1

AHEM

Dear reader,

Picture a mute feather woman. She’s essentially a bloodless meerkat recluse working as a night janitor for an apothecary. She does helpful things like apologize to the sun and lie facedown on census day so she’s not on record for being alive. Now ask her to stand in the center of a farmer’s market and pop-belt reasons why she loves herself and should be elected mayor.

This is me writing a book.

To write you a letter listing reasons why you should be interested in my brain is to pour curdled milk on my personal bill of rights, which for years decreed that the shadows and unsent-idea emails were my mental Cheers bar.

But I’m writing a book. I’m writing a book, and the women in my brain are hyperventilating.

Some are in pilled sweaters meaning well, some are building forts or writing terrible poems, some have blood in their teeth and are throwing a cantaloupe through a store window. All of these brainwomen are different. Most of them are afraid. Many of them stand sentry at the door, warning the other women of the dangers of bravery and action. Lipstick for the bodega might send the poisonous message that you love yourself—suggesting that your ideas are worthy is identity suicide. It’s bagpipes at a library. It’s a selfie at a funeral. It would kill us, plead the brainwomen. Leave the hand-raising to the women without cereal in their bra. Delete this paragraph.

Well, that was the first thirty years of my life. Then a strange combination of personal and world events gently then violently shifted my brainwomen, sedating some and birthing others. To my shock, some of the veterans announced their desire to phase out from twenty-four-hour megaphone duty and become a nap-prone member of the board. One woman stood up from leaning against a supply closet and out fell another—bound, gagged, and kicking her pantyhosed legs at the women who’d locked her away.

I feel a shift. There are things we do to protect ourselves as ladies that make sense when we’re twelve or twenty-five, but now with things like retinols and Donalds we no longer need those brainwomen’s help to feel shame. So I’m baking some of those women an Ambien Bundt cake and writing this E. E. Cummings wedding toast of a book to you before they wake up.

Of course, I love those brainwomen, too. Every time they held me back from running at something, I saw a different color of the world. Something I would have missed if I’d ignored them. While many of my braver friends seemed to run with a spear at the horizon, I sat with binoculars and a notebook. And now, before I suddenly throw my computer in an acid bath, I’d like to present my field notes.

* * *

My name is Betty. Sorry, as an actor I’ve been conditioned to exchange deepest fears and traumas before names. If the brain is a house, I like to get right to the terrifying attic and haunted second bathroom of truths and just bypass the vestibule of small talk and boundaries. Don’t worry, this won’t be an actor memoir. I don’t have any delusions that the octogenarian auctioneers who have seen my Off-Broadway theatre canon are clamoring for my childhood timeline. Nor do I think the gentlemen who send me eight-by-ten printouts of my own breasts to sign are petitioning for my book—I’m not aware that they know I can read. But now that there’s been a small brain earthquake and I’m coughing dramatically through the smoke, I see that all my experiences as a sometimes-working actor have been a perfect allegory for being a woman in this world. Having to cycle through identities to give whoever is in front of you the girl they want, feeling like you have to audition for the job you already have, having a quarter of the time that men do to achieve your dreams before your tits are in your shoes and the government deems you disgusting and banishes you to eat sleeves of tear-soaked saltines in bed until you die.

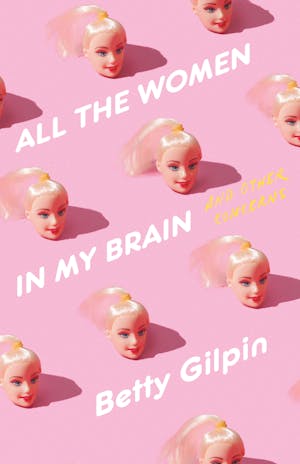

I have been doing actor weirdness professionally for fifteen years. Most of that has consisted of trying. Trying to make smaller my facial expressions, choices, and curves—all of which were too big to play sexy aunt with laundry or slutty neighbor with question. Trying not to listen to the business when it told me the things that were valuable about myself were not my imagination and darkness but my youth and cleavage. Trying not to feel shame for wanting things, and battling the anvil-anklets of depression and anxiety while walking through the world as an apologizing Barbie. Trying.

And then sometimes, in the dead of night, in a hamster-on-deathbed whisper, I do something illegal. Do you? Do you ever wonder if you could … never mind. It’s gross to type.

(TYPE IT, COWARD.)

Listen. I could write a dissertation on the blegh of my face and the suck of my ways. But also of course is that other thing, buried in all the no and sorry.

