ONE

Frida in the Wilderness

My biggest dream for a very long time has been to travel.

—FRIDA KAHLO, 1927

Frida Kahlo was a spontaneous woman who adored adventure, as long as it didn’t keep her away from home for too long. She was thrilled to realize her dream of traveling to San Francisco, but leaving her family and her homeland for the first time was monumental. There were many unknowns. What was San Francisco really like? Would she get along with Diego’s artist friends and their wives? Would she be able to communicate, given her poor command of English? Would she like the food? Would she be inspired to paint? Would Diego, her husband of fifteen months, be faithful? Would she?

In the short time she’d been married, Frida had found adjusting to Diego’s all-consuming painting schedule, late hours, chaotic lifestyle, and erratic moods challenging. Their life together was shaping up to be a syncopated rhythm with explosive accents. This was no surprise. From a young age Diego had possessed an intense energy that frightened his mother and charmed his father. He would harness this potent energy to fuel his prolific painting career, incite political brawls, and pit admiring women against one another. Frida was only beginning to feel the complexity of this man’s emotional needs—if she wasn’t a chain smoker at this point in her life, she would become one.

The long train trip to San Francisco offered Frida and Diego plenty of time together. Frida loved the ride, exclaiming, “The trip is wonderful because the train runs all along the coast, through Mazatlán, Tepic, Culiacán, etc., until it reaches Nogales, the U.S. border.”1 Although the United States created a borderline to demarcate two separate countries, it ended up being a place where two cultures gave birth to a third. Frida observed: “The damned border is a wire fence that separates Nogales Sonora from Nogales Arizona, but you could say it’s all the same. At the border, Mexicans speak English very well and gringos speak Spanish, and they all get mixed up.”2 Nevertheless, passports had to be checked on both sides and medical exams passed before they were allowed to continue north through Arizona and west toward the next major stop, Los Angeles.

In the City of Angels, they saw friends, met the art dealer Galka Scheyer, and took in the sights. They enjoyed the beaches, architecture, and movie stars’ homes, but Frida still had her criticisms:

The gringas are all hideous. The movie stars aren’t worth a damn. Los Angeles is full of millionaires and the poor people barely scrape by, and all the houses belong to the billionaires and movie stars, the rest of the houses are made of wood and they are pretty crappy. There are 3,000 Mexicans in Los Angeles, who have to work like mules in order to compete in business with the gringos.3

Already Frida was witnessing the gap between rich and poor, Mexican and gringo, something that raised her hackles every time. Frida felt things on a deep level. She was “direct and honest in her thoughts and in her actions,” her niece Isolda observed.4 But Frida’s younger sister, Cristina, would often say, “Just try to be a little less vehement, would you?”5 Frida knew she couldn’t be so forceful when she was speaking with Diego’s patrons; she would have to temper her quips, witticisms, and cutting remarks.

Back on the Southern Pacific train bound for San Francisco, Frida took out a sheet of white paper. Drawing straight lines that reached to the top in a vertical sweep, she formed rectangular skyscrapers. In front of this cityscape, she drew water and a self-portrait. This drawing, now lost, conveys Frida’s connection to cities and to the ocean, to culture and nature. Both would remain important to her for the rest of her life: she associated her father’s German relatives with being an ocean away, her mother’s Mexican heritage with the beauty of the land, and her father’s intellectual and artistic pursuits with urban cultural centers.

She’d grown up in Coyoacán (in Nahuatl the name means “place of coyotes”), a picturesque village with trees, flowers, a river, and dirt roads. It’s a place that embodies the turbulent and syncretic history of Mexico. The Spaniard Hernán Cortés made Coyoacán the first capital of New Spain. He eventually moved the capital to present-day Mexico City, where he proceeded to demolish the old sacred precinct, dominated by a twin pyramid, and replace it with a symbol of the new, a Catholic church—a move he hoped would destroy Aztec deities, philosophy, and culture. But he failed to realize one important fact: the old could not merely be toppled to make way for the new.

