1

ARTIFACTS

IN THE SUMMER of 1938, my grandparents David and Liza Kurtz sailed from New York to Europe for a six-week summer vacation. Together with three friends they visited England, France, Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, and, passing through Germany, they made a side trip to Poland, where both my grandparents were born.

I'm holding a postcard from this trip that my grandfather sent to his daughter, my aunt. The card shows a painting of the Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam crossing a green-black sea. Spray at the ship's waterline and whitecaps on the waves give the impression of motion. The black hull and white Art Deco superstructure gleam against clouds tinged with pink and blue. Smoke ribbons from twin yellow smokestacks. A bird trails off the stern.

On the reverse side, my grandfather writes, "On the boat five days. To-morrow we land at Plymouth, England, then Boulonge, France [he misspells Boulogne]—then Rotterdam, Holland. We get off at Rotterdam."

My aunt Shirley Kurtz Mandel produced this postcard three years after I first asked what she knew about her parents' 1938 trip to Europe. The manila envelope containing this and about thirty other postcards and letters from David and Liza had been stuffed in a box of unrelated papers, forgotten for more than half a century. Shirley rediscovered it in late 2011 when, after sixty-three years, she moved out of her New York apartment.

One year after my grandparents' vacation, Europe would be at war. On September 1, 1939, the German army overran Poland, and within a few years, with terribly few exceptions, the Jewish inhabitants of the Polish towns my grandparents had visited would be murdered.

But David and Liza Kurtz could not foresee the future. My grandparents and their friends were tourists, relatively prosperous American tourists, blissfully unaware of the catastrophe that lay just ahead. They rode across Europe with trunks of clothing, stayed at five-star hotels, shopped, and admired the sights. They visited art galleries and cathedrals, they strolled in the Jardin Exotique overlooking the old city of Monaco, they rode a small-gauge railroad through the Swiss Alps to the highest train station in Europe, the Jungfrau. Like tens of thousands of other Americans in the summer of 1938, my grandparents toured Europe's grand attractions for their own pleasure.

The postcard my grandfather sent to his daughter has an English one-pence postage stamp with the cancellation "Paquebot—Posted at Sea." It is postmarked Plymouth, Devon, 29 July 1938, 6:30 p.m. From this, I learn the date of my grandparents' departure, July 23, 1938, and that slender fact opens onto a wealth of period detail, giving me for the first time a glimpse at the scene as my grandparents begin their voyage.

"Rains Delay Sailing of Nieuw Amsterdam," reported the New York Times the day after their embarkation. "The Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam, under command of Captain Johannes Bijl, commodore of the line, sailed from her Hoboken pier forty minutes behind schedule after awaiting the arrival of four passengers from Philadelphia who had been delayed by a washout on the highway." The four Philadelphians, "all prominent socially," according to the Times, had called ahead from Plainfield, New Jersey, when the road north was "hidden by swirling water." The Nieuw Amsterdam was a stylish new ship. Its maiden voyage in May 1938, two months earlier, had been celebrated with lavish coverage in newspapers and magazines. This departure was less glamorous, the return leg of the ship's fourth round trip, but still worth a few column inches devoted to society gossip. A July 23 piece in the Times entitled "Ocean Travelers" noted that Mrs. Adam L. Gimbel, Mrs. Mary van Renssalaer Thayer, and Mr. and Mrs. John B. Ballantine would be among the 850 people on board when the ship finally sailed under cloudy skies that Saturday. The Washington Post considered it newsworthy to report "Mr. and Mrs. E. C. Rick will sail on the Nieuw Amsterdam this month for an extended tour in England, France, Switzerland and Italy. They will visit the Empire Exposition in Glasgow, Scotland, and later they will stop at Oxford to attend lectures at the university."

Mr. and Mrs. David Kurtz of Flatbush, Brooklyn, are not mentioned in the newspapers. They were comfortable but not prominent socially. Their travel plans concerned only the immediate family, and as a result, tracing their movements through Europe in the summer of 1938 has proved to be a challenge. I have been trying to determine their precise date of departure and the name of the ship for years. I know it now only because my aunt happened to save this postcard.

