1

ALADDIN’S CAVE

London wears many different faces, depending on whom it’s talking to. There is the pageantry and ceremony of the Changing of the Guards: all red-jacketed soldiers, glossy horses and cheering crowds. That’s for the tourists. There is the steel and glass of the City, London’s financial district, garrisoned by an army of bankers and clerks who teem across the bridges in the early morning. That’s for the business folk. There are the suburbs, with their semi-detached houses, hedges, no-through-roads and parks. That’s for the locals.

And then there are places like Finchley, in northwest London, and the short street called Woodberry Grove, where the cars were new a decade ago, and the nearest stores sell Polish beer and tabloid newspapers. It isn’t a street you’d visit, or even notice, unless you had a good reason to, which is perhaps why Paul Manafort situated one of his companies—Pompolo Ltd—at house number 2.

According to the indictment prepared by the Office of Special Counsel Robert Mueller, Manafort, Donald Trump’s former campaign chairman, moved some $75 million through various offshore bank accounts, much of which he used to buy high-end properties and luxury goods. He earned this money working in Ukraine, primarily for thuggish ex-president Viktor Yanukovich, and was found guilty of hiding it from the Internal Revenue Service, as well as assorted other crimes. The meticulous indictment listed the companies through which he owned the bank accounts that channeled this money, which is how we know about Pompolo Ltd. Pompolo controlled a bank account that paid $175,575 to a Florida home entertainment company and $13,325 to a landscape gardener in the Hamptons on the same day—July 15, 2013.

That may well be all that Pompolo ever did. It had been created just three months earlier and was dissolved by the UK’s Companies House a year later, something that happens automatically if companies do not file the necessary paperwork. I had come to 2 Woodberry Grove to look at the street address that was Pompolo Ltd’s supposed base of operations.

It was an uninspiring destination, a two-story office building of russet bricks, some of them overlaid with beige stucco. Its roof tiles appeared to be held together by clumps of moss, and the window frames were stained so dark they were barely recognizable as wood. A row of doorbells ran down the side of the door. I pressed one of them and was greeted by a middle-aged man with a South African accent and a faded T-shirt advertising the English heavy metal band Iron Maiden. He ushered me inside.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from a place that had been a junction in the financial plumbing that Manafort used to suck money out of Ukraine and pour it into luxury goods in New York and Virginia, but I’d imagined something more exciting than a tidy, dull office with an institutional gray carpet and a poster advising workers on how to sit at their computers to avoid damage to their backs. While I waited for the Iron Maiden fan’s boss, I listened to two women gossiping about their weekend plans, and tried to peek into their cubicles. Sadly, the boss wasn’t available, and I left with nothing more than an email address (his reply, when it came, included a denial of any wrongdoing and a strong tone of exasperation: “I cannot speak with any authority as to what motivations ‘people like Manafort’ may have, so I am afraid that you will have to draw your own conclusions”) as a reward for the fifteen-minute walk to Woodberry Grove from the Tube station.

There are two places to go next with this story. The first would be to give up on Pompolo as a dead end and instead focus on Manafort, on his sordid client base, his amoral maneuvering and his remarkable appetite for luxury goods. The second would be to look back at 2 Woodberry Grove and to ask why Pompolo—a company with access to significant amounts of cash—would base itself in an unglamorous part of an unfashionable corner of London.

It’s understandable that most journalists would prefer the first approach. It makes a more compelling story to write about ostrich-skin jackets and luxury condominiums, about the way Manafort laundered the reputations of dozens of unlovely politicians and oligarchs, than it does to describe ugly British institutional architecture. But the second approach is the more rewarding, because if we can understand what links Manafort to Woodberry Grove, we gain a glimpse behind the personalities, into the hidden workings of the financial system, into the secret country that I call Moneyland.

The indictment against Manafort, and against associate Rick Gates (in whose name Pompolo was registered), revealed the existence not just of Pompolo Ltd, but also of companies in the Caribbean states of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, as well as in Virginia, Florida, Delaware and New York. And these companies had multiple bank accounts, supposedly independent of each other, but in reality connected by their shared—and hidden—owners. They moved money back and forth between each other in a ceaseless and bewildering dance, the patterns of which are far too complicated for even many experts to understand. Trying to draw the complexity of the financial arrangements among all of these entities is a job for a whole team of law enforcement professionals; it’s all but impossible for a layman.