There is something inside you, and something different inside me, and in Al Roker and Elian Gonzalez and your dentist, that is insane and obscure and extraordinary. And yours. A tiny little pinprick of light. It’s buried under lead bags of fear and oh well. Sometimes you think maybe it doesn’t exist. Its externalization instructions are written in a dead language. Maybe one time you were given the chance to unearth it and let it float out, and nothing happened. You take that as proof it was all in your head, so you never try again. Maybe you’re convinced that unless the world acknowledges your light as extraordinary, then it doesn’t matter. It was never real.

Somewhere along the way I got too tired to hate myself all the time. And looked in the mirror and thought, you fuck, you have to try. I don’t know what it looks like, but there’s something in there that has to come out. Something, to use a horrible word, “special.”

*Have asked publisher to use puke-proof paper*

I am at the point where the caterpillar asks for a pretransformation cigarette break. She briefly wonders if she could turn into an eagle, or instead position herself to get pancaked by a Hyundai. We all have it at some point: the horrific adult realization that no one is going to hold you down, cut you open, and forcibly extract your centimeter-tall scroll of inner magnificence for the world to read. It’s in your hands to decide your fate as magic or sweatpants. What once were personality quirks that made your emails more relatable are now sandbags against the door to potential. So many of us feel like we are designed for Greek circumstances but are given Ikea boxes to put them in. Emotionally, this book is an opportunity to sit together on the floor of Grand Central, turn our purses inside out, and simultaneously shit our pants. (I both know exactly what that means and have also lost the thread.)

No—what I mean is this. So many of us wait until the hallway or journal or car to open the compartment where we hide our ugly and our majesty. I want this book to scalpel out the darkness and ask if it looks like yours. Then I want to coax out the lice-sized brainwoman who believes we are meant for the moon and ask her to speak, too. I want to write about being afraid and grabbing the spear anyway, sobbing and peeing and sprinting at the horizon.

2

SALEM OR BARBIE

Are we ready for more metaphors? Who needs water? Oops, we lost a reader. Bye, Meredith!

* * *

For those left:

Do you ever look at our generation and roar, “Fuck yes!” Then squint at something alarming and whisper, “Oh no.”

Listen—now is great. Feminism is everywhere; feminism is Beanie Babies. You’re welcome! we post. It is, of course, not our welcome to you’re. We modern Braveheart McDormands had very little to do with it. Centuries of women before us whispered no into hoop skirts, then growled it into bloomers, then screamed it braless into megaphones. The whispers and growls and screams were passed down like woke diabetes. Each next little baby girl was born with eyes wider and wider open to her own shackled potential. And now us! The official patriarchy antidote carrier pigeons!

The problem is it’s … well … it’s us.

In my humble, probably wrong, select-all-delete opinion, we womenfolk today are faced with a decision: Salem or Barbie. We can either rip off the internal trapdoor that your Alanis Plath of Arc has been suffocating under or cement over it and instead luxuriate in a Hello Kitty porny Instagram-filtered cell where the validation is better than heroin and the thoughts are shorter than Mickey Rooney. (HEY-OH!) Both chambers exist in the female psyche. Both celebrate polar-opposite qualities of womanness. Both need your help to survive. Both are disgusted by the other. Much of my life is spent frantically commuting between these two chambers. I am terrified that if I don’t maintain a steady to-and-fro, the trapdoor will be sealed forever, and I’ll be stuck on the wrong side. The casual news is each has the power to kill us. So before we choose one, let’s examine the candidates.

* * *

Under the trapdoor within us, the Salem chamber is fucking wild. It is a churning sea of monsters in your gut. It is a frothing black ocean of your fullest, darkest, most terrifying potential. Peer down there and see all of your ancient ancestors screaming poems into the dark waves. Look! There’s a group of sorceresses building a telescope out of your childhood traumas. And there! A she-gargoyle in a bathrobe is writing a song about sixth grade and genocide. OK, wow, she’s giving birth to a knife.

Everywhere here, pain and experience become windows and ideas. Used and fed correctly, this is your superpower. The trapdoor kept open to this part of you means the monsters can make meaningful things that etch your existence into the “who was here” universe log. When used in your relationships, you let yourself feel the full pain and beauty of really knowing someone, and being known. It is spectacular. Open the trapdoor and see the big questions float up to you: Who am I? Who are you? Where is God? Why all this?

As a child, it was easy to be here. As a child, that’s all there was. I swam in it all day. I’m going to run until the recess frost soaks through my Keds, because I’m a rabid justice mercenary! I’m going to use all purples and browns in art today because that’s what my monster soup is screeching for, and I need to see where it goes. I don’t have time to think about the tomato sauce on my face—I’m conducting a séance with a dead mouse. I was a tangled-hair rage angel who screamed, “AYE AYE” from apple trees. I kicked my unshaven legs around like electric spaghetti. I picked my clothes based on colors I liked and what priestess or scallywag I might embody that day. There was no apology, no checkpoint between my brain and the world, to make sure my output was acceptable.