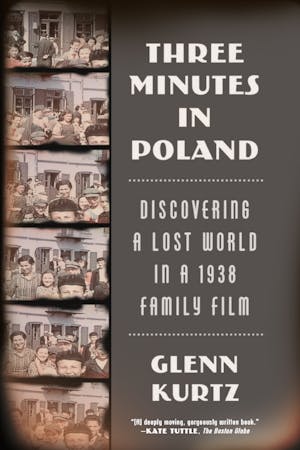

I would never have known about my grandparents' trip at all or felt compelled to spend years trying to unearth its details had David and Liza not brought home a unique memento of their travels, which also happened to survive. On this vacation, my grandfather carried a 16mm home movie camera. He shot fourteen minutes of black-and-white and Kodachrome color film. He captured scenes of the ocean crossing and of a ferry ride in Holland. He filmed my grandmother and their friends walking in the Grand Place in Brussels, sunning themselves on the Mediterranean coast near Cannes, feeding pigeons in a Parisian park. And he documented three minutes of their visit to Poland, footage of ordinary life in a small, predominantly Jewish town, one year before the outbreak of World War II.

More than seventy years later, these few minutes of my grandfather's home movie would transform their summer vacation into something of lasting, even of historical, significance. Through the brutal twists of history, my grandfather's travel souvenir became the only surviving film of this Polish town. Eventually, his home movie would become a memorial to its lost Jewish community and to the entire annihilated culture of Eastern European Judaism.

What moments are worth recording? Which stories and memories are passed down, and which are lost? How much detail is preserved in the few artifacts that happen to survive? And how close can these artifacts bring us to the people who left them behind? These questions have haunted and surprised me in the years since I discovered my grandfather's 1938 film.

* * *

The postcard my grandfather sent from the Nieuw Amsterdam at the start of this voyage is addressed to Shirley Kurtz at summer camp in Andes, New York. Above the ship, where the clouds are darkest gray and most roseate pink, David has written, "Thanks for the telegram." The telegram has not survived. My grandfather's message is only two sentences long. After briefing his daughter on their itinerary, he concludes, "Regards to the whole grand and to the Mirskys. Mother and Dad." My aunt Shirley, now ninety-two, was sixteen years old in July 1938. She has fond memories of Camp Oquago for girls, which had opened just a few years before and was in business until 1993. The Mirskys, she tells me, were the camp's owners. She remembers that Mr. Mirsky had a thick Yiddish accent. But she has no idea who or what "the whole grand" is. We puzzle over the word, trying to make it "gang" or "group" or "crowd." But it says "the whole grand." It might refer to a sports team or to her bunkmates at camp. It's possible my grandfather made a slip of the pen. We'll never know. Unlike the missing telegram, these words have been preserved. But their meaning is lost.

Taken by itself, it is a prosaic postcard, one of only a handful from my grandparents that has come down to me. Its value, like that of so many otherwise unimportant things, depends on context, on the scale of its information and the connections this enables us to forge, the snippet of a larger story it reveals. "On the boat five days." "We get off at Rotterdam." History is constructed from fragments like this, preserved by chance, puzzled over, connected. Because preservation alone is not enough. Every flea market and junk shop has shoe boxes full of postcards just like this one, with feathered edges and looping, half-legible script. All of them once carried messages woven into the fabric of individual lives. Now they're just atmospheric old postcards. With time, information and context tend to fray. Eventually they unravel completely.

* * *

I found the film of my grandparents' trip in the closet at my parents' house in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, in 2009. As soon as I saw what was captured in its images, I knew it had to be restored. My grandfather had filmed just a few minutes of one day in Poland. But this footage preserves impressions of daily life in a way that memory, photographs, and documents cannot. Viewing the film, we see hundreds of faces with individual expressions. We see the patterns and colors of dresses, a sign over a doorway, flowers in a shop window. We see the intricacies of small-town society in the groups that form on the street. We see the way a hand gesture or the peculiar set of someone's mouth or brow defines a personality or a relationship. We see the extraordinary pride of a young woman fortunate enough to accompany the American visitors during their brief tour of the town. We see the prevalence of shoving as a means of communication. If only for the sake of these details, I felt, the film was an important piece of history. It was evidence of a world violently destroyed.

