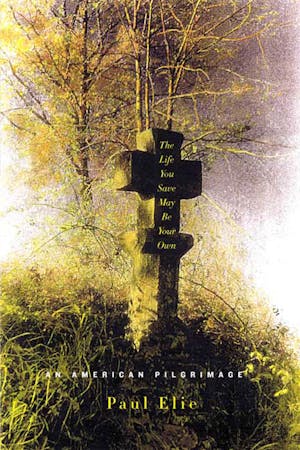

The Life You Save May Be Your Own

ONE

Experience

The night the earthquake struck San Francisco--April 18, 1906--Dorothy Day was there. Startled awake, she lay alone in bed in the dark in the still-strange house, trying to understand what was happening and what it meant, for she was confident that it had a meaning, a significance beyond itself.

Some years later she described that night in her autobiography. By then she was known as an organizer and agitator, a living saint, the prioress of the Bowery. But she saw herself as a journalist, first of all, and gave a journalist's eyewitness account of the event, which had brought on the most haunting of her early "remembrances of God."

"The earthquake started with a deep rumbling and the convulsions of the earth started afterward, so that the earth became a sea which rocked our house in a most tumultuous manner. There was a large windmill and water tank in back of the house and I can remember the splashing of the water from the tank on top of our roof."

She was eight years old, the third child of four. Her family had moved from New York to Oakland earlier in the year after her father, a journalist, found work with one of the local papers. Back in Brooklyn she had shared a bedroom with their Irish servant girl. Here she shared a room with her baby sister, who slept in her arms.

"My father took my brothers from their beds and rushed to the front door, where my mother stood with my sister, whom she had snatched from me. I was left in a big brass bed, which rolled back and forth on a polished floor."

Before getting into bed she had knelt at the bedside to say her prayers. Of all her family, she alone was religious: she prayed in school, sang hymns with neighbors, went to church by herself because the others would not go. She was "disgustingly, proudly pious."

In bed, however, she would have nightmares about God, "a great noise that became louder and louder, and approached nearer and nearer to me until I woke up sweating with fear and shrieking for my mother." And that night, alone in the dark on the big rolling bed, shaken by the earth, left behind by her mother and father, she felt God upon her once again, a figure stalking her in the dark.

Or was that night the first time? "Even as I write this I am wondering if I had these nightmares before the San Francisco earthquake or afterward. The very remembrance of the noise, which kept getting louder and louder, and the keen fear of death, makes me think now that it might have been due only to the earthquake ... . They were linked up with my idea of God as a tremendous Force, a frightening impersonal God, a Hand stretched out to seize me, His child, and not in love."

The earthquake went on two minutes and twenty seconds. Then it was over. The world returned to normal. She got out of bed and went down the stairs and out to the street and looked around.

She was startled all over again by what she saw: buildings wobbling on their foundations, smoke rising from small fires, parents calming strange children and passing jugs of water back and forth. People were helping one another.

For two days refugees from the city came to Oakland in boats across San Francisco Bay, making camp in a nearby park. The people of Oakland helped them--the men pitching tents and contriving lean-tos, the women cooking and lending their spare clothing. What did Dorothy Day do? She stood on the street, watching, and felt her fear and loneliness drawn out of her by what she saw.

"While the crisis lasted, people loved each other," she wrote in her autobiography. "It was as though they were united in Christian solidarity. It makes one think of how people could, if they would, care for each other in times of stress, unjudgingly in pity and love."

A whole life is prefigured in that episode. In a moment in history--front-page news--Dorothy Day felt the fear of God and witnessed elemental, biblicalcharity, the remedy for human loneliness. All her life she would try to recapture the sense of real and spontaneous community she felt then, and would strive to reform the world around her so as to make such community possible.

From the beginning, she had the gift of good timing, a knack for situating herself and her story in a larger story. Her first significant religious experience took place during the first great event of the American century, a cataclysm in the city named for St. Francis, the patron saint of "unjudging pity and love" for one's neighbor.

Moreover, it took place at a moment of great change (seismic change, one might say) in religion in America, and also in the interpretation of religion--changes to which she would spend the rest of her life responding.

There is little question that America at the turn of the century was a religious place. The question, then as now, was this: religious how?

At the time, the answer to the question was usually theological, grounded in stock ideas about Catholicism and Protestantism that had been developing since the sixteenth century. Catholics (it was thought) were traditional, communal, submissive to higher authority, taking faith at second hand from pope and clergy, whereas the Protestant was individualistic, improvisatory, devoted to progress, bent on having a direct experience of God, obedient to no authority save the Bible and the individual conscience.

From the time of Columbus, according to this scheme, which was accepted by Catholics and Protestants alike, the religious history of America was a running conflict between Catholic missionaries, who saw America as an annex of Catholic Europe, and Protestant pioneers, who saw it as a frontier to be settled according to the directives in the Bible.

In the nineteenth century Protestantism became dominant, and religion in America came to be characterized by the rivalry between different Protestant churches, whose circuit-riding evangelists would travel on horseback from one town to the next, each of them preaching a creed and a way of life that he claimed was more faithful to the Gospel than those his competitors were offering. Thus the country, discovered by Catholics, was settled by Protestants, whose work ethic became the basis of the national character.

Around 1900, however, the situation began to change. Because of immigration from Europe the Roman Catholic Church was suddenly the largest single church in America, with twelve million members. Taken all together, Protestants outnumbered Catholics seven to one, but when they thought of themselves separately, denominationally--as Baptists, Presbyterians, Unitarians,Methodists, and the like--they were outnumbered by Catholics, more of whom arrived each day.

As Catholics settled in New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, New Orleans, and other cities, the emphasis in American religion shifted from village and town to the metropolis. The spectacle of poor, dirty, ill-nourished people making camp on the outskirts of the city--such as the people Dorothy Day saw displaced by the San Francisco earthquake--became a familiar one, the subject of countless cautionary tales told among Protestants. And because so many of those people were Catholics, immigrant Catholics were the poor in the Protestant mind, and Protestant leaders, to care for them, devised the "social gospel," which sought to apply the New Testament to modern city life.

Competition between different Protestant churches, then, was overlaid by the competition between Protestants and Catholics, each group a majority that felt like a minority.

At the same time, conventional notions of Catholicism and Protestantism were being upended by the best and the brightest of the Protestant elite, in ways that challenged the standard account of American religious history and the usual understanding of religion generally.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) William James, who had had a religious experience all alone on a mountaintop after a long hike, defined religion as "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they consider the divine." For making the solitary individual the measure of religion, James is generally credited with shifting the study of religion in America away from institutions and toward experience. But his method of jumbling together believers of all sorts was just as important. He assembled his lectures from newspaper clippings about odd religious occurrences, and in his view the familiar distinctions between Protestants and Catholics, poets and saints, self-taught preachers and learned divines, were less telling than those between different religious temperaments: the "sick-souled" and the "healthy-minded," or the "once-born" and the "twice-born."

