INTRODUCTION: The Meaning of AOC

Lynda Lopez

Under the elevated subway train on Westchester Avenue in the Bronx, the part that runs between Castle Hill Avenue and Parkchester, is a vibrant, multicultural, bustling stretch of main drag that somehow manages all at once to feel big city and exactly like home. The road goes past the El Texano restaurant, the Beauty Bar, and the Dollar Tree; it runs up to the main entrance of the Parkchester stop of the 6 train, where a handful of riders exit the station’s doors and pour out into the street every few minutes all day long. Though the subway’s relentless rumbling and the earsplitting screeches of its brakes can be heard, and felt, throughout the day, there is none of the frenetic energy here that you’d find in Manhattan. It’s a low-key and almost quiet outer-borough neighborhood, of mostly black and Latino residents. And in the space right next to the Parkchester branch of the New York Public Library (across from the McDonald’s and the Catholic Guardian Services building) is the Bronx district office of the youngest woman ever elected to Congress. It is in the neighborhood where she was born, and now lives. And it sits just blocks from where I grew up, in the Castle Hill section of the Bronx.

From the beginning, there was something that intrigued me about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—her stunning win over a ten-term incumbent New York congressman and the policy positions that were blowing people’s minds with a progressivism we hadn’t seen from a political newcomer in a while, to be sure. But it was looking at her Westchester Avenue district office address, and seeing her apply red lipstick in the small bathroom of her Bronx apartment in the documentary Knock Down the House, that drew me in a different way. There was some innate understanding there; something that made me want to root for her. It felt not just familiar, it felt as if it validated my being. It made me think of all the women I knew who came before, who put on lipstick in those same small bathroom mirrors. The ones who went out into the world without privilege or a leg up, and raised all of us daughters to go out in that world, steeled by their strength and lessons in self-reliance; the ones who taught us to survive so that the next generation could thrive. Ocasio-Cortez made it clear she came to this run for Congress to make her district, our neighborhood, a better, easier, more successful (more fruitful) place to live. And when you come from this place, it’s hard not to root for that.

I loved my mostly Puerto Rican neighborhood growing up, and still do, but even then, it was hard to ignore its challenges—the simple realities of the struggles here that still exist today. The local child poverty rate is a staggering 40 percent. In health outcomes for its residents, the Bronx ranks dead last in the state of New York: 62nd out of 62 counties, when counting health factors such as obesity rates, smoking, mental health, the quality of air and water, access to healthy foods, unemployment, and income inequality. Schools here are at 105 percent capacity.1 The poorest of the country’s 435 congressional districts is in the Bronx. The economic realities of this place mean that, for most residents, the security of enough doesn’t exist; lack defines the lives of too many.

Whenever I find myself back in this neighborhood, my mind is never far from the grit, strength, and hustle it takes to press through the everyday stress and try to live your best possible life here. If you grow up or raise a family in this neighborhood, your permanent dream is of doing better, even as you know not many around you will rise. Being from here—a good friend I grew up with in the Bronx explained to me once—means that “We have to dream big. We have no choice.”

It’s from this place that I got on the 6 train for the first time, on my own, to go into Manhattan for my first job when I was a high school senior. A true musical theater nerd, I answered an ad one day looking for young part-timers to sell programs and souvenirs in the lobbies of Broadway theaters. My dream gig! Even if it involved riding the subway four days a week to make $15 a shift working for two hours a night. And because I looked as I did, and was from the place I was from, on one of my first days of work as I folded T-shirts at a souvenir booth, one of the ushers at the theater asked me, “You’re Puerto Rican? And you’re seventeen? Where’s your three kids?” And then laughed uproariously with his white friends.

I remember that experience so clearly because it was that “first” most kids of color have when we are young—the first time encountering someone who believes that the fact that we are Latina means they can mock us, that they think we are somehow less than them. It was the very first time I had the thought—I didn’t voice it, though I should have—“Who, exactly, do you think I am? Who am I supposed to be, according to you?”