But the longer I spent with my grandfather's film, the richer and more fragmentary its images became. A film, by itself, preserves detail without necessarily conveying knowledge. When I first viewed the footage, I saw hundreds of people, their manners and movements, the way they responded to my grandfather's camera and to each other. Yet each moment stood in isolation. The camera had recorded only the surfaces. Everything meaningful, everything that explained what I was seeing, existed outside or was buried inside the frame. Who are these people? What brought them to be on the street, in view of my grandfather's lens, on that day, in that moment? What relation, if any, do they have to my grandparents? And what became of them, each one, individually? Every image, every face, was a mystery.

I began to search, to research, to find out what might still be learned from this film and what, so many years later, might still be discovered about this town and its people. It's a challenge to reconstruct the history of ordinary lives. Ultimately, my search would absorb four years and would fling me across the United States, to Canada, England, Poland, Israel; into archives, homes, basements, film preservation laboratories, a grove of trees in a former Jewish cemetery, and an irrigation ditch at an abandoned Luftwaffe airfield—all to make sense of a few hundred feet of film. Yet in the end, chance—luck, or fate—played the biggest role in shaping this history.

Through a series of coincidences that in retrospect seem obvious, I met a man who appears in this film as a thirteen-year-old boy. He appears for a split second as my grandfather sweeps the camera past a crowd of children. This man lost everything in the Holocaust: his home, his family, his identity. But somehow he survived, and my grandfather's home movie survived, and seventy-three years after that moment captured on film, this man was able to view the film and, in some sense, to relive the moment. His recollections give voice to the silent figures in the film. My grandfather's film, he told me the first time we spoke, gave him back his childhood.

By circuitous paths, this man's memories would lead me to other survivors and to the families of some of those who did not survive. From among the hundreds of faces visible in my grandfather's film, the people I met would identify a few individuals they knew and remembered, some who lived through the war and many who did not, some who would have remained entirely unknown, and some who would have otherwise been faceless names on a document, nameless faces in an image. But more than this, the recollections that the survivors shared with me animated the images in my grandfather's film, fleshing out with stories many of the faces we see. From these stories, often from stray remarks made years apart, an intricate web of connections would eventually grow. Fragments of memory intersected with fragments of film, with fragments found in the few documents that still exist, in postcards, letters, photographs, and artifacts. And in the interconnections of these surviving fragments, I began to catch fleeting glimpses of the living town—a cruelly narrow sample of its relationships, contradictions, scandals. In this way, it became possible to save this small Jewish community, this shtetl, from the fate of so many others that were also destroyed and that have now succumbed to the one-dimensional tyranny of lists. Like my grandfather's film, the fragmentary history I assembled preserves a little of the town's vibrant complexity, the details that made its life and death distinct from others and made these people different from millions like them.

* * *

I smooth the fraying edges of my grandfather's postcard before placing it in an archival sleeve. Originally meant only for my aunt, this postcard is now a node in the intersecting stories that have grown out of my grandparents' 1938 vacation, stories defined in every part by improbable survival. My grandfather probably thought nothing of it when he posted this casual greeting. I'm certain he never imagined that a grandson, seventy-five years later, would read it with amazement, or that the information it contains, prosaic as it may be, would one day shed light on the life of a Polish town destroyed in the Holocaust.

So much about the story of my grandfather's film is untraceable. I'll never know how my grandparents felt as their ship pulled away from the pier and put out to sea. I'll never know what they experienced when they set foot in Poland again, forty-five years after emigrating to the United States. I'll never know what they thought once they returned to New York, or what they would have thought about the significance their trip and this film have since come to possess. But thanks to my aunt, I can now resolve one question that has long been a mystery to me. Although it turned up late in my search, this postcard allows me to document the start of my grandparents' journey, information recorded nowhere else. David and Liza Kurtz sailed from Hoboken on the Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam on a rainy Saturday afternoon, July 23, 1938, at 12:40 p.m., bound for Rotterdam. Now I know how the story begins.

