Chapter One

The barber paused, flicking water droplets from his razor with a brisk snap of his wrist.

“Well, I once shaved Governor Liu of Qin Province during the processional, and last summer, I stepped in to thread Crimson Bow’s brows when her own barber was ill.”

“Crimson Bow, the actress from Fenghua?” asked Chih with interest, and the barber made a humming noise of assent as he rubbed a little more oil into their scalp. The first slide of the razor against Chih’s head sent a not altogether pleasant shiver through their body, but they took a deep breath and sat as still as it was advisable to sit when a large man held an enormous sharp razor that close to their face.

“Yeah. Her company, the Resplendent Sky-whatever, they were touring up through Vihn. They were doing that play, you know, the one about the marriage of that sect leader in the down-country.”

Chih sat very straight as the barber recounted the plot of The Cruel Wife of Master See, because after all, reviews and criticisms were their own kind of history, but the quick rhythmic movements of the barber’s razor put them into something of a daze. The sharp blade glided over the curves of their scalp as if it intimately knew every bump and hollow, and the tingles that always ran up Chih’s spine and, for some reason, behind their knees, when they got their head shorn gradually took up all of their attention.

It seemed no time at all before the barber whipped the old muslin cape off of Chih’s shoulders, nodding with professional satisfaction.

“—and, of course, I shaved the four Gao brothers, the bandits of the Carcanet Mountains, but that was after they were dead. Give it a feel there, see if I missed a spot.”

Obediently, Chih ran their hand over their head, marveling at the smooth skin that replaced the inch or so of growth that had sprouted since they left the Singing Hills abbey early in the spring. The tent was littered with greasy bits of black hair, and their scalp was silky smooth and perfumed with a touch of jasmine oil.

“Now, you’ll want to wear a scarf or a hat over that. It’s not used to the sun anymore,” the barber recited, and Chih nodded.

“I know, thank you. But what were you saying about the four bandit brothers?”

“They tried to poison some imperial inspector, and she tricked them into eating the poison instead,” the barber said dismissively, glancing over through the open tent flap at a shaggy man carrying a load on his back. The short woman accompanying him, her own hair impeccably coiffed despite her traveling clothes, made a hurry up gesture, and the barber nodded to her.

“Right away, ma’am,” he said.

Chih found themself gently pushed outside the tent where a rufous-striped bird hooted gently from a nearby hitching post and fluttered over to settle on their shoulder.

“There,” Almost Brilliant said with some satisfaction. “Now you look like a proper cleric again.”

“I’m exactly what a proper cleric looks like. Do you know anything about the Gao brothers, bandits in the Carcanet Mountains? Ate poison they intended for a female imperial inspector?”

“I cannot say that I do. Should you go back for the story and to have your brows threaded as well? They’re getting rather—”

“I’ll go back when he’s less busy, and my brows are fine. Anyway, I’d rather spend my money on some lunch than on the privilege of crying in a barber’s chair.”

“If I had eyebrows, they would be perfect arches, just like the doorways of Singing Hills,” Almost Brilliant grumbled. “But I suppose you must have your treats.”

“Your eyebrows would rival the path of the moon itself,” Chih said gallantly, heading for the inn that they had spotted coming in to town.

“Flattery, cleric,” Almost Brilliant said primly, but she didn’t protest when Chih pushed open the curtains that hung over the door of the Running Fox. Unlike the timbered buildings on the street, the Fox was built up from stone, and Chih wondered where the stone had come from, whether it was scavenged from some other place or if it was a remnant older than the rest of the village.

Inside, the Fox was clearly undergoing some kind of renovation. There was a pair of workmen in the scaffolding leading up to the roped-off loft section and a layer of sawdust coming down to cover everything that wasn’t sheltered under a suspended cloth or being aggressively wiped down by the waitress.

“Over there under the tarp, please, cleric,” she said. “We’ve got tea and fried bread for now, and if you wait just a little, we’ll have some chicken chao as well.”

“Tea for now, and I’ll have the fried bread with the chao whenever that’s up, please.”

There were two young women at the table opposite the one Chih took, so different that they couldn’t even have been mistress and servant. The smaller woman was dressed in light silk robes in pale blue, her long hair swept up by a small brassy cornet and allowed to stream loose down her back. She sipped at her earthenware teacup as reverently as if it were a sacred elixir, and she sat with her back as straight as the iron pillar at Wei, scorning to touch anything as common as the back of her chair.

Her companion, on the other hand, was ready for the field with the ends of her plain hemp robes hitched up to her belt. She sat with her sandaled bare feet tucked into the rungs of her chair, and she leaned forward with one arm on the table, dipping the end of a fried breadstick into her tea and eating it in large bites.

Despite their differences, the two seemed entirely at ease, and as they waited for their own food Chih watched them curiously out of the corner of their eye.

