Book details

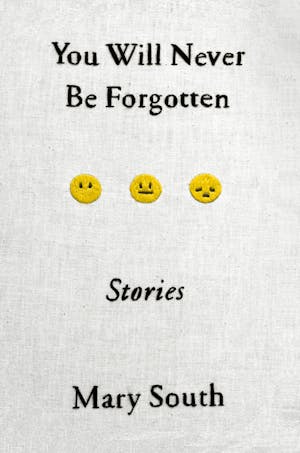

You Will Never Be Forgotten

Stories

Author: Mary South

You Will Never Be Forgotten

$15.00

You Will Never Be Forgotten

Author: Mary South

$15.00

Buy This Book From:

Reviews from Goodreads

About This Book

In this provocative, bitingly funny debut collection, people attempt to use technology to escape their uncontrollable feelings of grief or rage or despair, only to reveal their most flawed...

Book Details

In this provocative, bitingly funny debut collection, people attempt to use technology to escape their uncontrollable feelings of grief or rage or despair, only to reveal their most flawed and human selves

An architect draws questionable inspiration from her daughter’s birth defect. A content moderator for “the world’s biggest search engine,” who spends her days culling videos of beheadings and suicides, turns from stalking her rapist online to following him in real life. At a camp for recovering internet trolls, a sensitive misfit goes missing. A wounded mother raises the second incarnation of her child.

In You Will Never Be Forgotten, Mary South explores how technology can both collapse our relationships from within and provide opportunities for genuine connection. Formally inventive, darkly absurdist, savagely critical of the increasingly fraught cultural climates we inhabit, these ten stories also find hope in fleeting interactions and moments of tenderness. They reveal our grotesque selfishness and our intense need for love and acceptance, and the psychic pain that either shuts us off or allows us to discover our deepest reaches of empathy. This incendiary debut marks the arrival of a perceptive, idiosyncratic, instantly recognizable voice in fiction—one that could only belong to Mary South.

Imprint Publisher

FSG Originals

ISBN

9780374538361

In The News

Finalist, PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection

Longlisted for the Story Prize

New York Public Library, Best Books of 2020 • Electric Literature, Favorite Short Story Collections of 2020 • Literary Hub, Our 65 Favorite Books of the Year / Notable Story Collections of 2020

“Mary South couldn’t have predicted our current moment, but her stories could not feel timelier . . . Each of South’s self-contained, bleak and tightly wrought chapters centers on themes of isolation, loneliness and how screens aren’t just a constant presence in our daily interactions, they’re directing them . . . Her depictions of pregnancy and childbirth bring to mind a Margaret Atwood-esque darkness.” —Julie Bloom, The New York Times Book Review

“Written with dark humor and a striking lack of sentimentality . . . South’s precise, morally unburdened prose allows ample room for an exploration of the limitations of caregiving and the oft-futile human desire to rescue others.” —Jenessa Abrams, The Atlantic

"Imagine Black Mirror by way of Karen Russell and you’ll get a sense of this mordant and wondrous collection of short fiction." —O Magazine, Best Books of March 2020

“Prescient and unsettling . . . You Will Never Be Forgotten joins a growing cross-medium genre that includes Catherine Lacey’s The Answers, Ling Ma’s Severance, Russell T. Davies’s Years and Years, and the subtler episodes of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror . . . This collection’s power, though, comes from South’s dark sensibility, her comfort with brutality, and her narrative insistence that, while the nightmare of tech capitalism won’t wholly eradicate the personal and the private, it will compress beyond recognition the spaces where personal, private moments can unfold.” —Jennifer Schaffer, The Nation

“South’s vibrant collection is awash with zinging sentences, formal creativity, and conceptual verve. The writer both grounds her tales in precise contemporary detail and infuses her language with incredible imagination . . . South’s compassionate, quirky tales give us characters who wrestle with such contradictions in the most interesting ways.” —Alina Cohen, The Observer

"South’s inventive stories are funny and sad . . . These ethereal stories ['Realtor to the Damned' and 'Not Setsuko'] further consider what might have been in a life. In 'Realtor,' a man and his wife laugh at the odds and ends they discover in homes they will market. After his wife’s death, the forlorn Realtor, haunted now, receives calls from her cell number. The splendid 'Not Setsuko' . . . is equally touching." —Anthony Bukoski, Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A collection of ten dark and crystalline stories that announces the arrival of a distinct voice in contemporary fiction . . . The mordant wit and biting irony in You Will Never Be Forgotten, and its complex understanding of reality’s often cruel reversals, resonates with launching the book [in the time of COVID-19] . . . With most Americans confined indoors and spending more and more hours in front of our screens, there is value in a story collection that makes us stop and question just what these screens have wrought in our lives.” —Zack Ravas, Zyzzyva

"Edgily brilliant . . . Bringing together emotion and technology, South’s stories are comfortless but very sharp." —Phil Baker, The Sunday Times (London)

"[Mary South is] an impressive writer . . . The recognition or ignorance of mortality is a source of weird and wondrous humor throughout these stories as South throws different generations onstage and watches them wrestle it out . . . While we reckon with the loss of loved ones, lifestyles, and visions of our own immortal selves, the ghostliness of longing is an authentic experience indeed." —Cecily Berberat, Epiphany

"These highly contemporary short stories explore how we use technology to avoid our own feelings . . . South is one to watch." —Jessie Thompson, Evening Standard