* * *

I could also begin with my own journey, the moment I became interested in my grandparents' trip. It's a roundabout story that requires a brief detour into fiction.

In 2008, I was working on a novel set in Vienna, about two brothers, assimilated Jews, who escape from the city after the German invasion of Austria on March 12, 1938. I had lived in Vienna for several years in the 1980s, just after college, and I remained fascinated by the city and its history. On the seventieth anniversary of the Anschluss, I attended a lecture marking the occasion at the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York City.

The program that night featured a collection of amateur films documenting the German invasion, including a home movie by an anonymous cameraman that had been discovered recently in the Vienna flea market. By an extraordinary coincidence, this orphaned film contained unique footage of the harassment of Viennese Jews in the days following the Germans' triumphant arrival. The cameraman captured Hitler's motorcade driving down Vienna's famous Ringstrasse. In the film's final six seconds, a well-dressed man is forced to scrub the street on his hands and knees, a crowd of Viennese gleefully watching.

These so-called Reibpartien—"cleaning parties"—were a Viennese specialty. They were often instigated by neighbors and frequently noted in the press. A Time magazine article on March 28, 1938, entitled "Spring Cleaning," reported: "Hapless Jews were set to work scrubbing Fatherland Front posters off lampposts, Schuschnigg plebiscite slogans off sidewalks. Leering young Nazis jibed, ‘Who has found work for Jews? Adolf Hitler!'" The insightful British journalist G.E.R. Gedye wrote, "From my window I could watch for many days how they would arrest Jewish passers-by—generally doctors, lawyers or merchants, for they preferred their victims to belong to the better educated classes—and force them to scrub, polish and beat carpets…" A few iconic photographs document this form of harassment, but there were no known moving images. Then these six seconds of film were discovered.

After the program, I spoke with the presenter, Michael Loebenstein, who was then a researcher at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna and is now CEO at the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra, Australia. We subsequently became friends, and he kept me informed of his quest to identify the origin of this film. Analyzing frame by frame, Michael identified locations, retraced the cameraman's steps. He even determined the man's height by measuring the angle of certain shots. In April 2010, when we met again at the Film Museum café in Vienna just opposite the opera house, he announced, "I have managed from the most fleeting clues to establish who the person was who shot the film." It was a masterpiece of detective work, though still incomplete. "I know a lot about this person," Michael told me, "but I haven't got a name." He had also been unable to identify the victim of the harassment, and this in particular bothered him. "Usually, I'm quite good at separating my private emotional life and my professional life. But the thing about film is, on the one hand, it is such a technical medium, and on the other hand, it is something that touches you on the most fundamental human level."

Intrigued by this story, I decided to adapt it as the frame for my novel. A reel of old film lies forgotten in Vienna's flea market, I wrote, setting the scene on a cold March Saturday in 2005. The vendors have carted their wares back to wherever they store them during the week. Old coats, silver knives, vacuum cleaner parts, fake Gucci bags, the odd leather-bound copy of Mein Kampf. Now newspapers scrape the pavement and go airborne, folding and flapping as if they really knew how to fly. Hurrying across the square, Mara Reshen, the main character, absently plucks the film from the trash. Over the following pages, she becomes increasingly obsessed with the people in the film. Who are they? What became of them? Researching the images, she eventually uncovers the story of the two brothers and their attempt to escape the terror of Nazi Vienna. Are they still alive? she wonders. Could I return these moments to the people who lost them?