“We could follow the ox road to An-ti and take a barge downriver,” mused the girl in hemp. “I wouldn’t mind a while to kick back on a barge and watch the riverlands go by.”

“Oh, but sister, that would take so much longer, six days or so at least. It would be faster to take the foot road immediately west, and then we wouldn’t need to pay for the barge. Were you not saying that we must be thrifty only last night?”

“I notice that you’re only worried about thrift, sis, when there’s a water crossing involved. I promise, the Huan River is big and slow as an old sow, it won’t be like the storms you’re used to.”

The girl in silk opened her mouth to reply, but a crashing sound brought her up short. Almost Brilliant peeped in surprise, exploding in frantic wings to sit up on the edge of the tarp, and when they turned, Chih saw what they guessed was their tea splashed on the chest of a large man in the leather clothes of a miner. The man was roughly the shape of a boulder himself, and in his hand, the waitress’s wrist looked as delicate as a flower stem.

“Watch where you’re going, what kind of place is this?” the man growled, giving her a brisk shake. “You think you get to go running around like this is the damned circus?”

“I said I was sorry,” the waitress protested, trying to jerk back, but the man refused to let her go, shaking his head and snorting like a bull getting ready to charge.

“You can’t treat people like that,” he said, and even before Almost Brilliant called with growing alarm, Chih stood up, smiling and opening their hands.

“Ah, actually, given that it was my tea, I feel that I have cause to be upset here as well,” they said, approaching the tense pair. “Why don’t you let the young miss go get us both some more tea, and then I can help you get cleaned up?”

Up close, the man was even larger than he looked from a distance, but Chih ignored their instinctive urge to pull back. Their shaved head and indigo robes screamed cleric in almost every corner of the empire, and no one really needed to know that the Singing Hills abbey was more about history than it was about religion and common aid.

“Why don’t you get us a round of dark smoky tea, my dear?” Chih continued brightly, turning to the waitress and ignoring the man’s glower. “Something nice and hot, and I’ll get this fine man cleaned up.”

The miner’s grasp loosened on the waitress’s wrist, and Chih was just congratulating themself on a neat job when the man turned and shoved them hard in the chest. Chih fell back against one of the tables, the hard edge jabbing painfully into the small of their back.

“Mind your own damned business, stinking jackal-cleric,” he snarled, his face going red, and Chih was just beginning to calculate how very badly they might have played this when the young lady in pale blue slammed to her feet.

“How dare you!” she cried, her voice like a clarion chime. “How dare you lay hands on a young girl who only tripped, and again, how dare you abuse a cleric, a holy person!”

Chih could practically feel the situation slip sideways on them. If the man wasn’t going to be swayed by the kindly intervention of a cleric, the chances he could be moved by a young woman with only outrage on her side were very low.

“Shut up,” the man snarled, turning towards her with a maddened gleam in his eye. “Shut up, shut your fucking mouth—”

“Miss,” Chih said urgently, “perhaps it would be best if—”

“What barbaric manners, what lack of respect!” the girl said, unheeding. “The beasts of the field act more correctly than you do, and—”

Chih barely sidestepped as the man roared with fury and charged, and whatever good intentions they might have had were soundly ruined as they tripped over a stool and landed flat on their rear. Above them, Almost Brilliant shrilled in panic, and Chih was just regaining their feet when the slender young woman picked up a chair and threw it straight into her attacker’s face.

The man howled as a chair leg caught him in the mouth, splitting his lower lip and sending a shower of blood flying, but he lunged towards her again. Chih stepped back, because whatever was happening was well beyond their scant authority as a historian or a spiritual adviser, and a firm hand grabbed the sleeve of their robe, hauling them back and towards the curtained doorway to the kitchen.

“Welcome to the riverlands, cleric,” said the waitress with grim amusement. “You need to learn when to let your tea go.”

She dragged Chih into the kitchen where a tired cook was chopping up a thumb of ginger while occasionally stirring a large pot of boiling rice.

“What’s happening?”

The waitress only rolled her eyes, pouring them a fresh cup of tea.

“If the big fucker wins, we’re probably in trouble, but that’s not going to happen.”

Chih took the tea—smoky and dark like they had been hoping for—and peeked through the curtains at the mayhem sweeping the front room.

The big man and the young lady had smashed their way through one of the tables and two more chairs, leaving the floor littered with wreckage. The man clutched his arm and reeled back to the center of the inn, bawling curses that echoed off the high rafters. To Chih, this would be the perfect time to make themself scarce, but the young lady only closed the distance, her fists clenched.

“What impudence!” she said, with the kind of diction that could get away with saying things like impudence. “People who abuse those smaller and weaker than themselves deserve the lowest, cruelest halls of the dead king!”

He took another swing at her, a right hook that wound all the way back and came forward with enough force to level a city. It would have broken the young lady’s skull to pieces if she was there when it landed, but of course she wasn’t. In a swirl of silk like a storm, the young lady leaped into the air, throwing the end of her stole over a rafter and lofting herself up like an acrobat.

The man, propelled by his own uninterrupted rhythm, grunted as he lurched forward, and delicately, the young lady’s pointed foot pushed off his shoulder, swinging her back. When she swung forward again, it was with all her weight behind her heels, directed perfectly at the man’s head.

He went down like a felled tree, practically shaking the inn to its foundations. The young lady calmly let go of her stole, coming to land with a feather’s grace on his chest. Her face was still but there was something restless about her eyes that made Chih think of hunting hawks, of endless hunger and winter-sharp ferocity.

“So,” Chih found themself saying, “do we clap, or do we run?”

The waitress patted them on the shoulder.

“Well, now Hien and I need to remove the big fucker from the floor. You can go have a seat, cleric. Your food should be out in just a bit.”

The young lady stepped down graciously as the waitress and the cook went to drag the man out the door. He was whimpering now through a broken mouth and a nose that was already starting to swell to enormous proportions, and he went without protest. Chih stepped out into the main room, and Almost Brilliant alighted on their shoulder, her claws digging harder into their skin than usual.

“Southern Monkey,” Almost Brilliant hissed quietly, and Chih blinked at them.

“What?”

“That was Southern Monkey style,” Almost Brilliant insisted as if Chih had tried to argue. “The thing with her stole, my mother saw it in the Verdant Islands, I would swear to it. There were only eighteen practitioners of Southern Monkey style eighty years ago, and nine of them were in their early hundreds. It is absolutely Southern Monkey style.”

“Do you want me to get you her autograph?” Chih asked, biting back a smile, and got a swift retributive peck to their earlobe for their humor.

Deprived of her prey, the young lady had returned to her table, sitting back down to her tea even as her companion pulled out a worn leather pouch to count out some coins.

“Well, at least it was only a few chairs and tables this time,” she said. “And this stuff looks pretty old at that, so let’s see, ten and a quarter should cover it…”

“Are they going to make you pay damages?” asked Chih, taking a seat at their own table with their tea.

“Of course they won’t. They’re too afraid that Lady Heavyweight here will bring the place down around their ears if they piss her off.”

“And of course we will pay the damages,” said the young lady serenely. “We move through this world only with the grace of others, and we must pass without the least ripple.”

“No ripples, but broken chairs and broken heads, those are fine. We were trying to keep a low profile, sis.”

“Who is going to talk about a little lunchtime disagreement? That is all it was.”

The girl in hemp looked like she wanted to argue, but then she shook her head, giving up for the moment to turn to Chih.

“Are you all right, cleric? You took a pretty hard fall. Nice try on stopping things from getting out of hand, though.”

“Thank you, and I’m fine, just a little sore and a little foolish. I’m Cleric Chih from the Singing Hills abbey, and this is my companion, Almost Brilliant.”

Chih opened their palm so that Almost Brilliant could hop down to perch on it, sweeping her wings open and tocking her head in a small and utterly unhumble bow.

“My pleasure,” she said, and both women blinked at her speech.

“Oh, a neixin,” the young lady in silk said. “Then you must be a scholar as well as a cleric.”

“Say rather a historian and observer, and I have certainly observed a wonder today. May I ask for your names?”

The young lady rose immediately to her feet, clasping her right fist in her hand and bowing low. It was a martial form of deference, and Chih belatedly stumbled to their own feet to return with a bow of their own.

“Honored cleric, I am Wei Jintai of the Fengxi Wei in the Verdant Islands, martial daughter of Yo Laozi.”

While still bowed, Wei Jintai lifted her foot and gently mule-kicked the chair that her companion sat on, bringing her reluctantly to her feet as well. The other woman bowed curtly.

“I’m Sang,” she said diffidently. “I’m just here to manage the money.”

Wei Jintai straightened up, frowning with irritation.

“This is my sworn sister, Mac Sang,” she said. “Please, mistress neixin, if you remember us unworthy wanderers at all, please remember that.”

“It is my duty and my honor, Wei Jintai,” chirped Almost Brilliant, and only Chih knew her well enough to see how she was practically quivering with delight.

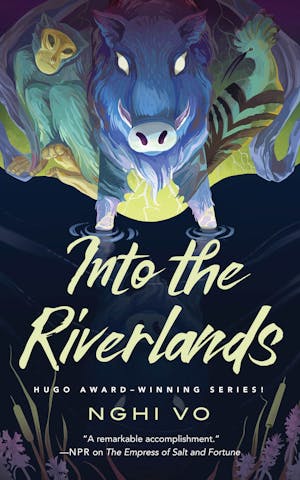

Copyright © 2022 by Nghi Vo