Then it changed.

Slowly but surely inconveniences like tits and trauma peppered themselves into my life, and wearing a lobster pot on my head while charging at an oak tree was no longer socially viable. The monster soup became a complicated place to exist in. I started to see myself from a bird’s-eye view. Betty, when you’re loud, you’re too much. When you wear purple, you’re too much. When you have sauce on your face, it means you’re not invited to Jonah’s bar mitzvah, and that means loneliness. The mirror suddenly became important, something scrappy-warrior-me would only use for the ugly-face game.

Imagination and bravery became less useful as a growing girl. Suddenly life was a point system where things that were once my lifeblood were now worth near zero.

In middle school I realized that not all of my monsters & co. were laughing. Some of them were becoming terrifying. I felt a connection to things that scared me. I sensed a deeper weirder darkness churning that I didn’t understand, huge questions and feelings that I had no tools to address. Instead of wanting to build a mud castle, now the monster soup wanted to explore suffering and existence and the sky.

I was disappointed to see there was no time for those things. It became apparent that my highest purpose as a twelve-year-old girl was not to ask questions and externalize the weird to see where it led but instead to soften and cutesify my identity to submit for acceptance. I had been wrong: I was not an alchemist. I was a tank top.

So I began heartbreaking internal renovations. I let the monsters know that while I so valued their contribution to my multicolored feast of a life, I saw it was safer for them to be muted. Avoiding eye contact with a gorgon, I closed the trapdoor.

On top of that trapdoor, I did what girls have to do. I built the Barbie cell.

The Barbie cell is a checkpoint between your power and the world, a filter between your weird and the cafeteria. Here your dreams and sentences that drift up from the gremlins who once designed your playdates are now passed through the trapdoor and vetted in this cell; picked over for ugly; scrubbed clean of the dangers of idiosyncrasy, volume turned down; and sent out into the world with an apology disclaimer. Sure, sometimes you open the trapdoor and dip into the monster soup alone in your room or with a rare friend whose cardigan you’re not copying; but otherwise, the Salem chamber is suddenly useless.

Useless, and sometimes just … too painful. It’s not always fun to keep the trapdoor open. It means listening to music that makes you remember things you’d rather not. It means getting through the book that’s making your brain light up with imagery but Jesus God this chapter is a boring downer. It’s watching the news to stay connected to the immense need of the whole world, which can be an impossible idea to hold in your brain while holding a pointless latte in your hand.

Keeping the trapdoor open means being uncomfortable and uncertain. It means treating the world as a question and yourself as a worthy seeker of answers. That can be wholly terrifying. Or immensely depressing. Or honestly? Just … boring. The modern attention span combined with our learned shame is a perfect excuse not to open the trapdoor that day. Who am I to be a sorceress? I don’t want to swim in the needle-water of my full capacity of aliveness today. I’d like to be a little less sad and work a little less hard. I don’t want to know myself—I don’t love what I’ve got so far.

The solution is the Barbie cell.

Sitting on top of the trapdoor is a room where everything’s easy. The Barbie cell is my pastel, cushioned den of sexy, delicious escape and distraction. Let me show you around. Here Princess Jasmine is making a Sour Patch Kid mosaic out of compliments I’ve received. A gaggle of vocal fry cartoon bunnies discuss aerobics and jeans. Over on the waterbed, a human cupcake scrolls Twitter, copying down opinions for me to recycle as my own at a dinner party, thereby rescuing me from the excruciating tedium of original thought. Over here a montage of kittens and my own achievements plays on a loop for me to escape to when my lunch partner is detailing their mother’s illness: the vulnerability of a situation I can’t control is painful and boring! Top-40-forget-life music is pumped in through Brazilian-waxed speakers—certainly no song with an actual instrument or thesis statement that would stir a memory and crack open the trapdoor.

I am tempted to live here forever, filling my brain with cotton candy smoke, smudging out the ugly.

I spent adolescence feeling like a vile dunce leper clawing at any semblance of acceptance. The postpuberty realization that my expirable qualities could achieve an open door or eye contact with little to no work felt like I’d discovered how to frack champagne. Pre-boobs, my journal was filled every night with (illegally bad) poems and emo-crazed paragraphs about What It All Meant. Less so when I realized it was more difficult to weave my journal into my outward identity as a woman, and easier to craft the illusion of a fuckable, trauma-less girl. Easier to stay in the Barbie cell, collect validation points as the cheap way to stay alive and needed, and let the Salem stuff be a secret.

Hide your darkness; show your belly button.