In the course of writing the novel, I had to learn about the chemical composition of film and about the condition issues a film from the 1930s would suffer, assuming it had been stored negligently. Motion picture film is made up of three distinct elements: the base, the gelatin emulsion, and a layer of color dyes for color film or metallic silver for black-and-white. The base is made of a heavy plastic—in the case of 16mm home movie film from the thirties and forties, cellulose diacetate. This is a moderately stable substance that will last for years under the right conditions, unlike 35mm nitrate stock from the same era, which is prone to disintegration and spontaneous combustion. But cellulose diacetate is susceptible to something called "vinegar syndrome." Over time, the plastic loses certain chemical compounds—primarily acetic acid, also known as vinegar—which causes it to shrink. Depending on how the film is wound and stored, this shrinkage will warp the base in different ways, and each kind of warp puts stress on the emulsion. It will crack, it will scratch, it will wrinkle. In the worst cases, the emulsion will detach from the base entirely. The emulsion carries the image. It's composed of gelatin, the same gelatin you eat, made of horse hooves, bones, proteins, a very nineteenth-century recipe. Because it is organic, the photographic emulsion will attract fungus and bacteria. These feed on the image. The emulsion may dissolve in water, expand or contract with humidity. It will collect dust and dirt. Color dyes fade, metallic silver corrodes. All of this degrades the quality of the images.

While reading about film preservation one day in September 2008, I remembered my family's small collection of home movies. I hadn't thought of these films in twenty-five years.

* * *

In my childhood house in Roslyn, Long Island, I knew exactly where our family films had been stored—in the den, in the cabinet beneath the television, alongside old cameras, slide carousels, and the portable transistor radios that no longer functioned. The stack of brown, silver, and black film cans was in the back of the cabinet, in the dark recesses, and I must have reached past them every time I rummaged around there as a kid, fingering the ancient gadgets that had so many attractive knobs, dials, and meters.

All our old photographic equipment was sold off in 1990 during the great deaccessioning that occurred when my parents retired to Florida. My father was not a sentimental man when it came to possessions. He tore the photographs from my grandparents' passports and tossed away the pages of visas and stamps. He discarded almost everything in the basement, all the junk in the closets and cabinets.

In September 2008, suddenly curious, I called my parents to ask whether our family films still existed. My father thought they must have been thrown away. A month later, I flew down to Florida from New York and hunted in the recesses of new closets, these, too, by now overstuffed with things. It wasn't until my third attempt, in March 2009, that I succeeded in locating the old stack of film cans in an unlabeled cardboard box in my parents' closet, behind the Scrabble and Monopoly boxes, beneath unbuilt model airplane kits.

There was a film of my parents' wedding in 1952; film from their honeymoon in Mexico City; films of my brother Roger as a baby learning to crawl, pestering Duchess, the dog. There were home movies of my father's sister, my aunt Shirley, and her son. Film of my grandparents at a summer house in Long Beach. Film of my grandparents' 1938 trip to Europe. They all reeked of vinegar.

I was still working on my novel, describing Mara's growing obsession with the enigmatic silent images in the abandoned film she had discovered. I worked on that book of fiction for another two years, until the story I had imagined happened to me.

* * *

The vinegary film I discovered in my parents' closet had deteriorated so severely it could not be projected. It had shrunk, curled on itself, and fused into a single, hockey puck–like mass. In any case, we no longer had a projector. In the early 1980s, however, some of the footage had been transferred to videotape, probably the last time anyone had viewed it. I found the cassette in a drawer at my parents' house and brought it home with me, along with the film in its dented aluminum can. In March 2009, I stood in the living room of my New York City apartment, the VCR remote control in my hand. I pressed the button, and my grandparents' voyage began again.

OUR TRIP TO HOLLAND BELGIUM POLAND SWITZERLAND FRANCE AND ENGLAND. 1938. The image wobbled and cracked, like a pane of glass breaking over and over. Then I saw Liza Kurtz, my grandmother, lounging on a deck chair on board what I now know is the Nieuw Amsterdam, sometime between July 23 and July 30, 1938. She's a dark-haired, regal woman in her late forties and wears oval sunglasses, a plaid blazer, and a matching hat. She has a thick book in her lap. The bookmark's tassel twirls in the wind.

