I

What Is Hope?

Whisky and Swahili Bean Sauce

It was the night before we were to begin our dialogues. I was nervous—because the stakes were high. The world seemed to need hope more than ever, and in the months since reaching out to Jane to ask if she wanted to share her reasons for hope in a new book, the subject of hope had been uppermost in my thoughts. What is it? Why do we have it? Is hope real? Can hope be cultivated? Is there really hope for our species? I knew my role was to ask the questions we all wrestle with as we experience adversity and even, at times, despair.

Jane is a global hero who has traveled the world for decades as a messenger of hope, and I was eager to understand her confidence in the future. Equally, I wanted to know how she had sustained hope during her own challenging and pioneering life.

As I was eagerly and anxiously preparing my questions, the phone rang.

“Would you like to come around for dinner with the family?” Jane asked. I had just landed in Dar es Salaam, and I told her I would be delighted to join her and meet her family. It would be a chance not just to meet the icon but to see her as mother and grandmother; to break bread; and, as I suspected, to sip whisky.

Finding Jane’s house is not easy, as there is no real street address. It is down a number of dirt roads and next to the large compound of Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania. I was afraid I might be late as the taxi tried unsuccessfully to find the right entrance in the tree-covered neighborhood. The red sun was descending quickly and there were no streetlights to guide us.

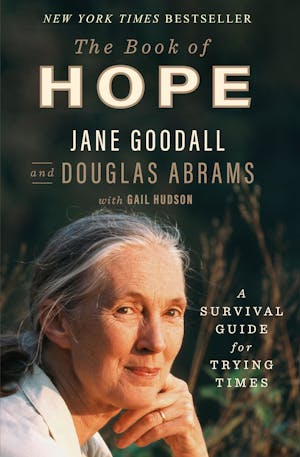

When we finally found the house, Jane greeted me at the door with a warm smile and wide, penetrating eyes. Her gray hair was pulled back in a ponytail, and she wore a green button-down shirt and khaki pants, which looked a little like the uniform of a park ranger. On her shirt was a logo for the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) with the symbols of the organization: a profile of Jane, a chimpanzee knuckling on all fours, a leaf for the environment, and a hand for the humans that she has come to realize need protection along with the chimps.

Jane is eighty-six, but inexplicably she doesn’t seem to have aged very much since she first went to Gombe and graced the cover of National Geographic. I wondered if there is something about hope and purpose that keeps one endlessly young.

But what stands out most is Jane’s will. It shines from her hazel eyes like a force of nature. It is the same will that first moved her halfway around the globe to study animals in Africa and has kept her traveling for the last thirty years. Before the pandemic, she was spending more than three hundred days a year lecturing about the risks of environmental destruction and habitat loss. Finally, the world is starting to listen.

I knew that Jane liked her evening whisky and had brought her a bottle of her favorite, Green Label Johnnie Walker. She graciously accepted it—but later she told me I should have bought the cheaper one, Red Label, and donated the extra money to her environmental organization, the Jane Goodall Institute.

In the kitchen, Maria, her daughter-in-law, had prepared a Tanzanian vegetarian meal. There was coconut rice served with a creamy Swahili bean sauce; lentils and peas with a hint of ground peanuts, curry, and coriander; and sautéed spinach. Jane says she cares nothing about food, but I can’t say the same and my mouth was already beginning to water.

She placed my little gift on the counter next to a giant, four-and-a-half-liter bottle of Famous Grouse whisky. Jane’s adult grandchildren had gotten it for her as a surprise, and they explained that it was so much cheaper to buy in bulk and would surely last for the time she would be with them. Her grandchildren live in the house in Dar es Salaam where Jane moved when she married her second husband, though in those days most of her time was still spent in Gombe. Now Jane spends time in the house only during her short twice-a-year visits to Tanzania and only for a few days at a time, as she also goes back to Gombe and other towns in Tanzania.

For her, an evening tot of whisky is a nightly ritual and an opportunity to relax and, when possible, toast with friends.

