1

It had been years since I’d searched for my cousin. In the early days, I entered fringe-style message boards with a feverish enthusiasm, hoping to find lost girls but more often than not finding derelicts who hoped I was a lost girl, who asked things like whether I was tight or loose long before I knew how those words might apply to my anatomy. Sometimes I’d ask to be dropped at the mall, where I’d comb the shops I thought she’d like, lingering for hours over scents at Bath & Body Works, debating whether she’d like peach or raspberry, before stalking the aisles of Hot Topic.

It plagued me constantly, then, that I didn’t know what she’d become. I imagined all sorts of variations on Andrea: Goth Andrea with pink and green hair and fishnets and a deep love for Joy Division; Andrea who snuck out to kiss older boys on the middle school jungle gym after dark; Andrea who mastered a fouetté and went on to perform at the Palais Garnier. It drove me mad, not knowing. More so than not having her in my life, maybe. It was the lack of connection to who she was, the absence of noise where I’d once been able to read her thoughts almost as easily as my own.

Patty and Tom—my adoptive parents—might have known what I was up to or might not have. Patty had a strict rule: No dwelling in the past. What’s done is done. Put one foot in front of the other. Et cetera. To her, that meant no talking about anything that happened before I came into their home. She was desperately afraid I’d be perceived as abnormal, and in the way she fretted, I knew I must be. But Tom was the one who most often drove me to those solo outings, and sometimes the look he gave me when he dropped me off was so nakedly pitying and sweet that I’d have to jump quickly out of the car with hardly a good-bye in order not to cry.

When Facebook finally went wide, I scanned endless pages of anonymous profiles. Every time I saw a girl who looked like me, I clicked, leading to a string of dead ends. Same with Google. My late teens and early twenties were spent skipping parties to stay in and search “Andrea Indiana” and “Andrea Mother Collective” and “cult bust 1990s kid survivors” and a million other iterations of the same damn things. My college roommates would stumble in at five a.m., lipstick smeared, eyes glazed, limbs weak and trembling from dancing, and I’d still be sitting there at my desk. Searching obsessively.

My whole life revolved around Andrea, and Andrea wasn’t even there.

One day I spit in a cup and mailed it in to one of those DNA websites. When that didn’t yield results, it occurred to me to ask the social worker who had been on my case. It seemed so obvious a solution that when I thought of it, I laughed aloud. After that didn’t turn up any results, I gave up. Andrea had disappeared altogether, lost to the foster care system. With no last name or birth certificate, she may as well have ceased to exist the night I tossed a metaphorical grenade into the center of our childhoods.

It wasn’t what I’d intended, of course. As an adult, I have realized that the biggest mistakes usually aren’t intentional so much as idiotic and tragically avoidable. One little error. A misguided tweet, a rogue email, a forgetful, harried disposition and your reputation is ruined, you’ve lost your job, you’ve left your child in the back of the car on a hot day.

It was the start of summer, a Saturday. I had my window open and a soft breeze was filtering through the screen. The piece of tape I’d used to patch it had come dislodged and was flapping around. A mosquito had found its way in and drunk heavily from my left shoulder before I noticed and squashed it, spreading a fine streak of blood across my palm. I’d been editing a manuscript and fighting off drowsiness with Skittles and Diet Coke. I intermittently scrolled through Twitter, following a viral debate over whether Taylor Swift, at thirty, ought to consider having babies before her looks faded and all her eggs turned to dust.

Working well into the weekend evenings, when everyone else was presumably out living their full, rich lives, had become typical for me aside from an occasional happy hour invitation from my supervisor, Elena. Ryan—the guy I’d been hooking up with—worked weekends at a bar, and most other people I knew disappeared at five p.m. Friday, receding into the glow of their relationships and family lives just as I receded into the glow of my computer screen. On the plus side, weekend hibernation saved me money—or rather, prevented me from sinking further into debt. The negative side, of course, was that it made me acutely aware of having nowhere to go.

I’d once been one of the kids Ryan catered to at the bar. I knew the game too well—was intimately familiar with the thin border between adolescence and adulthood. It was how I’d met him myself—drinking to casual oblivion as I began to cross that very threshold. Mine was a neighborhood for youths, artists, and leftovers. As one of the thirtysomethings who still lived there, I fell into the “leftover” category, though it could have been worse. It could have been a neighborhood populated by pregnant women, nannies, and strollers. I’d graduated from a vibrant, hopeful twentysomething with an alluringly blank future to what I was now—an adult with little to show for it other than a job and a cramped, dingy studio apartment.

The radiator in said apartment was inconsistent, and when it worked it was so hot to the touch it had actually given me a scar once. The second-floor light outside my unit turned off and on at a whim, and more often than not I had to fumble my way home in the dark. The refrigerator worked—kind of—except for the condensation that gathered up top, never falling, like hundreds of small stalactites. I slept on a mattress a former roommate had handed down when she moved in with her boyfriend; all other décor consisted mostly of street finds. The only thing I ever splurged on—my one concession to vanity—was the set of hair extensions I replaced each month to cover the alopecia I’d had since I was a kid.

Even the large canvas that graced the wall above the patio set I’d repurposed as a dining table had been confiscated from a garbage bin outside an artist’s loft during Open Studios. It was a painting of an empty boat, drifting away from its intended occupant, a woman trapped on an island. It was unsigned, and clearly someone hadn’t thought it was very good, but I liked its mood: it had a relentless, lonely sort of beauty to it. I was glad to have saved it. I was proud of all my motley treasures. It was squalor of a kind, but I was comfortable in it. It was my own very small footprint in an oversaturated, overpriced city. Moreover, it was the only proof of progress I could point to.

I toggled fluidly between news headlines, email, and edits on nights like these, when time seemed infinite, so when I saw an email announcing “New DNA Relatives,” it didn’t really register. I absently clicked the See New Relatives button under a message that informed me one new relative had joined in the last thirty-one days.

Every now and then over the years, I’d clicked that same button to find a sixth-plus cousin or to be reminded of the gene mutation that allowed me to smell asparagus in my pee. After more than ten years on the site, I did not expect my one new relative to be Andrea. My Andrea.

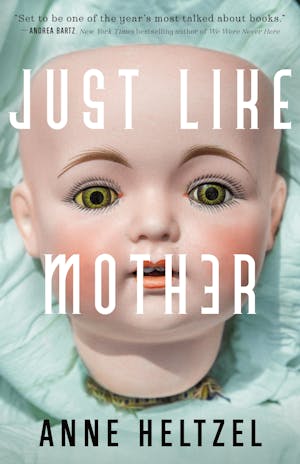

Copyright © 2022 by Anne Heltzel