Sitting next to her are my grandparents' friends and traveling companions, Louis and Lillian "Rosie" Malina, and Mr. Malina's sister, Essie, who had married my grandfather's uncle, David Diamond. Louis is sitting at the end of the row of chairs, reading. Between him and my grandmother, the other two women are asleep.

Liza looks up. Maybe David calls to her. Smile for the camera. My grandmother does not smile. A few seconds later, my grandfather shifts position. Louis keeps reading his book. The two sleeping women remain asleep. But in this shot my grandmother smiles for the camera, after first turning away to adjust her hat.

Suddenly they've arrived in Holland. There are people with wooden shoes and winged white hats. My grandmother coaxes a little girl in costume to wave for the camera. Essie and Louis stand beneath a hand-painted sign advertising a café-restaurant with a "vue sur la mer." Louis and the three women walk along a gravel path in a garden or park. They come down the steps of an imposing building. In the background stands a doorman or guard, the buttons on his uniform catching the light. They're no longer in Holland. Perhaps they're in Belgium. There are no obvious landmarks.

The film jumps around, a series of scenes in black-and-white, then a segment in brilliant color. They're on a boat crossing a tranquil blue lake. It must be Switzerland because soon they're in the mountains, my grandfather clearly impressed by the peaks and glaciers. He angles the camera down a thousand-foot waterfall beside the train. In the next shot, the waterfall is in a valley far below them. The Hotel Jungfrau stands in the foreground. My grandfather pans across the mountaintops.

Now Louis, a cigar in his mouth, gazes at a palace with a red roof, situated on a promontory overlooking the sea. It must be the Mediterranean, southern France. For fifty-one seconds they admire the coastline. My grandmother helps Essie tie her sunbonnet. For thirteen seconds they walk beside bright pink flowers planted beneath tall windows. Are they still in France? In England? Rosie Malina is laughing. My grandmother points past where my grandfather is standing and speaks to him. It seems she's telling him to film something else, to film over there.

The final minute of footage documents the journey home. Walking four abreast, Liza, Essie, Louis, and Rosie promenade along an enclosed deck. A sailor or steward follows them with his eyes. A square, numberless clock above their heads shows that it's just past seven. A few moments later, the three women stand behind a window, the ocean reflected in the glass, waves rippling across their faces.

The voyage is almost over. The ship enters New York Harbor. My grandfather's gaze lingers on the Statue of Liberty. As they steam up the Hudson, he pans south across the skyline on a bright late-summer day. The Empire State Building, the Woolworth Building, the oddly sparse profile of lower Manhattan. Then, with the Palisades passing behind them, the five travelers step in front of the camera one by one. Essie, in a red coat with a fur collar, wears a beret with a pom-pom on top. For six seconds she points steadily at something ahead, looking serious, slightly ill at ease. Louis, round-faced and dapper in his dark gray double-breasted suit, a white handkerchief in his left breast pocket, raises his hand in a kind of salute, touching his fingers to his forehead, then waving at my grandfather. Rosie, in a black dress, black gloves, black hat, squints into the sunshine. She's a small woman, and the wind flutters her dress and seems about to knock her over. Like her sister-in-law, she points a finger insistently at something behind my grandfather for the five seconds she's on-screen. My grandmother is next. She's wearing a black sombrero-style hat and a belted tan overcoat with mounds of fur on the shoulders. A red rose is pinned to her lapel. She walks directly toward the camera and flashes a radiant smile. Finally, for the only time, my grandfather appears. He's wearing a gray suit and a short, red-accented tie that wants to free itself in the breeze. The front flap of his jacket is folded under, making him look slightly disheveled. He says something, sweeps his finger across the horizon, then singles out a spot to emphasize. Maybe he's comparing New York to the European cities they've just visited. Maybe he's indicating the direction to their home in Brooklyn. The final frames show the crowd on the pier in New York, white hats and gray suits, upraised arms greeting the ship's arrival.

* * *

My grandfather shot a tourist film intended solely for the family. Almost every scene features someone waving to the camera or waving the camera away. The image shakes; the lens moves too quickly. This is what you expect from a novice cameraman traveling with his wife and close friends. See? he seems to say. We're here.

