We met the others at nightfall on the western side of Empalme, past the square and beyond the well. It was where Julio and his men had made their camp over a month ago. We ignored them as we passed, but I could see them watching us as we went by, the fire lighting up their dour, bitter faces. But they said nothing, did nothing, and we joined the rest of the celebration.

Rogelio was there and already drunk, strumming his guitar dramatically while two women harmonized over it all, their voices a complicated dance of melody and sadness. They sang of leaving their husbands behind and making the journey across the endless desert together. “Montamos juntos y nos hacemos uno,” Amada sang, almost laughing as she made eye contact with her novia, Carmita.

They were not the only sound in the clearing, as most of los aldeanos were spread around an enormous central fire. This was a celebration of our lives, of surviving another day in the scorched and unbearable world that You left for us. A respite from Your harsh stare. Even without You in the sky, though, las estrellas were many, were brilliant, and they cast a glow over all.

I weaved through the crowd, holding the basket out, offering our tortillas for others. I had helped Mamá make them earlier that evening as You set in the west. We had formed a line behind our home, my parents and I, with my brother, Raúl, at the end, working as the earthy scent of the first burning coals floated up to my nose. Mamá made her tortillas thick and crispy around the edges, la masa blooming into a savory taste on the tongue. She kissed Papá, ran her fingers through his long hair, then yelled at Raúl, who had let one of the tortillas linger on the heat for too long.

It was an important part of our daily ritual. We all took something to our village gatherings. None of it was sold; this was our offering to one another. La señora Sánchez came with her guisado de cabra, and I could smell the spices from across the clearing as she filled bowls with the hot, savory stew. People greeted one another, perhaps not so loudly as usual—our voices thick with increasing worry since Julio’s arrival in Empalme.

But we were still here, still alive, and this tradition had lasted for many, many years, since long before I was born. At night, there was a great sense of freedom, but as was usually the case for me, it came at a cost. I had already made my way to the other side of the fire, greeting Lani and Omar, when Rogelio stumbled over, nearly crashing into me. “Cuentista, cuentista,” he slurred.

I saw Lani roll her eyes at me. Rogelio was always like this.

“Cuentista, I need you.”

“I know,” I said, exhausted. “But not now. It is barely nightfall.”

“I will find you later,” he said, smiling, a dribble of spit slipping out of the corner of his mouth.

“I’m sure you will,” I muttered.

Lani reached a hand out. “We do appreciate you, Xochitl,” she said, her light eyes reflecting the fire behind me. “Don’t worry about him. As long as he’s talking to you, we’ll all be fine.”

I nodded at her, but bit back what I wanted to say. Everyone would be fine; she was right about that. I watched Lani laugh at something Omar had said, and the thought raced through me: But am I going to be fine?

Something bumped into my leg, and I looked down to see the wooden cart belonging to la señora Sánchez, a large metal pot of guisado de cabra in the back. “Disculpe, Xochitl,” she said, and she waved at me with her wooden arm, the one she got in Obregán after she’d lost the one she’d been born with. “Would you help me for a bit?”

I smiled at her. I liked la señora Sánchez, and enjoyed her stories of her early days in Empalme, but what I liked most about her was that she never lied to me. “Sure,” I told her, and I took hold of the cart and pulled it after her. She greeted the other aldeanos, offered them el guisado, and then moved on.

I kept up as best as I could, saying hello to those gathered around the fire, but otherwise remaining silent. When Ofelia came to get a bowl, she nearly tripped over me. “Didn’t see you there,” she said, then turned back to la señora Sánchez without another word to me. There weren’t many of us in Empalme—we were so far from Obregán to the north and Hermosillo to the south—but most people treated me as Ofelia did. They rarely saw me unless they needed me, and I knew that as soon as Ofelia had to tell me a story, she’d be much kinder.

Now, though, she was locked in conversation with la señora Sánchez, and I didn’t matter. “He’s going to start interfering with los mensajeros,” Ofelia insisted. “And I can’t have that. I’m waiting for some very important mensajes from my family. I cannot have them delayed.”

“Perhaps there are more pressing issues, Ofelia,” la señora Sánchez said, her mouth curling up in irritation. “Though I sympathize.”

“What are we doing about Julio?” she demanded, as if la señora Sánchez had said nothing at all. “Are we just letting him take over our well? What’s next? Our food?”

Papá came up to stand beside me. “He’s only a bully,” he said. “We have enough water that we can get on our own. We’ll just bore him until he leaves. Solís will protect the rest of us.”

Like instinct, we all made the sign: our palms dragged across our eyes, then passing them down to our chest. A reminder to see the truth, to believe the truth. As long as we kept the truth in our hearts, as long as they all spoke it to me, we would be spared from Your wrath.

But I made eye contact with la señora Sánchez, and she was not thrilled with mi papá’s calm. She was scowling.

I looked to Papá, uncertainty snaking up my spine. “But what if it gets worse?” I asked. “What if he does take more from us?”

“We’ll be okay,” he said, running his hand over my head, into my long hair. “Just keep helping us tell Solís the truth.”

La señora Sánchez cleared her throat loudly. “Beto, I’m not so sure about that.”

“There’s no need to doubt Solís, señora,” Papá shot back.

“Well, you don’t have the same history with Julio as I do,” she snarled, and I winced.

“Papá, are you sure we’ll be okay?” My voice trembled as I spoke.

He ignored me. “Señora, can you speak to the guardians again? Find out if they need anything from us? Or if we’re drifting too far from Solís?”

I knew what he meant: Did I need to do a better job? Was there more I could do? But he wouldn’t say that directly, only hint at what was expected of me. That’s what they all did. I was the undercurrent, the quiet assumption in all their lives, the person they depended on to keep them safe. But would I ever get to be anything else?

