1.

GIRL IN A LABYRINTH

AIDA AWOKE TO THE SMELL of homemade flour tortillas and the sound of her mother singing. Luz always sang the same song while she cooked—“Triste recuerdo” by Antonio Aguilar. Aida thought her mother sang beautifully. She poured out the long notes like honey from her brother’s ranch on the outskirts of Agua Prieta. Aida was eight, and her parents were the objects of her deep affection and contemplation.

Aida loved to sit on the couch watching her parents in the morning before school. Raúl and Luz made a funny, mismatched pair. He was in his early fifties, short, and taciturn. She, almost twenty years younger, was tall, loud, and güera. Aida didn’t understand her father’s meetings, or his books, but she knew that he’d once talked with the president of Mexico at a summit in Nogales. Now he worked at a Japanese factory assembling something, Aida didn’t know what. To eight-year-old Aida, her mother’s work was more exciting. Each morning, after Aida and her sisters left for school, Luz would open the small video and convenience store she ran out of the garage. When school was out, Aida would spend hours sitting beside her mother, surrounded by shelves of snacks and the clatter of dubbed action movies.

Those days had a regular, sunbaked rhythm in Aida’s mind. Agua Prieta was balanced on the northern rim of Mexico, tucked away from more important and populous parts of the country. In the 1990s, it had only just outgrown its cattle ranch roots. The city felt both small and large at the same time. Even on cold winter days, the sun was bright and Aida could play outside.

After school, Aida and her two sisters would come home and change out of their uniform skirts. They’d rush through homework under their mother’s watchful eye and shoot across the street to the playground. Aida was the middle sister, between Jennifer, age thirteen, and Cynthia, age six. The unexpected new babies, Jazmin and Emiliano, born a year apart, were still too small to count.

Nothing had come between the sisters yet. They ran and swooped and played with abandon. Dizzying themselves on the merry-go-round, their legs sweeping the sky, they squealed together in pure joy. They shot hoops with older boys and climbed anything that could be climbed. They knew every jagged metal splinter, every missing guardrail, and every trip hazard in the playground. They lived for the flawless moment suspended in the air after leaping into space.

The three sisters would only sit still after they had scaled to the top of the monkey bars. Taking in the whole playground, they would perch together at the apex, inventing futures for themselves, their six knees waving in the air.

“I’m going to live in los Unites and have a hot husband and daughter named Samantha,” Jennifer, the oldest, swore. The others agreed to follow her lead. To prepare for their future lives, Jennifer, Aida, and Cynthia practiced English. Usually this meant mimicking the sounds David Bowie made in Labyrinth, their all-time favorite movie. Sometimes they shouted the lyrics of “What’s Up?” by 4 Non Blondes, which mostly consisted of the word “Hey” repeated a million times.

“When I’m older,” Aida announced one day, “I’m going to live in a Big-Ass City. New York City.” With her baby lisp, it came out “Nuyorthittee.”

“Of course you are, little monkey,” Jennifer answered. “We know you will.”

* * *

SOME NIGHTS, Luz and Raúl attended a meeting of the Agua Prieta Search and Rescue Club. The girls would slip out to the playground after their parents left. While Luz and Raúl practiced searching for lost hikers with their club mates, Aida and her sisters danced under streetlights. Those forbidden nights on the playground all ended the same way: One of the other neighborhood kids would whistle a warning. Another would yell, “Hey, Hernandezes—your parents are coming!”

Aida and her sisters would rocket off the jungle gym in unison and hit the hard-packed dirt running. Aida knew the routine the way she knew the scars on her knees. She flew over the low fence and spun out of the park. She paused to help Cynthia cross the street, and then all three crashed through the metal gate of their house. Inside, skating across polished concrete, they landed on the couch—just as their parents’ car pulled up.

Raúl and Luz let themselves into their modest government housing unit and put down their things. Their daughters peeked up from the video they’d flipped on and were pretending to watch. Their parents wore matching tan Search and Rescue uniforms.

“Labyrinth again?” Luz asked.

Some nights Luz didn’t see through the act. On other nights she shouted until the house shook. “I thought I had girls. You don’t act like girls,” she’d yell on those nights. Girls don’t scrape knees or play outside after dark, she’d scold. Then they’d eat leftovers from the day’s big afternoon meal together, and Luz’s consternation would fade.

Days, weeks, and seasons passed in much the same way, there on the northern edge of Mexico. School, playground, tienda. Homework, playground, tienda. The sisters took care of their new siblings and watched videos. They managed not to break many bones. And they imagined that life would continue this way, like their one brakeless bicycle. And it did, until the night Raúl asked his question and the world fell out of balance.

* * *

THEY WERE EATING SUPPER. It began like any other bit of conversation.

“Luz, I have a question for you. I want you to be one hundred percent honest with me.” To Aida, it sounded ordinary, but Luz set her jaw into a ram.

“Girls, go to your rooms right now,” she said, not looking at her husband. It was the first of many bewildering commands Aida would obey that week. Huddled in her room with Jennifer and Cynthia, she didn’t get to hear the question or the answer. But she heard the recriminations and the screaming sobs that followed. The chairs clattering to the floor and ricocheting off the walls.

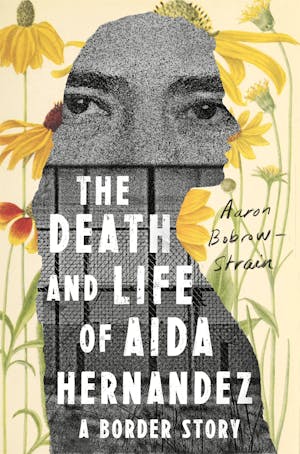

Copyright © 2019 by Aaron Bobrow-Strain