But when I watched this film for the first time, standing in my living room in March 2009, my fingers tightened around the VCR remote. Mixed in with the tourist shots, after a park in Belgium and before the mountains of Switzerland, were three minutes of my grandparents' visit to Poland. Three minutes of a fourteen-minute film. Three minutes, mostly in color, showing a vibrant Jewish community in the summer of 1938, one year before the war, just three months before Kristallnacht. The instant these scenes appeared, everything else faded away.

This is what I saw: Perhaps a hundred people crowd the street in front of a black sedan. The children jump up and down, making faces. It's a silent film, but I can tell the kids are shouting. They run to remain in the frame as my grandfather pans across the building fronts. Adults linger in the background, clustered by open wooden doors. There are workers in torn shirts and religious men in long black overcoats. Some women wear kerchiefs; most are bareheaded. Many of the girls have fashionable bobs. In the background, my grandmother and Rosie Malina laugh at the commotion my grandfather and his home movie camera have created. My grandfather sweeps the lens across the crowd. He tries to film above the pulsing mob of children, but they push forward and jut their faces into the frame.

People rush into a building. The camera jumps. Now there's a long procession as people exit the building. It must be the synagogue. A lion is carved into an upper panel of the ten-foot-tall door. Louis Malina emerges, escorted by a man in a gray cap. A man in a black coat tries to free his arm from the grasp of another man, who shakes his fist. Twenty, fifty, perhaps seventy people exit, first men, then women. My grandmother wears a straw hat banded by what looks like fruit. Rosie Malina is next to her. A woman carrying a child follows. My grandmother says something to her over her shoulder.

Then they are indoors. The film is in color, but the lighting is very bad. People around a table are shadows, silhouettes. Red flowers stand in the window—lilies, I believe. The camera moves across the room. Curious onlookers gather outside and peer in the window. A man snatches the hat of the man in front of him and waves it in the air. Inside, an old woman, whose profile shows she's missing most of her teeth, laughs with the woman beside her.

On the street again. A boy leans in from the right side and grins excitedly. Hey, look! he must be saying. The images are suddenly crystalline, the colors sharp. My grandfather films the same façades as before, but now he focuses on the people, three rows of children with adults scattered around. A woman in a red, green, and black dress has her arm on the shoulder of a girl with blond braids. The girl's dress has diagonal stripes. Another woman wears a black-and-white dress, the colors meeting in a zigzag across her chest. Two young men stand in the background, in black coats and black caps with short brims. One of them has a little beard. The other has his hand on his hip. A woman in a gray smock peeks from a storefront, views the scene, and retreats. The sign above her head is almost legible.

For forty seconds, my grandfather pans across the faces of schoolchildren, teenagers, adults, old men and women. They stand patiently, a little self-consciously, or they jostle each other. The girl with blond braids scoots sideways, keeping pace with the camera. An old man with a long white beard leans against a doorway. A girl with a bright red ribbon in her hair turns her head. A boy grins, exposing a gap between his front teeth. All of them gaze into the lens of my grandfather's camera.

Then we're outside a home. My grandmother comes down the steps, her arm held by a stately black-haired woman. Rosie Malina descends. Then Louis, accompanying a distinguished elderly man. A young woman bustles onto the stoop. She wears a white kerchief and a green dress with red piping at the neck and waist and on the edge of a pocket. She wags a finger menacingly at the children swarming her doorstep. A universal gesture, Go away! Scram! She takes Essie Diamond by the elbow and helps her down the stairs.

Three minutes. The scene ends. My grandparents continue their trip. They visit Switzerland and the south of France. They travel to Paris and on to London. They board the ship that will carry them home.

* * *

My father and my aunt were unanimous about the Polish town seen in the film: Berezne, they said, my grandmother's birthplace. Berezne, on the Polish-Ukrainian border, a shtetl with a population of about four thousand people, three thousand of whom were Jews. My aunt identified the Malinas and Essie Diamond, my grandparents' lifelong friends. Beyond that, she had only fragmentary recollections, passed down from her mother. "There were wooden sidewalks," Shirley said when we discussed the film on the phone. "There was a button factory."

