• I •

WHEN I was a child, the dead were all around us. Cemeteries were not common in the early years of the 1830s. Instead, small, shambling family graveyards butted up against barns, or sprung up like pale mushrooms at the edges of pastures, in the yards of church, and school, and meetinghouse—until eventually you could look out across the village, see all those gravestones like crooked teeth in a mouth, and wonder who the place really belonged to, the huddled and transient living or the persistent dead?

Many folks found this proximity to death and its souvenirs discomfiting, but my father was the first gravestone carver in the village of Stratton, New York, which meant that the distillation of death and grief into beauty was our family business. Death, to me, was tied inextricably to cherished things: to craftsmanship and poetry, to my father and to the beautiful things he made, and I couldn’t help but feel some tenderness for all of it. Even all these years later, I can still see those gravestones vividly. Drizzle-gray slabs of slate, smoothly planed and cool to the touch; grainy sandstone in its striated shades of red and brown and buttercream; soapstone soft enough to etch with a thumbnail, yet somehow able to resist the assaults of time and the elements; letters and symbols, crosses and cherub wings, and forlorn-looking skulls chiseled delicately into the surfaces; beveled edges smooth and sharp beneath the pads of my small, inquiring fingers.

Like the works of his hands, my father also remains vivid. When I remember him, he is working, always working, at his craft. His eyes and hands search a great heft of rock for its secret seams, and then, with wedge and mallet, he splits it open as one might split an orange. With great focus, he hammers at his chisels, patiently lifting away slow, stubborn ribbons of schist like potato peels to carve the rounded tympanums. With pick and file, he etches and sands and then blows the glittering mica dust into the air. Noticing me, his watchful daughter standing in the doorway, he looks up and smiles, but his hands are ever diligent; they glide along surfaces, feeling their progress.

When I was very young, I would go about with bits of stone in my mouth, enjoying the feel of the rough grain against my tongue. I have few memories of my mother, who died giving birth to a baby who died with her, but one of the memories I have is the sudden indignity of her finger in my mouth, swiveling roughly, fishing a piece of rock from it. Then she too became a gravestone: creamy yellow, reticulated by thread-thin veins of iron, embellished along the side panels with fine scrolls and rosettes, and with a centerpiece inscribed “Loving Mother,” all of which I remember in greater detail than I remember her.

I am fond of those memories of my father, his shop, his gravestones, but they are tied to other, darker memories, and the mind, that imbecilic machine of associations, moves irresistibly from one to another, and before I can stop it, I am seeing myself and my brother, Eli, in a different shop, the smith’s forge. I’m ten years old, my brother fourteen, the age of each of our deaths, and we’re surrounded by our grim-faced neighbors who, out of the firm conviction that it will cure us of our afflictions, are forcing us to swallow the ashy remains of our father’s burned corpse.

The fact is that I was a child at a hideous time, when the terror of death suffused all of life and against it people had little recourse besides their own dark imaginations. More than a hundred years had passed since the Salem Witch Trials, and still the habit persisted of encapsulating what was feared in stories. Stories, after all, have boundaries, and fear needs nothing more desperately than boundaries. Thus, a crop failure or injury might be construed as the work of demons, or the fruit of some unholy pact with the Devil, or punishment for one’s own unconfessed sin. This was why when the wasting death—what is today called tuberculosis—came to our town, it arrived wrapped in a shroud of stories that were passed, like the disease itself, from hand to hand until they had both spread to nearly every town and village along the Eastern Seaboard.

The restless dead, it was whispered, were crawling up out of their graves at night and preying upon their own family members, dragging them down ounce by bloody ounce into the graves beside their own. This explained why entire families would crumble, one by one—strong, vigorous men and women watching their flesh fall suddenly away, their eyes receding into their skulls, the coughing and the blood. Who could blame people at a time when nothing at all was known about bacteria or the virulent microscopic droplets that sprayed forth from a sick person’s cough, for seeing a perverse and ungodly malevolence at work—pattern, design, intentionality—in an entire family’s slow, hideous demise?

This narrative of the malicious dead not only offered an explanation, it also suggested action that might be taken to stop what seemed unstoppable: if the dead were not quite dead enough, then the solution perhaps was to dig them up and put them more conclusively to rest. Exhumations began. When the second wife of the cooper fell ill, the deceased and famously jealous first wife was dug up for interrogation. On it went from there. Coffins were pried open, corpses examined, their appearances quarreled over. Why did the Wesley daughter, dead from scarlet fever in the early winter, look as though she’d been buried only the week before? Never mind that winter was only just relenting, and the girl was probably coming out of months of deep freeze, her flesh rosy with thaw. Why take chances?

People who knew, people with close ties to Europe and its intricate lore—young brides recently arrived from Häggenås and Blåberg, a grandfather from Lovön, a nephew from Bistritz—advised the rest on the best course of action.

“Break the arms and legs to keep them from crawling about in the dark.”

When one measure failed to stop the descent of the living toward death, a new measure would be offered.

“Carve out the heart and examine it for the fresh blood of its victims, then you’ll know for certain.”

Then, “What use is certainty and how can it ever be had when you’re dealing with the unnatural, the unholy? Cut off the head, and that will be that. To be safe, burn the heart as well. Then have all the remaining family members eat the ashes. Make the bodies of the living inhospitable, from the inside out, to the demonic.”

