Picture a living room, a staging area. Furniture ringed around its perimeter—a large couch, several upholstered armchairs, a wooden accent chair in the corner. Big, demonstrative windows on the wall facing the street. A coffee table occupied the center of the room at one point, though it’s been removed: there are still faint indentations in the cream-colored carpet where the feet sat for years, and a rectangular patch of the carpet slightly richer in color. The center of the room, as a result of its former presence, seems eerily empty, anticipatory in its emptiness. There are two, maybe three entrances to the living room: it may open into a kitchen, or a hallway, or a foyer. Though there isn’t a television, the couch and chairs are arranged in a way suggesting there once was one, or there was clearly a focal point to the room, some space to which the eyes and attention of the sitters or those present were naturally drawn, as to an altar. This space has since been filled, maybe by bookshelves or a console table, another set of chairs, but the position of the other furniture still seems to cater to it—an angle toward which everything seems to lean, as if cocked at attention. The front window, curtains drawn, from the right angle offers a sightline clear to the house across the street, a brief, golden shot into a similarly made-up living room, reflected darkly back.

Out and beyond, over a land equally haunted, we settle like a smoke cloud, like breath in the palm of a hand, like the blood pounding in your ears in the instant after a shock, when your instincts are wild and uncalibrated, your body wracked, for a moment, with violent potential—like air boding a storm.

Inside, in one of these houses, one floor above, a bitter young man lies in his bed at the end of his day, his idle dark thoughts unspooling into the night. He is otherwise alone in the house, or effectively alone. His parents—in this case, a mother whose work has taken her elsewhere, and a father he hasn’t seen in a decade—are not part of this story.

Let’s begin here.

BY THE THROAT

The route to Sarah was easy, or should have been, because she spent a lot of time at Beth’s house, and Beth had a spooky older brother named Greg who was into serial killers and chokeholds and shit, so he had a lot of contact and had laid a lot of groundwork without knowing it, well before our arrival. Like he’d drift by Beth’s bedroom where she and Sarah were hanging out and linger in the doorway, and when Beth wasn’t looking he’d blink and show Sarah he’d painted a set of eyes on his eyelids, or he would pull up his sleeve to reveal the patterns he’d cut into his arm, or would be mumbling what sounded like occult prayers when the three of them got into his car in the morning on the way to school. There was no consistency to it whatsoever; the idea was basically to project that there was some secret regimen of behaviors that Greg adhered to out of spiritual or small-group obligation (the nature of the obligation wasn’t as important as the strength of his dedication to it), and for a kid who mostly just hid in his room consuming fringy internet-era media and coming up with ways to alienate people/himself, this was a pretty easy thing to do. Greg didn’t have the context for this at the time, of course—he was just being himself, and his behavior was just that, teen routine—but in retrospect, after the fact, these were the shapes it had, that we gave it.

Sarah took note: it was practically ingrained in her. She was carefree with her attention and love, and only had to hear about someone’s misfortune or depression before she hurled herself wholeheartedly into it—her passion and talent was for Being There—until whatever problem became hers as well, impressively hers, so bone-deep ran this empathy. She was the sort of person to whom, no matter how well you knew her, you could express the slightest sadness or upset and she would commit hours to talking it through with you, her time and warmth and attention would pool up around you until the problem had disintegrated within it. To those who liked her, Sarah was a girl of boundless enthusiasm and an open heart, a book that wanted to be read. To those who didn’t, she was a dilettante, a passionate fool. She had brown hair that curled more the longer it got, and was a beautiful soul. She seemed like the kind of girl who could be convinced to join a cult. She fell for it, of course.

She started by asking Beth, whom we hadn’t gotten to yet, either, and while Beth agreed Greg was weird, as she always had, it was in a sisterly way and thus wasn’t systematized. Sarah bounced from person to person in this manner until she talked to Claire, who herself was an agent of the dark and had, truth be told, her own separate agenda that was as yet unconnected to ours. “Yeah,” Claire said, skimming her eyes over the long line of cars waiting to exit the parking lot. It was second lunch period, when sophomores and juniors ate, and they were outside Adena High. The unlikely bond between the two of them had formed over a shared and wicked love of mid-2000s pop punk, which Sarah had developed before they were friendly but after she learned of Claire’s interest in such music, so she was genuinely passionate about it but the passion had a larger goal; anyway, Claire said, “Do you know anything about Half Blessed?”

“I think I’ve heard the name,” Sarah said, which was typically how she engaged with Claire’s expansive cultural milieu. Claire at present had a shaggy Chelsea haircut that was dyed blue, and wore a seasonal leather jacket whose pins changed daily, which lent her the kind of standoffish wisdom of someone who inhabits multiple eras. Had you asked Claire, at this point, she wouldn’t have called her and Sarah “friends,” exactly, nor would she have admitted that her love for pop punk—a genre she had never experienced in its contemporary moment—was anything but ironic. “Is that like a band?” Sarah said.

