1.

SET AN EXAMPLE

The Story of 24

“People judge you all kinds of ways. Let them say what they want. Be your own judge. Trust your heart.”

—Willie Mays

WILLIE MAYS WAS twenty-six years old and the most exciting player in baseball when the Giants moved from New York to their new home in 1958. San Francisco, however, was Joe DiMaggio’s town.

DiMaggio was a native son born to Sicilian immigrants who settled in the fishing community of Martinez before relocating across the bay to San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood, where young Joe and his brothers played ball on the sandlots.

After emerging as a local legend with the San Francisco Seals of the old Pacific Coast League, especially amid his 61-game hit streak as an eighteen-year-old in 1933, DiMaggio became a New York Yankee, the heir to Babe Ruth, and hit in 56 straight games and won nine World Series. He played through 1951, the year Mays broke into the big leagues.

After the Giants arrived in San Francisco, DiMaggio’s celebrity didn’t vanish. Some locals welcomed the team but were unconvinced of Mays, who had earned his claim to fame in New York. That Mays played DiMaggio’s position in DiMaggio’s ballpark in DiMaggio’s town made it difficult to be accepted at first.

They didn’t know me. At that time, I felt they still wanted Joe to shine. He was from San Francisco and went on to play for the Yankees. They thought nobody else could play center field except him. That’s what I got out of it. I think sometimes they wanted somebody else to be the leader of the ballclub.

Mays was learning what Mickey Mantle had gone through in New York. Following the great DiMaggio is no easy task. But unlike Mantle, who was DiMaggio’s immediate successor on the Yankees, Mays appeared in San Francisco twenty-three years after DiMaggio last played for the Seals.

Still, a full generation later, Mays took the Seals Stadium field and wasn’t fully appreciated. As wacky as it now seems, there were boos. Not always. Not rampant. Not consistent. But boos nonetheless. There were media criticisms. Not because he wasn’t fantastic. Not because he wasn’t the best player on the field. But because he wasn’t DiMaggio, because he was the face of the franchise that displaced the beloved Seals, because there was hesitation to immediately adopt a New York star, because (at least for some) of his skin color.

And also because of Orlando Cepeda and other young players emerging from a rich and diverse minor-league system.

“Well, it’s because they billed him so high,” said Cepeda, who was named the National League’s top rookie with the 1958 Giants. “San Francisco had been a Triple-A town, not a big-league town. They had never seen Willie play every day. But when they saw Willie play every day and saw him do the things he could do on the field, things changed. Because the things Willie did on the field in those days, nobody else did. Still today, I don’t see players doing what Willie did.”

Cepeda was the toast of San Francisco, having never played with the Giants in New York. He was twenty years old when breaking in, just like Willie. It was a strange dynamic, not everyone quick to embrace Mays, but most cynics eventually came to their senses and welcomed his one-of-a-kind talent. Cynics who didn’t were ignored as contrarians who simply wanted attention.

Or, worse.

Race was a factor, of course. Before his first season in San Francisco, Mays and his wife tried to buy a house in an upscale San Francisco neighborhood and were denied because they were African American. After a storm of publicity and intervention from the mayor, they eventually bought the house, but a year and a half later, someone threw a bottle through the front window with a hate note inside.

Apparently, it was okay for the great Mays to tirelessly represent the city and region and delight thousands of fans every night so long as he didn’t live in certain people’s neighborhoods.

“That was 1958 when he came to San Francisco, and 1958 was 1958. We’re past some things. We’re not past everything,” said Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, who grew up in Oakland and whose father took him to Giants games in those early years. “There were some writers who were critical and didn’t want to give Mays his due because he was from New York. I didn’t see DiMaggio play, but he was the golden boy of San Francisco. You’ve got to remember that. For a lot of people, Mays was the guy who was taking his spot.”

Mays didn’t see it that way. He had nothing against DiMaggio. In fact, as a kid growing up in Alabama, he idolized DiMaggio and wanted to emulate his all-around game.

I looked up to Stan Musial, Ted Williams, and Joe DiMaggio. I read about them in the papers. They were on the front page all the time, all over the headlines, Stan the Man, the Splendid Splinter, Joltin’ Joe. Great outfielders, great ballplayers. This was before Jackie Robinson. I liked Joe and wanted to be like Joe, a guy who could do everything on a baseball field.

When I came out west in ’58, they always talked about Joe being the San Francisco guy. There was no other center fielder except Joe. I didn’t say anything or let it bother me. I just moved on and played. They didn’t know that Joe was my guy, too. In the ’51 World Series, he hit a home run, and I’m out there in center field clapping.

I don’t remember doing too many things wrong, but what am I doing out there clapping for this man? I had to catch myself. I always wondered why nobody took that picture.

