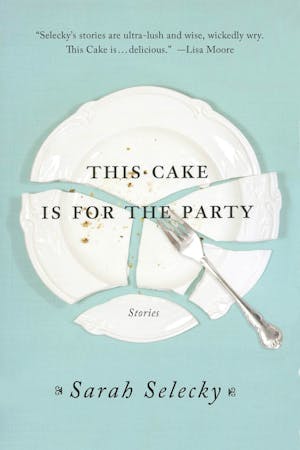

This Cake Is for the Party

Throwing Cotton

This past New Year's Eve, sitting on the loveseat in front of our little tabletop Christmas tree, I poured us both a glass of sparkling wine and told Sanderson: I think I'm ready to do it.

He kissed the top of my head and asked, Are you sure?

This is my last drink, I told him. I am officially preparing the womb.

Now it's the May long weekend. Sanderson and I have driven four hours north to Keewadin Lake, a cottage that we've rented every long weekend in May since we were at Trent together. We share it with our friends: Shona and Flip, who have been married even longer than we have, and Janine, who found the cottage for all of us almost ten years ago. I have a stack of first-year composition papers that still have to be marked, but I left them at home so this could be a real holiday. I have a strong feeling about this weekend. I think this might be the weekend we conceive. I'm trying not to get my hopes up, but my instincts are usually good.

We get to the cottage late, nine o'clock. It's already past dark and we're all very hungry. I can smell tension between Flip and Sanderson like something electric is burning. They both retreat to the living room. It's always been my job to sort the linens out when we arrive. But I feel particularly irritated that neither of our husbands has offered to help in the kitchen. These are progressive men. They know better than that. Shona and I move into the kitchen. Shona is an amazing cook, and she likes to do it.

Right in here, Shona says to me, even though I didn't ask her anything. She digs out a yellow packet of spaghetti from the bottom of one of the boxes. Told you! she says. She also finds a pot with a lid, a can opener, and cardboard tubes of salt and pepper left over from the last people who stayed here.

A knife, she says, distracted. Were we supposed to bring our own knives?

I remember the drawer from last year and show her.

I don't think they're very sharp, I say. We should have brought a good one.

This will work, Shona says, and selects one with a plastic handle and a pointy, upturned blade. It's not like we're carving a roast, she says. She starts slicing cloves of garlic on one of the speckled stoneware dishes. Each time the blade strikes the plate, the sharp sound makes me wince.

The sun was down by the time we got here. Now it's too dark to see anything. When I flick on the porch light, I disturb a fluster of moths. I cup my hands around my face and look out the window. There's a dock with a littlemotorboat tied to it and an apron-shaped beach. There is a pale glow that looks as if it's radiating from the sand.

The linen closet is where it always is, in the main hallway. I pull out musty-smelling sheets and threadbare pillowcases for both of the beds upstairs. For Janine's bed, on the main floor, I pick out the pink and orange flowered ones. Janine loves colour more than anyone I know. She's a graphic designer, but at Trent she studied English Lit like the rest of us. Not counting Sanderson, of course. She was actually enrolled in Sanderson's drawing class in her second year, but she withdrew when I told her I was sleeping with him. Those first years with Sanderson were more awkward than I like to remember. Our age difference was much more shocking when I was twenty-two years old. Now I'm teaching English at Ryerson and he's moved to the Art History department at York and I can't remember the last time I felt scandalous. I drop the flowered sheets off first, leave them folded on the edge of the mattress in her room.

She's not coming, Flip calls to me when he sees me there. Didn't she call you? I told her to call you.

She didn't call me. I hug my chest and follow his voice into the living room. I look back and forth between Flip and Sanderson. Janine didn't call, did she, Sand?

He shakes his head and fills his glass with more wine.

Did she say why?

She said she had a family thing.

I started dating Sanderson two semesters after I finished his class. I was the one who asked him out. We metin East City, across the river, at a small café not far from the Quaker Oats building. There was a woman wearing a red apron who served us coffee in thick white cups. I put two packets of sugar in my coffee and a long dollop of cream. He told me, You have a good eye. But you need to trust the line when you draw. He had silver strands of hair at his temples. I thought this made him look debonair and sophisticated. Now I think it's safe to say he's going grey.

I wish you wouldn't drink so much this weekend, I tell him.

We just got here, he says. It was a long drive.