Meanwhile, James's Harvard colleague Henry Adams was being born again. In France in 1895 Adams, whose chronicle of the history of America ran to nine volumes, had undergone a religious conversion of sorts--not to God or Christ but to a mystical sense of history grounded in the Middle Ages and epitomized by the order and beauty and fixity, the sheer absoluteness, of the great French cathedrals. Declaring himself "head of the ConservativeChristian Anarchists, a party numbering one member," Adams wrote two books in which he sought to impress his vision of things upon the reader as boldly as possible. First came Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (1904), which is not so much a work of history as an imaginative pilgrimage, in which Adams slips into the skin of a French peasant who, in his view, saw and felt and understood life more directly than the stereotypical industrial-age American. Three years later came The Education of Henry Adams, Adams's third-person account of himself as a representative American man called Adams--whose problem, as he sees it, is that he is the descendant of pragmatic Enlightenment Protestants rather than of French Catholics, and so grew up with no knowledge of the religious energy that had inspired the cathedral builders of Europe--"the highest energy ever known to man."

Adams turned out to be a more representative man than he could have expected. Over the next twenty years, as The Education was read and embraced as a sacred text by the expatriate writers of the Lost Generation, France became, in American writing, a heaven, set in contrast to the hell of capitalist America, and the descent from the age of faith to an era of industry came to be seen as the fall from order to chaos, from civilization to barbarism, from community to an awful alienation.

Thomas Merton was ten years old when he first went back to France, the place of his birth and the setting of his father's paintings. Father and son set out by ship from New York, sailed to London and Calais, went by train to Paris and then to the south of France, the train racing through fields and towns--"over the brown Loire, by a long, long bridge at Orléans," Merton recalled in his autobiography, "and from then on I was home, although I had never seen it before, and shall never see it again."

He was a son of two artists. His parents--Owen Merton from New Zealand, Ruth Jenkins from New York--had met and been married in London, and Owen Merton, a landscape painter at a time when the French landscape was on the frontier of art, had gone to the Midi in search of an ideal place to paint. Thomas Merton was born there in 1915, and a brother, John Paul, in 1918. As America entered the world war they all went to New York to stay with Ruth Merton's family. Three years later she entered Bellevue Hospital, with stomach cancer, and she sent her elder son a note from her hospital bed to inform him matter-of-factly that she would never see him again.

Thomas Merton was six years old when his mother died. The next few years were hard ones. His father would go away to paint or to show his work, leaving him and his brother on Long Island with their grandparents. He went to school on and off. He read the Tom Swift books at his grandfather's office in a New York publishing house. He watched W. C. Fields make a movie in a vacant lot. And he prayed, following his father's instructions, asking God "to help him paint, to help him have a successful exhibition, and to find us a place to live."

Then, in the summer of 1925, Owen and Thomas Merton went to France. As they settled one night in a small hotel in an ancient village, "I felt at home. Father threw open the shutters of the room, and looked out on the quiet night, without stars, and said: 'Do you smell the woodsmoke in the air? That is the smell of the Midi.'"

They traveled for several weeks. In The Seven Storey Mountain Merton recalls the places they passed through--a bend at the base of a cliff with a castle on top; hayfields running down to the river, crossed by cattle tracks or dirt roads; a gorge with cliffs rising away on both sides, dotted with caves to explore--and describes them with painterly precision, until the point in the story when they reach their destination, the village of St. Antonin, whereupon he reverts to his own language, that of religious experience.

St. Antonin was an ordinary village, encircled by a road where the ancient ramparts had been. The ruined buildings were recognizably medieval, except for the church in the center, which was modern. But it was the plan of the town, not its beauty or its history, that struck Merton most powerfully. He explained, "The church had been fitted into the landscape in such a way as to become the keystone of its intelligibility ... . The whole landscape, unified by the church and its heavenward spire, seemed to say: this is the meaning of all created things: we have been made for no other purpose than that men may use us in raising themselves to God, in proclaiming the glory of God."

As he writes, twenty years have passed and he is cloistered in the Abbey of Gethsemani, the closest thing to a medieval French village to be found in America. The order and unity of the French village, he believes, are the attributes of the Catholic faith, and their fulfillment is the monastery; the longing he first felt as a boy in France he has satisfied as a Trappist.

There is more to it than that, however. The son of a painter, he describes the village so as to give it the wholeness and harmony and radiance of a landscape painting. He, too, will wind up a painter of landscapes in his way,for in entering a monastery he has sought not just to return to France or the Middle Ages but to enter into the vision he had seen over his father's shoulder in St. Antonin that summer, in which the imperfect world was made perfect in the mind's eye.

The Catholic immigrants who came to America came for good: most of them never returned to the old country. Yet in America, as in Europe, they still clustered by nationality: Irish, German, Italian, Polish, Mexican, canadien français. They had their own folkways and old-style devotions, a certain way of kneeling or clasping the hands. Their parish churches went up brick by brick in their neighborhoods: St. Stanislaus for the Poles, St. Philip Neri for the Italians, Our Lady Star of the Sea for the Irish longshoremen. Their processions filled the narrow streets where they were tenemented, the plaster Virgin or patron saint bobbing above a great wave of them during the feast-day parade.

Today those immigrant neighborhoods are romanticized as outposts of the Old World, where community was palpable and the Church was at the center of people's lives. But to the Catholic immigrants--peasants, most of them--those neighborhoods, all gridlike streets and upright tenements, clamorous subways and motorcars, were nothing like the villages where they had once lived, and life in America, for all its promise, was shot through with the sense of what they had left behind. The regional touches in the neighborhoods were secondhand, imitative, brought fully to life only by the memories the immigrants carried around in their heads; and American Catholicism, likewise, was a reconstruction effort, in which religious faith involved remaining faithful to the old country and the old ways, lest they be lost forever.

Thus the Northern cities rose on a bedrock sense of loss, which was covered over with expectation. In the South, meanwhile, the sense of loss was out in the open. The region had been settled--founded--on an ideal of decline and fall, and the Civil War gave this ideal a powerful, biblical warrant. With defeat (the white planters concluded) all was lost: the lives of the young men who had died in the fighting, the free labor of the slaves, the civilization their big houses embodied, their sense of dominion over the territory. Whereas the Northern immigrants recalled a distant homeland, the Southern gentry looked back to a supposedly nobler age.

So it was that even before his father killed himself and his motherdrowned, Walker Percy was haunted by loss, beset by the sense that a better time had preceded his, that he was living in the aftermath of his people's story.