“I guess it was a band after the fact”—another common answer, there was always an obscure band buried somewhere—“but it’s more of a belief system,” Claire said.

“A belief system? Like some kind of religious thing?”

Claire shrugged. “I mean, as much as you’d consider iconography ‘religious.’” (She used air quotes.) “You’d see plenty of inverted crosses and whatnot but they’re not exactly burning churches, not in this decade anyway.” She paused and bit her lip, seeming to consider. “I guess it’s more of a society, is how they would put it, with some magical overtones. Basically teenage illuminati, but more social, like about ostracizing and status-climbing. Or like they’ll squat your house and slaughter a pig in the living room, blind fires, stuff like that. Basically it’s just a clique but with secret handshakes, sex pacts, and blood rituals—to appeal to the high school crowd.”

Obviously Claire had lost sight of her answer to Sarah’s question long before the words had finished leaving her mouth, but the important thing was that she had created a context for Sarah’s future inquiries (Half Blessed was a group thing, stringent like a religion but not a religion) and, disregarding the rest, had pegged it with a few terms Sarah could use to propel her investigation further, namely “sex pacts and blood rituals,” something called “blind fires.” Was Greg a part of it? Was that what made him act the way he did? After their lunch period ended at 12:52 Claire drifted off to trigonometry (which she called “trigonometrics” in the spirit of complication) pretty much having forgotten everything she’d said, while Sarah crossed the school’s hypotenuse from the south to the west unit and climbed the stairs to her AP English class, where she embarked on further literary analysis and, similarly, traced dense passages of text for their older meanings. Coincidentally, for different reasons, during that same period, Beth’s older brother Greg spread a wide swath of his own blood across the stall door in one of the first-floor men’s bathrooms. If one was dedicated to the cause, they could have found some geometry in it (or “geometricates”), that the bathroom, the very stall, was directly one floor below the seat in English where Sarah sat. But no one was making those connections at this point.

* * *

But before there was Greg—or before Greg became wrapped up in our broader aims—there was David. David was closer to Sarah than most others by virtue of the fact that they had dated for a few heady months, and at the end of it Sarah had even floated the idea of applying to the same colleges the next year. After their split—nominally David’s doing, though Sarah had prompted the conversation—they remained superficially friends, because Sarah was committed to a strict pact of non-awkwardness (she was mature that way), meaning they stayed teetering on intimacy: if David ever texted or engaged her in any way, Sarah always responded, exhaustively. David harbored a quiet and largely unspoken desire for revenge, primarily because he’d felt totally out of his depth in the relationship, because while Sarah appeared to be ready for serious relationship commitment at sixteen, David was still deciding if he should take the SAT again or not this year; he felt his concerns were shallow by comparison, and he resented it. In the months since their breakup last fall, he had been spending more and more of his time on YouTube, drifting quickly through the topsoil of self-improvement and wellness videos into the caverns of crypto-fascist pseudoscience and conspiracy theories catered to his exact demographic. By the time spring came, he was susceptible, his head filled with self-righteous garbage. David was where we started. He was an easy sell. He was also blessed in that he had a sick-ass basement.

So the Monday after we found him, an angsty day at the end of March, David texted Sarah, “Time to talk?” and Sarah replied with no fewer than two exclamations and three questions, saying effectively, yes, absolutely. David, adrenaline running high at the effusiveness of her response, customarily answered one of those questions, and that afternoon they met at Sarah’s house after school. They went up to her bedroom because they weren’t adults yet and the living room seemed like too formal a place to talk, as if they were going to divide up land or furniture. David made a tactical decision and took the desk chair, Sarah sat on the bed. The walls had recently been painted a dusty blue to Sarah’s specifications, and the new color still felt untested, alien.

After a while David ran his hand through his unmanaged curly hair and said he’d had a lot on his mind lately, as if in apology for their lack of contact.

Sarah sensed an opportunity to help out, but she didn’t want to assume it was about her. “What is it?”

He fretted and swiveled back and forth in the chair, one sweaty hand clamped on the armrest. He was demonstrably nervous. Sarah thought about putting her mouth on the armrest after he’d gone. “I guess I’ve been hanging out with these people lately? We’ve been spending a lot of time together.”

“Which people? Like Collin and them?” David’s sporadic collection of stoner-y acquaintances; she never understood if they were properly friends, or merely around.

He looked confused. “No, like a group … It’s not really kids from Adena.”

“What kind of a group?”

“It’s kind of like a society. Like you have to pass these tests to get in, it’s pretty strict. But, Sarah”—she wasn’t used to him saying her name, thus the moment felt staged—“it’s so addicting, the atmosphere. You should come sometime.”

There was that word again, society. Sarah tried to ignore the fact that David’s other hand was resting absently on his crotch, as was his habit, an easy correction to make but she didn’t have the heart for that, not as friends. “What do you do there?” she asked.