Flip is stretched out on the chair, even though the chair itself doesn't recline. His body is slouched down so his seat reaches the edge of the cushion and his head is pressed into the back of the chair. His long legs are crossed at the ankles. It doesn't look comfortable. He takes up most of the living room.

I can tell you why she's not here, Sanderson says to me.

He rubs the side of his sandpaper face with one hand. He hasn't shaved for three days. He says the stubble makes him feel like he's having a more authentic cottage experience, so he cultivated it before we arrived. His beard is still dark--there's a patch of grey on his chin, but the rest of his face still grows a mix of dark reds and browns. Earlier this week, watching him sleep, I picked out the different colours sprouting. They grew like a pack of assorted wildflower seeds.

Janine feels threatened by your choice to have a child. She's withdrawing from you so she doesn't feel--He trails off.

Lonely and misguided, hopeless, bitter? Flip finishes for him.

Exactly, says Sanderson. She doesn't want to feel threatened.

Wait. My choice to have a child?

Flip ignores me. I can see now that he is stoned. But, but, he says. Janine must feel lonely and threatened already. Otherwise she'd be here, right? Whoa. I think that's a paradox.

Did she tell you that?

No, says Flip, looking at me again. I think it was her grandmother's birthday.

I glare at Sanderson. He looks pleased with himself.

The sound of the knife cutting on stoneware stops. I go back into the kitchen to open a bottle of seltzer. My choice to have a child. Okay. What I really want is a glass of red wine. Sanderson, of course, has the whole bottle next to his chair.

Shona hands me a glass from the cupboard above the sink. You want some lemon?

I want what you're having. I look at her glass of wine on the counter. But yes. Thank you. Lemon.

Shona is getting her master's degree at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto. She has told me stories about the kids she's working with in her practicum. For instance: There is aboy who is obsessed with chickens. He calls himself the Chicken Man. Occasionally he clucks to himself when he is drawing at his desk. When he's excited, he calls out, Chick-EN!

Shona has this quality. She observes the world more carefully than I do. She is slow to make decisions or judgments. She will listen to you ramble, and when you are finished, you feel like she has just told you something important about yourself. She is going to be a remarkable teacher. I hope that my son or daughter will be able to study with her.

Shona slices a lemon in half and squeezes it over my glass. Have lots, she says, it's cleansing. She rinses her hand under the tap, blots it with a dishcloth. Cloudy tendrils of lemon juice work their way into the water. I can hear the fizz of small bubbles rising and breaking the surface.

I look up. Did you know Janine couldn't come this weekend? I ask her.

Flip told me. Birthday party? Something.

I think it's strange. That she didn't call me.

Shona doesn't answer. She reaches up and pulls her ponytail apart to tighten it and I catch a whiff of lacy, pungent garlic. Her oval face with all the hair pulled back is like an olive.

I say, Sanderson says Janine got her dog because I decided to have a baby.

She was looking into the breeders before that.

Yes, but. She didn't actually get Winnie until after I told her.

And Sanderson thinks this is important.

I look into my glass and focus on the bubbles that cling to the sides.

There's never the perfect time to have kids, I say. Right? You just have to jump right in. You never feel one hundred percent.

You make a convincing case for it, Shona says.

Janine's latest project is a font that she's made entirely out of pubic hairs.

I'm still working on it, she said on the phone the last time I spoke to her. Parentheses were easy. But I need an ampersand. I haven't even done upper case yet.

I could hear a reedy whine from Winnie in the background. Then she said, I was sitting on the toilet one day and I saw a question mark on the tile by my foot. The most perfect question mark.

In your pubic hair, I said.

It's important for me to keep the letters genuine. I don't want to mess around with the natural curls.

Right. That would be missing the whole point.

No! Off! Mama's on the phone right now! Janine said. Anyway. I think it looks good. Almost Gothic, but still organic.

I wish that I could be more like Janine. She doesn't even pretend to care about anything other than herself, and we all love her anyway. I shouldn't be so surprised that she didn't call me about this weekend.

Wait a minute, Shona says in the kitchen, raising her wineglass and pointing at it with her other hand. Where's the rest of this? Is Sanderson hogging the wine?

In the living room, Flip and Sanderson have started to argue.

Sanderson leans forward in his chair in a half-lunge. His white sweatshirt has a logo with two crossed paddles on the chest, and a few spots of red wine that he won't notice until tomorrow morning.