“Mary South skillfully crafts narratives of emotional isolation. Both ominously bleak and shrewdly humorous, South constructs near-future worlds filled with sad and lonely characters . . . You Will Never Be Forgotten is a collection of stories reflecting the zeitgeist: melancholy dread in conflict with modernity. Her narrative voice is sharp, witty, and efficient.” —Ian MacAllen, Chicago Review of Books

"These stories are about tech-enabled delusion, dread and self-soothing . . . There is a lot of merit in good, inventively-crafted stories about murky tech, especially when they are peppered with Easter eggs of humanity and connection—think the best Black Mirror episodes." —Marta Bausells, Literary Hub

"A delightful opportunity to be as unsettled by your literary fiction as you are by your news feed . . . South’s prose is funny, propulsive, and completely original . . . South’s protagonists try time and again to abate their sense of isolation by seeking out increasingly invasive technological fixes, even though the isolation stems from forces completely beyond their control. Sound familiar?" —Eva Dunsky, Columbia Journal

"A mix of surrealism, science fiction, realism and magical realism, these stories remain grounded in human experience regardless of their genre-blurring tendencies. You Will Never Be Forgotten holds firmly together as an exploration of a modern moment defined by cutting-edge science and technology but nevertheless essentially comprised of human emotion. The writing, like the worlds in which South's characters live, is cool, hard-edged and sterile, but full of feeling." —Alice Martin, Shelf Awareness

“Curiouser and curiouser—that’s the name of Mary South’s game . . . Whatever might be dark about these stories may also be—since they’re reliably witty and frequently very funny—a welcome distraction and relief from current events.” —Drew Hart, Arts Fuse

"Playful, astute . . . South’s stories are both funny and profound, often on the same page, but perhaps her best skill is plumbing the intricacies of loneliness, expertly dissecting what that term means in a technology-driven world. This is an electric jolt from a very talented writer." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"In the standout pieces, the characters' pain is deeply human and affecting . . . [The title story] takes many brilliant twists and turns and culminates in an ending so surprising and inevitable Flannery O'Connor would surely approve." —Kirkus

"Appearing at first to be about the double-edged sword of technology, the collection is actually about people confronting their all-too-human emotions . . . At her best, South is reminiscent of George Saunders, replete with strangeness and dark humor. This intriguing collection should put South on readers' radars and is perfect for fans of Black Mirror." —Kathy Sexton, Booklist

"Mary South’s You Will Never Be Forgotten is one of the most luminous, funny, totally thought-provoking story collections I have ever read. Don’t miss it." —Douglas Stuart, Booker Prize-winning author of Shuggie Bain

"Mary South gets it. With dark humor, she knocks down like so many lined-up ducks all the consoling pieties that nurture humanist fiction, and sets up in their place a vision of subjects irremediably mediated, strung out along networks that far exceed them. Her universe is glitchy, full of weakly-encrypted memory, open-source desire, self-replicating fantasy: the human in hock to the algorithm." —Tom McCarthy, author of Satin Island

"Mary South's stories are a vital mix of wry humor, cunning provocation, disturbing prophecy and deep feeling. A brilliant and brilliantly strange and strangely funny and menacing debut!" —Sam Lipsyte, author of Hark

"Mary South's wickedly, exquisitely hilarious collection dwells in the intimate aches of modern life, writ large in strange, delightful stories that include, but are not limited to, clones, brain surgery, internet trolls, and warehouses full of spare men. Dazzlingly imagined and full of wit, You Will Never Be Forgotten is a gift to readers everywhere, a ferocious transmission from one of the most audacious, most original new voices in fiction." —Alexandra Kleeman, author of Intimations

“These swift and spiky stories dive, unafraid, into grief and violence—and emerge with insights as vivid and powerful as a lightning strike. You Will Never Be Forgotten is an arresting, unpredictable, and hilarious collection, and Mary South is an ingenious new talent.” —Laura van den Berg, author of The Third Hotel

"While Mary South's stories feature the cutting-edge technology of our present and near future, what makes this collection so exceptional is the deft hand with which she can peel back the sheen of novelty to get to the core of these characters' triumphs and struggles. With sharp insight and wit, South lays bare the timeless truths of love, loss and loneliness at the heart of these stories." —Sara Novic, author of Girl at War

"One of the strangest and most exciting collections I've read in recent times. This is what I hope for from speculative fiction: an unease that pulls you through the story with urgency, but also delivers new formations of haunting questions that linger long after the story ends." —Jac Jemc, author of The Grip of It

“This is a delicious, absurdly sharp collection of stories—funny, painful, macabre, sometimes gruesome, and humming with intelligence. Mary South is a tremendous talent and this book is a gem.” —Lydia Kiesling, author of Golden State

"What a heady, delicious, devastating collection. These stories, in their limitless wit and invention, begin as satisfying intellectual puzzles and then bloom into something fiercer, wilder—expanding to contain the fullness of dread, loss, longing, shame, terror. Mary South has written a tremendous book." —Clare Beams, author of The Illness Lesson

"Here are ten stories of loneliness and loss, bristling with gallows humor, and wrought of nimble, gleefully exacting sentences. With wide-reaching curiosity and deadpan wit, Mary South writes the absurdity and banality of technology-damaged life." —Kathryn Scanlan, author of Aug 9-Fog

About the Creators

You Will Never Be Forgotten

$15.00

You Will Never Be Forgotten

Author: Mary South