* * *

Ocasio-Cortez was born in the Bronx in 1989. Four years before she was born a study called the Puerto Rican community in New York “a people in poverty and a community in crisis.” It concluded that Puerto Ricans were one of the poorest ethnic groups in the country, “if not the poorest.” The community’s low economic and social status despite being American citizens, the report argued, was due to a variety of factors, including discrimination and, sometimes, a language barrier.2

Ocasio-Cortez was living in this reality in the Bronx when her parents decided to move the family to a suburb 40 minutes north. It was meant to be a step toward a better outcome for her life, but it didn’t suddenly set the family in economic stability. The loss of her father while she was in college meant that, after graduating, she worked to help her mother fight off foreclosure of their home. Her mother still eventually had to sell the house, and Alexandria moved back to the Bronx. It’s from that place that she decided to run for Congress.

And as soon as she was victorious in her primary race against Democratic incumbent Joe Crowley, she immediately (in our modern media age), found herself the target of relentless policy and personal attacks. When it seemed she was being disingenuous about where she actually lived during her early school years, opponents pounced. One tweet in particular showed a photo of the family’s modest house in suburban Yorktown Heights. The author of the tweet called it “a far cry from the Bronx hood upbringing she’s selling.” Though it was clear he mostly just wanted to call her out, I couldn’t brush past “the Bronx hood” remark. “Bronx hood upbringing.” What, exactly, does that mean to you? Who is she supposed to be, according to you?

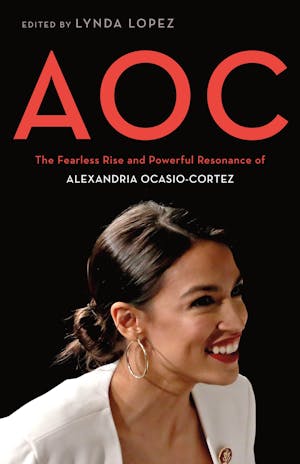

So as someone who intimately knows where she is from, and as a reporter and journalist, I recognized that her significance went beyond her as Personality or Famous Politician. Her win, coupled with her wildly impressive social media savvy, was enabling her to force the media to cover and politicians to address some of the most pressing—and most pushed aside—issues of our time, including poverty, gender and racial economic disparities, massive and unsustainable income inequality, and the urgency around environmental issues. And the communities most affected by those issues responded to her. But particularly, for Latina women who watched her get sworn into Congress standing next to her mother and brother, with her hoop earrings, red lipstick, and dark hair swept back, there was a swell of power, positivity, and pride.

But AOC is not just culturally symbolic. She is a symbol meeting a moment, a particular American moment that is massively important to communities not used to having their voices heard. Her unabashed willingness to take up space, stand in her power, and speak loudly for the underserved and underprivileged, makes her a standout to those communities—and also in Washington. Maria Teresa Kumar, founder of Voto Latino, notes that AOC is one of the most effective communicators in D.C. “I don’t think she’s just changed the conversation in the country, she’s helping define it. No one in the country doesn’t know what the Green New Deal is. That is not small. And for her to do that out of the gate, less than three months into her congressional seat, again, not small.” AOC’s ability to communicate her aspirational legislation, and move people to join her, like Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, who agreed to sponsor the Green New Deal with her, is one of the factors that make her so significant in national politics now. And Kumar says that it’s not just her biggest or most far-reaching policies and proposals that made her a force from the beginning; it’s the smaller ones, as well.

AOC’s insistence on a living wage for her congressional staff, Kumar believes, was transformational. “I used to be a congressional staffer. When I got to Congress, I was earning so little … that I was considering taking on another job. That sounds fine, except when you’re a legislative aid, you might work until 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning. I was getting paid so little that I qualified for low-income housing. A starting salary of $54,000 a year (for AOC’s staff) is not only a living wage, it allows someone of my background, who did not have connections, to be at the table. It allows for you not to be shut out of the market because you actually couldn’t do it, financially. That is not small.

“A lot of the young people who are on Capitol Hill are subsidized by their parents. That was never an option for me. AOC, all of a sudden, created a real meritocracy by allowing anyone to apply, regardless of zip code.”