Manafort and Gates exploited this system for a decade or more, but they didn’t create it. Nor did they seek out 2 Woodberry Grove and decide to make it their base of operations. That was done for them by an entire industry of people who enable the crimes of people like them, people with money to hide. The real tenant of the office building in Finchley is A1 Company Services, which creates companies for its customers and gives them a postal address. A1 Company Services is emblematic of something far greater than a political scandal, even one as big as this. It represents a system that is beggaring the world by hiding the secrets of the rich and powerful.

Manafort’s secrets were so well defended that had Robert Mueller not started investigating the former Trump campaign chairman, he would almost certainly have gotten away with his crimes. And this is a worrying thought, because there are many other people still using the exact same system. House number 2 on Woodberry Grove is or has been home to thousands of other companies—16,551, according to one database—as have the addresses Manafort used in the Grenadines, and in Cyprus, not to mention those in the United States.

Most people view Paul Manafort as important only insomuch as he revealed corruption surrounding the election of Donald Trump. But in fact, his link to Trump inadvertently gives us a window into something much bigger, a shadowy system of which few of us are aware. It’s a system that is quietly but effectively impoverishing millions, undermining democracy, helping dictators as they loot their countries. And we can learn more about this world by looking at one of the biggest clients for Manafort’s services: Viktor Yanukovich, ex-president of Ukraine.

* * *

Yanukovich ruled Ukraine for four years, from 2010 till 2014, during which time he enriched himself and bankrupted his country. Finally, Ukrainians got fed up, and thousands protested throughout the cold winter of 2013–14, until he fled. The riches he left behind revealed him to have had tastes so baroque as to make even Manafort look restrained. The spreading grounds of his palace at Mezhyhyria included water gardens, a golf course, a nouveau-Greek temple, a marble horse painted with a Tuscan landscape, an ostrich collection, and an enclosure for shooting wild boars, as well as the five-story log cabin where he indulged his tastes for the overblown and the vulgar. It was a temple of tastelessness, a cathedral of kitsch, the epitome of excess.

Everyone had known that Yanukovich was a criminal, but they had never seen the extent of his haul. At a time when ordinary Ukrainians’ wealth had been stagnant for years, he had accumulated a fortune worth hundreds of millions of dollars, as had his closest friends. He had more money than he could ever have needed, as well as more treasures than rooms to store them.

All heads of state have palaces, but normally those palaces belong to the government, not to the individual. In the rare cases—Donald Trump, say—where the palaces are private property, they tend to have been acquired before the politician entered office. Yanukovich, however, had built his while living off a state salary, and that is why the protesters flocked to see his vast log cabin. They marveled at the edifice of the main building, the fountains, the waterfalls, the statues, the exotic pheasants. Enterprising locals rented bikes to visitors. The site was so large that there was no other way to see the whole place without exhaustion, and it took the revolutionaries days to explore all of its corners. The garages were an Aladdin’s cave of golden goods, some of them perhaps priceless. The revolutionaries called the curators of Kiev’s National Art Museum to take everything away before it got damaged, to preserve it for the nation, to put it on display.

There were piles of gold-painted candlesticks, walls full of portraits of the president. There were statues of Greek gods, and ivory carved into intricate oriental pagodas. There were dozens of icons, antique rifles and swords, and axes. There was a certificate declaring Yanukovich “Hunter of the Year,” and documents announcing that a star had been named in his honor, and another for his wife. Some of the objects were displayed alongside the business cards of the officials who had presented them to the president. They had been tribute to a ruler: down payments to ensure that the givers remained in Yanukovich’s favor and thus could continue to run the scams that had made them rich.

There was an ancient tome, displayed in a vitrine, with a sign declaring it to have been a present from the tax ministry. It was a copy of the Apostol, the first book ever printed in Ukraine, of which perhaps only a hundred copies still exist. Why had the tax ministry decided that this was an appropriate gift for the president? How could the ministry afford it? Why was the tax ministry giving presents like this to the president anyway? Who paid for it? No one knew. In among a pile of trashy ceramics was an exquisite Picasso vase, provenance unknown. A cabinet housed a steel hammer and sickle, which had once been a present to Joseph Stalin from the Ukrainian Communist Party. How did it get into Yanukovich’s garage? Perhaps the president had had nowhere else to put it.

