RATH

It was in the spring that his fosterers the O’Hagans brought Hugh O’Neill to the castle at Dungannon. It was a great progress in the boy Hugh’s eyes, twenty or thirty horses jingling with brass trappings, carts bearing gifts for his O’Neill uncles at Dungannon, red cattle lowing in the van, gallowglass and archers and women in bright scarves, O’Hagans and McMahons and their dependents. And he knew that he, but ten years old, was the center of that progress, on a dappled pony, with a new mantle wrapped around his skinny body and a new ring on his finger.

He kept seeming to recognize the environs of the castle, and scanned the horizon for it, and questioned his cousin Phelim, who had come to fetch him to Dungannon, how far it was every hour until Phelim grew annoyed and told him to ask next when he saw it. When at last he did see it, a fugitive sun was just then looking out, and sunshine glanced off the wet, lime-washed walls of its palisades and made it seem bright and near and dim and far at once, heart-catching, for to Hugh the stone tower and its clay and thatch outbuildings were all the castles he had ever heard of in songs. He kicked his pony hard, and though Phelim and the laughing women called to him and reached out to keep him, he raced on, up the long muddy track that rose up to a knoll where now a knot of riders were gathering, their javelins high and slim and black against the sun: his uncles and cousins O’Neill, who when they saw the pony called and cheered him on.

Through the next weeks he was made much of, and it excited him; he ran everywhere, an undersized, red-headed imp, his stringy legs pink with cold and his high voice too loud. Everywhere the big hands of his uncles touched him and petted him, and they laughed at his extravagances and his stories, and when he killed a rabbit they praised him and held him aloft among them as though it had been twenty stags. At night he slept among them, rolled in among their great odorous shaggy shapes where they lay around the open turf fire that burned in the center of the hall. Sleepless and alert long into the night he watched the smoke ascend to the opening in the roof and listened to his uncles and cousins snoring and talking and breaking wind after their ale.

That there was a reason, perhaps not a good one and kept secret from him, why on this visit he should be put first ahead of older cousins, given first choice from the thick stews in which lumps of butter dissolved, and listened to when he spoke, Hugh felt but could not have said. Now and again he caught one or another of the men regarding him steadily, sadly, as though he were to be pitied; and again, a woman would sometimes, in the middle of some brag he was making, fold him in her arms and hug him hard. He was in a story whose plot he didn’t know, and it made him the more restless and wild. Once when running into the hall he caught his uncle Turlough Luineach and a woman of his having an argument, he shouting at her to leave these matters to men; when she saw Hugh, the woman came to him, pulled his mantle around him and brushed leaves and burrs from it. “Will they have him dressed up in an English suit then for the rest of his life?” she said over her shoulder to Turlough Luineach, who was drinking angrily by the fire.

“His grandfather Conn had a suit of English clothes,” Turlough said into his cup. “A fine suit of black velvet, I remember, with gold buttons and a black velvet hat. With a white plume in it!” he shouted, and Hugh couldn’t tell if he was angry at the woman, or Hugh, or himself. The woman began crying; she drew her scarf over her face and left the hall. Turlough glanced once at Hugh, and spat into the fire.

Nights they sat in the light of the fire and the great reeking candle of reeds and butter, drinking Dungannon beer and Spanish wine and talking. Their talk was one subject only: the O’Neills. Whatever else came up in talk or song related to that long history, whether it was the strangeness—stupidity or guile, either could be argued—of the English colonials; or the raids and counter-raids of neighboring clans; or stories out of the far past. Hugh couldn’t always tell, and perhaps his elders weren’t always sure, what of the story had happened a thousand years ago and what of it was happening now. Heroes rose up and raided, slew their enemies, and carried off their cattle and their women; O’Neills were crowned ard Rí, High King, at Tara. There was mention of their ancestor Niall of the Nine Hostages and of the high king Julius Caesar; of Brian Boru and Cuchulain, who lived long ago, and of the King of Spain’s daughter, yet to come; of Shane O’Neill, now living, and his fierce Scots redshanks. Hugh’s grandfather Conn had been an Ò Neill, the O’Neill, head of his clan and its septs; but he had let the English dub him Earl of Tyrone. There had always been an O’Neill, invested at the crowning stone at Tullahogue to the sound of St. Patrick’s bell; but Conn O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, had knelt before King Harry over the sea, and had promised to plant corn, and learn English. And when he lay dying he said that a man was a fool to trust the English.