Flip's face is tight. He says, If smokers came with their own private filtration systems, they could breathe what they exhale themselves. But we haven't invented that yet. So we stop smoking in bars.

Nobody's forcing you to breathe smoke.

Yes they are. In a bar, when there are smokers, it's everywhere.

Sanderson nods his head, leans back in the chair. Listen, he says. If I don't want to see a monster truck derby, I don't go to the arena. Get it?

You don't have to be an asshole.

You used to be a smoker too. I don't see where you get off.

Shona interrupts. Honey, leave it, you're stoned. Sanderson, pour me some wine.

Marijuana is different, Flip says.

They've been smoking in bars since the beginning of time, Sanderson mutters into his glass.

I don't like to see them fight like this. Sanderson thinks Flip needs to stop smoking dope--that it's making himdumb. Shona told me that Flip cringes when he reads Sanderson's emails because of the spelling errors. It's so important to each of them that the other appears intelligent. As though Sanderson's own intelligence is threatened when Flip appears dim-witted, or the other way around.

I get the bottle myself, since he's not making any move to do it. I pour some for Shona. Then I pour the remaining trickle into Flip's glass. Shona made dinner for us, I say, and turn to Sanderson. Say thank you.

Don't talk to me like I'm a child, he says. Then he flashes a wine-stained smile at her. Thank you, Shona.

There was a student in the fall semester. A young woman named Brianna. She's very bright, Sanderson told me. Her technique is rough, but inspired. Sanderson would call me in the afternoon, sometimes as late as five o'clock, to tell me that he was going to miss dinner. He never lied about where he was. He'd say they were going for drinks, grabbing a bite. He was helping her with her portfolio. One night he took her to Flip's bar. That's how self-assured he was. Flip told me that he saw them share a plate of calamari. That the woman fed him a ring from her fork. He said, The way she leaned across the table, Anne. I don't know.

I have always known this about Sanderson. He's one of those men who can keep his loving in separate compartments. He can love two women at once and not feel that he's betraying either of them. But when we got married, we promised that we'd tell each other about our attractions,that there wouldn't be any secret affairs. I can understand having a crush. It's lying about it that bothers me.

It's eleven o'clock when we sit down at the wobbly kitchen table to eat. The pasta should have been cooked for another five minutes. It sticks to my teeth like masking tape. But the four of us are so hungry we finish most of the noodles anyway, use up the whole pot of sauce to cover the piles on our plates. Flip mops up the last of it with a slice of garlic bread. Sanderson is quiet, possibly craving a cigarette. Shona is the only one who has wine left in her glass. I wrap my ankles and feet around the cold metal chair legs and silently will Sanderson to not open another bottle. It's cold in the cottage, even though the candles on the table make it look cozy. I could go put on some socks, but Sanderson already took my bag upstairs and I'm too lazy to go up there. My belly feels full and tight from too much pasta and bubbly water.

So, have you picked any good baby names? Flip asks me.

I heard someone in Calgary named her daughter Lexus, I answer.

I think it's exciting, Shona says. I'm living vicariously.

Flip looks at her. You want one too now?

This is how it happens, Sanderson says.

Shona looks at him. What exactly do you mean, she says.

We all want meaning in our lives. We all want to feel significant. Why else would we choose to have babies? It's our mortality thing.

Flip says, You have a mortality thing happening already?

Shut up, says Sanderson.

I try saying this out loud: I just think it's time. I feel ready. I don't want to wait until I'm old to have a baby. I want to be a cool mom.

Shona says, I hate to say this, sweetie, but I don't think a mom will ever seem cool to a teenager.

What do you think is old? Flip asks.

I just feel ready right now, I say.

Sanderson pushes his chair back from the table. He says, If I'm not ready now, I'll never be ready. It's time to throw cotton to the wind. He picks up his plate and brings it to the counter, plugs the drain, and turns on the hot water tap. Did we bring dish soap?

Shona points. Underneath.

Caution, I say.

What?

Everyone is quiet for a moment. Then a round, hollow, and breathy sound comes from Flip, who is trying to hide his laugh in his wineglass. It sounds like the fossilized call of a loon. Shona rolls her eyes at him.

It's throw caution to the wind, not cotton, I say.

You know what I mean. You don't have to make fun of me, he says.

No, it makes sense. You just throw cotton to the wind. It starts blowing around, right? Because of the wind? I start laughing, knowing that I should stop if I don't want to start another fight.