Soon the queue at the gate stretched all the way down the road. The people waiting looked jolly, edging slowly forward to vanish behind the museum’s pebble-dashed pediment. When they emerged again, they looked ashen. By the final door was a book for comments. Someone had summed it up nicely:

“How much can one man need? Horror. I feel nauseous.”

And this was only the start. Those post-revolutionary days were lawless in the best way, in that no one in uniform stopped you from indulging your curiosity, and I exploited the situation by invading as many of the old elite’s hidden haunts as I could. One trip took me into the heart of a forest outside Kiev. Anton, a revolutionary I’d befriended, stopped the car at a gate, stepped off the road into the undergrowth, rustled around and held up what he’d found. “The key to paradise,” he said, with a lopsided smile. He unlocked the gate, got back behind the wheel and drove through.

To the right was the glittering surface of the Kiev Reservoir, where the dammed waters of the Dnieper River swell into an inland sea dotted with reed beds. Then came a narrow causeway over a pond by a small boathouse with a dock. Ducks fussed around wooden houses on little floating islands. Finally, Anton pulled up at a turning circle in front of a two-story log mansion. This discreet residence, which went by the name of Sukholuchya, was where Yanukovich came with old friends and new girlfriends when he wanted to relax.

Anton first came here with his daughter in the few hours after the president fled his capital in February 2014. He drove down that immaculate road to the first gate, where he told the policemen he was from the revolution. They gave him the key, let him pass. Now Anton opened the door and led the way in. He had changed nothing: the long dining table with its eighteen overstuffed chairs were as he had found them, as was the heated marble massage table. The walls were dotted with low-grade sub-impressionist nudes—the kind of thing Pierre-Auguste Renoir might have painted if he’d moved toward soft porn. The floor was of polished boards, tropical hardwood; the walls were squared softwood logs, deliberately left unfinished, yellow as sesame seeds. There were no books.

Strange though it sounds, it was the bathrooms that really got to me. The house held nine televisions, and two of them were positioned opposite the toilets, at sitting-down height. It was a personal touch of the most intimate kind: President Yanukovich had been someone who liked to watch television, and someone who needed to spend extended periods on the toilet. The positioning of the televisions had clearly been intended to prevent the necessity from getting in the way of the hobby. While Ukraine’s citizens died early, and worked hard for subsistence wages, while its roads rotted and its officials stole, the president had been preoccupied with ensuring that his constipation didn’t impede his enjoyment of his favorite television programs. Those two televisions became a little symbol for me of everything that had gone wrong, not just in Ukraine, but in all the ex-Soviet countries I’d worked in.

The Soviet Union fell when I was thirteen years old, and I was highly jealous of anyone old enough to be experiencing the moment for themselves. In the summer of 1991, when hard-liners in Moscow tried and failed to re-impose the old Soviet ways on their country, I was on a family holiday in a remote part of the Scottish Highlands, and spent days trying to coax the radio into cutting through the mountains and telling me what was going on. By the time our holiday was over, the coup had failed, and a new world was dawning. The usually sober historian Francis Fukuyama declared it to be The End of History. The whole world was going to be free. The Good Guys Had Won.

I longed to see what was happening in Eastern Europe, and I read hundreds of books by those who had been there before me. When at university, I spent every long summer wandering through the previously forbidden countries of the old Warsaw Pact, reveling in Europe’s reunification. At graduation, most of my fellow students had lined up jobs, but not me. Instead, I moved to St. Petersburg, Russia’s second city, in September 1999, overcome with excitement, drunk on the possibilities of democratic transformation, of the flowering of a new society.

I was so full of the moment that I didn’t realize I had already missed it, if indeed it ever existed in the first place. Three weeks before my plane touched down at Pulkovo Airport, an obscure ex-spy called Vladimir Putin had become prime minister. Instead of writing about freedom and friendship over the next decade or so I found myself reporting on wars and abuses, experiencing paranoia and harassment. History had not ended; if anything, it had accelerated.

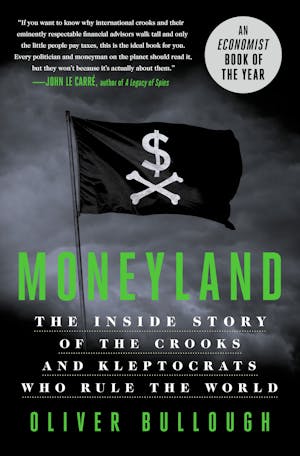

Copyright © 2019 by Oliver Bullough