football fi lled the void. I loved Johnny Unitas, John Mackey, and the Baltimore Colts. I never actually went to a game. I guess we couldn't afford it. But no kid in the stands ever adored that team more than I did.

On Federal Street, the Pitts kids had a reputation: God- fearing, hard- working, and polite. Next to perhaps breathing, few things have meant more to my mother than good manners. She'd often remark, when I was very young, and with great conviction and innocence, "If you never learn to read and write, you will be polite and work hard." Most days, that was enough. Back in North Carolina, the only reading materials around my grandmother's home were the Bible and Ebony magazine. My parents did one better with the Bible, Ebony, and Jet. My father read the newspaper. My mother had her schoolbooks, but reading and plea sure rarely shared the same space in our house. Neither one of my parents ever read to me, as best I can recall. We had a roof over our heads, food on the table, and church every Sunday. When my mother compared our lives to her childhood— in which she and some of her siblings actually slept in the woods on more than a few nights, terrifi ed that their father would come home in a drunken rage and beat them— she felt that her children had it good.

Around the house, my mother was the enforcer, dishing out the discipline in our family. My father was the fun- loving life of the party and primary breadwinner. As long as I can remember, relatives from across the country (mostly the South) would call our home, seeking my mother's counsel. When there was trouble, people called Clarice. My dad loved cooking, telling stories, and occasionally, if encouraged, he would sing songs. The same relatives who often called my mom for advice would fl ock to our house annually to enjoy those times when my dad would cook their favorite foods, retell their favorite stories, and pour their favorite drinks. At some point in the eve ning, my mother would end up in my dad's lap, and neighbors could hear the laughter from our home pouring out onto the sidewalk. Those were the good days.

For better or worse, there was structure or, at the very least, a routine in the fi rst years of my life. My mother made my brother and me get haircuts every Saturday. We enjoyed one style: The number one. The skinny. And my mother's favorite, "Cut it close." Food was part of the ritual too. We'd have pot roast for Sunday dinner. Leftovers on Monday, fried chicken on Tuesday, pork chops Wednesday, liver on Thursday (I hated liver, so I got salisbury steak), fi sh sticks on Friday, and "Go for yourself" on Saturday. But mealtime was often the fl ashpoint for the anger and bitterness that began to consume my parents' marriage. Their fi ght scene on the street was a rarity, but Fight Night at the Dinner Table, as the kids called it, was a regular feature. Meals always started with a prayer,"Heavenly Father,thank you for the food we're about to receive . . . ," and often ended early.

The fi ght usually started with very little warning, either my mother's sudden silence or my father's sarcasm. One night we were having fried pork chops (so it had to have been a Wednesday). Pork chops were my favorite, with mashed potatoes and cabbage on the side, and blue Kool- Aid (that's grape to the uninitiated). The sounds of silverware against plates and light conversation fi lled the air. Then came the look. We all caught it at different times. My mother was staring a hole through my father's head. It sounded like she dropped her fork from the ceiling, but it actually fell no more than three inches from her hand to her plate. My dad gave his usual response soaked in innocence: "What?"

He didn't realize my mother had been listening on the phone in our kitchen when he had called Miss Donna from an upstairs phone to see how their son, Myron, was doing. Yes, I said their son. I think my mother was actually willing to forgive his child by another woman several years after my birth. But his name being so close to mine (Byron/Myron) was what seemed to break her heart and sometimes her spirit. At this point during dinner, however, she wasn't just broken— she was angry. First went her plate. Aimed at his head. And then her coffee cup. Then my plate. Followed rapid- fi re by Mac's and Saundra's dinner plates.

"Calm down, Momma!" Saundra, the ring announcer, screamed.

Mac, always the referee, stood up to make sure no one went for a knife or scissors. Me? I just sat there. You ever notice at a prizefi ght, the people with the best seats don't move a lot? They're spellbound by the action in the ring. That was me at the kitchen table: left side, center seat between my parents, my brother and sister on the other side. That night my mother was determined, if not accurate. Four feet away, four tries, but my mother never hit my father

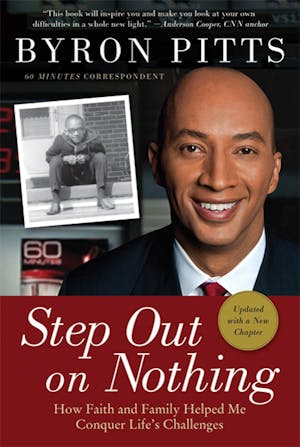

Excerpted from Step Out on Nothing by Byron Pitts.

Copyright © 2009 by Byron Pitts.

Published in October 2009 by St. Martin's Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproductionis strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.