The Percys were a self-fashioned great family of the South, and their lineage has fascinated Walker Percy's biographers. They claimed descent from an old Scottish clan. Henry Percy was Shakespeare's model for Harry Hotspur in Henry IV, Part I. At the turn of the century LeRoy Percy was elected a U.S. senator from Mississippi.

Percys were melancholy people, and their prominence seems to have compounded their sadness. There was a suicide in nearly every generation. One Percy man dosed himself with laudanum; another leaped into a creek with a sugar kettle tied around his neck. John Walker Percy--Walker Percy's grandfather--went up to the attic in 1917 and shot himself in the head. LeRoy Pratt Percy--Walker Percy's father--committed suicide in 1929 in precisely the same manner.

That branch of the family lived in Birmingham, Alabama, where Walker Percy was born in 1916, the eldest of three boys; but after the suicide Mrs. Percy took her sons to Georgia, where her own family lived. Shortly afterward William Alexander Percy paid them a visit there. His legend preceded him: veteran of the foxholes in the Great War; Harvard-trained lawyer; plantation overseer; poet whose books were published by Alfred A. Knopf in New York; foreign traveler, who was just back from an excursion to the South Seas. "He was the fabled relative, the one you liked to speculate about," Walker Percy recalled. "The fact that he was also a lawyer and a planter didn't cut much ice--after all, the South was full of lawyer-planters. But how many people did you know who were war heroes and wrote books of poetry?"

Will Percy was forty-five years old. His parents, with whom he had lived for some years (he was a confirmed bachelor), had died the previous year, and their big house in Greenville, Mississippi, was empty. He invited Mrs. Percy and her sons to live with him there, and they accepted the invitation.

Three years later Mrs. Percy died in a car accident, driving off the road and into a creek, where she drowned. Walker Percy, now nearly sixteen, was riding in a car not far behind; he leaped out, but bystanders kept him from seeing the accident site firsthand. He and his brothers were now orphans--their mother's accident was a suicide, some said--and William Alexander Percy adopted them.

"Uncle Will" Percy lived up to his legend. He was a tireless pedagogue,expatiating on the novels of Walter Scott and the symphonies of Beethoven. He stood up for "his" Negroes in town in the paternalistic way of the time. In life and poetry alike he was a moralist and self-styled exemplary man, asking those around him, "What do you love? What do you live by?"

He exhorted his adoptive sons to model their conduct on his, and they did so, the eldest son in particular. When he arrived in Greenville (he later claimed) Walker Percy was "a youth whose only talent was a knack for looking and listening, for tuning in and soaking up"; Uncle Will, he said, gave him "a vocation and in a real sense a second self," inspiring him to become a writer.

But Will Percy was not an exemplar for Walker Percy simply because he was a writer. He was also an exemplar of the Percy melancholia. No less than Percy's natural father, he was wracked with a sense of loss; for all his learning, his wide experience of the world, his love of art, his principles and philosophy, the man who paced the parlor of the house in Greenville and recited poetry while a symphony played on the phonograph was no happier than the man who had gone up to the attic in Birmingham one Tuesday afternoon and put a gun to his head.

In the family plot in the cemetery in the center of Greenville there stood a life-size statue of a square-jawed man clad as a medieval knight, in cape and chain mail, hands crossed over a sword. It was a likeness of William Alexander Percy's father, which Will Percy had commissioned as a burial monument, a monument to his ideals and the loss of them.

Some years later, the nature of Will's ideals--and of the loss of them--became clear to the Percy boys, Walker especially. As a boy, it turned out, Will had had a religious conversion. Although he was raised an Episcopalian, his mother had been a Catholic, and she saw to it that he was tutored by nuns and a priest. When he was ten years old, the Catholic faith overwhelmed him in a violent attack like the ones described in the lives of the saints. All of a sudden he was praying mightily, fasting "on the sly," confessing the slightest of sins, and imagining that he was a monk in a cave in a desert. "I wanted so intensely to believe, to believe in God and miracles and the sacraments and the Church and everything. Also, I wanted to be completely and utterly a saint; heaven and hell didn't matter, but perfection did."

Five years later he still wanted to be a priest, but he was sent away to college at the University of the South, as Percy tradition dictated. The school, set atop a mountain in Tennessee, had an Episcopal chapel on the grounds, but one Sunday morning a month Will would mount a horse and ride theten miles down the mountain to go to Mass at a Catholic church in the valley.

During his sophomore year the news came that his youngest brother had been shot. It was an accident: hunting with a friend, the boy was wounded in the stomach; he died a week later.

One Sunday--before or after, he did not say--Will rode down the mountain to Mass as usual, but when he reached the church he found that his faith was gone. As he rose to go to confession, he recalled, "I knew there was no use going, no priest could absolve me, no church could direct my life or my judgment ... . It was over, and forever."

Truly, his life was just beginning, but in him the family legacy of nobility and loss had already catalyzed into a tragic worldview. As time went on, he lived a distinctive life--as a bachelor who was also a father, a pillar of the community who was also an artist, an exemplary man who was also (Walker Percy said) "unique" and "one of a kind."

In William Alexander Percy the double aspect of the family legacy was apparent in all its complexity. Looking and listening, aspiring and imitating. Walker Percy evidently glimpsed early on what his own calling would be, although half his life would pass before he fully grasped it and put it into words. He was called at once to uphold the family history and to defy it, at once to emulate it and to diagnose it--to find the way of being a Percy that was distinctly his, so as to break the pattern of melancholy, loss, and violence against the self that ran down the generations.

"When I was five," Flannery O'Connor recalled, "I had an experience that marked me for life. The Pathé News sent a photographer from New York to Savannah to take a picture of a chicken of mine.

"This chicken, a buff Cochin Bantam, had the distinction of being able to walk either forward or backward. Her fame had spread through the press, and by the time she reached the attention of Pathé News, I suppose there was nowhere left for her to go--forward or backward. Shortly after that she died, as now seems fitting."

Compared to an earthquake or a parent's suicide, a chicken's fleeting fame seems hardly revelatory. But this story is the most personal story O'Connor ever told, and, along with the Pathé short, it is the most vivid picture there is of her earliest years.

She was born in 1925 and grew up an only child, adored and precocious,called Mary Flannery. As Catholics, her family were exceptional in Georgia, where Catholics made up only a fraction of the population. As prosperous people, they were exceptional among the Catholics. A relative in Savannah owned the townhouse they lived in there, catty-corner from the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, and had staked her father in the real-estate business. Her mother's family, the Clines, lived in a grand house in Milledgeville, a morning's drive north, and Mary Flannery went to visit them in the summers, playing between the tall whitewashed columns on the porch steps. Her uncle Bernard had a medical practice in Atlanta but spent weekends in Milledgeville, at a dairy farm on the edge of town.