The Aztec notion of duality remained rooted in the land, and it shaped Frida’s psyche. She loved growing up surrounded by nature, but she could also experience urban life and culture, as Mexico City was only an hour’s bus ride away. It was a modern, international metropolis with a rich yet painful and layered history, from the great Aztec empire to the conquering Spanish and French, along with Bavarian, Chinese, and American influences. During Frida’s adolescence, “it was a lovely, rose-colored city of magnificent Colonial churches and palaces, mock-Parisian private mansions, many two-story buildings with big painted gates (zaguanes) and wrought-iron balconies; sweet, disorganized parks, silent lovers, broad avenues and dark streets,” writes Fuentes.6

Frida was quite familiar with the look and feel of a big city, but she’d never seen San Francisco. After she finished her self-portrait with a city scene and water on the train, she showed it to Diego without any explanation. He later recalled that upon their arrival in San Francisco, “I was almost frightened to realize that her imagined city was the very one we were now seeing for the first time.”7

* * *

On November 9, 1930, the train stopped at Third and Townsend as a crisp breeze whipped across San Francisco Bay. Frida stepped off the train wearing black ankle strap shoes. They were barely visible under her long skirt, which made it appear as if she were “floating,” as friends often observed.8 At five feet three inches and ninety-eight pounds, Frida appeared even tinier next to her six-foot, three-hundred-pound husband, who wore a suit, a broad-brimmed Stetson hat, and heavy work boots. They were a distinctive-looking couple, easily spotted by those who had come to meet them.

Although the gregarious, cigar-smoking Diego was in his element in a group, the observant Frida scanned the crowd like a cat wary of possible predators. Frida was unsure what type of reception she and her husband would receive. When Diego’s mural commission had been announced two months earlier, many in San Francisco had wanted to know why struggling local artists hadn’t been hired instead. The shaky economic times and the uncertain future that lay ahead fueled a collective feeling of resentment. And for a while it looked as though the local artists had won the day. The State Department initially denied Diego’s visa based upon his former ties to the Communist Party. But San Francisco sculptor Ralph Stackpole, who had been friends with Diego for several years, made sure his friend prevailed.

The mural commission had been Ralph’s idea. He felt that someone like Diego, with his fame and genius, would bring prestige to the local art scene and spawn a mural movement—an art for the people. He even managed to get Diego an additional commission for a mural at the California School of Fine Arts (today the San Francisco Art Institute). Ralph, known to his friends as “Stack,” also used his business savvy to help cement Diego’s reputation with powerful art collectors.9 One of those, Albert Bender, the most influential art patron and donor in the Bay Area, shared his enthusiasm for Diego’s mural and easel paintings. So when Diego’s visa application was denied, Stack turned to Albert and used his connections to get the State Department’s decision reversed. This was a huge victory for Diego and Frida, but it only further fueled the anger and resentment of the protesters. Art Digest lamented, “All is not quiet on the San Francisco front. A storm unprecedented in recent years is shaking the art colony to its very foundations.”10 Two days before Diego and Frida were scheduled to arrive in “The City by the Bay,” stock prices fell to a new low on the San Francisco Stock Exchange. Diego was undisturbed by the controversy, however, as he was used to such battles back home; one might even say he courted them.

* * *

As Frida and Diego walked along the train platform, some reporters approached them for interviews. Diego, a great storyteller who made sweeping movements with his hands when he spoke, was prepared to charm them. But some, like the American critic Rudolf Hess, were suspicious of Diego’s sincerity: “I should say that his predominant characteristic is a conscious showmanship. He is the P. T. Barnum of Mexico.”11 There was a tinge of prejudice as well in a San Francisco Chronicle article that described Diego in stereotypical terms. He was referred to as a “paisano [peasant] with a broad-brimmed hat of distinct rural type” who “piled domestically suitcase after suitcase into [the] car. One looked for groceries or a canary cage to complete the ‘bundle’ picture.” After setting Diego up as a “rural type” who had a “reputation for sarcasm,” the reporter seemed relieved to conclude that this foreign artist was an “hombre muy agradable [a very nice man].”12

Fortunately for this very nice man, there were no signs of any disgruntled artists. Instead, Stack and architect Timothy Pflueger stepped forward to greet Diego and Frida. At one point a photographer snapped a picture of Pflueger smiling and shaking Diego’s hand, while Stack extends his hand. The men frame Frida; they look toward one another while she looks straight at the camera. She wears a distinctive short jacket with two large hombrera-like shoulder flaps—à la matador—over a long dark skirt. In her hand she holds a beret.

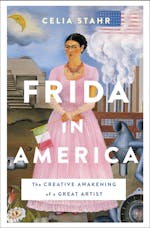

Copyright © 2020 by Celia Stahr