PART ONESPRING

1946

STANCE

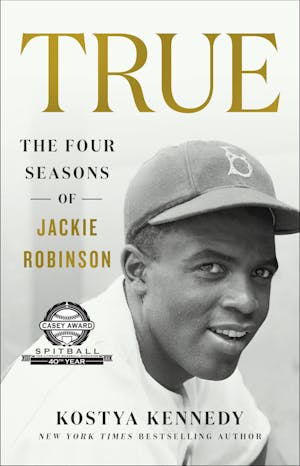

Back then, over the years of his career and after he retired, certain attention was paid to the way Jackie Robinson stood at the plate. His stance. He held his hands high, though not extravagantly so, and he gripped his bat all the way down at the end of its handle, his left pinkie wrapped loosely around the knob. He would wag the bat—34 inches, 35 ounces, of blond ash turned by hand in Louisville, Kentucky—straight up and down, a short range of motion on either side of a 45-degree angle to the earth. Robinson kept his arms back and away from his body, as if, perhaps, he were about to squeeze something waterlogged that might drip on him. He did not waggle his fingers or work his palms on the wood. His grip was firm and constant. He was a right-handed batter, and extremely dangerous.

Robinson kept his hips and backside taut and motionless when he was up at the plate, his left side turned just outward toward third base. He did not bend his knees, at least not to any measure perceptible to those watching him, nor did he crouch forward above the belt. He stood straight, and from instep to shoulder there emerged, as he settled in, a strong feeling of the implacable. Robinson was not quite rigid at the plate—there was too much warm flesh, too much life coursing through him for that. But he was solid standing there, exceptionally solid, and not likely to be moved. A sculpted pillar. Even in his first years of professional ball, at ages twenty-seven, twenty-eight, Robinson was thicker than you might have thought, a football player’s cruel, purposeful body draped now in the thick, loose-fitting flannel of his Dodger grays. He tended toward the back of the batter’s box, duckfooted, his legs more than shoulder width apart and the whole of him ever so slightly crowding the plate. There was an intensity to every element of that stance, an energy—or what opposing pitchers might correctly have observed as a kind of directed menace.

It was a unique batting stance, of course, as all batting stances are. But it was not excessive in any of its particulars. Nor was it unusual in the way of some other batting stances. Stan Musial, for example, stood hunched over at the top of his back, his red Cardinals cap like the bloom of a rare narcissus. Ted Williams, despite his almost clinical manner in the box, proved curiously coiled. Joe DiMaggio stood quiet, poetic even. Willie Mays seemed to be scrambling around when he was up there, all anticipation, while the way that Yogi Berra rested his bat on his shoulder leant a languidness to it all. These were a few of the other great hitters in Robinson’s time.

Yet Robinson’s batting stance may have been the most notable and influential of them all. Throughout his career—early on, certainly, as well as later, even beyond his retirement—it became the most imitated baseball batting stance in the world. In those crucial years in the middle of the twentieth century, America—relieved, proud, post-traumatized—was moving headlong past World War II and at the same time trying to lurch forward, out of the grips of its worst and grimmest sin, to find a way to bend the arc of its own moral history toward justice. The experience of the war was material both to the appetite for change and the resistance to it.

And if the struggle for justice, for sanity, was centuries old in America—beginning with the unheeded cries of the earliest abolitionists and coursing through the Civil War—this was now a new movement, a new soon-to-be definable era. The purpose and intent with which Jackie Robinson played, and with which he and his wife, Rachel, lived, were inevitably, inextricably, and manifestly entwined with the fact that he was the first. The first in baseball, America’s class-blurring milieu. He and Rachel began their journey before the modern civil rights movement found its full-throated voice. On the day that Robinson broke into the major leagues, Martin Luther King Jr. was eighteen years old and had yet to deliver his first sermon.

Robinson gave people, young people and children crucially among them, something physical to regard and emulate. God, he looked good up there. Confident, at ease. They mimicked his batting stance in Florida and Alabama and Georgia, and in California on the campus of UCLA, where Robinson had played college football, and they mimicked him on the streets of the boroughs of New York. Some had seen him in Brooklyn or in Daytona Beach or, as time went on, in any of the towns where Jackie and the Dodgers appeared on the road. Others did their best to co-opt the batting stance despite having only seen Robinson on a snippet of film or in a photograph—or not having seen him at all, but simply copying another child’s rendition. It was one thing to emulate DiMaggio or Williams or later Mays, and another still to be up there, standing just so on a sandlot or stickball court, waiting for a schoolmate’s pitch, and thinking, Oh, what it would be like to be Jackie Robinson up at bat!

* * *

There is one other aspect of Jackie’s batting stance to consider, and for all the other elements, this is perhaps most important: the way that he looked out, from his squared, handsome, unyielding face, with its solid cheekbones and solid chin, and a jaw you couldn’t miss. His left ear was prominent and unprotected in that time before baseball adopted the batting helmet and the earflap—both of which Robinson could have used. His cap, and his alone among the hundreds of players in the game, was fortified by a lining of thick cloth and fiberglass, a minimal defense against the pitches that came toward his head, thrown with intent.

Robinson’s lips tended to purse as he awaited a pitch, his nose showed a crease in its bridge, and his eyes stared straight out with an uncompromising focus on the mound. His brows thick, his forehead furrowed. It was this very gaze—“the look that meant he was ready and all business,” as his teammate Ralph Branca would say many years later—that Robinson fixed on a six-foot-four-inch left-handed minor leaguer, the Jersey City Giants’ hard-throwing and square-jawed Warren Sandel, in the top of the first inning of an early afternoon game on April 18, 1946, the day Robinson, a rookie with the visiting Montreal Royals, officially began his soul-shifting, nation-bending baseball career.

MONTREAL

The land reaches northward off the base of the great continent and leans east into the North Atlantic, its shores protected here and again by outer islands, its modern shipyards secure, the whale-rich waters of the open ocean calming in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and then once more in the inner bay, where the waves finally come up against the rocky, thick thumb of risen land—the Gaspé Peninsula.