As Southerners, moreover, they were exceptional in the eyes of people from the North, such as the Pathé cameraman from New York. Mary Flannery O'Connor hadn't asked him to come, but he came into their yard and stuck his camera into her life and gave her the idea that she was up to something out of the ordinary.

The newsreel short was shown in movie houses not long afterward. It opens with the title UNIQUE CHICKEN GOES IN REVERSE. A girl in a black coat and skullcap--a city girl--comes along cradling a chicken in her hands. She sets it down and watches it with eyes full of concentration as it begins to walk, forward and then back. "Odd fowl goes backward to go forward so she can look back to see where she went," says the caption. Then the camera withdraws and the film is suddenly reversed, so the geese and cows walk backward, too.

The episode lasts less than a minute. Yet Mary Flannery O'Connor had been changed by it. She perceived that she had an unusual gift, even if it was just a gift for getting a certain kind of chicken to walk a certain way; and she saw that her challenge in life would be to make the nature of her gift clear to people who wouldn't understand it otherwise.

She began to collect chickens, to give them striking names, to dress them in little outfits she sewed for them. "What had been only a mild interest became a passion, a quest. I favored those with one green eye and one orange one or with overlong necks and crooked combs but nothing in that line turned up. I pondered over the picture in Robert Ripley's book, Believe It or Not, of a rooster that had survived thirty days without his head."

She was drawn to what she would call "mystery and the unexpected." It was a mystery why the chicken could walk either forward or backward, not just forward as it was expected to do. The chicken was a freak, a grotesque, and when a cameraman came all the way from New York to Savannah tophotograph her just because she had trained it, she was suddenly a kind of freak, too.

When she told the story in an essay thirty years later, she had devoted her life to the aesthetic contemplation of the grotesque.

The grotesque character or freak plays various roles in her work, serving a broad range of dramatic purposes. The freak is an image of human nature deformed by sin, as is the Misfit in "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," or an instance of human nature transformed by God's grace, as Hazel Motes is at the end of Wise Blood. The freak is a figure for modern man, like the psychologist Rayber in The Violent Bear It Away, reduced by the scientific worldview to an aggregate of tendencies and statistics; or a character deliberately distorted by the author, like the tattooed O. E. Parker in "Parker's Back," so as to startle the unwitting reader to attention.

Finally, the freak stands in for the author. She explained, "It is the way of drama that with one stroke the writer has both to mirror and to judge. When such a writer has a freak for his hero, he is not simply showing us what we are, but what we have been and could become. His prophet-freak is an image of himself."

Solitary, strange, physically weakened, often misunderstood, and yet sustained by a belief, so strong as to be religious, that she was exceptionally gifted, Flannery O'Connor was so unique as to seem to others a kind of freak; and her girlhood encounter with the Pathé cameraman from New York was her conversion to the grotesque and the freakish, the moment in which she came to firsthand experience of the phenomenon she would write about.

From San Francisco the Days moved to Chicago, settling on the South Side and then on Webster Avenue, near Lincoln Park. Dorothy Day did well in high school and won a scholarship to the state university in Urbana, a hundred miles downstate. She had a severe beauty: a jutting chin and cheekbones, big deep-socketed eyes. She had gone ahead and gotten baptized in the Episcopal church in the neighborhood. After school, as she pushed her new baby brother in a carriage toward the park and Lake Michigan, she would hum psalms she'd heard in church to express the joy in life she felt.

Yet she was restless, hungry for the direct experience of life, in, say, a great event like the Russian Revolution, which she had written a term paper about. "Maybe if I stayed away from books more this restlessness would pass," she told a friend. "I am reading Dostoevski and last night I stayed uplate and this morning I had to get up early and I feel that my soul is like lead."

Her father, apparently threatened by her independence, forbade the Day children to leave the house alone. So Dorothy would sit in the room called the library and read, day and night: Dostoevsky, Jack London, Frank Norris, Upton Sinclair, the "revolutionist" Peter Kropotkin, The Imitation of Christ.

Sinclair's The Jungle was set in the slums of Chicago's West Side, and the setting struck her powerfully. Now when she went out to push her brother in his carriage she walked west, right into the world of the novel. She was startled to find that life itself was just as Sinclair had described it. Passing taverns, she imagined scenes from the book taking place inside, and she felt joined to the people whose fictional counterparts she had read about.

"Though my only experience of the destitute was in books," she recalled in her autobiography, "the very fact that The Jungle was about Chicago where I lived, whose streets I walked, made me feel that from then on my life was to be linked to theirs, their interests were to be mine: I had received a call, a vocation, a direction in my life."

In September 1914 she left Chicago for college. In Urbana, she made friends with a professor who was a Methodist and passed time with his family, talking about faith. She joined the Socialist Party, but found the meetings boring. She fasted for three days, eating nothing but peanuts, in order to write a personal essay about the experience of hunger.

She was homesick. Alone, missing the baby brother she had helped to raise, she read her way out of her loneliness. "I read everything of Dostoevski," she recalled, "as well as the stories of Gorki and Tolstoi." Fiction became a home away from home, vivid and full of companionship. It comforted her better than religion could, for even as novels gave solace they cried out against injustice.

In 1914 Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were the great novelists of the age just past. Tolstoy had died only in 1910, and in his later years he had become a figure of legend: a man who had renounced novels to write religious parables, who had left his large family and vast estate to wander the country like the archetypal Russian in The Way of a Pilgrim--a man "alien to all," Gorky recalled, "a solitary traveler through all the deserts of thought, in search of an all-embracing truth which he has not yet found." Tolstoy called himself a Christian anarchist, but his pacifist, celibate, literal acting out of the Gospel led people to mock him as a "Tolstoyan," and his late works were read not as art but as imaginative statements of the ideals he was striving toward.

Dostoevsky had the opposite reputation. Though he had died in 1881, ageneration passed before his books were translated into English. He was thought to have been like one of his hapless characters, a drunkard, gambler, debtor, epileptic, fanatic, ex-convict, and all-around unfortunate man. The events of his life were like real-life parables--the lifting of his death sentence while he stood before a firing squad, his conversion to Christianity in a prison in Siberia--and the religious torments he wrote about had the electric charge of the real thing, of experience that had been thrust upon him against his wishes.

Together Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were the two halves of the Slavic soul: the debased man whose suffering united him to all humanity and made him holy, the highborn man who sought out suffering as a means of enlightenment. Each had struggled with God and put the story into his books, urging his readers to carry on the struggle in their own lives.

Day read them and accepted their challenge. Yet the religious ardor of Russian fiction could not be reconciled with the docile Christianity of Urbana, Illinois, a place as yet untouched by modernism or the Great War. "Both Dostoevski and Tolstoi made me cling to a faith in God, and yet I could not endure feeling an alien in it. I felt that my faith had nothing in common with that of the Christians around me ... and the ugliness of life in a world which professed itself to be Christian appalled me."