Then in the ultimate act of self-betrayal, I learned how to sell the darkness. I saw I could treat it as fodder for the character the Barbie cell wanted to convince the world I was. Posing with a journal at Starbucks but not actually writing in it. Pulling at my sleeves in performed angst, biting my lip and conjuring a sexy tear so the football player eating an exploded pen across the classroom would deign to consider masturbating to my mystery. The gargoyles and witches in my black ocean chamber wailed in horror as I stopped treating them like the portal to power, but instead a haunted warehouse only accessed when I needed Barbie-cell validation. I refurbished a plastic cutesier version for the vocal-fry princesses upstairs to sell for an eyebrow raise. Like some huckster salesman selling blow-up doll witches on the outskirts of Salem.

The trapdoor threatened to cement over forever.

Making my living as an actress has been a strange, frantic commute between these two chambers. I first became an actor exclusively because of the Salem shit. For most of the time, acting feels like you are an uninvited impostor troll, tap-dancing for an audience who you’re convinced is silently begging you to stop and kill yourself. But every once in a trillion attempts, it feels like glorious haunted church. Reality shifts and your trapdoor is ripped off its hinges, and all the ghosts come out into the room and float. I’m suddenly all the things I was when I was seven, before apologies replaced questions. The monster soup is no longer an abandoned warehouse but a maniacal Amazonian Mardi Gras of ideas and visions. I feel my whole body pulse like a living weapon. And then a cell phone goes off in the audience, and I’m terrible again and the moment is over. But the monsters under the trapdoor are fat with feeding, elated and strong.

Sadly, as an actress, you often are not hired for the ghosty stuff but for the least interesting parts of yourself. The video game dowry qualities. Not for what you’re capable of but for how you adorably seem. You’re not a powerful chameleon interpreter. You are instead to hold a laundry basket or helpful lube near the real story: him.

The pursuit of an acting job involves an inordinate amount of time in the Barbie cell. After a few years of auditioning, I wondered if spending less time on charting the character’s family tree and more time curling my hair would get me more work. (It did.) In drama school, being an actor meant sobbing in pajamas and attempting organ-shifting sorcery, probably with terrible results, but it felt like magic. In the real world, being an actress meant trying to Spanx and paint and squint myself into pretending I have existed forever as a shy little Bond girl who will never age or fart. If I’m lucky, and the fake eyelashes get me the job, I can try to Trojan horse some of the ghosty stuff in on the third take. (They probably won’t use it—too many weird faces.) Every audition is preceded by an hour of panicking about how to make myself less hideous. Every time I step on set it’s after two hours of hair and makeup that morph me into a porny stranger. But it’s the toll I have to pay to get to the monster soup. Get in the room by giving them what they want from the pink fantasy doll suite, then secretly pry open the trapdoor and be Medea with lip gloss.

What scares me is the temptation to stay in the former. As I type, I’m in this millisecond-long intersection of genetics and career where my tits and neck haven’t committed suicide and the entertainment business has briefly deemed me acceptable to hire. It is too terrifying a question to ask the world, Why am I allowed to play the sobbing wife? Is it the writhing witches who conjured the tears, or the perky-for-now tits on which those tears plop?

* * *

It was years of lying in the grass conducting a cloud symphony with tiny dirty toes, then lonely preteen me asking those clouds for answers that made my favorite parts of me. The Barbie cell makes me forget. I get validation-drunk. Looking at a photo of me where my cheeks are artificially rosier and angle-ier, where my lips have been outlined a few centimeters fluffier, where my eyelids look like Van Gogh coughed on each of them and then a family of cashmere caterpillars took a group nap on my lashes and eyebrows, where my hair has been burned and torqued into that of a cartoon pony’s, where my borrowed tailored clothes make me look like I just stepped off a boat where everyone fucks by the cheese plate, where the angle at which I’m standing and trick of the light make me look smaller and younger and my facial expression offers a blow job as a sexy tariff, looking at this photo … feels … so … fucking … good.

(Pause as I funnel Dramamine into Susan B. Anthony’s grave.)

I don’t have a public social media account as an actor. But I have played with death and searched my name on fecalstew.com: Twitter. Since the world spent my adolescence convincing me I was disgusting, now a handful of invisible Wi-Fi-owners deeming me fuckable feels like victory. Giddy from the win, I then open the trapdoor to call up goblins for a scene or an essay, but … wait. They’re all flipping me off, on strike, having been ignored for weeks of lip gloss and self-deprecation. Filming a scene, I used to be able to conjure a creativity witch with a deep breath. Now I have to fight past Barbie-cell members reminding me the priority in this scene is not the fickle pursuit of catharsis but the opportunity to convince the world I’m gorgeous. Using the churning ocean of darkness and imagination within me to ask the universe a question is pointless, the Barbies insist. Much safer to just focus on sucking it in and ask the only question we women need worry about:

Do you love me?

Copyright © 2022 by Betty Gilpin