Sanderson ignores me. He looks in the cupboard under the sink and finds a bottle of green dishwashing detergent. He squirts some into the sink and there is a sweet apple smell. A white foam begins to grow on the water. Flip and I make ourselves stop laughing. We all sit at the table and watch Sanderson do the work.

You're going to quit smoking when the baby comes, right? Flip asks him.

Sanderson looks pained. Yes, Flip, of course I will.

Shona gathers the rest of the plates on the table and stacks them in front of her. She places the three forks on the top plate, which is covered with splotches of red sauce like a lurid Rorschach test. I think it would be nice, she says, for our babies to grow up together. She rests her hands on her belly.

Flip stares at her. I think we should wait, he says. Until you start teaching. You'll get maternity leave when you have a job. He touches his upper lip with his thumb. We could get a dog first.

Like Janine, says Sanderson.

Janine's dog is a baby replacement, Shona says. I want the real thing.

Flip holds the edge of the table with his hand. No, no. I'm way too irresponsible.

Shona sighs when she brings the stack of plates to the sink. You're just a scaredy-cat, she says. If I got pregnant, something would click for you. You'd get another job.

I say, What's wrong with working at a bar? Bartenders are respectable people.

You know what a baby means, says Flip. The money. There are those trust funds, those babies with the little graduation caps. No. Not until my own student loans are paid.

Shona laughs. Stop it, you're killing me. Paying off our student loans!

Sanderson turns off the tap and swishes the water with his hand. There's the bumping sound of plates swimming against stainless steel. Shona is beside him at the counter. She puts an arm around his waist and leans against him. He braces himself against the counter with one hand and holds her weight. Look at Sanderson, she says to Flip. He's not a scaredy-cat. I bet he still has student loans. Don't you, Sandy?

I glance down at my stomach, the way it makes a small ball of itself when I sit. It looks flat when I'm standing, but there's a little roll when I'm sitting down. I fix my posture in the chair. My belly changes when I straighten my back, but it still rests in a small lump on top of my legs. It's not a pregnant lump, it's just a weak abdomen, too much for dinner. But I try to imagine what it would feel like. When you're carrying a baby, you must feel like you're always carrying around a little Christmas present.

I'm actually all paid up, says Sanderson. But I had scholarships, so.

Flip stands up and fills my field of vision with his long legs, his green plaid torso. Sanderson is older than I am, he says. He's much more mature.

Don't you forget it, Sanderson says. Now excuse me, all of you, but I'm old, and I need a cigarette.

Don't turn on the porch light, I tell him. You'll attract the moths.

When he goes outside, I reach over the table for what's left of Shona's wine. Flip waggles his finger.

Oh, drink it, Shona tells me. It's not going to hurt anything. If Janine were here, you'd be drunk by now anyway.

This winter, when she bought a new condo downtown, Janine sent an email: I'm throwing a housewarming party. Just for us. Come at eight, stay till late. It was the coldest night in February, steam swirling on top of Lake Ontario because the air was so much colder than the water. When I blinked, my eyelashes stuck together, frozen. We arrived with housewarming gifts: a bottle of Tanqueray Ten, a jar of vermouth-soaked olives, a shiny silver martini shaker.

Janine opened the door and there was a gush of warm air in the hallway. The entranceway was a bright lacquer red. All along her wall, a line of tea lights glowing in glass saucers. She wore a short sequined cape on top of a black dress. It fell just above the elbows. A capelet. I felt the air melt around my body, my face defrosting. Janine had sparkles brushed along her cheekbones.

You brought cocktails! she said. She took the tall bottle out of my arms.

You look gorgeous, I said. I'll have a virgin cosmo.

Virgin my ass, she said.

Great paint job, I told her.

Like it? It's the same shade as Love That Red by Revlon. I had it specially blended and shipped from this place in Oregon.

It's hot, Sanderson said.

Inside, Flip and Shona were already drinking, sitting on chrome bar stools. Shona stirred pink juice in a glass with her finger. They were talking about the ways people learn. Shona had just come from class. She said, There are three ways that we all learn: we're either auditory, visual, or kinesthetic.

I'm visual. I know I'm visual, Janine said.

Shona said, We learn in all three ways, but we lean one way most of the time.

I went over it in my head: It's hot, Sanderson had said. He didn't say to her, You're hot. But that's what I heard. I had just come off the pill at that point. My hormones were still stabilizing.