Within the tangled histories, each strand bright and clear and beaded with unforgotten incident but inextricably bound up with every other, Hugh could perceive his own story: how his grandfather had never settled the succession of his title of an Ò Neill; how Hugh’s uncle Shane had risen up and slain his own half-brother Matthew, who was Conn’s bastard son and Hugh’s father, and now Shane called himself the O’Neill and claimed all Ulster for his own, and raided his cousins’ lands whenever he chose with his six fierce sons; how he, Hugh, had true claim to what Shane had usurped. Sometimes all this was as clear to him as the branchings of a winter-naked tree against the sky; sometimes not. The English … there was the confusion. Like a cinder in his eye, they baffled his clear sight.

Turlough Luineach tells with relish: “Then comes up Sir Henry Sidney with all his power, and Shane? Can Shane stand against him? He cannot! It’s as much as he can do to save his own skin. And that only by leaping into the Blackwater and swimming away. I’ll drink the Lord Deputy’s health for that, a good friend to Conn’s true heir…”

Or, “What do they ask?” a brehon, a lawgiver, states. “You bend a knee to the Queen, and offer all your lands. She takes them and gives you the title Earl—and all your lands back again. Surrender and regrant,” he said in English: “You are then as her urragh, but nothing has changed…”

“And they are sworn then to help you against your enemies,” says Turlough.

“No,” says another, “you against theirs, even if it be a man sworn to you or your own kinsman whom they’ve taken a hatred to. Conn was right: a man is a fool to trust them.”

“Think of Earl Desmond, imprisoned now in London, who trusted them.”

“Desmond is a thing of theirs. He is a Norman, he has their blood. Not the O’Neills.”

“Fubún,” says the blind poet O’Mahon in a quiet high voice that stills them all:

Fubún on the gray foreign gun,

Fubún on the golden chain;

Fubún on the court that talks English,

Fubún on the denial of Mary’s son.

Hugh listens, turning from one speaker to the other, frightened by the poet’s potent curse. He feels the attention of the O’Neills on him.

* * *

“In Ireland there are five kingdoms,” O’Mahon the poet said. “One in each of the five directions. There was a time when each of the kingdoms had her king, and a court, and a castle-seat with lime-washed towers; battlements of spears, and armies young and laughing.”

“There was a High King then too,” said Hugh, seated at O’Mahon’s feet in the grass, still green at Hallowtide. From the hill where they sat the Great Lake could just be seen, turning from silver to gold as the light went. The roving herds of cattle—Ulster’s wealth—moved over the folded land. All this is O’Neill territory, and always forever has been.

“There was indeed once a High King,” O’Mahon said.

“And will be again.”

The wind stirred the poet’s white hair. O’Mahon could not see Hugh, his cousin, but—he said—he could see the wind. “Now cousin,” he said. “See how well the world is made. Each kingdom of Ireland has its own renown: Connaught in the west for learning and for magic, the writing of books and annals, and the dwelling-places of saints. In the north, Ulster”—he swept his hand over lands he couldn’t see—“for courage, battles, and warriors. Leinster in the east for hospitality, for open doors and feasting, cauldrons never empty. Munster in the south for labor, for kerns and ploughmen, weaving and droving, birth and death.”

Hugh, looking over the long view, the winding of the river where clouds were gathered now, asked: “Which is the greatest?”

“Which,” O’Mahon said, pretending to ponder this. “Which do you think?”

“Ulster,” said Hugh O’Neill of Ulster. “Because of the warriors. Cuchulain was of Ulster, who beat them all.”

“Ah.”

“Wisdom and magic are good,” Hugh conceded. “Hosting is good. But warriors can beat them.”

O’Mahon nodded to no one. “The greatest kingdom,” he said, “is Munster.”

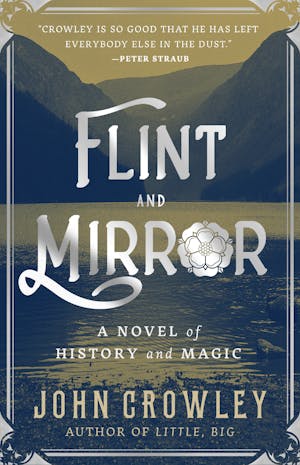

Copyright © 2022 by John Crowley