He pushed himself up in the chair, let out a breath indicating to Sarah that he had prepared for this, he wanted to spill, and then David, groin in hand, told her exactly what they did.

Afterward, Sarah would reflect that David’s description was generally, tonally in line with what Claire had told her about Half Blessed, but that he didn’t say anything about the group’s structure or intent, nothing about the “society’s” rules or foundation or who was or could be a member, or how one joined. Instead, he focused on the acts, and in this you could tell where his brain was (somewhere near his hand), and also that he was totally making it up. And so David delivered into the space between the chair and the lower bed his set of images—the sexual exercises, the trials and performances for the group, the testing and matching, the shared fluids—and Sarah reacted to it, she crossed her legs and let him talk as she blushed furiously, as her skin crawled in embarrassment. She was used to a certain level of internet-derived morbidity from David, she’d seen glimpses of it, but in the months they’d dated, he had never talked like this. They had achieved a certain level of touch but no one had even mentioned sex, their relationship had been strangely prudish in that way, so as she sat there on the bed she felt distinctly two ways: (1) that David clearly had not accumulated any practical sexual experience since they’d broken up (she found herself relieved to know this), but he definitely had imagination, or at least a sordid browser history, and (2) in light of this imagination, she had probably dodged something weird and upsetting. But she let him say his piece, and when twenty minutes later he seemed to be expired of imagery she asked, as if the monologue hadn’t just taken place, “And what is it called, this group?” To which David replied with two more grossly combined words, “Burst Marrow.” He didn’t realize the unexpected relevance this term would carry in Sarah’s life.

There was no indication from David, going forward, of why he would have approached Sarah with this sex cult story rather than any of his other friends, what specific advice of hers he sought—he was not sophisticated enough a liar to foreground this. And maybe this, his fundamental honesty even while he poorly lied to her, while he projected these obvious sexual insecurities and not-so-hidden desires, maybe this lack of competent deceit was how they’d ended up dating.

Sarah thought of these generally positive traits as she listened to him. She realized that what he seemed to like about the group (that is, what aspects he chose to emphasize about a group that clearly did not exist) was ultimately quite basic—camaraderie, shared sexual enthusiasm, a boyish fascination with the macabre, a dense set of rules, trade secrets. If there ever was such a group, she thought, David would be the ideal member, it would be good for him. Sarah further realized that while she understood now what had first attracted her to him, his readability and easy-to-satisfy desires—even the hand-on-crotch thing, maybe that was a mark for him as well, that he acted the same in public as he did in private—David was definitely not dating material, and never had been. He was not unique among boys. If his speech was supposed to be an entreaty to her, to have sex with him or get back together or scare her or make her jealous, if it was supposed to make her leap to him—oh, David—then it was a ham-fisted attempt at best. By the end of their conversation the sexual tension on Sarah’s end had dissolved completely and left in its wake a puddle of tender feeling, as one has for a stray or cutely deformed animal. She pivoted from his awkward speech and asked David a series of generic, basic-competency questions about the group—how long had he been going? how many people were there? where did they meet?—which David was unable to answer effectively. She told him—feeling a bit like his mother as she said it—that if he truly enjoyed it, as long as no one was getting hurt and everything was consensual and safe (she was referring to STDs and protected sex here but at this point it didn’t matter if he understood), then it was probably fine to keep going. “I’m glad you felt you could talk to me about it,” she said, standing up.

Surprised, he stood as well, and Sarah noticed again the height advantage she had on him, how his Cavaliers T-shirt was a size too big, and his hair flopped down heavily over his left eye unsupervised, in want of cutting. He really was like a little boy. “I’m glad that we can still be friends,” she said. She awkwardly hugged him and clearly felt his erection, which he had talked himself into and which she gamely pretended not to notice. She wore her masks better than he did.

So David failed at his one job, and he and Sarah went their separate ways: David wandered aimlessly down her moneyed suburban street in the manner of one who murders his classmate in broad daylight and then turns up standing mildly in the parking lot an hour later, bloody knife still in hand, and Sarah locked the bedroom door, debated texting Beth, but instead retreated deeper into her bed, her inquiries effectively resolved (there were two separate weirdnesses, David and Greg, Burst Marrow and Half Blessed), and when she came she snorted into the pillow thinking about one of the acts David had described, where the group had two people sit naked back-to-back, unspeaking, and the exercise didn’t end until you’d guessed who the other person was by their breathing; you wrote their projected name down on a card in front of you (it was used later).

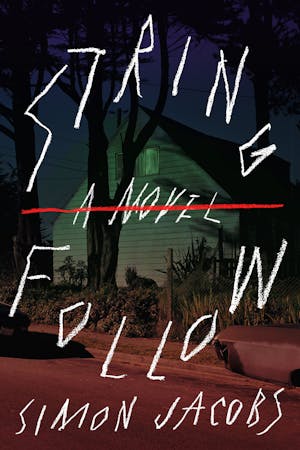

Copyright © 2022 by Simon Jacobs