I walked to the back window. There was a good view of the Gardiner Expressway. A string of red tail lights curved away from me, and the cars made small movements as they braked and accelerated. From this distance they looked like I imagined blood cells would look, moving through a capillary.

Flip came up behind me and said in my ear: Hello, I'm kinesthetic. What are you?

Sanderson was at the bar looking for a shot glass. Janine had filled the martini shaker with ice cubes. The bottom half of the shaker was already cold grey, frostingfrom the inside out. Her sequined cape, the martini shaker, the bar stools, Sanderson's hair: I turned around and saw everything in silver.

Janine said, You're visual too, Sandy. She flickered her fingers on his chest to illustrate her point. He wore a white T-shirt with a silk-screened drawing of a swing set on it.

I think I'm all three of them, I said. I can't just pick one.

Now Flip, he's auditory, Sanderson said.

And how would you know? Flip asked from across the room.

Because you talk so much.

Fuck you, said Flip.

Then, in a soft voice, Flip said to me, How are you doing.

I leaned into him. Ooh, I said. Is that velour?

Touch it, he said. I petted his sleeve like it was a puppy. His arm felt warm through the plush. I stopped at his wrist and held it with both of my hands.

Don't be mad at Sanderson, I said. He's just wired that way.

With the girls, you mean.

It's not serious with Brianna.

Well, good. As long as it's not serious.

I looked at him. We're human beings, I said. It's normal to flirt. We can't help being attracted.

Flip took his arm out of my hands. You don't have to explain it to me, he said.

I just love Weimaraners, I know, Janine was saying. She had brought a dog book out to the bar. She pressedthe spine open with the palm of her hand. But my space is so small, she said. What do you guys think about this one? Is he too cute? Would you laugh at me if I got a terrier?

We'll always laugh at you, darling, said Shona.

What kind of terrier? Flip asked.

It's called a Cairn terrier. And it's oh-my-god cute. But then I would be one of those women, wouldn't I? Janine made a face. She held a fresh Tanqueray martini. The glass caught the light from the halogens overhead. It glimmered in her hand. There were three olives speared on a silver pick.

Shona said, Janine, you're already one of those women. Don't fight it.

If you see me with a Burberry dog coat, okay? You have permission to smack me.

Can you make me one of those, I asked Sanderson. With onions if she's got them.

On the fridge door, middle shelf, Janine said. She smiled at me. Virgin.

You want one too, Flip? Sanderson said. I'm pouring.

Flip looked at him. I'm kinesthetic, he said. Read my body language.

That night in the cottage I dream about a blizzard. Janine and her dog Winnie are trying to dig something out of a snowdrift. When I wake up, it's still dark out, and Sanderson has stolen all of the covers. I'm freezing. I lean over, grab the pile of comforters and blankets on the floor beside him, and pull them over the bed evenly again. He'swearing the blue boxers I gave him for his birthday last year. He sleeps on his side, one arm under the pillow, the other stretched out in a straight line away from me, his hand almost touching the night table. His hand is curled as though it could be holding something very small, like a pinch of salt.

I flatten myself against him, wrap my body around his lower half. I lift up my T-shirt and press my breasts into his skin. Tease my hand over the front of his boxers. The skin on Sanderson's neck is damp and bristly against my lips. I promise God, the Universe, the baby itself: Please let me have you. I will love you like nothing else has been loved before. Sanderson exhales a sour cloud of undigested wine.

There's a sound downstairs. Outside, on the deck: soft thumps, like falling potatoes. I stop the prayer and hold myself perfectly still. A rustling against the glass, a bump against the kitchen doors. It sounds like someone is trying to break in.

I whisper Sanderson's name, grip his hip and shake it so that his whole body rocks the mattress. He makes a noise like he's slurping something through his mouth.

I wrap a fleece blanket around my shoulders and shuffle across the hallway and peek into Flip and Shona's doorway. Flip is sleeping on his stomach, face pushed into the pillow, facing Shona. Shona is splayed on her side like a pressed flower, arms and legs draped over Flip's body in the effortlessness of sleep. Now that I am fully awake, Ican hear the thumping sound for what it is: paws, jumping on the wood of the deck.