I consulted my sister, Dana, the genealogist in the family. Dana is a whiz with databases. She easily found the U.S. Customs declaration documenting my grandparents' return from Europe. They had sailed from Southampton on August 31 on the RMS Queen Mary, which had set the transatlantic speed record earlier that summer. They arrived in New York on Labor Day, Monday, September 5, 1938, at nine thirty in the morning.

With the date, historical details were relatively easy to learn. There were 1,993 passengers aboard the Queen Mary when it docked that morning, a seasonal record for a westbound passage, according to the New York Times. Among them were the movie star Douglas Fairbanks and the stage actor Raymond Massey, who was preparing to play the title role in Abe Lincoln in Illinois on Broadway. Sir Henry Chilton, the British ambassador to Spain, was also on board. "Asked what he thought about the threats of war in Europe, the diplomat replied that they would be cleared up without hostilities." The Chicago Daily Tribune reported on September 6 that the Queen Mary had ferried $24 million worth of gold, the largest amount ever transported to New York on a single ship. The Christian Science Monitor dubbed it "a flight of capital from war-scared Europe." The following week, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, would visit Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden, seeking a political resolution to the crisis over the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. On September 30, Chamberlain, the master strategist of appeasement, returned triumphantly to London from the Munich Conference and waved a slip of paper above his head. "Peace for our time," he declared.

David and Liza Kurtz landed in New York as they had departed, unnoticed by the press. After a six-week tour of Europe, they filled out their customs declaration, then made their way home to their three children and to their comfortable, mostly anonymous life. The film of their summer vacation was sent to Rochester, New York, to be developed. I don't know when it returned, or whether my grandparents viewed it with their friends or their family. I don't know when it came to reside in a cabinet in my family's den in Roslyn. Indeed, when I first watched the film in March 2009, I didn't know anything about it at all.

In her genealogical files, however, Dana found a copy of a typewritten newsletter, the Babette Gazette, Volume 1, Number 1, dated May 21, 1939, Shirley Kurtz, Editor-in-Chief. The three-page paper records a meeting in Brooklyn of the descendants of Haskell Bab, or Babczuk, my grandmother's grandfather, a native of Berezne. The newsletter carried a feature by one of my grandmother's six sisters, Rose, "Childhood Days in Brezner." "On the West side of the house are two windows and on the north a door leading into the kitchen," Rose writes, describing the family home in Poland. "On the East side of the room is a door leading into a bedroom. This is the room that our Cousin Dave Kurtz mentioned in his speech. The room he tried to sleep in on his visit to Brezner. It is almost an historical room, at least to our family, for I and a few more in our family were born in this very room."

So Dana's family archive confirmed it: David and Liza Kurtz had visited Berezne—or Brezner, Berezno, Berëzno, Brezhna, —and had spent the night in the family home, sleeping in the room where my great-aunt Rose and my grandmother Liza were born. David gave a talk about the visit to a gathering of his wife's relatives in May 1939, almost a year after their trip.

That was what I learned from a few phone calls to my family. The formal history I gathered from the Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust and a little online searching: In September 1939, Berezne, located thirty-four miles northeast of Rovno (now Rivne), fell into the Soviet zone of occupation following the invasion and partition of Poland. The town was partially destroyed on July 6, 1941, two weeks after the German army attacked the Soviet Union. The German occupiers established a ghetto and a Judenrat, a Jewish council. On August 25, 1942, Berezne's Jewish inhabitants, along with other Jews from the surrounding area—a total of 3,400 people—were marched to a pit by the town cemetery and murdered by German and Ukrainian policemen with machine guns. Of the three thousand Jews who lived there in 1938, 150 survived the war.

Standing in my living room, playing the home movie again on my VCR, I realized my grandfather's three minutes of film might be the only moving images in existence of the town and its inhabitants prior to their destruction.

Copyright © 2014 by Glenn Kurtz