Over time, most if not all of San Francisco warmed to Mays, and why not? He no longer was in a New York uniform or playing home games in the Polo Grounds. He was in his prime and fully dedicated to San Francisco, where he lived year-round and was active in the community. He was inspiring a game, a nation, and many a generation and being called the greatest all-around player in the history of baseball, an American icon, a treasure, a hero.

What’s not to love? Beyond the on-field athletic brilliance—no one was more gifted in so many areas or played with such artistic swagger—Mays, a major-leaguer just four years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers, was known for his personal strength and integrity. While sports in general and baseball in particular have been plagued by scandals over the years, Mays’ story is honorably refreshing. He gives his life to charitable causes, especially involving children and public safety, as a philanthropist through his Say Hey Foundation and other avenues, a calling that dates to his playing days—in 1971, he was the first recipient of what became known as the Roberto Clemente Award, a prestigious philanthropic honor named after the great ballplayer who died in a plane crash trying to aid victims of a Nicaragua earthquake.

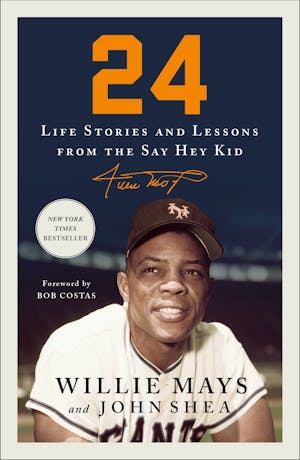

Willie Mays’ number 24 was retired by the Giants, whose ballpark is at 24 Willie Mays Plaza. (San Francisco Giants)

“I didn’t dream about being president. I dreamed about being Willie Mays until I realized I couldn’t hit. The presidency thing was the farthest thing from my mind. Being a ballplayer wasn’t,” said former president George W. Bush, who grew up in a baseball family and owned the Texas Rangers before becoming governor of Texas and then president. “I was an aspiring young kid. I collected baseball cards. I was just a baseball guy. I loved the game. Still do. When friends of mine and I bought the Rangers, it was like living the dream to be involved with Major League Baseball at that level. So Willie in many ways cemented my love of baseball. He was aspirational for me. I didn’t know much about him other than the fact he was a great baseball player. And to think he came out of Alabama and battled his way through the segregation era and went into the Army, he’s a man of remarkable talents but also remarkable drive.”

Bush was born in the summer of 1946, as was former president Bill Clinton, the first two baby-boomer presidents, both with an early love and appreciation for baseball and both captivated by Mays, an immensely popular celebrity among the first generation that emerged after World War II. The country turned its attention to leisurely activities just as the Golden Age of baseball arrived, and Mays was at the forefront not just as the game’s premier overall player but the most entertaining.

“I loved watching Stan Musial and the Cardinals, and I liked the Brooklyn Dodgers because of Jackie Robinson. They had a great roster in the ’50s,” said Clinton, who grew up in Arkansas listening to Harry Caray calling Cardinals games, “but my favorite player from the beginning was Willie Mays. He played with so much joy, and he had so many skills. I just liked him. He could do everything well. The Polo Grounds was a tough place to play baseball because it was so deep to center field, but the way he ran around out there was something to behold.”

Mays’ cumulative accomplishments are unparalleled—660 home runs, 3,283 hits, 338 stolen bases, 12 straight Gold Glove awards, 24 All-Star Game appearances—as well as his five-tool proficiency: hitting for average and power, fielding, throwing, and baserunning. Perhaps more than any player in history, a case can be made that any one of Mays’ tools is as elite as the next. He runs as well as he hits as well as he defends. There’s no clear answer as to which is his best tool. Or worst, for that matter.

Snapshot moments include the basket catch that he perfected in the Army, the cap flying off his head as he raced from first to third, the World Series catch shown for eternity in black-and-white, the four-home-run day at Hank Aaron’s park in Milwaukee, the 16th-inning homer to beat Warren Spahn 1–0, and the eighth-inning homer in the 1962 finale that led to a playoff with the Dodgers.

Generations have admired Mays’ ability and determination along with his charm and flair. His honorable life has stood the test of time. Mays’ fitting nickname—the Say Hey Kid—depicts a youthful exuberance that never went away. In his early days with the Giants, he didn’t know everyone’s name, so he’d just say “hey,” usually in his distinctive and energetic high-pitched voice that lit up a room or dugout, and a sportswriter named Barney Kremenko was credited with naming him the Say Hey Kid. These days, Mays attends nearly every Giants home game, was a constant during the team’s three World Series championship runs in 2010, 2012, and 2014, and engages in lively clubhouse banter as if he were still kicking it in his twenties and thirties.

“Willie’s the greatest all-around player of all time,” said Dodgers manager Dave Roberts, the majors’ only African-American manager in 2019. “You listen to his stories, you learn so much. The details, the color, the humor. Nobody tells stories like Willie. If anyone has a right to walk around with a big head, it’s Willie Mays. But he’s so humble, so funny. He’s one of the guys. He has a great love for the game. The ballpark is his second home, maybe his first home, and when he tells his stories, he inspires us all.”

And from Hall of Fame outfielder Dave Winfield: “Watch his highlights. Always hustling. Look at his body. Dude was chiseled. He could fly and catch the ball, and he did it with a smile. Listen to the stories he tells. Always enjoying what he’s doing, always with a sense of humor. If these young players were intelligent and bright and cared about the game, they’d learn from Willie. They should all go back and watch his highlights and listen to what he has to say.”

Mays was listed at 5-foot-10 and anywhere between 170 and 180 pounds, though he swears 5-foot-11 is more accurate. Either way, it’s not by any means the standard physical stature of a slugger. Ruth and DiMaggio were 6-foot-2. While Mickey Mantle, Reggie Jackson, and Harmon Killebrew were close to Mays in height, newer-generation hitters Ken Griffey, Jr., Barry Bonds, and Alex Rodriguez all tower over Mays. Mel Ott, at 5-foot-9, is the only member of the 500-homers club shorter than Mays.

I have been blessed to be in the game. A lot of my love for baseball comes from my dad. We’d sit and talk baseball all day. I played football and basketball. Baseball was my third sport. You don’t have to be a big guy to play baseball. You can be regular size as long as you can hit and throw and run and all that kind of stuff.

Mays’ retired uniform number—24—is one of the most recognized and iconic in sports. He has a nine-foot bronzed statue in his likeness at 24 Willie Mays Plaza, home of the Giants’ ballpark along the San Francisco Bay, where 24 palm trees surround the statue and the right-field brick wall stands roughly 24 feet high. On his eighty-fifth birthday, Willie was honored when a San Francisco cable car was dedicated to him. Car 24.

Willie Mays played twenty-two seasons in the big leagues and batted .302 with 660 home runs for the New York Giants, San Francisco Giants, and New York Mets. (San Francisco Giants)

The Giants retired the number long ago, but others have worn it in Mays’ honor. Rickey Henderson, for example. The all-time stolen base king played for nine teams over his 25-year career and wore 24 on six of them, including his hometown Oakland A’s. No one ever again will wear the number with either Bay Area team. Like the Giants, the A’s retired 24.

“I take a lot of pride in that number,” Henderson said. “I met Willie when I was a young man, at a kids’ clinic. I was probably thirteen. You looked up to him and wanted to be like him. You better be good to wear that number. You don’t just put that number on and not represent.”

Tony Pérez grew up in Cuba and, through the influence of his father, José Manuel, idolized Robinson and Mays. Pérez wore 24 as the run-producing first baseman on Cincinnati’s mighty Big Red Machine of the 1970s.

“When I got to the big leagues, they gave me 24, and I said, ‘Wow, I’ve got Willie Mays’ number,’” Pérez said. “I never forgot that moment. He was the most complete player in the game. He could do it all. When I played against Willie, I felt like a fan. Maybe some players were faster, but I’ve never seen anybody run the bases like Willie. When he hit the ball in the gap, I watched him go by me at first base, and when he rounded second, he wasn’t even watching the coach. He was watching the ball and outfielder. He never missed a step. I couldn’t believe it.”

Among the Hall of Famers who wore 24: Mays, Henderson, Pérez, managers Walt Alston and Whitey Herzog, and Griffey, who wore it for Rickey, who wore it for Willie. That was Barry Bonds’ number in Pittsburgh before he signed in San Francisco, where he wore 25, the same number of his dad, Bobby Bonds. Talk of the younger Bonds getting 24 with the Giants—because of Mays, his godfather—quickly got nixed.

It’s not just a baseball thing. Basketball Hall of Famer Rick Barry, who led the Golden State Warriors to the 1974–75 NBA championship, grew up in New Jersey, where his father, Richard, taught his son the basket catch, the unique glove-at-the-waist method of catching fly balls that Mays popularized. Barry watched Mays plenty of times at the Polo Grounds.

“That’s my boyhood hero,” Barry said. “When I started playing sports, I wanted 24. I wore it all the way until I got to the Houston Rockets. I couldn’t wear it there because Moses Malone had it. So I wore 2 at home and 4 on the road. I just told them that’s what I want to do. Nobody said anything. I did it for two years.”

One day, Barry cut school to see Mays at the Polo Grounds. “After the game was over, I jumped the left-field fence, dropped on the field, and sprinted to catch Willie before he went up the stairs to the clubhouse,” Barry said. “I shook his hand, ran back, and got on the bus to head home. My mom and dad were both working, and my brother said, ‘How was the game today?’ ‘I said, ‘What are you talking about? I was at school.’ He said, ‘No, you weren’t, you were at the game. I saw you on TV. The cameraman was on this kid who jumped over the wall and sprinted out to Willie Mays. It was you.’ I said, ‘Oh, my God, don’t tell mom or dad, please.’”

Like the basket catch, Barry’s free-throw style was unconventional. One of the all-time great free-throw shooters, he shot underhanded. Most everyone else shoots with the arms raised. Just like most everyone else catches fly balls with the arms raised.

“The similarities are there,” Barry said. “I’ve become friends with my boyhood hero, and we both did things that have gone out like the dinosaur even though we were successful doing it.”

Mays briefly wore 14 when getting called up in 1951 before settling on 24, which had been worn by an outfielder named Jack Maguire, whose claim to fame was giving Lawrence Peter Berra his nickname: Yogi. Maguire played 16 games that season for the Giants and was claimed by the Pirates about the time Mays arrived.

It was the number the Giants gave me. A lot of our outfielders wore higher numbers back then, mostly in the 20s. Monte Irvin. Don Mueller. Bobby Thomson, who was the center fielder before I came along. I had worn other numbers before coming up and didn’t think a lot of it, but I enjoyed wearing 24, and a lot of guys over the years have liked wearing it. It’s nice to know that.

Mays continued putting on 24 after his spring 1972 trade to the New York Mets, where owner Joan Payson had a great fondness and appreciation for the center fielder, dating to her minority ownership of the New York Giants. Mays recalls Payson saying no Met would wear 24 again. She died in 1975 and never officially retired the number.

For the most part, the Mets have granted Payson’s wish. There was a blunder in 1990 when Kelvin Torve, a late-season call-up, was given 24, a mistake that led to a backlash and quickly got fixed—Torve was given 39. Rickey Henderson wore 24 as a Met in 1999 and part of 2000 but only after checking with Mays.

“I had to call him and get his permission,” Henderson said. “He said I could wear the number. That was a blessing to me.”

Mays had imagined the Mets keeping his number out of circulation but admires Henderson as a person and player, including Rickey’s combination of power and speed. That was supposed to be the lone exception, but the Mets, amid a front-office overhaul, gave 24 to Robinson Cano in 2019 after acquiring the infielder in a trade with Seattle. Cano had worn 24 with the Yankees but couldn’t wear it in Seattle because it was retired for Griffey.

“My dad told me all the things Jackie Robinson went through, the barriers he broke for future generations,” said Cano, who was named after Robinson and likes 24 because it’s the reverse of Jackie’s 42, which is retired throughout baseball. “But every time you think about number 24, you go back and think about Willie Mays. He was the one who gave real value to the number. I mean, he’s a legend. There is no other word for him. That is what 24 represents for me.”

While it would seem unusual to retire someone’s number after just two seasons with a team, it’s exactly what happened with another celebrated player, Hank Aaron. Like Mays, Aaron played for a team (Milwaukee Braves) that relocated to another city (Atlanta) and was traded late in his career to a different franchise in his original city (Milwaukee Brewers). Naturally, the Braves retired Aaron’s number, 44, but so did the Brewers, who used him as a designated hitter in 1975 and 1976.

Regardless, Mays has moved on. He’s happy the Mets retired the number of one of his favorite teammates, Tom Seaver, and appreciates that 24 is such an important part of the Giants’ and the city of San Francisco’s fabric.

“A lot of guys wanted 24, and no doubt some did 24 very proud,” said Morgan, who was a teammate of Pérez and Griffey’s dad, Ken Griffey, Sr., in Cincinnati. “Willie Mays is the only 24 I recognize, to be honest with you.”

Mays’ legacy goes well beyond what number he wore. Or what numbers he put up. He has touched countless lives, and he has been touched by a long list of people who have helped shape his own life. His father, Willie Howard Mays, Sr. His Negro League manager, Piper Davis. His New York Giants teammate, Monte Irvin. His first big-league manager, Leo Durocher. And others who helped prepare and inspire him after he retired as a player, including the younger generation, whether it’s current players or America’s youth.

And, as always, the fans.

I was always aware that you play baseball for people who paid money to come see you play. You play for those people. You want to make them smile, have a good time. I would make a hard play look easy and an easy play look hard. Sometimes I’d hesitate, count to three, then I’d get there just in time to make the play. You’d hear the crowd. Sometimes you had to do that in order for people to come back the next day.

They often did.

“Willie Mays was, in my view, the greatest all-around baseball player in the history of the game,” said John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, who grew up in the Bronx a Dodger fan. “What could he not do? Not the greatest hitter, or fielder, or thrower, or base runner … but the greatest combination of all those skills.”

Copyright © 2020 by Willie Mays and John Shea