I go down the stairs slowly, starting on tiptoe and rolling to my heels so I won't scare them away. A family of raccoons. Three small ones rolling like bear cubs on top of one another. Close to the glass doors, a large raccoon--the mother, naturally I think it's the mother--sorts through the remains of the plastic Dominion bag that we used for garbage. The leftover spaghetti noodles seem to emit moonlight, making an elaborate pattern of loops and curls. I fold myself into the armchair and watch the little family make a huge mess. I look for letters in the patterns of noodles, try to spell out the letters in my name.

When Flip comes down, he sees me bent over in the chair with my face in my hands staring out the window.

Anne, he says. What's wrong? What's happening?

I look up at him. He has a T-shirt on, boxer shorts. His hair like a pile of twigs.

The raccoons got into our garbage.

He follows my gaze to the window. Shit, he says.

It's our own fault. We should have thought.

Flip rubs his head. You couldn't sleep either?

I just saw you. You were sound asleep.

I need a snack, he says, and goes into the kitchen.

The mother raccoon stops what she's doing for a moment and stands on her hind legs, her paws held in front of her. It looks like she's watching me. But I haven'tturned any lights on. It's perfectly dark, we're concealed in here.

Flip comes out with a plastic honey bear and a spoon. Scootch over, he says, and sits next to me, half on the seat cushion, half on the arm of the chair. He squeezes the honey bear over the spoon. There is a shine in the dark when the honey flows out. He slips the spoon into his mouth and closes his eyes.

Flip.

Mm?

Do you know something.

What.

No, I mean, do you know something that I don't know.

Have some, he says.

He fills the spoon again and brings it to my lips. He doesn't let go, even as I work my tongue over the spoon, licking all of the sweetness off it. Then he slides it out of my mouth.

There, he says. Is that better?

His bare leg touching mine on the chair. It could happen so easily.

You can tell me, I say. Janine and Sanderson. Am I right?

Oh, Anne, Flip says.

I won't tell him you said anything. I figured it out on my own. I just want to know for sure.

There's nothing between Janine and Sanderson.

If there's nothing, then why isn't she here this weekend?

Anne. She wanted to be here. It really was a family thing.

I stop talking. Flip is resting the honey bear on his knee. He plays with the pointy cone on top of its head with his index finger. Circles it first one way and then the other. When his finger gets too sticky, he puts it in his mouth. Looking at me as he does this. I feel my nipples tighten into hard French knots under my T-shirt. He leans over and drapes his arm around my shoulder. His face is very close to my face. I can breathe him. He smells like toasted bread and Ivory soap.

I let my head fall back so he can kiss me. I notice differences: the softness of his lower lip, the way he cups the side of my face in his hand. That his face is smooth, even at this time of night. It is the first time in nine years that I have kissed anyone but Sanderson.

There, he says, and pulls away from me. That's what I know.

My eyes have adjusted to the dark, but they take shortcuts, turn shadows into shapes. It's too dark to see anything clearly. The shapes adjust when I think about what I'm looking at differently. When I stare at Flip's shoulder, the darkness clusters in front of my eyes and I can turn it into a perfect sphere. It crawls with darkness and I think about what Flip's shoulder should look like and then it morphs into a shoulder again. I remember an old drawing lesson, something Sanderson told me years ago. When you're drawing an object, you need to stick to one viewpoint. Set the object down and sit so you can see it withoutmoving your head very much. You always want to have your head in the same place whenever you look at the object. A small movement can make a surprisingly big difference once you start drawing the details.

You should go to bed now, I say slowly.

Is that really what you want me to do?

Yes.

Fine, he says, and he pulls me off the chair and I go with him to the couch and we make love there. We move quietly and quickly. He says my name as he inhales. It sounds like and, and, and. When we're finished, we don't say anything. We lie on the couch together breathing honey. My arm is stuck in a crevice between the couch pillows. I feel something gritty rubbing against my elbow. Flip moves first. He slides his hands down along my hips and rests his head on my chest before he stands up. Then he goes upstairs and I can hear the water running for a minute.

I find my way into the kitchen and, without turning any lights on, I feel for a plastic bag in the drawer. I bring it outside onto the deck. The raccoons have pulled everything out and thrown it into piles. I crouch and scrape up the noodles with my hands. The wood looks stained even when the garbage is gone. I'm still in my bare feet. I know I should be cold, but I can't feel it.

THIS CAKE is FOR THE PARTY. Copyright © 2010 by Sarah Selecky. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.