Simply observing some of these aspirational and far-reaching policy goals of AOC’s would be worthy of an entire book. The fact that she is a Puerto Rican woman representing her district in Congress is also noteworthy—even after the 2018 midterm elections ushered in record numbers of women and people of color, the number of women in Congress only rose by 3 percent. But most significantly, AOC matters because she rose at this moment in our country’s story and discourse.

Latinos in the United States have always known discrimination. They have always experienced prejudice. But particularly in the administration during which Ocasio-Cortez was sworn in, it is not an overstatement to say that Latinos feel under a new kind of attack—one that starts from the top, from a president who refused to decry white nationalists, who spews at best xenophobic and at worst racist diatribes against entire communities of color. From anti-Latino rhetoric targeted at immigrants, to a policy of child separations at the southern border, to being targeted in mass shootings at a Walmart, the climate that has been created for Latinos is one of fear, of being seen as Other. That climate makes it all the more significant that a young working-class Puerto Rican woman from the Bronx has become the most visible and effective new voice in politics. To dismiss or diminish her (as critics, including the president, do) is to ignore something larger and more meaningful that she represents.

It seems fitting, then, to explore the significance of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez now, to look not only at her politics and context but also at her deeper impact. The essays in AOC check in with people from the communities to whom she has meant the most, and truly range from the personal to the political. Rebecca Traister notes that in Congress, AOC is exerting the same power as a man—and a woman who governs like a man is a perceived threat, around whom all manner of negative narrative can spring. Keegan-Michael Key celebrates AOC’s passion and fighting spirit. Nathan Robinson discusses why a label of “democratic socialism” has a slightly different meaning to young people and millennials like Ocasio-Cortez, while Patricia Reynoso writes about feeling as if other Latinas who succeeded didn’t come from the same place she did—until AOC appeared. Erin Aubry Kaplan notes that it took courage for AOC to dance unapologetically outside her congressional office after some tried to ridicule her for a college dancing video that had gone viral, and that same courage is required when talking about race and color in politics. Pedro Regalado writes about the long and rich history of Puerto Rican activism in AOC’s native New York City, while Wendy Carrillo tells of how witnessing the Dakota Access Pipeline protest at Standing Rock was critical to her and to AOC running for office. Natalia Sylvester speaks of how she realized that the imperfect bilingualism she shares with AOC is a beautiful superpower—after a lifetime of being embarrassed by it. Carmen Rita Wong writes about the boldness and braveness it takes, as a Latina, to speak truth to power in the financial realm, and Tracey Ross discusses how AOC highlights the conversation about poverty—and the people it affects. Longtime environmental activist Elizabeth Yeampierre writes about AOC’s willingness to listen to criticism and how that makes her a unique politician. Journalist Mariana Atencio observes the power of AOC’s social media savvy and how she puts it to use. Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodriguez talks about how hard it can be to be indignant, like herself and this new millennial congresswoman. María Christina (MC) González Noguera shares her own story to illustrate the importance of the ties between Puerto Rico and its citizens here in the U.S., as represented by leaders like AOC. Jennine Capó Crucet simply penned an open letter to the congresswoman, an appreciation. And Andrea González-Ramírez gives the primer, the origin story of AOC, from her early life to her historic congressional win, and beyond.

I recently remembered that the night Ocasio-Cortez won her primary, my father had texted me and my two sisters together. He typed just two words: “Alexandria won!” I had no idea before this that my dad, who now lives on the West Coast, even followed what was happening politically in our old neighborhood, nor had he mentioned that he was aware of the race. And though he said nothing else, we all three knew exactly what he meant—a young woman, who was from the same place where he raised his three daughters, had defeated the powerful machine that protected the kind of leadership he had always known there. It meant that we are were moving in a direction my dad had dreamed of for nearly all of his almost 80 years—toward a better place than where our country has been recently. And though he knew as well as we did that AOC’s story had only just begun, and there would be many steps, good and bad, for her along the way, he wanted us to know how happy he was that we had all (including Alexandria) dreamed big. He knew we had had no choice.

Copyright © 2020 by Lynda Lopez