She was eighteen years old. Like a Dostoevsky character, she cursed God, and decided that religion was a crutch for the weak, an opiate of the people.

Her family had left Chicago to return to New York, and she quit school and followed them. New York, full of immigrants, was also the American city where socialism was thriving. There, she would live the life the great Russian novelists had written about.

The next years might have come straight out of The Possessed, Dostoevsky's novel about the "cells" of radicals in czarist Russia.

"During that time I felt the spell of the long loneliness descend upon me," Day later wrote. Mornings she would set out on the streets of lower Manhattan, looking for a job with one of the socialist papers. There were no jobs to be found. "In all that great city of seven millions, I found no friends; I had no work; I was separated from my fellows. Silence in the midst of city noises oppressed me. My own silence, the feeling that I had no one to talk to overwhelmed me so that my very throat was constricted; my heart was heavy with unuttered thoughts; I wanted to weep my loneliness away."

In time she got a job with The Call and started to write. As she walked the streets, notebook in hand, amid the smells of dirty laundry and rotten food and garbage--"the smell of the grave," she called it--she realized that she didn't want to report on poverty: she wanted to live it firsthand, as the poor did.

She was still reading the Russian novelists, and was "moved to the depths of my being," especially by Dostoevsky. "I read all of Dostoevsky's novels and it was, as Berdyaev says, a profound spiritual experience," she recalled. "The scene in Crime and Punishment where the young prostitute reads from the New Testament to Raskolnikov, sensing sin more profound than her own, which weighed upon him; that story 'The Honest Thief'; those passages in The Brothers Karamazov; Mitya's conversion in jail, the very legend of the Grand Inquisitor, all this helped to lead me on."

She studied the anarchism of Emma Goldman. She interviewed Leon Trotsky. She went to Webster Hall for the Anarchists Ball and to Madison Square Garden to celebrate the 1917 revolt in Russia, and was caught up in the "mystic gripping melody of struggle, a cry for world peace and human brotherhood" in the midst of senseless world war.

But her comrades said she would never be a good Communist, because she was too religious--a character out of Dostoevsky, a woman haunted by God.

She had gotten a job with The Masses, a stylish socialist magazine, but it was shut down by the government. At loose ends, she went to Washington to take part in a rally for women's suffrage. With several dozen others, she was arrested and sentenced to thirty days on a disorderly conduct charge. She was startled by what she saw. The women were kept fifteen to a cell; they rioted, and were locked up in pairs. They went on a hunger strike: twice a day for six days toast and milk were brought, and they refused to eat. They yearned to be let go. There was nothing to do, nothing to read or write with. On the floor, hungry and exhausted, Day and her cellmate passed the time by discussing Joseph Conrad's novels.

"It was one thing to be writing about these things," she recalled, "to have the theoretical knowledge of sweatshops and injustice and hunger, but it was quite another to experience it in one's own flesh."

Now she knew suffering firsthand, as the poor did, and what was more, she knew what it was to feel, as they did, that it was her own fault, a consequence of her own rebellious nature. "I was a petty creature," she told herself, "filled with self-deception, self-importance, unreal, false, and so, rightly scorned and punished."

Brought low, she asked for a Bible, the way Dostoevsky, seventy years earlier,in a prison in Siberia, had asked a guard for a Bible, which he read over and over again until he was a believer.

Three days later a Bible was given to her. She read and read. The ancient words spoke to her, a voice from her childhood, familiar and comforting. "Turn again our captivity, O Lord, as a stream in the south. They that sow in tears shall reap in joy": as she pondered that biblical verse she applied it to the suffragists' plight, and decided that "if we had faith in what we were doing, making our protest against brutality and injustice, then we were indeed casting our seeds, and there was promise of the harvest to come."

She was freed after two weeks. She had been changed--radically changed. Dostoevsky's novels had so taken root in her that she had begun to follow their pattern, to conform her life to the lives he described. But she was not a character out of Dostoevsky, a prisoner of her nature. By nature she was a Tolstoyan, ardent for suffering, free to choose it, and the desolation of jail was an experience that she, inspired by fiction, had actively sought.

Shortly before the Percy brothers moved to Greenville Uncle Will had taken another boy aside at a local country club and asked him to make friends with "some kinsmen of mine."

Shelby Foote was an only child, and his father had died of septicemia (a bacterial infection) a few years earlier. He was thirteen years old, a few months younger than Walker Percy. The house where he lived with his mother and an aunt was not far from Will Percy's house, and during the next few years he all but lived with the Percys, joining the odd family as a kind of fourth brother. He became closer to Walker Percy than Percy's blood brothers were: a best friend, a boon companion, a scold, a rival. And he introduced Percy to modern literature, beginning a conversation about books that would last the rest of their lives.

Percy was already being raised on books by his Uncle Will. He wrote poems "in the manner of" Poe and Blake for his classes, articles for the Greenville High School paper, and the paper's gossip column as well. One piece was about "Africa--Land of Race Problems," another about a soup kitchen in the black section of Greenville, where he found "an ill-sorted array of our darker citizens in a straggling sort of line receiving food." But in those years Foote, more than Percy, was the aspiring writer; and whereas Percy (like his Uncle Will) read the classics, Foote favored modern literature.

In their senior year of high school Percy read The Brothers Karamazov.Perhaps Foote recommended it; perhaps he came to it on his own. In any case, he read the novel straight through over three or four days on the big porch of the house in Greenville, hardly putting it aside to live his own life. His father had killed himself, and here was a book about four brothers who wanted to kill their father; his mother had died in a car crash, and here was a book about the question of whether there can be a God in a world in which innocent people suffer.

A few years later Foote gave his own copy of The Brothers Karamazov to Percy at Christmastime, putting an inscription on the flyleaf. The inscribed book suggests the role literature would play in their friendship. For the next fifty years they would have what Percy called "long Dostoevskian conversations" about writing and writers, especially Dostoevsky. Foote would read The Brothers Karamazov six times more, exclaiming over it each time; Percy would think of it as the book that had opened the most possibilities for him, for it showed how a novelist could write in response to ideas, combining literature and philosophy.

The book, and the conversations it inspired, also suggested Percy's developing conviction about reading and writing. For him literature would not be a private affair, but the stuff of influence and exchange and dialogue, which the books themselves called forth. The literary life would consist of friendship, and of spirited disagreements over books and their implications.

A photograph taken of the two friends in Greenville suggests the bond that formed between them. Percy is draped over a garden chair--gangly, his hair slicked back, wearing a V-neck sweater and a sports jacket and saddle shoes and dandyish striped socks. Foote, darkly handsome, is next to him, stretched out on a chaise longue. Percy's younger brother Phinizy is to their left, with them and yet, it seems, outside their conversation.