“It all started,” she explained, “because Mum and I always shared a ‘wee dram’ every evening when I was at home. So we went on raising a glass to each other at 7 p.m. wherever I was in the world.” She has also found that when her voice gets really tired from too many interviews and lectures, a small sip of whisky tightens the vocal cords and enables her to get through a lecture. “And,” said Jane, “four opera singers and one popular rock singer have told me that this works for them, too.”

I sat next to Jane at the outdoor table on the veranda as she and her family laughed and told stories. The thick bougainvillea surrounding us almost felt like a forest canopy in the candlelight. Merlin, her eldest grandson, was twenty-five years old. Years earlier, when he was eighteen, after a wild night with friends he had dived into an empty swimming pool. He was left with a broken neck, and the injury had caused him to change his life, to give up partying, and, like his sister Angel, follow his grandmother into conservation work. Jane, the understated matriarch, sat at the head of the table, her pride clearly evident.

With my family in Dar es Salaam. Left to right: grandson Merlin; his half brother Kiki, son of Maria; my grandson Nick, half brother to Merlin; granddaughter Angel; and my son Grub. (JANE GOODALL INSTITUTE/COURTESY OF THE GOODALL FAMILY)

Jane put mosquito repellent on her ankles and we joked that the mosquitos were not vegetarians. “Only the female sucks blood,” Jane pointed out. “The males just live off nectar.” Through the eyes of the naturalist, the bloodsucking mosquitoes were simply mothers who were trying to get a blood meal to feed their offspring. That didn’t quite change my dislike of these historic foes of humanity, however.

Angel is working with our Roots & Shoots program and Merlin is helping to develop an education center in an ancient remnant forest near Dar es Salaam. (K 15 PHOTOS/FEMINA HIP)

As the conversation and family stories paused, I wanted to ask Jane the questions that had been absorbing me ever since we first decided to collaborate on a book about hope.

As a born-and-raised and somewhat skeptical New Yorker, I had to admit that I was suspicious of hope. It seemed like a weak response, a passive acceptance—“let’s hope for the best.” It seemed like a panacea or a fantasy. A willful denial or blind faith to cling to despite the facts and the grim reality of life. I was afraid of having false hope, that misguided imposter. Even cynicism felt safer in some ways than taking the risk of hope. Certainly, fear and anger seemed like more useful responses, ready to sound the alarm, especially during times of crisis like this.

I also wanted to know what the difference was between hope and optimism, whether Jane had ever lost hope, and how we keep hope in dark times. But these questions would need to wait until the next morning, as it was getting late and the dinner party was breaking up.

Is Hope Real?

When I returned the next day—a little less nervous—to begin our conversation about hope, Jane and I sat on her veranda in old, sturdy wooden folding chairs with green canvas seats and backs. We looked out at the backyard so filled with trees that it was almost impossible to see the Indian Ocean just beyond. A chorus of tropical birds sang, screeched, cackled, and called. Two rescue dogs came to curl up at Jane’s feet, and a cat meowed through a screen, insistent about contributing to the conversation. Jane seemed a little like a modern-day Saint Francis of Assisi, surrounded by and protecting all the animals.

“What is hope?” I began. “How do you define it?”

“Hope,” Jane said, “is what enables us to keep going in the face of adversity. It is what we desire to happen, but we must be prepared to work hard to make it so.” Jane grinned. “Like hoping this will be a good book. But it won’t be if we don’t bloody work at it.”

I smiled. “Yes, that is definitely one of my hopes, too. You said that hope is what we desire to happen, but we need to be prepared to work hard. So does hope require action?”

“I don’t think all hope requires action, because sometimes you can’t take action. If you’re in a cell in a prison where you’ve been thrown for no good reason, you can’t take action, but you can still hope to get out. I’ve been communicating with a group of conservationists who have been tried and given long sentences for putting up camera traps to record the presence of wildlife. They’re living in hope for the day they’re released through the actions of others, but they can’t actually take action themselves.”

