CHAPTER 1Letter to the Future

Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland, 1791

BENJAMIN BANNEKER TIPPED back his chair and rubbed his eyes. It had been a four-candle night. When his final candlestick guttered out, he set his quill in the inkpot. He stood up, but his feet had fallen asleep in the long hours of sitting, so he hobbled a bit on them, rocking from his toes to his heels.

Benjamin stepped onto the porch and looked out over his land. The world was awakening, coming on in birdsong and rooster calls, in sunlight burning off the mist over the orchard. He had spent many nights lying in those fields, looking up through a telescope, jotting down notes. He had tracked the stars and planets as they passed the meridian, and had made the equations necessary to predict the precise times of an eclipse, as well as equinoxes and solstices, sunrises and sunsets. He had drawn out the phases of the moon and had projected all the major astronomical events for the coming year. His almanac for 1792 was finally complete.

Benjamin took a quick walk around the orchard, clearing his mind. He twisted the stiffness out of his back and stretched his arms up toward the sun. He knew that being in relationship with the sun and the stars had always been a matter of survival. His people in Africa had followed the stars in their sky maps, and now he had the mathematical skills to track celestial events on paper, in an almanac that would be of practical use. The almanac would help farmers plan the best time to plant their crops, and fishermen to safely cast out into the tides.

Benjamin checked his beehives and plucked some chives from the garden. Then he walked to the chicken coop and pulled two warm eggs from a nest. He stood at his kitchen hearth, stirring the eggs and chives into a skillet, preparing his breakfast while preparing his thoughts. He knew what he had to do next.

* * *

BENJAMIN CLEANED THE nib of his quill and smoothed out a fresh piece of paper. As he addressed the letter to Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State, he felt his hand tremble and clench a bit. His practiced, elegant penmanship was boring down on the page. He began cordially, acknowledging the fact that Jefferson had probably never received a letter from a Black man:

Sir,

I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion, a liberty which Seemed to me Scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished, and dignifyed station in which you Stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.

Benjamin reminded Jefferson that he was a free man, endowed with the same liberties as Jefferson himself. Then he contrasted his own situation with that of most African Americans, who were still enslaved.

By the third page of the letter, Benjamin was directly addressing the founders’ hypocrisy. He reminded Jefferson of the Revolution and began quoting his most famous written work—the Declaration of Independence—back to him, writing:

This, Sir, was a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a State of Slavery, and that you publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remembered in all Succeeding ages. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

… but Sir, how pitiable it is to reflect, that although you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of those rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the Same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you profoundly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.

Benjamin Banneker sat back in his chair. He was surprised by his own clarity, by the way the words had flowed out on a rhythm of truth. He concluded the letter to Jefferson by admitting that he had not set out to write such a long message, but his “sympathy and affection” for his enslaved brethren had caused the letter’s “enlargement.”

Benjamin put the almanac and letter into an envelope, addressed it to Thomas Jefferson, and walked the three miles to the Ellicott & Co. Store so it could be posted. As he left the package and walked back over the stone bridge, along the wooded paths beside the Patapsco River, he took long, deep breaths of the fresh air. He felt expansive, almost elated. He felt that one of the central purposes of his life had been completed.

CHAPTER 2Denial in the Bloodline

Asheville, North Carolina, October 2016

TO CONSIDER YOURSELF part of a family, or a nation, is to live inside a story of what that means. We didn’t know it yet, but ours was shifting, exposing fault lines and omissions that had been in it all along, revealing itself to be just that—a story. In need of revision.

My extended family was gathered in Asheville, North Carolina, for my cousin Laurel’s wedding. It was the night before the reception, and we were out on my aunt Janice’s deck, eating chili, drinking beer and lemonade. The weather was mild, and we were enjoying one of the last evenings of the year when we could wear short-sleeved shirts and sundresses. It was the last month that I would believe in a shared national narrative, the last week that I would assume I lived in ordinary times.

My 102-year-old grandmother sat in the best chair in the living room, with my cousin on the floor beside her, holding her hand. My grandmother had always said that she would live to be 100, and somehow, she’d made it—through her own stubborn determination and the devotion of her daughter who cared for her at home. My grandmother’s great-grandchild, Haley, had also brought her children to the celebration, and as Haley bounced nine-month-old Teagan on her lap, I observed five generations of women together.