All the while, Percy's biographers report, he was growing expert in science, chemistry in particular. As college approached he had to decide which field to study in greater depth. After reading The Brothers Karamazov, he recalled, he was drawn to literature, "but I abandoned it then for science (like Ivan in the book)." A trip to the World's Fair in Chicago--which, Percy later recalled, put forward a "technological vision" of "future happiness"--seemed to confirm his choice. For the next twenty years, like Ivan Karamazov, Percy would see science and art as in opposition in his own life, presenting competing notions of truth and of the meaning of life. At the time, he explained later on, science seemed to have the better answers: clear, logical, verifiable, true at all times and places. But it may be that hechose science, and eventually medicine, for a deeply personal reason as well. There were no scientists or doctors in the Percy lineage. His Uncle Will was a writer. So was his best friend. The two of them were tireless pedagogues, and they doubtless offered as much advice and counsel as Percy could bear. In abandoning literature for science, perhaps he sought to escape their influence--to find a way of life in which, like Ivan Karamazov, he could draw conclusions in light of his own experience, not somebody else's.

Owen Merton, settling in St. Antonin, decided to build a house there; and just as the layout of the village, with its suggestion of a prior order and splendor, had come to define the place, and the Catholic world, in Thomas Merton's mind's eye, so the house came to characterize his life with his father.

Owen bought some land at the foot of a hill called Calvaire, or Calvary. At the top there was an old stone chapel, and the path up was marked with the Stations of the Cross.

Diviners tested for springs on the property. Workmen dug a well. Meanwhile father and son visited the neighboring villages, looking at churches and abbeys as models for their own design. At night, in their rented rooms, Merton would turn the pages of a picture book about France and gaze at the photographs of old churches in it: St. Denis, Chartres, the abbey at Cluny, a Carthusian hermitage clinging to a hillside.

His father sketched a simple dwelling, light, low, square, stone, and surrounded by a garden. "It would have one big room," Merton recalled, "which would be a studio and dining room and living room, and upstairs there would be a couple of bedrooms. That was all."

One day they went to a wedding in the village, followed by a feast in an old barn. At dusk some townsmen led them out behind the barn. There in a pasture was another abandoned chapel. Its stone walls glowed in the waning light. They stood admiring it. "I wonder what it had been: a shrine, a hermitage perhaps? But now, in any case, it was in ruins. And it had a beautiful thirteenth- or fourteenth-century window, empty of course of its glass."

Owen Merton decided to buy the chapel then and there and have it transported to his own land. Out of its ruins they would build their house. Its stones would surround them. Its Gothic arch would loom overhead. Through its window father and son would look out.

In St. Antonin, Merton tasted the direct experience of life. There, he was the hero of the adventure story that was his boyhood. The past was his playground. Life with Father was life itself. And as the house went up, he was avisitor no longer, but a villager like everyone else, a French boy who had found where he belonged. "Sometimes I think I don't know anything except the years 1926-27-28 in France," he wrote in his journal some years later, "as if they were my whole life, as if Father had made that whole world and given it to me instead of America, shared it with me."

St. Antonin, in Merton's writing, is a kind of paradise, and he will spend his adult life trying to recapture the directness and immediacy of experience he had known there. No matter how strenuous his self-denial, his imitation of Christ and the saints, he will never want to be anybody but Thomas Merton, French-born son of a landscape painter. For him the vital religious questions will always be variants of the question: Who am I, and who am I meant to be? In this sense he is a representative, even a typical, modern person, whose strong sense of self is constantly met by the sense that the self and its preoccupations are unworthy or illusory. His answers will always involve a pledge to devote himself to an ideal way of life, and this way of life will be bound up with an ideal setting: a space, a place, a destination, a habitation. If only he can find the place where he is meant to be, he will tell himself, he will become the person he is called to be--will fulfill his God-given nature.

He will be a mystic of places and spaces. Churches and chapels and monasteries and hermitages will be expressions of his ever-changing religious ideals. In the spirit of a long mystical tradition, he will make them symbols of what mystics call "the interior life." He will write about the soul as a work of sacred architecture, elaborately figured and consecrated; he will write about the religious life as a work in progress, like a cathedral that stands unfinished for a hundred years. Out of poems and essays and autobiography he will make a religious compound, to which readers can come as if on a pilgrimage, a new place made of remnants of the Catholic past.

The house in St. Antonin was left unfinished. Father and son left for London to attend a show of Owen Merton's landscapes, and never returned. It was a loss Merton felt the rest of his life. "It is sad, too, that we never lived in the house that Father built," he wrote in his autobiography, the book in which he began to complete the structure he and his father had designed. "But never mind! The grace of those days has not been altogether lost, not by any means."

The United States, by then, was in some ways as Catholic as France. In the decades after 1900 the American Catholic population had grown to twenty million, almost a fifth of the U.S. population.

Writers looking for the American past now looked to the Catholic past. D. H. Lawrence interpreted the work of Hawthorne, Melville, and the like as a "complex escape" from the Old World, a search for "something grimmer" than the "new liberty" of enlightened Europe. William Carlos Williams, in In the American Grain, related the legend of Père Sebastian Rasles, a French Jesuit missionary whose death, in Williams's telling, spelled the death of the Catholic claim on America--and the death of American Protestantism as well, for without an established church to oppose, Puritanism had grown fatally narrow and self-righteous.

Meanwhile, with American Catholics ever more numerous and more various, the leaders of the church in the United States sought, through various stratagems, to unify them.

The Baltimore Catechism--its very name fragrant with Americanness--instilled the habit of imitation. "Q. Why did God make you? A. God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world and to be happy with Him forever in the next"--the catechism's question-and-answer presentation of the tenets of the faith oriented Catholic education, and Catholic life generally, around the ritual echo of authority, the adoption of someone else's questions and answers as one's own.

The parochial school system applied the pattern of imitation on a vast scale. By schooling them together, the system gave Catholic children of many nations a common store of knowledge, as well as a common language, English. And by keeping them separate from Protestants the schools made separateness a source of unity and pride, instilling in young Catholics the belief that their way of life was separate from, and superior to, the Protestant one.

The system became so pervasive that it is taken for granted. But its stress on separateness actually was a departure from the usual theological notions of Catholicism and Protestantism. In Europe, where the Catholic Church was present as early as the fourth century, the impulse to separate oneself, to stand apart, was associated with Protestants, and since the time of the Reformation the Catholic Church had seen separatism as the egregious sin of Protestantism, condemning the Protestant churches as wayward children who had spitefully broken off relations.

Now, in North America, it was the Catholics who stood apart. Even as they made their way in society, as shopkeepers and laborers, police officers and politicians, they were taught to cherish separateness as a virtue, the worldly expression of the virtue of purity sought in convents and monasteries.

