Book details

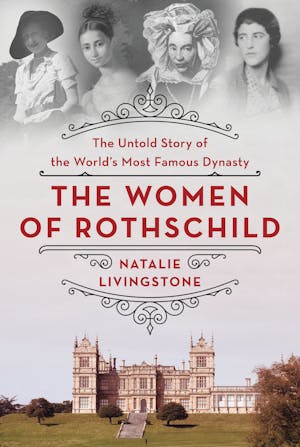

The Women of Rothschild

The Untold Story of the World's Most Famous Dynasty

Author: Natalie Livingstone

About This Book

Book Details

In The Women of Rothschild, Natalie Livingstone reveals the role of women in shaping the legacy of the famous Rothschild dynasty, synonymous with wealth and power.

From the East End of London to the Eastern seaboard of the United States, from Spitalfields to Scottish castles, from Bletchley Park to Buchenwald, and from the Vatican to Palestine, Natalie Livingstone follows the extraordinary lives of the Rothschild women from the dawn of the nineteenth century to the early years of the twenty-first.

As Jews in a Christian society and women in a deeply patriarchal family, they were outsiders. Excluded from the family bank, they forged their own distinct dynasty of daughters and nieces, mothers and aunts. They became influential hostesses and talented diplomats, choreographing electoral campaigns, advising prime ministers, advocating for social reform, and trading on the stock exchange. Misfits and conformists, conservatives and idealists, performers and introverts, they mixed with everyone from Queen Victoria to Chaim Weizmann, Rossini to Isaiah Berlin, and the Duke of Wellington to Alec Guinness, as well as with amphetamine-dealers, suffragists and avant-garde artists. Rothschild women helped bring down ghetto walls in early nineteenth-century Frankfurt, inspired some of the most remarkable cultural movements of the Victorian period, and in the mid-twentieth century burst into America, where they patronized Thelonious Monk and drag-raced through Manhattan with Miles Davis.

Absorbing and compulsive, The Women of Rothschild gives voice to the complicated, privileged, and gifted women whose vision and tenacity shaped history.

Imprint Publisher

St. Martin's Press

ISBN

9781250280190