COMMUNION

We hold deep dark cups, dark like the cloth they bring out on Maundy Thursday to place over the cross and the tables at Hope Oak Church. I keep crying at the time of reflection, asking God for forgiveness (for kicking the neighbor’s dog, for shouting at the sky, for beating up that boy, and maybe even worse, for hurting Nicole). I can’t stop thinking about it—before I am told to eat the cracker and drink the two-inch cup of black-red wine.

Hold the cup tight enough and you can see your heart beating in the surface even when you doubt it’s there.

FIRST DAY BACK

People try not to look at us in the hallway. After we’d been suspended for two weeks, our classmates scatter like we might swallow them. Us, these angry brown boys ready to snap. What does it mean when we scare everyone—the good and the bad?

Maybe someday I will walk down the hall, and someone will see the human in me. It won’t be just Mom, God, and Max. Is Nicole in that group? I haven’t seen her since the woods, only DMing her my apologies. No response.

Max follows close behind, his coyote eyes averting, and I feel all my pull-ups bulk in my shoulders, my stomach, and in the veins that plump thick down my forearms. I keep my chin up. Keep my lips tight, and I am grateful that we are taller than most. This way, I can’t see their eyes, their fear of us. This way, I am not tempted to want more.

NICOLE

I go through the day without seeing her. Nicole and us, we are cousins, the complicated kind, but cousins nonetheless. She’s my father’s stepniece; her mother is his stepsister. Before Nicole’s parents divorced in fifth grade, she grew up just a few miles from us. She went to the same schools, and we were friend-cousins in class, inseparable, and family-cousins on holidays. She, her mom, her dad, her sister—Tia—were the only Native family we have on our dad’s side. She, her sister, and her mom enrolled at the Red Lake Nation. Dad’s side entwined by marriage.

Tia is a clothing and jewelry designer studying in New Mexico. She was the one to smooth-talk all the adults, the one with the coolest clothes, wearing designer brands she’d revamp from the steals she’d find at thrift stores or save up for at the mall. But Nicole has always been book brilliant. She’d be the first one to teach us something new. Psychology, herbology, ecology. The cousin who would take some distant relative’s baby in her arms and show us their reflexes. A finger for their hands to clasp, a graze to the cheek and they’d get all wide-eyed and hungry. I wonder if she somehow knows what everyone thinks. I know she now studies the mind, reactions, attachments, and misplacements. What did she learn about Max and me from that day in the woods? My stomach turns.

But she’s always had empathy—even for the bullies. Befriended most people at school. And I remember how Nicole cared for herself, too, making meals, doing her own laundry. Meanwhile, Max and I were just figuring out how often to shower.

Grandpa taught us to respect our relatives here and to know whose land we are on. The ever and always truth is that we, all of us, are on Anishinaabe land here in northeastern Minnesota. We are all on Nicole’s land.

COUNSELING

Max and I have our first meeting with the school counselor after our last classes. Ms. Hannan schedules us to meet with her together once a week after school, and closes her black calendar book. She wastes no time. She has us practice deep breathing, visualizing the ocean—a beach—what she calls our “safe place.” I smile and sense Max smirking through his breathing patterns. We know our people aren’t beach people no matter what our counselor might assume about Costa Rica. To us, the ocean is a fierce woman, and if we were there, traditionally, we’d have to pray to even get close. With Ms. Hannan, we try cognitive therapy, re-scaping our minds with warmer thoughts so we can prepare to talk to Luca for “reconciliation.” Our first session with Luca is tomorrow. After we do this, she asks us questions that start kind but build to:

Why didn’t you stop? Why did you kick him in the face? You broke his nose.

Which one of us broke his nose? Do we even remember?

His face is severely injured.

What can we say? We are sorry; we will never do it again?

We are angry, we finally say. This is true.

But we don’t know why. This is not true.

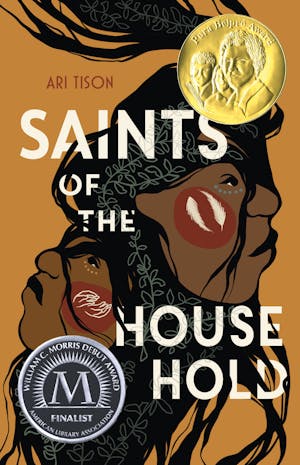

Copyright © 2023 by Ari Tison