Separate in their minds and hearts if not in actual worldly fact, Catholics achieved a degree of unity that would have been inconceivable in Europe. It was a unity grounded in a biblical sense of themselves as a chosen people, a people set apart.

As it happened, however, the sense of apartness, the conviction of chosenness, was the defining trait of all the religious peoples who went their way outside the American Protestant mainstream: of black Christians, of Jewish immigrants, of Shakers and Quakers, and, after the Scopes trial of 1925, of the Protestant fundamentalists of the Deep South.

By the time Mary Flannery O'Connor made her First Holy Communion, then, the Catholic child in America was being raised on a paradox. She belonged to the oldest, biggest, vastest church of them all. Yet she believed that her belonging made her unique. And her sense of uniqueness was a trait she shared, whether she realized it or not, with the believers who were least like herself.

She was six years old when she started at St. Vincent's Grammar School, also on Liberty Square in Savannah, seven when she made her First Communion at the cathedral next door.

Like most Catholic children, she was photographed on First Communion Day, and with her white-lace-trimmed dress, her hair swagged to the side, she looks like a typical Catholic girl of the time, but there is already an alien fierceness in her stare.

If she found the occasion remarkable she never said so in writing. "Stories of pious children tend to be false," she declared later on, and in her work she would steer clear of Catholic girlhood and its rituals and appurtenances, as if she had foreseen all the awful memoirs that would issue from other writers and taken a vow to write no such thing.

The one exception is the short story "A Temple of the Holy Ghost." This story, in which a child comes to grasp the significance of the Eucharist, is not overtly autobiographical, but the child in it, alone among the children in O'Connor's fiction, is a Catholic child, and the quandary the child in the story fights with, the deadly sin the story is meant to dramatize, is the one the author herself would spend all her life fighting.

The girl is an only child, bright and strong-minded. One weekend her two second cousins come from Mayville to stay at her house. They are "practically morons," in the child's estimation. Their names are Joanne and Suzanne, but they call themselves Temple One and Temple Two because asister at the convent school where they board, seeing them go, has told each of them not to forget that she is a Temple of the Holy Ghost. This means they are to behave themselves with boys.

Joanne and Suzanne want to meet boys, but there are no boys around. As the girls change out of their brown convent-school uniforms the child has a brainstorm: What about the Wilkins boys? The Wilkins boys have a car, and "'somebody said they were both going to be Church of God preachers because you don't have to know nothing to be one.'"

The boys come that evening to escort the girls to the fair. They bring a guitar and a harmonica, and as the girls sit on a swing and the child spies on them from behind some bushes, the boys serenade the girls with a song that sounds "half like a love song and half like a hymn." It is "The Old Rugged Cross."

The girls take a turn, singing in Latin, in "convent-trained voices," long and slow. Wendell Wilkins says that it must be "Jew singing." What a moron! the child thinks. It is the Tantum Ergo--the hymn sung during the Mass as the priest holds the Eucharist aloft for the people to adore. Everybody knows that.

Then, as the others set out for the fair, the child, left behind, begins to brood. Here the story turns inward, and the narrator's voice becomes tender and confidential, as though the reader is all alone with the child:

She went upstairs and paced the long bedroom with her hands locked together behind her back and her head thrust forward and an expression, fierce and dreamy both, on her face. She didn't turn on the electric light but let the darkness collect and make the room smaller and more private.

At regular intervals a light crossed the open window and threw shadows on the wall. She stopped and stood looking out over the dark slopes, past where the pond glinted silver, past the wall of woods to the speckled sky where a long finger of light was revolving up and around and away, searching the air as if it were hunting for the lost sun. It was the beacon light from the fair.

She could hear the distant sound of the calliope and she saw in her head all the tents raised up in a kind of gold sawdust light.

The child has been to the fair before, and now, seeing it in her mind's eye, she longs to be there, among the "faded looking pictures on the canvasof people in tights, with stiff stretched composed faces like the faces of the martyrs"--and now, in a way at once proud and pious, she longs to be a saint or a martyr herself. Sainthood is out, she reflects, because "she was a born liar and slothful and she sassed her mother" and "was eaten up with the sin of Pride, the worst one"--but she thinks "she could be a martyr if they killed her quick." She imagines herself in the Roman arena among the lions; she tries to pray, and finds herself thanking God that she doesn't belong to the Church of God.

The girls wake her with their laughter. At the fair, they have seen a fat man and a midget and a freak who strode from one side of the stage to the other, saying, "God made me thisaway and if you laugh He may strike you the same way. This is the way He wanted me to be and I ain't disputing His way. I'm showing you because I got to make the best of it."

The child, precocious though she is, doesn't understand, so the girls explain. The freak is a male and a female at once. They have seen it with their own eyes.

The child tries to sleep; and as she drifts off she can see the people gathered in the tent, dressed as for church, and hears the freak declaring each of them is a Temple of the Holy Ghost.

The fairgrounds like a Roman arena; the tent crowded as at a revival meeting; the freak testifying to God's ways--the fair is akin to a religious ritual. But religious how? That is always the question in O'Connor's work; and in its last few pages, the story comes to define religion in the South, grounded in the side-by-side lives of Catholics and Protestants and their odd likenesses in the mind of a child.

The next day, when the girls go back to the convent, the child tags along. The rite of Benediction is under way in the chapel when they arrive--the priest kneeling before the gold monstrance in which the Eucharist is exposed, the nuns in their habits singing the Tantum Ergo. The child goes in and kneels down, sensing that she is in the presence of God, and prays: "Hep me not to be so mean. Hep me not to give her so much sass. Hep me not to talk like I do." And as the Eucharist is upraised, in her imagination she sees the man at the fair and hears him say: "This is the way He wanted me to be."

She has had the meaning of the Eucharist dramatized for her, and has grasped a tenet of her faith for herself as though for the first time.

The theology behind this revelation is complex, but the Baltimore Catechism would have made it familiar to the child. The Eucharist is the Bodyof Christ, and it represents Christ's taking on of a frail human body and taking on of human suffering on the cross, reminding the child of the hermaphrodite, whose sufferings reduce her pride to piety. And the Eucharist reminds her of her apartness. Although many Protestant churches of the time celebrated a Eucharist of some kind, only Catholics believed Christ was actually present in the consecrated Communion wafer through a sacrifice whereby God became present to them in the Body of Christ so that they might know him directly by taking him into themselves.

There is more to the story, as if O'Connor grasped that someday it would be Catholicism, and not the freakish varieties of human nature, that would need explaining.

When the child leaves the convent, the story goes on, she has the meaning of the episode literally impressed upon her: "The big nun swooped down on her mischievously and nearly smothered her in the black habit, mashing the side of her face into the crucifix hitched onto her belt and then holding her off and looking at her with little periwinkle eyes."