It sounded like action and agency were important for generating hope, but that hope could survive even in a prison cell. A black cat with a white chest strolled out of the house and onto the balcony and jumped in Jane’s lap, curling up comfortably, his paws tucked under him.

“I’m wondering if animals have hope.”

Jane smiled. “Well, when Bugs here,” she said, petting the cat, “was sitting inside all that time, I suspect he was ‘hoping’ that eventually he would be let out. When he wants food, he gives plaintive meows and rubs against my legs with arched back and waving tail, as this usually produces the desired effect. I’m sure when he does that he’s hoping he will be fed. Think of your dog waiting in the window for you to come home. That’s clearly some form of hope. Chimps will often throw a tantrum when they don’t get what they want. That is some form of frustrated hope.”

It seemed like hope was not uniquely human, but I knew we’d return to what made hope unique in the human mind. For now, I wanted to understand how hope was different from another term with which it is often confused. “Many of the world’s religious traditions talk about hope in the same breath as faith,” I said. “Are hope and faith the same?”

“Hope and faith are very different, aren’t they,” Jane said, more as a statement than a question. “Faith is when you actually believe there is an intellectual power behind the universe, which can be translated into God or Allah or something like that. You believe in God, the Creator. You believe in life after death or some other doctrine. That’s faith. We can believe that these things are true, but we can’t know. But we can know the direction we want to go and we can hope that it is the right direction. Hope is more humble than faith, since no one can know the future.”

“You were saying that hope requires us to work hard to make what we want to happen actually happen.”

“Well, in certain contexts it is essential. Take this dire environmental nightmare we are living in today. We certainly hope that it is not too late to turn things around—but we know that this change will not happen unless we take action.”

“So by being active, you become more hopeful?”

“Well, you have it both ways. You won’t be active unless you hope that your action is going to do some good. So you need hope to get you going, but then by taking action, you generate more hope. It’s a circular thing.”

“So what actually is hope—an emotion?”

“No, it’s not an emotion.”

“So what is it?”

“It’s an aspect of our survival.”

“Is it a survival skill?”

“It’s not a skill. It’s something more innate, more profound. It’s almost a gift. Come on, think of another word.”

“‘Tool’? ‘Resource’? ‘Power’?”

“‘Power’ would do. ‘Power’—‘tool.’ Something like that. Not a power tool!”

I laughed at Jane’s joke. “Not a drill?”

“No, not an electric drill,” Jane said, laughing, too.

“A survival mechanism…?”

“Better, but less mechanical. A survival…” Jane paused, trying to come up with the right word.

“Impulse? Instinct?” I offered.

“Actually, it’s a survival trait,” she finally concluded. “That’s what it is. It is a human survival trait and without it we perish.”

If it was a survival trait, I wondered why some people had more of it than others, if it could be developed during particularly stressful times, and whether she had ever lost it.

Have You Ever Lost Hope?

Jane has a rare blend of qualities—a scientist’s unflinching willingness to face the hard facts and a seeker’s desire to understand the most profound questions of human life.

“As a scientist, you—” I began.

“I consider myself a naturalist,” she corrected.

“What’s the difference?” I had always assumed a naturalist was simply a scientist who went out into the field.

“The naturalist,” Jane said, “looks for the wonder of nature—she listens to the voice of nature and learns from nature as she tries to understand it. Whereas a scientist is more focused on facts and the desire to quantify. For a scientist, the question is, ‘Why is this adaptive? How does it contribute to the survival of the species?’

“As a naturalist, you need to have empathy and intuition—and love. You’ve got to be prepared to look at a murmuration of starlings and be filled with awe at the amazing agility of these birds. How do they fly in a flock of several thousand without touching at all, and yet have such close formations, and swoop and turn together almost as one? And why do they do it—for fun? For joy?” Jane looked up at the imagined starlings, and her hands danced as if they were a flock of birds rippling through the sky.

Copyright © 2021 by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams