INTRODUCTION

What is racism? Where did it come from? Why does it still exist? And what can we do about it? These are the kinds of questions that may have led you to this book. These are also the kinds of questions that have inspired me as an educator, researcher, and sociologist. Over the course of my career I have spent years studying racism, and the struggle against racism in this country and in Europe as well.

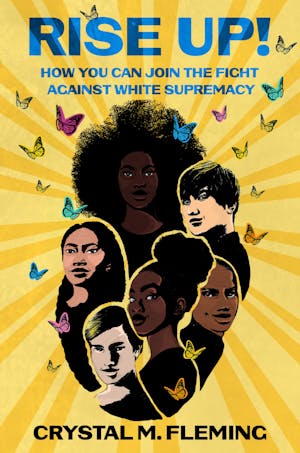

Before we jump in, let me properly introduce myself! I’m Dr. Crystal Marie Fleming, and throughout this book I’ll be your personal guide in unpacking the history and ongoing realities of racism. I was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and I’m now a professor and social scientist living in New York. And, even though I’m African American and have spent many years studying issues of race, I did not know much about racism as a young person. In fact, it wasn’t until I attended college that I really began to understand what racism means and how it operates.

My amazing mother worked hard to make sure I believed I could do anything I set my mind to. For Mom, this meant shielding me from racist beliefs. But it also meant that I grew up almost entirely unaware that racism and other kinds of injustice shaped the world around us—and our experience of it.

I still remember the first time I consciously realized I was “Black.” I was in the second or third grade in elementary school. I had recently been admitted to the “Gifted and Talented” track because of my high achievement scores. One day, the teacher—a young White woman—called on me to read a passage from a book. When I finished reading, the teacher told the class that she liked how David, another kid in the class, and I pronounced the word “aunt.” We both said it like “unt” instead of “ant” like most of the other students. I looked at David and then looked at myself and realized that we both had brown skin. That was the first time I really thought about the fact that we were the only Black students in the class. And luckily, that realization was accompanied by a compliment, as the teacher told everyone that our way of saying “aunt” was correct.

Looking back on that moment, I remember feeling happy about having something in common with David. But I didn’t know enough about racism at the time to question why there were only two of us in the Gifted and Talented track.

I also remember reading about slavery and the American Civil War in middle school and thinking that it was such a sad history—without realizing that I myself was a descendant of slaves. At no time do I remember being taught to draw connections between past and present racism. Nor did I learn about the ways in which our society today is still structured by racial injustice. As far as I knew, racial oppression was mainly a thing of the past.

In fact, the first person to teach me about racism was not a Black person—but rather, a White man. In college, I took a sociology class taught by Dr. Ira Silver—one of my favorite professors. The class addressed many forms of inequality, including racism. For the first time, I began to learn about injustice and realize how my own life—and the lives of my family and community members—had been shaped by racism and other forms of oppression. I came to understand that being African American meant having to deal with and overcome systemic barriers that had long been invisible to me. I also began to realize that economic inequality and poverty were intertwined with racial injustice.

The class was a huge revelation for me and ultimately changed my life. Learning about inequality as well as activism for social justice sparked my thirst for knowledge and made me decide to become a sociologist. And, as I began to study these issues, my mom started to share with me her own reflections on experiencing and overcoming racism.

It is my hope that you, too, will be changed by reading this book. My goal is to share with you some of the knowledge I’ve acquired about the history and sociology of racism, while also equipping you with tools for standing up against racism and making the world a better place.

As we prepare to dig into this vast and important topic, I want you to begin to think about these questions:

How would you describe your racial or ethnic identity?Do you remember the first time you learned about race?Have you ever discussed race or racism with your family members?What, if anything, have you learned about racism at school?If you’re anything like I was as a kid, you may not have given much thought to these questions before. Or, perhaps you’ve directly experienced or observed racism and you’re looking to learn even more. Either way, take this opportunity to consider your answers to these questions—knowing that they may change over time.

UNDERSTANDING THE MEANING AND ORIGIN OF RACISM

Since this book explores the origin and consequences of racism, it’s important that we clearly understand what the word means. Racism has two basic elements that we need to address—racist ideas and racist practices.1 The first part of racism, racist ideas, is the belief that human beings are divided into superior and inferior racial groups. According to racist ideology, these racial groups or races are thought to represent biological and cultural differences that are permanent and can’t be changed. A major theme we’ll explore throughout this book is the fact that racist ideas have distorted our cultural practices, media representations, and even our laws for hundreds of years.

Social scientists have shown that racist thinking doesn’t just involve the use of racial labels—it involves ranking human groups according to race and creating a hierarchy in which some racial groups are said to be superior or inferior. In other words, if you just describe someone as Black, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you are expressing a racist idea. You might just be using a social label that reflects their cultural identity. But if you describe Black people as a group that will always be inferior (or superior) to others because of their biology or culture, then you would be expressing a racist belief.

When I teach classes about race, some of my students admit that they used to think that racial labels like Black, White, Asian, and Latino have always been used by human beings. But these labels are social constructions. This means that they were created by human beings in a specific place and time.

What we know for sure is that racial labels were invented in Europe during a time of philosophical and intellectual change called the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, which took place from the 1600s through the 1700s, was a period of intense debate and intellectual activity in which educated Europeans (usually wealthy men) began to establish their vision of science as well as notions of individual freedom, liberty, and equality—ideas with which we are still familiar today. It was also during this era that European nations sought to expand their reach by attempting to conquer people living in other parts of the globe, including the Americas and Africa.

One of the ironies of the Enlightenment is the fact that even as Europeans were writing about principles of equality, they were also creating ways of dividing and ranking human beings into groups that they described as civilized and other groups they defined as primitive. It was in this context that Europeans began to invent racial categories and labels, as well as ideas about racial superiority and inferiority. And these same racist ideas were used to argue that (superior) Europeans should dominate non-European groups.

As explained above, racist ideas are just one aspect of racism. The second element of racism involves social behaviors and practices that give advantages and disadvantages to people depending on the racial label that is forced on them. This means that racism is not just about the way we see the world, ourselves, and each other—it’s also about the actions we take, and the actions others take, that create an unequal playing field. In other words, racism involves unfair discrimination and produces a racial hierarchy.

These two components—racist beliefs and practices—create systemic racism. This is very important, because some people mistakenly think that racism is only about prejudice or bias against other groups. But racism is more than just having prejudiced ideas—it’s a system of power that creates opportunities and wealth for people who are viewed as racially superior while creating poverty, hardships, and suffering for people who are viewed as racially inferior.

Another term we should consider is structural racism.2 This refers to the notion that racist ideas and practices in different social institutions—like the family, education, or judicial system—combine to create long-lasting and deeply embedded inequalities.

Take, for example, the case of Black people and people of color in the South Bronx—an impoverished area of New York City. Children and youth living in this neighborhood are exposed to environmental toxins from an early age due to the impact of residential segregation and racist housing policies. As a result of pollution from nearby factories, trucks, and highways, people in the South Bronx struggle with asthma at a much higher rate than most other neighborhoods in the United States.3 Studies suggest that the combination of environmental racism and racism in housing also has negative consequences for health and educational inequalities. According to Claudia Persico, a policy researcher, “even short-term exposure to pollution causes test scores to drop.”4

Copyright © 2021 by Crystal Fleming