During the drive home the child becomes "lost in thought." As she watches night fall outside the car window she sees the sun--"a huge red ball like an elevated Host drenched in blood"--streaking the sky red like a road in a hillbilly song. It is an image of God, and of the way to God, and an image of Protestantism and Catholicism reconciled on the horizon--but the image of the sun eucharistically looming over all, above and apart, suggests the pride the Catholic child is prone to, the deadliest sin of all.

"When I came back from Washington I worked wherever I could," Day recalled, "living in one furnished room after another, moving from the lower East Side to the upper East Side and then down again to the lower West Side. It was a bitterly cold winter and the rooms I lived in were never adequately heated. We were still at war, and it was the time of heatless Mondays and meatless Tuesdays. There were times when it was pleasanter to spend the night with friends rather than face an ugly sordid room."

She was living what she called a "wavering life." It lasted only a few months--the winter of 1918--but became crucial to the story later told about her. For that winter was the time she spent in the company of other striving young writers, and in Malcolm Cowley's Exile's Return, which would become the definitive memoir of the so-called Lost Generation, she was singled out as one of the wildest of the wild.

Her biographers usually consult Cowley's book just long enough toquote his remark about her as a girl "the gangsters admired" at the saloon because "she could drink them under the table." But his book offers as much insight into her wavering life as her own memoirs do.

The way he tells it, everybody in the Village was caught between contradictory ideals of how to live. They were parochial Greenwich Villagers yet insisted they were "citizens of the world." They pronounced themselves exiles from bourgeois society but yearned to speak for America. They were incurable city people who romanticized rural country life. They were populists, confident in the will of the people, yet fancied themselves an avant-garde.

Those ideals could not be reconciled, and when the war came, says Cowley, "people were suddenly forced to decide what kind of rebels they were"; and for Day the ensuing "war in bohemia" became a war in her own character, a war between a life of experience for its own sake and a life of the experience undertaken for the benefit of others.

She had spent the previous summer in the company of Mike Gold: socialist, journalist, sometime editor at The Call, and author, later on, of a novel called Jews Without Money. Together they roamed the shores of lower Manhattan and the beaches of Staten Island. They sat up all night in a coffee shop near City Hall talking about how to change the world. They befriended homeless men and brought them to his apartment, allowing them to sleep over. Once when she was sick he snuck into her boardinghouse (men were not allowed) with medicine and hot whiskey and spent the night tending to her at her bedside. They read Tolstoy together and agreed that the answer to her "religious instinct" was Tolstoyan religion, a "Christianity that dispensed with churches or a priesthood."

She was working for another socialist magazine, called The Liberator, but the thrill was gone. She rented an apartment on Macdougal Street, above the Provincetown Playhouse, and began to spend her evenings with the theater crowd, especially Eugene O'Neill, the playwright in residence, who was on the cusp of fame and on the rebound from a broken love affair. For a while they spent every evening together. Their place of rendezvous was a saloon on Sixth Avenue named the Golden Swan, which had a room in the back known as the Hell Hole. They would drink with friends till dawn, and then she would walk him to his apartment around the corner. By then he would be dead drunk and shivering with cold. Sometimes she would follow him in and warm him with her body, she recalled, holding him in her arms until he fell asleep, whereupon she would go home.

O'Neill was a lapsed Catholic, and Day thought of him as an Irish IvanKaramazov, who had rebelled against God and religion altogether. "If ever a man was haunted by death it was Gene," she later wrote. "Was it Gene himself or some friend of his who told me how he used to swim far out to sea when he lived at Provincetown and how he played with the idea of death in those deep waters in the ocean from which all life springs? But he never would have taken his life because he felt too keenly his own genius, his own vocation, his capacities as a writer to explore and bring to light those tragic deeps of life, the terror of man's fate."

The Hell Hole was a place to escape from the fate of mankind and the cares of life. There was talk of Marxism, but for Day the revolution had lost its spark, for there was no real solidarity between the immigrant poor, who drank to banish the misery of their oppression, and the show people from the Playhouse, who drank to fill the hole left in their lives when the theater was dark. Alcohol brought on a phony camaraderie, an illusion of human brotherhood: the time she brought a couple of homeless men to the saloon for a nightcap, the bartender shooed them out.

Yet in that setting O'Neill brought her to a "consciousness of God." Once they were good and drunk he would start reciting poetry, and Day was struck especially by his rendition of "The Hound of Heaven," by the Catholic convert Francis Thompson. The poem today is an especially dated piece of Victoriana, but its conceit still charms--that God snaps like a hound at the heels of the would-be believer, who will be able to outrun the hound of heaven only so long. "It is one of those poems that awaken the soul, recalls to it the fact that God is its destiny," Day explained later on.

O'Neill knew the poem by heart, all 182 lines of it. "I fled him, down the nights and down the days / I fled him, down the arches of the years," he declaimed. "I fled him, down the labyrinthine ways / Of my own mind; and in the midst of tears / I hid from him"--and it was as though the poem were speaking to her directly.

So it was that at dawn, going home, she found herself stopping at St. Joseph's Church on Sixth Avenue, not far from the Hell Hole, thinking it inevitable that "sooner or later I would have to pause in the mad rush of living and remember my first beginning and my last end."

The first Mass in those days was penitentially early--5 a.m.--and yet there were the working people of the neighborhood hastening toward the church. They clambered up the steps and past the big wooden doors. She did likewise: "What were they finding there? I seemed to feel the faith of those about me and I longed for their faith."

She knelt in a pew near the back and collected her thoughts. She was twenty-one years old. All her life she had been haunted by God. God was behind her. God loomed before her. Now she felt hounded toward Him, as though toward home; now she longed for an end to the wavering life in which she was caught.

St. Joseph's is the oldest Catholic church in Manhattan, low and square, with fieldstone walls, high white pillars, and a portico topped by a cross that stands out starkly against the sky. It is a kind of house blend of old and new, of city and country, of Catholic Europe and leatherstocking America.

Day will come to this church again and again in the next few years. Finally she will come to stay. She is a generation ahead of Merton and Percy and O'Connor, and strides out ahead of them, the eldest and the most precocious, but what she will seek in the Church, and find in the Church, is what each of them will seek and find there: a place of pilgrimage, a home and a destination, where city and world meet, where the self encounters the other, where personal experience and the testimony of the ages can be reconciled.

For the time being, she began to pray. "Perhaps I asked even then, 'God, be merciful to me, a sinner.'" Perhaps she told herself, kneeling there, that "I would have to stop to think, to question my own position: 'What is man that Thou art mindful of him, O Lord?' What were we here for, what were we doing, what was the meaning of our lives?"

Copyright © 2003 by Paul Elie