INTRODUCTION

I like the surprise of the curtain going up, revealing what’s behind it.

—John Schlesinger

John Schlesinger was looking forward to a triumphant entry on his first visit to Hollywood. Darling, the British director’s third professional feature film, had been a surprise hit on both sides of the Atlantic, winning three Academy Awards and introducing international audiences to twenty-five-year-old Julie Christie, whose fresh looks and exuberant energy embodied the naughty spirit of Swinging London. She played Diana Scott, a thoughtless and predatory supermodel who broke up marriages, yawned her way through orgies, and generally set new records for narcissism and duplicity, yet radiated an irresistible charm and vulnerability that made you feel sorry for her even as you cheered her downfall. It was only Christie’s second major film, yet with Schlesinger’s careful direction, she gave such an adept and nuanced performance that she won the Oscar for Best Actress.

The year was 1966 and Hollywood loved new talent, especially when it came with a British accent. The moviemaking capital of the world had recently embraced Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney, Sean Connery, Julie Andrews, and Michael Caine, and now it loved Julie Christie and the thoughtful filmmaker who had recognized and captured on film her seductive charisma.

Suddenly, after a decade-long apprenticeship making short, spirited documentaries for BBC Television and low-budget black-and-white feature films, John Schlesinger was the hot new thing, a movie director of wit, irony, and substance. Everyone wanted to meet him, and powerful people were pushing substantial projects toward him, including Funny Girl and Fiddler on the Roof, both of which he turned down. Best of all, studio heads were asking, “What do you want to do next, John?” And when John said what he wanted to do next was a big-budget adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Victorian novel Far from the Madding Crowd, starring Christie, Alan Bates, Peter Finch, and Terence Stamp—among the cream of British acting talent—MGM said yes.

He spent six months slogging with cast and crew through the quaint market towns and ancient, picturesque fields of rural Dorset and Wiltshire in southwest England. When the film was finished, the studio flew three hundred journalists to London, housed them at the Savoy, and treated them to a week of free food, royal welcomes to Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace, boat rides and bus trips through Thomas Hardy country, and a star-studded preview at the Marble Arch Odeon. Movie premieres were planned for New York and Los Angeles, with another one squeezed between them at the last minute for Washington, D.C. Success was a foregone conclusion.

Then the reviews started arriving. Far from the Madding Crowd bombed. Despite its lush visual beauty and fine acting, the film was too modern to feel authentic, yet too traditional to feel youthful, and Christie’s curiously underwritten character careened from headstrong, independent woman to swooning fool for love, a modern material girl trapped in a nineteenth-century soap opera. The New York Times’ chief film critic, Bosley Crowther, usually a sucker for sincere classical epics, mournfully branded it “sluggish, indecisive, and banal.”

John Schlesinger, who thought he was coming to America for a coronation, instead found a wake.

At the New York premiere, he could sense members of the audience slipping into a coma. There was utter silence at the end. “It was frightfully slow,” he would later admit. “We were too much in awe of Thomas Hardy.”

A lavish premiere party had been planned for after the screening at the Grand Ballroom of the Plaza Hotel. When John walked in, he noticed there were only three full tables. The handful of intrepid guests applauded wanly. “It was an absolute disaster,” he recalled. Even his parents slipped out early.

By the time he awoke the next morning, the Washington premiere had been canceled. Instead, he flew directly to the West Coast, escorted by the head of publicity for MGM. The man asked gingerly what John was planning for the future, then offered a piece of advice: “Be very careful what you do next—you can’t afford to make something which is really not right for you.”

Despite his sudden belly flop as a big-time director, John Schlesinger had no intention of doing anything other than what he thought was right for him. And what was right for him, he had decided, was to make a film out of a novel that was so bleak, troubling, and sexually raw that no ordinary film studio would go near it.

* * *

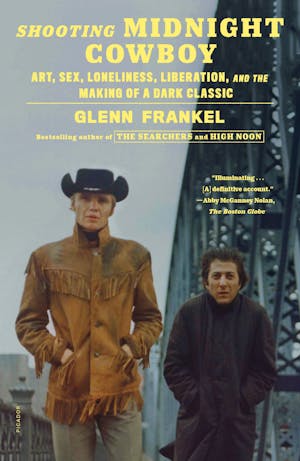

Midnight Cowboy, written by James Leo Herlihy and published in 1965, tells the story of Joe Buck, a handsome but not overly bright dishwasher from Texas who buys himself a cowboy outfit and hops a bus to New York City to seek his fortune by becoming a male hustler selling sexual favors to frustrated older women. Joe’s business plan fails miserably and he winds up squatting in a shabby and deserted apartment building with Ratso Rizzo, a disabled, tubercular con man and petty thief. Ratso becomes Joe’s host, pimp, adviser, and, ultimately, his friend. Joe ends up turning tricks with men in Times Square, and savagely beats and robs one older customer to buy bus tickets to Florida for himself and his desperately sick friend, who wets his pants and dies just before the bus arrives in Miami. The book contains scenes of heterosexual and homosexual intercourse, sadomasochism, fellatio, gang rape, prostitution, and illegal drug use.

