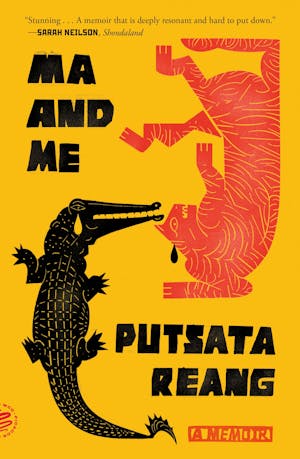

CROCODILE AND TIGER

There is a saying in Khmer, the language that left me in my youth but links me to a land across seas because it plinks off my mother’s tongue: “Joh duc, kapeur; laurng loeur, klah.” Go in the water, there’s the crocodile. Come up on land, there’s the tiger. Ma was twenty-two years old when she had to decide. The grandmothers in the village scolded her, “You’re too old. Your father is a drunk. No one will want to marry you.”

Being college-educated and unmarried at age twenty-two made my mother an anomaly twice over in rural Cambodia. Her mother married at fifteen; her older sister at eighteen. Matches made among elders. Her time was coming, she knew, but as she snuck past her teens and entered her twenties, she hoped to be forgotten.

The boys started coming around before she finished college. A simple village girl whose feet clapped across her dusty town in a pair of plastic flip-flops, my mother was raised by a benevolent uncle who deemed her brain too valuable to waste in the rice paddies. He told her, “When you get an education, you can do anything you want.” And she believed him.

These boys, the sons of professors and businessmen, followed her straight to her uncle’s door, begging to marry her. She wanted none of them. She wanted, instead, the thing that Khmer girls are not born to have or raised to want—dreams. She dreamed of becoming a businesswoman and traveling the country. Maybe even the world. She dreamed of living free.

But soon after she finished college, a rumor reached her ear. Her father, who had been mostly absent from her life, had arranged her marriage. He came around now that there was a profit to be made, when the dowry for his daughter might sustain more months of gambling and drinking. But Ma’s dreams were bigger than his greed. Before the invitations were sent, she fled.

She traveled east on a local bus that took her to Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, where she transferred to a regional taxi to Prey Veng province, on the eastern edge of Cambodia, mere miles from Vietnam. Her older brother lived there. He was sensible. He was kind. He would, she hoped, hide her.

But it was 1967, and that strip of earth along the Cambodia-Vietnam border shook and broke open beneath her feet when bombs from American B-52s burst in the paddies. The night sky lit up with machine-gun fire from the jungles, and she ran to the riverbed with her brother and his family, cupping her ears against the whistle of weapons, curling her body against the dirt somersaulting all around her.

A thought sprinted across her mind—I could die here. In the end, a part of her did. Along with an estimated 150,000 Cambodians. Casualties of a Western war imported to Vietnam, then stretched into Cambodia. “Collateral damage” was what the Americans said.

My mother realized she could stay with her brother and die trying to hide. Or, she could go back home and get married.

What do you do when you cannot go in the water or come up on land?

* * *

I was two when my mother taught me how to run and hide.

“Mouy, bee, bei … rort!” she would say. One, two, three … run!

Rort! Boern! Run! Hide!

And I would scoot off the sofa and skedaddle for a far corner or a closet or a bedcover and stay perfectly still. Rort boern. A game we played. I laughed and laughed when she found me, never successful in tricking her; she always knew where to look.

But then, one year later, another kind of running.

“Get down,” Ma said, hastily fastening her seat belt, eyes darting. “Keep quiet.”

She had woken us kids from our slumber and rushed us to the car.

“Like this?” I said, my body laid out on the back seat with my sister Chan.

She craned her neck to check the rearview mirror.

“Yes, gohn,” she said. “Lower.”

I rolled to the floorboard. My brother, Sope, was jumpy in his seat.

“Where are we going?” he asked, peering out the passenger-side window as our mother shoved the car’s gear into reverse and we shot, like a rocket, clear out of the driveway and into the lamplit stillness of our street.

“Nov aur sngeam!” she snapped, stay still, her voice starched with tension, struggling through her tears to shush her babies.

I felt the ridges of the plastic floorboard, cold and gritty, stamp their pattern into my cheek, and heard my own wheezing. Before she told us to duck, I had caught a glimpse of him, standing in the darkened doorway, hands on his hips, his lips spitting words I could not hear through the closed car window.

Copyright © 2022 by Putsata Reang