La señora Sánchez jerked her head to the side. “Why don’t you ask them?”

We looked in the direction she had gestured.

They stood there, their eyes glowing.

Every aldea, every colonia, every ciudad, had its own set of guardians. You left them behind to watch over us, to act as protectors where You could not. Ours were lobos, giant and towering, who hid in caverns and underground dens during the day, their coats thin and brown, blending in with the colors of the desert. They spoke only to the one they had chosen, and that was la señora Sánchez. I grew up wishing that, as la cuentista of Empalme, I was the one they spoke to.

But as they did tonight, they always stared at me, unmoving, silent.

Papá made the sign, then spoke. “You know they won’t talk to me, señora.”

She shrugged. “Then don’t tell me what I should do.”

We moved on, and I gave Papá a sympathetic look as he pulled his long hair behind and tied it off. He always did that when he was embarrassed. As la señora Sánchez served others, I stood there and watched the crowd that had gathered. How many of us were there left in Empalme? Forty? Fifty?

I watched Raúl chase after Renato, his best friend. My brother bounded past me, his round cheeks bouncing, and jealousy struck at me. At least he had someone. Whom did I have now? Ana y Quique had left with their parents to travel down to Hermosillo, a journey that would take them a full week. Doro had gone to Obregán last month with her tío, finally ready to continue in the family business.

No one ever came back. They ventured out of Empalme, they found new lives, and then they never returned.

This was my life. I was la cuentista of this place, and I was to remain here, purifying los aldeanos de Empalme, until I passed the power on to someone else in death.

I excused myself and walked around to the eastern edge of the fire. I passed Ofelia, who was complaining to someone else about her mensajes.

I blocked her out.

I stared up at the sky, watched each of las estrellas sparkle into existence. Sometimes, after a particularly difficult ritual, I would lie on my back on the earth, and I would let las estrellas surround me. They would fill every bit of my field of vision, and I would imagine that there was nothing else in the world. Just the desert beneath me and las estrellas above. I was hidden from You, and I would allow the loneliness to settle deep in my body. It was a part of me, one I had no means of alleviating, except for las poemas.

But as I thought of those words I had found out in the sand, I sensed someone staring at me.

After turning around, I locked eyes with her. Emilia. She was on the opposite side of the fire, gazing in my direction. I glanced about, and her father, Julio, was nowhere in sight.

There was an empty space around Emilia, as if no one could fathom standing close to her, couldn’t bear to speak with Julio’s daughter. I watched for a while, saw the others move even farther away.

She tilted her head, staring.

I rolled my eyes. I wanted nothing to do with her.

So I turned around once more and leaned my head upward, my back to the fire, and I watched las estrellas. I stuck my fingers into the waistband on my breeches and felt the edges of the small drawstring pouch I always carried with me.

One touch was all I needed.

I watched las estrellas. They watched me back. I stood like this until my neck ached, until I had drowned out the noise of Empalme. Our nighttime celebration faded around me as exhaustion crept into our bodies, pulled us back to sleep, and soon, Papá was asking me to help la señora Sánchez home. I agreed, but it was mostly because I knew she would keep to herself.

So I enjoyed her quiet presence as I pulled the cart back, the crunch of the wooden wheels on sand the only sound between us.

But I needed to know. As we pulled up to her home, crafted of bricks made of mud, I sighed. “Do you think we will be okay?” I asked. “Have the guardians said anything to you about Julio?”

“No sé,” she said. “I have never known the guardians to be so silent. And I’ve lived in Empalme for nearly seventy years.”

“Am I doing enough?”

She smiled, caressed my arm with her fingers until they looped with mine. Then she gave me a gentle squeeze. “Niña, sometimes I think you do too much for us.”

She took her empty pot indoors without another word, and I walked the rest of the way home, my eyes drifting up to las estrellas every so often. I was alone underneath them.

They comforted me. They always did.

Rogelio called my name. It drifted in our home like a wind, like a lost calf bleating for its mother, and I bolted upright from the floor. He called it out again, and I cast a glance down at Raúl, who slept soundlessly on the ground. As he always did. Nothing ever seemed to wake him, and I sent up a silent prayer to You, thankful that he would not have to hear this.

Mamá and Papá were asleep, too, not far from us, and Papá’s soft snoring filled the room. Mamá rustled in her sleeping roll, and I sneaked out while I could. She was the lightest sleeper of them all, but that night, I was thankful she did not wake. I pushed aside the burlap curtain that crossed over our doorway, and he swayed there, his arms drooping at his side, and my name slipped off his tongue again, jumbled together.

“Xochitl.”

I stepped out to Rogelio and reached forward, intending to direct him away from our door, but the smell hit me. I choked. Tesgüino, his favorite.

Despite how drunk he was, he still saw me shrink away from him. “Lo siento, Xochitl,” he said. “Pero te necesito. He hecho algo terrible.”

He slurred all of it, the words coated in alcohol and regret. It was always the same with Rogelio: the sadness. The numbness he sought in drink. The begging. Even if I hadn’t been a cuentista, I would still know his secrets. He wore them on his clothing, on his breath, on his face.

I shook my head. “Now, Rogelio? Do I have to now? It’s the middle of the night.”

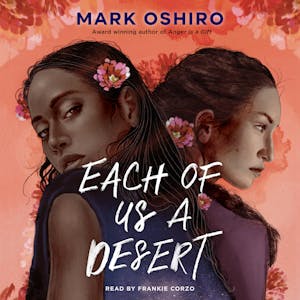

Copyright © 2020 by Mark Oshiro