ACT 1

Backstory

I’M GOING TO LET you in on a little secret—the real reason so many people from far away risk everything to come to the United States. It’s the backstory you’ve never heard. But it’s so obvious, it’ll make you stop and wonder: how does the truth always get so buried? It’s the reason my parents came here.

Mom and Dad met over a game of poker in Casablanca. In the crowded salon, people kept coming up to him.

“Namu-bhai, when will you bring Teesri Manzil already?” someone asked about the latest hit from back home. “I’ve been waiting forever, yaar.”

Dad was the filmwalla—a film distributor. Not for Hollywood. For Bollywood, which is the world’s largest film industry. The B stands for Bombay, where it’s based. It was Dad’s job to take reels of film and get them to theaters across Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. This was the 1960s, when movies were still literally printed on a thin black strip of glossy paper called film.

It was taxing work. He rode around on his bicycle, just like the boy in Cinema Paradiso, only with an Arab-world twist. Dad was also the censor. He’d take scissors and cut out each and every scene where a man and woman got too close. And mind you, too close did not mean kissing on the lips. Indians wouldn’t go as far as those Americans did. But there was the occasional suggestive shot—cheeks brushing or a long embrace. For the Arabs of North Africa, that was going too far.

“Don’t cut too much, Namu-bhai,” the Hindus at the poker table chided him. “Leave something juicy for those of us who are not Muslim.”

Mom and Dad didn’t convert to Islam. That fact defined their lives early on. Dad was born in Karachi, which used to be part of India, back when it was still under British rule. While the Brits spent more than three centuries colonizing the subcontinent, they were in a big hurry to leave. They decided four months before departure to divide the land into two parts: Pakistan for Muslims, India for Hindus and Sikhs. The Partition—as it’s called—was set for August 15, 1947.

The Brits didn’t consult a single astrologer, which was ludicrous. While religions were at war, everyone agreed: consult the star experts before any major decision—be it a wedding, the naming of a child, the divorce of a country. Astrologers jumped up and down, warning the date was ominous. It would result in untold misery.

They were right—though to what extent is unknown, a data point lost in history. The widely cited estimate of 15 million displaced and 1 million killed is a gross understatement, leading scholars say; and there was no serious effort to do a body count.

Dad was six years old at Partition. A gang of men with burning torches and sticks came banging on his family’s front door. His mom grabbed the kids and pushed them out the back. “Hide on the terrace,” she ordered them. The next day, they were all on a boat sailing from Muslim-held Karachi down to Hindu-held Bombay, with just the clothes on their backs.

Mom was from the same region as Dad—it’s called Sindh—but from a different city. She was born in Hyderabad, about a year before Partition. Her real birthday is a mystery. It may have been in August or September. No one can tell for sure. In the middle of a freedom struggle or civil war, it’s hard to remember what day a mother goes into labor.

The man in charge of drawing the line through the homelands of 88 million human beings was a lawyer who’d never set foot on the subcontinent. He did, however, go to the same prep school as Britain’s prime minister. The Brits believed that with his “objectivity”—modernity’s religion, the Western cult of judgment without empathy—the First World would bless our Third World. He used a low-resolution map as his guide.

His final Partition map was not revealed to the leaders of newly independent India and Pakistan until the celebration parties were over. It was a tough morning-after pill to swallow. No side was happy. As politicians squabbled, so too did the masses. Cities that were once cosmopolitan melting pots erupted in tribalism. Muslim babies were put on skewers and roasted. A trainful of Hindus and Sikhs were butchered, arriving into a station as corpses. There were so many dead bodies, dogs turned their noses up at second-grade meat.

Everyone at the poker party in Casablanca had Partition in common—the blood that soaked the streets, their clothes, and, for some, even their own hands. Call them Pakistani or Indian, refugee or expat, they were defined by that day and eager to forget. It was time to live in happier times.

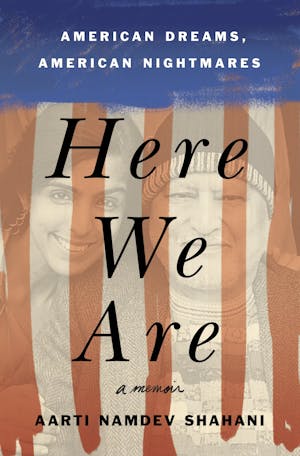

Copyright © 2019 by Aarti Namdev Shahani