I was watching them through the window, so I don’t know what they were talking about, but it probably wasn’t the conversation we were having out on the deck. Earlier that day, the Access Hollywood tape had leaked that showed Donald Trump bragging about sexually assaulting women. We were debating whether he would be forced to drop out of the race by other Republicans, who tended to denounce such behavior patriarchally, as protective fathers and husbands. Tension had been rising all election season. It seemed that the entire country was balanced on a fault line between Republicans and Democrats, blue states and red states, one way of understanding America and another.

“I think we are just going to have two countries,” my nine-year-old daughter had declared. “I think we’ll have the red states and the blue states, and we’ll decide that we don’t want to be the same country anymore.”

I told her that the nation had experienced similar rifts before. The years and months leading up to the Civil War, and the war itself, must have felt like this. The years leading up to the Revolution must have felt like this too. Even the years following the Revolution were tumultuous, as many citizens wondered if it had been right to break with England. We tend to talk about history as if it was easier back then to be courageous, and as if American success had been preordained. But it was always a long shot, and our success—that is, any functional national unity—has always been a patchwork job. The United States was the most ideological governmental experiment in history, but huge swaths of the country were excluded from its legalized liberties because they were African American, Native American, non-white, or female. Now, as we found ourselves at another turning point in history, the question seemed to be whether we would finally confront our nation’s foundational hypocrisies or stay in denial about these historical and ongoing inequities. We were at a narrative divide, with the people of the country occupying at least two drastically different stories of what America means.

Even my own field of creative writing was being roiled and split around issues of cultural appropriation, literary ethics, and representation. I began my career creating workshops for teens, all of whom were students of color, through the Urban League of Portland, Oregon, and the City of Chicago. After a decade of learning from these students and working to decolonize education, I began teaching at the highly privileged Northwestern University, where I diversified reading lists and implemented social justice training as part of the creative writing curriculum. I had been waiting my entire adult life for the kinds of conversations that were taking place, but I was disturbed by the vitriolic blaming that seemed to be driving the discourse. Shame creates shutdown rather than openness to transformation, and as an educator, I had to believe in transformation. The conversations of our time had become so polarizing that I had begun to worry that my wisest, most sensitive students—of any ethnicity or background—would become too afraid of backlash to even take the risk of writing.

My creative writing students and I had spent the fall quarter asking the question of who gets to tell which stories. Some of the most vocal students said that we should only write about characters who look like ourselves, who occupy the same basic socioeconomic and racial categories as we do. Some said that we should always ask permission of who we tell a story about, and that we should be prepared to drop our project if the answer from a marginalized group is “no.” One student—a young Black woman and Black Lives Matter activist—pointed out that we were having this conversation as if the playing field was level, and it is not. She argued that the issue is not about storytelling as much as it is about power and access. Many said that we were obligated both to write our own stories and to widen the field of literature for writers of color or any writers who had been marginalized in the past.

I was moved by their emotional intelligence, and I agreed with their insistence that systems of power needed to diversify. I also agreed that representation is important, that no one can imagine the stories of a group better than a member of that group itself. We talked about the fact that freedom of speech and expression have never been applied equally in our culture, and oftentimes those who call for freedom are calling for their own immunity, or even the right to engage in harmful speech.

But I still wanted the students to consider what would be lost to us—as writers and as humans—if we really decided that it was impossible to imagine what it is like to be a person from a different background. Narrowing our subject matter that dramatically would collapse the work of learning in writing, the expansive discovery that happens when we research and imagine something beyond our personal experience. It would also shut down our relationship to unknowing, which is probably the most fruitful relationship a creative writer can have. Creative writers do not write simply to advance an argument, after all, but to discover what they do not yet know, and the best writers and the best writing change right on the page. We were living in an age of opinion, but most literature is not an argument for what should be, as much as it is a depiction of the tangled, poignant mix of what is.

We were trying to make space for one another’s truths in that classroom, and it was frightening. It felt almost impossible to talk about these issues without saying something problematic. Afterward, one of my students from Singapore wrote, “My voice was shaking, my hands were sweating, but this was important. I thought, this must be what citizenship feels like.”

Ironically, the students who were most militantly against cultural appropriation were white, progressive, newly sensitized to the Black Lives Matter movement, and to issues of equality as they related to elite education and the elite worlds of publication—worlds that they were set to inherit. These were the students most likely to insist that we should write only about ourselves or characters in our own demographics. As young adults, they had not yet exhausted their interest in themselves, and they did not trust any impulse to tell stories that lay outside of their experience. We all lived within the machine of capitalism, after all, and within capitalism, encounters with other cultures usually lead to absorption and exploitation.

Many of my ethnically diverse students had more complicated responses that reflected their own complex identities, and sometimes stemmed from a feeling of responsibility to their communities. “As an Asian American woman, I can feel pigeonholed that I just have to write about being Asian, but I grew up at boarding schools in the U.S. and have had a ‘white,’ privileged education,” one said. “Can I write about that?”

“As a mixed-race person,” one young man said, “I would think that I would feel invited to write about myself and my ancestry right now. But I feel more afraid and shut down than ever. My grandfather crossed the border illegally and spent his life as a migrant worker in the fields, but I have never worked in the fields, so how can I write about him? Am I allowed, and do I have the imagination necessary, to write about my own grandfather?”

One student said that maybe the future of writing would be more collaborative, and we agreed that our notions of authorship needed to evolve, to catch up to the collective change-making happening through activism and social media. We discussed ways that stories could adhere less to the myth of the individual, seeing that individualism is itself a product of the dominant culture that most of us wanted to challenge. After all, every individual is a result of families, communities, societies, both personal and structural connections.

“How can we undertake ethical collaborations in our writing?” I’d prodded them. “And in addition to literal forms of collaboration, how can we think about collaboration more broadly? Who is to say that if J.D. sat alone in his room for two years, writing about his grandfather working in the fields, that he was not also engaging in some form of collaboration with his ancestor, some co-creation between the self and other that happens in the space of the imagination?”

The students just stared at me then. I was getting a little too woo-woo for them. They distrusted any cloudy thinking in an age when truth itself was under attack. Although they were all creative writing majors, ostensibly apprenticing in the arts of the imagination, our politicized time had attuned them more to activism than to other forms of artmaking.

“There is a mystery to the imagination,” I’d continued. “We can feel intimately connected to others’ stories. We can feel like we almost remember things that we have not actually lived.”

* * *

I WAS OUT on my aunt’s deck, telling my cousin Nathan about these conversations in my classes. He was squarely in the camp of “writers should only write about their own demographics” and said that we all need to read more books by people of color. Then he said, “But these questions become more interesting when you take into account most Americans’ mixtures of ancestry, including our own non-white ancestry.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

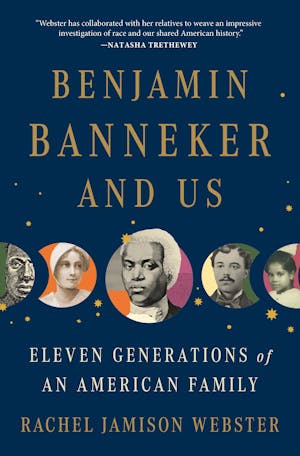

“Didn’t Melissa tell you? She was researching the Webster genealogy this summer and found out that we are related to Benjamin Banneker, the colonial African American clockmaker and almanac writer. You know, the guy who helped to survey Washington, D.C.?”

I went blank. I was embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know. Any of it.

* * *

LATER THAT WEEKEND, I found a moment to talk to our cousin Melissa alone, and she confirmed what Nathan had told me. One of our great-aunts and a cousin had looked into our Webster genealogy over the years in an attempt to determine if we were related to Noah Webster, who had compiled the first U.S. dictionary, or Daniel Webster, who was a congressman in the nineteenth century. But we were descended from neither of them.

“Because all of that had already been done,” Melissa said, “I decided to look back through Grandpa’s mother’s line, where Grandpa’s sisters had not seemed interested in researching. In the census records, all of these people had an M. next to their names.”

For “mulatto,” she realized. This line went back through our grandfather’s mother and her father, through the generations to Jemima, Benjamin Banneker’s sister, and their parents, Mary and Robert, before ending with Molly Welsh and Bana’ka—the British woman and African man who were our first American ancestors.

After the wedding, I asked my parents if they knew about this, and they confirmed that, yes, they had heard this story but had forgotten to tell me. For Christmas the year before, my brother and I had bought them DNA tests through Ancestry.com. I asked my brother to email me the results of our dad’s DNA test, and there it was. On my dad’s genealogical map, England, Ireland, and France were filled with bright colors, denoting most of his origins, and the other countries that were filled in were Senegal and Guinea.

Somewhere along the way, my family had swallowed a silence that I hadn’t known we’d had.

Copyright © 2023 by Rachel Jamison Webster