Trapped inside the straitjacket of Hollywood’s old Production Code system of censorship—under which even a husband and wife couldn’t be seen sleeping together in the same bed, and a toilet could never be shown, let alone flushed—Midnight Cowboy could not have been made just a few years earlier. But by 1968, the year after the disastrous release of Far from the Madding Crowd, the motion picture industry was in deep trouble. Ticket sales had been steadily falling for more than two decades, and most of the studios were sliding toward insolvency. The genres that had sustained Hollywood during its long golden age—westerns, musicals, romantic comedies, biblical and historical epics—had grown stale and predictable, and many of the highly paid stars and filmmakers who worked in them had lost the magical power to attract increasingly younger audiences. In a time of political upheaval and changing social mores, Hollywood seemed less relevant than ever.

The studio heads, cognizant of their economic precariousness, had recently scrapped the old code and replaced it with a ratings system designed to allow for more adult stories, themes, and language. Not everyone embraced the new system; church groups, parental activists, and local politicians in small-town America—the backbone of the moviegoing public for generations—feared a loosening of moral standards and a threat to the well-being of children.

Just as there were deep divisions and uncertainty inside the film industry over box office receipts and freedom of expression, so the country was torn by political unrest at home, a protracted and self-destructive war in Vietnam, the murders of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, the betrayal of the hard-won victories of the civil rights movement in school desegregation, voting rights, and social justice, and the demands for equality and recognition by the women’s liberation and gay rights movements. Richard Nixon, a conservative Republican, captured the White House in November 1968 in a narrow electoral victory over liberal Democrat Hubert Humphrey, while a third-party insurgency led by former Alabama governor George Wallace helped awaken and inflame the populist demands and racial fears of white working-class voters. The election capped a pivotal year when, according to social historian Charles Kaiser, “all of a nation’s impulses toward violence, idealism, diversity, and disorder peaked to produce the greatest possible hope—and the worst imaginable despair.”

The birthplace and battleground for many of these conflicts was New York City. Emerging from World War II as the world’s greatest metropolis, New York by the late 1960s was on a downward path to seemingly terminal decline, fueled by economic hardship, rising crime, political violence, and government repression and ineptitude. Yet it was also the incubation chamber for daring and innovative experiments in popular culture and sexual expression, including film, art, literature, theater, and music. Thousands of young people still poured into the city each year, seeking not just a job or an education but a sense of identity and adventure. New York was never a refuge—the city’s embrace was far too noisy, edgy, chaotic, and dangerous for comfort or reassurance. But it was exhilarating. “The city arouses us with the same forces by which it defeats us,” wrote literary critic Alfred Kazin, who spent a lifetime walking its streets.

The architect and filmmaker James Sanders argues that while New York is a great literary city with nearly two centuries of novels, short stories, plays, essays, poems, and songs exploring its inhabitants, landmarks, and enduring myths, it’s an even more perfect movie city because of its anxious restlessness and adventurism—“ideal for the constantly moving images that make up a film.” Movies, he writes, are “the city’s true mythic counterpart.”

The city was a vast film school for moviemakers and moviegoers. Repertory film houses like the Cinema Village and Bleecker Street Cinema, in Greenwich Village, and the Thalia, Symphony, and New Yorker, on the Upper West Side, offered the equivalent of a full-scale, constantly repeating film history course at bargain prices. In the early sixties, future director Martin Scorsese and auteurist critic Andrew Sarris shared office space in a second-floor walk-up at Eighth Avenue and Forty-second Street, the butt end of Times Square, to be near the shabby movie houses where for a quarter they could catch double features and new films from Europe. Folksinger Phil Ochs and his pal Marc Eliot, the future author of a book about the rise and fall of Times Square, saw John Ford’s Fort Apache and The Searchers, both starring John Wayne, while Bob Dylan, newly arrived from Minneapolis and pining for Suze Rotolo, his as-yet-unattainable girlfriend, took in Atlantis: The Lost Continent and King of Kings in a marathon double bill that temporarily dulled his pain. And the future cultural critic Phillip Lopate cut high school classes to see Jean Renoir’s exquisite drama Rules of the Game “with my legs dangling over the Apollo balcony” at 223 West Forty-second Street, the most successful art house for foreign films in the United States.

“Each art breeds its fanatics,” recalled Susan Sontag. “The love that cinema inspired, however, was special. It was born of the conviction that cinema was an art unlike any other: quintessentially modern; distinctively accessible; poetic and mysterious and erotic and moral—all at the same time. Cinema had apostles. Cinema was a crusade. For cinephiles, movies encapsulated everything.”

Like so many young artists and cinema buffs, Jim Herlihy and John Schlesinger had each ventured to New York for fame and fortune. Otherwise, they seemed to have little in common. Herlihy was the son of working-class Catholics raised in a slowly deteriorating neighborhood of Detroit, and he barely made it through high school. He worked strenuously to keep his homosexuality a secret from his family, and found home a suffocating environment that he escaped by enlisting in the navy as soon as he reached eighteen. An aspiring novelist, playwright, and actor, the arc of his career reflected the unprecedented opportunities and turbulence of the times in which he lived. He used the G.I. Bill to attend Black Mountain College, an experimental school of the arts in North Carolina. Once he made it to New York he joined the periphery of the lively and influential gay arts community that emerged from the shadows after World War II. Blue Denim, his best-known play, ran for six months on Broadway and was made into a successful feature film. His three novels all garnered critical praise, and two of them were made into Hollywood movies.

Copyright © 2021 by Glenn Frankel