1

Countering Counterculture

Well, whatever, nevermind.

—Kurt Cobain

When I was young, I assumed the way the American landscape was changing around me was somehow temporary. The buildings, after all, looked temporary; ramshackle strip malls, Pizza Huts, and 7-Elevens thrown up chockablock—all of it devoted to a transient purpose, meeting a momentary need in the marketplace.

As my parents’ generation replaced forest and farmland with pavement and a multitude of stores selling ever more elaborate and specific items, I wondered, naively, what would come next: What would replace these things that were built to disappear? Would my generation drastically alter the landscape of America as the previous one had? The answer, of course, was no. What would replace these stores was more stores, piled on top of one another in a mad jumble. Odder still, many people seemed unhappy with this development. The vast parking lots, for example, were friendly to shopping but inimical to human beings. And this is to say nothing of what economists label the “externalities,” all the hidden costs that go into production, like the pollution in the air and the destruction of the environment—once a mere tragedy, now an existential threat in the form of global warming.

The American countercultural revolution, the spirit of ’68 that started with the baby boomers then swept the globe, intended to remake the world into a more equitable and human-centered place. But whatever it did manage to do, it wasn’t quite that.

What happened?

In her 1983 book The Hearts of Men, Barbara Ehrenreich described how, prior to the 60s countercultural revolution, men were constrained into the ideological role of breadwinner. If a man didn’t marry in his early twenties and begin earning a wage to support his family, he was considered abnormal and, in some ways, not really a man. To 1950s American society, a bachelor in his late twenties was either immature or a latent homosexual. And oddly, the first escape out of these oppressive expectations didn’t come from the counterculture, but from Hugh Hefner and Playboy magazine.1

When Hefner abandoned his own domestic, wage-earning existence and created the image of the single playboy, he fashioned an alternative masculine role. Instead of becoming a breadwinner, a man could use his salary to maintain a negative space defined by the absence of a wife and children called a bachelor pad. Properly adorned with the latest stereos, liquors, and the rest of the items advertised in the magazine, the pad was supposed to attract an endless procession of pretty young girls.

However, this Hefnerian vision of manhood was still tied to economic achievement. Like the breadwinner version of manhood, it encouraged conformity and merely changed the system of rewards.

When the first modern American counterculture emerged in the form of the Beats, it challenged both the breadwinner and playboy archetypes by attempting to disassociate masculinity from wage earning. The Beats styled themselves wandering “dharma bums” who slept with women and men as they pleased, and they were as contemptuous of settling down as they were of acquiring material possessions. For this reason, their cultural movement was condemned by both mainstream breadwinning society and Playboy. The Beats were dismissed as insubstantial “Beatniks,” vibing out on nothing, just as the Beats accused the conformist “squares” of doing.

Hippies, following on the heels of the Beats, were also opposed to consumerist society and were equally interested in transcendence. Like the European Romantic artists of the nineteenth century, they were fascinated by the boundless capacity for human experience, achievement, and connection. In this spirit, they created novels, paintings, and music that celebrated the infinite worlds contained within the self.

However, as the new wave of hippie counterculture spread across the country, society responded in a novel way. Mainstream capitalist culture, including Playboy, did not try and push it back. Rather, it got on top and began to surf.

Why was the reaction to hippie counterculture so different?

Un-coincidentally, one of the books that sparked the countercultural revolution, Herbert Marcuse’s 1964 One-Dimensional Man, happened to be on the subject of societal expectations and calibrating one’s own sense of inner gratification. In his best-selling treatise, Marcuse observed that America had begun weaving sex into every aspect of society in the 50s and 60s, transforming it into a dangling reward for conformity.2 Sex became commodified as both an aspect of work and compensation. Many of the cultural victories of the late 60s came so easily because capitalism was hardly opposed to blending work and pleasure. Marcuse noted how employers were encouraging the mingling of public and private life in order to exert a singular form of control. Shops, apartments, and offices were all exposing themselves with huge, transparent windows, and clothes were shrinking to trace the body. All of this dovetailed with the use of sex in the workplace as Playboy had modeled it: as a way to sell status, pleasure, and permission. The oppressive hierarchy of the workaday world, the daily grind of bosses and obligation, was combined, weirdly, with its opposite, the frequent promises of the modern world for adventure and stimulation. Indulgence and toil, personal and private, self-actualization and company loyalty were all to become one.

Now, this is simply an acknowledged part of our reality. Contemporary socialist philosopher Slavoj Zizek often uses the example of the word “Enjoy!” stamped on cans of Coke.3 At first glance, “Enjoy!” reads as an invitation to indulge. But beneath this surface meaning there is a secret assumption. The advertisement has surreptitiously rested its hand on the spigot of our enjoyment, telling us when and when not to enjoy, assuming the burden of answering a difficult philosophical question: What do I enjoy and how long do I go about enjoying? (Coke’s answer: If you have bought a Coke, then go ahead and enjoy! If not, then don’t enjoy.) And we are all used to experiencing the sort of mindless joy (which secretly conceals an abysmal emptiness) that accompanies buying anything; when pleasure, permission, and happiness are, for a fleeting moment, determined not by our own mind, but mediated by the purchase.4

Likewise, we know the same trick can be performed with sexual gratification. It can be reduced to a commodity, in which gazing at an objectified starlet in a film is part of “enjoying” the film. Unconsciously, we have bought permission to leer. Just as acquiring all the commodities in a bachelor pad earns the playboy the right to impress women and therefore the reward of sex.

But Marcuse’s insight was that this system of commodification and permission is not limited to sex or even enjoyment, but expands to what he called “the conquest of transcendence,” in which all that is sublime—one’s personal dreams and the boundless horizon of self-actualization and experience—is circumscribed and applied as rewards for conforming to society.

Why did all of these advertising and entertainment shifts occur in the mid-twentieth century and increase so wildly that today they dominate almost every aspect of our lives? Why have cable channels, movies, and marketing, of all things, multiplied?

This too was articulated by many postwar writers who inspired the counterculture revolution. Many argued the same point: the industrialized economies of wealthy nations like the United States, having fulfilled the basic needs of their citizens, have now turned from manufacturing things they didn’t need to, in effect, manufacturing need.5

These critiques came from leftist cultural critics like Charles Reich and Marcuse, but also conservatives such as Catholic political commentator Reinhold Niebuhr and liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith. All warned that if America did not stop producing tremendous waste and absurd new visions of what was considered affluent to sell, the country would eventually become a nightmarish version of itself, in which the fabric of its values and communities (not to mention its public services) would tear under the weight of industrial marketing.

As Marcuse put it, after “true needs” such as “nourishment, clothing, [and] lodging at the attainable level of culture” were met, the industrial engines that generated these goods didn’t simply shutter their factories and declare their jobs done. Instead, they discovered it was far more profitable to simply generate false needs by convincing people “to relax, to have fun, to behave and consume in accordance with the advertisements, to love and hate what others love and hate.” These items could be sold again and again because they created a “euphoria in unhappiness.”6

To this end, manufacturers hit upon a method that Reich called “substitution,” in which false needs were generated by a denial of true needs. If, for example, your modern life lacks adventure, you can experience adventure on TV. If you’re unable to wander through the beauty of un-despoiled nature, you can do so in a video game. And if you are isolated, you can participate in the ersatz interaction of virtual communities, such as message boards and social media.

By denying true need, the false need is generated. And it carries all the satisfaction of scratching a mosquito bite. As false, it is encoded with a sort of planned obsolescence, so that, ultimately unsatisfied, you seek out the same inadequate remedy again to achieve momentary relief. In other words, the more unsatisfying the substitution (for example, processed food for fresh), the more profitable the enterprise. So when the intricately duplicative art of mass media nests in the soul like a cuckoo, replacing real experience with simulation, it is not so much a flaw as a feature. The manufactured impostor not only thrives on what once fed the real need, but attempts to murder its rivals by extinguishing desires for genuine experience.

This meant that after the countercultural revolution of the late 60s, the hippies’ message of boundless enjoyment free from the authority of a Big Other, who told you when and how to live your life, was ironically usurped by corporate marketers looking for ways to pretend that their products gave the consumer access to a world of limitless pleasure unregulated by any authority. They neatly fenced off what were in fact free possibilities for happiness, and separated pleasure into discrete chunks limited by how much the consumer could spend.

Hippies were opposed to the isolating competition of capitalism and the shallow material world of commodification and consumption. But this is exactly where we find their image today, plastered on packaging in the health food aisle, invoking the idealism of a better world to sell unadulterated chicken, refined ice cream, home-brewed drinks, and balms and oils you can buy by the ounce to make you feel better.7 When we enter high-end, hippie-themed stores like Whole Foods, we hear a pastiche of counterculture anthems—The Doors, The Ramones, The Clash, disembodied voices from different eras all growling angrily about the way society is structured—piped in to convince us to let loose and enjoy ten-dollar teas. Even the hippies’ boundless transcendence is chopped up and sold by the hour as meditative yoga sessions.

The hippies’ demands for a new power structure and a new way of existing in society were not met, but the smaller items on their list, those that had to do with individual lifestyle pleasures, were granted almost immediately. The Beats and their predecessors, men writhing away locked in breadwinning gray flannel suits, got what they asked for: new outfits. Casual bell bottoms and jeans became appropriate, as did long hair. The reinvention of music through the medium of technology, electric rock ’n’ roll, became a new commodity market. And to appeal to the hippies’ interest in exploring nature and the body, industry and marketing produced expanding waves of workout gear, cosmetics, and outdoor equipment. Obscure sports came into vogue, and with them new industries: surfing, rock climbing, parasailing.8 The hippies became a “me generation” who explored their new horizons, literally, with new commodities.

This co-optation didn’t end with the hippies, but rather inaugurated a mad half century in which an ever-expanding mainstream consumer culture chased down and trapped the countercultures that harassed it. Each time a counterculture was snagged, it was then transformed, like a vampire, into a soulless husk that served the enemy.

The contest resembled something out of a Cold War computer simulation. The two forces, consumer culture and counterculture, were locked in a struggle for survival, constantly adapting in an attempt to digest the other. Strains of counterculture perished, and new mutations were born with adaptive counterstrategies to avoid being immediately devoured.

When punk emerged in the 1970s, it was a porcupine, literally armored and covered in spikes. Unlike the welcoming hippies, it appeared to be designed to resist being swallowed up. It embraced everything mainstream culture wasn’t: anything ragged, filthy, offensive, brutal, disgusting, or weird. For this purpose—just as 4chan would later—it adopted Nazi imagery in an attempt to shrug off co-optation.

And though punk today is mostly remembered as a fashion statement and some albums you can buy, beneath the outfits were the far-left ideas and political aspirations of the 68 Paris uprising of antiauthoritarian Marxists who aspired to resist American imperialism, capitalism, and consumerism.

But in the succeeding years, capitalist marketing seized upon punk with eager relish, bisecting and chopping it up into bite-size segments. Just a few years after punk died, Madonna was prancing onstage in the same studs and spikes, singing about how “we are living in a material world and I am a material girl,” flirting with the same duality of pleasure and permission that existed at the center of marketing.

In response, counterculture dropped its world-changing aspirations. Hippies had wanted to reinvent society. The punk aesthetic reveled in its crumbling urban decline. Artists did not reach outside art, but inward toward fantasy and self-reflection, only able to produce Romantic art: proof that there was more to the world than what it was, that it could be imaginatively reinvented. Though the work quickly became infected with the despair of being used by the forces it despised.

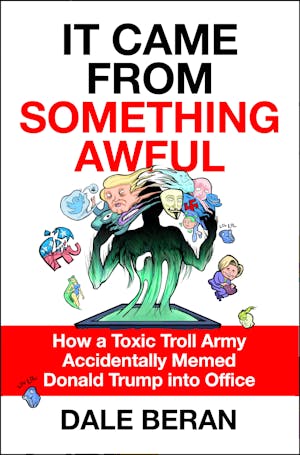

Copyright © 2019 by Dale Beran