My father, the gravestone carver, had spent his life helping folks make peace with death and he regarded this war with abhorrence, insisting at every opportunity in his gentle but stubborn way that our dearly departed bore no responsibility for the afflictions of the living and that fouling their bodies was a sin and an abomination. He may have persuaded some, but those who opposed him were louder, and when he too began to cough, I saw an ugly satisfaction in the eyes of those he’d reproved.

Deacon Whilt was one of these. The man, who had appointed himself commander in the war against the undead, and who took officious pleasure in bearing the arms of holy water and crucifix to the exhumations, came one day to my father’s shop. He ambled about, picking up chisels to squint at their varied ends and knocking his head on the iron tools that hung by hooks from the ceiling.

“Word has it,” he said, massaging the back of his skull where it had encountered the long metal handle of an adze, “they found a ghastly one over in Plattsburgh. Fat as a tick on a mule. Blood all over the creature’s hellish mouth. They pierced the stomach and hot blood poured out for near an hour.”

“And you believed this?” my father asked between hammer blows.

My brother, beside him, had paused at his work and was listening, open-mouthed and horrified, but a stern glance from my father flushed his cheeks and set him back to work.

The deacon frowned down at a smear of dust that had marred his black cassock and, taking out a handkerchief, began to sweep it off with controlled violence. “And what would you have me believe? That it is all mere coincidence? Six families in the next township, nine in our own, falling like a child’s arrangement of dominoes—by chance?”

My father did not answer, and the deacon sidled up beside the stone my father labored over.

“Such lovely religious sentiments on your gravestones, Isaac, and yet their maker seems to deny the active influence of the supernatural in the affairs of this world. I might almost imagine you lacked a godly dread of the Devil and his works.”

“Or imagine instead that I possess trust enough in God to drive out fear of a multitude of devils—real or imagined.”

My father might have said more, but a cough welled up from deep inside his chest. He tried to hold it back, but finally could not and lifted his smock to hide the fit until it passed.

The deacon watched my father, his expression softening in a way that disturbed me more than his previous hostility.

“Your apron, Isaac,” he said when my father had finished. “There’s blood on it.”

My father turned back to his work.

“Would that you might turn from your stubborn unbelief,” Deacon Whilt went on, “which gives the demons free entry. We’ve lost half of our men already. Half again are as ill as yourself. At this rate, the village won’t survive the winter. We need you well, and Eli too. We cannot afford to lose any more. Not one more.”

He went to the window and gazed out at the two distant graves perched atop a hill and silhouetted against the pink blaze of the setting sun. My mother and baby sister.

“It is a vile business. On that we are agreed, but then the powers of hell are vile. We do what we must, not because it is pleasant, but because it must be done. You will have to dig them up.”

“No,” my father answered without pause or glance. “Never.”

The deacon turned and let forth a sigh of great weariness, then made his way to the door. When he noticed me standing nearby, he put a damp hand of blessing on my forehead, which I struggled to endure without scowling or drawing away.

“I do hope you reconsider, Isaac,” the man said without turning. “You’ll all die otherwise.”

* * *

“PAPA?”

The deacon had gone and my brother was out filling the wood box, and my father and I were alone in his shop with the light falling and the hunks of stone set up on tables like islands in a stream. He was at a desk writing, something he did rarely on anything other than stone.

“Papa, what are you writing?” I asked, coming up beside him.

“A letter.”

“A letter to whom?”

“To your grandparents.”

“My grandparents?”

“Grandmother, anyway, and to her husband, Mr. Vadim Semenov.”

“I did not know I had grandparents.”

“You do. You met them once, but you were young, perhaps too young to remember.”

“Why did I meet them only once?”

There was a moment of hesitation as my father tried to find the right words.

“Your mother loved her father very much. He was a good man, a minister, very pious and kind. After he died, your grandmother married again. Your mother was unhappy with the match.”

“Why?”

“It came about rather … suddenly, and strangely. He is an unusual man.”

“Unusual how?”

“Well, he’s…” My father cast about uneasily and finally settled on, “He’s no Protestant. I’ll say only that. It’s what upset your mother. She never imagined your grandmother would agree to marry a Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox, or whatever he is, though the man was—is, I imagine, still—quite wealthy and quite persuasive, but she did, without hesitation or discussion, almost as though she were … sleepwalking into the match. I’ll grant you, it was strange. None of that seems quite so important now, though. I think even your mother would agree.”

I looked down at my hands, where they nervously fingered a loose thread on the pocket of my apron, afraid to ask the next question.

“Why are you writing to them? Now? After all this time?”

My father turned to look at me and reached out for my hand, and the understanding that passed between us in that look and in that touch was so painful and clear that I could have believed that people did not need words to speak at all.

“Are you going to die, Papa?” I breathed. “As Deacon Whilt said?”

He looked down into his lap, took a rattling breath, collecting himself, then looked up at me again, a soft smile in his eyes.

“Be assured of it,” he said. “As will you, as will everyone else you or I know.”

He gestured with the feathered end of his quill pen at the gravestones leaned up against the walls of the shop in various stages of completion.

“We all pass from this world to the next, dearest: it is our lot as mortals and our privilege, and if the choice were mine to do it sooner or not at all, I’d not hesitate to choose sooner and be sooner in the presence of our Lord. You mustn’t be afraid of death, Anna.”

“I know all that, Papa. You know I do. And I’m not afraid of death, but I am … I am afraid of…”

I hesitated, struggling suddenly to speak. Overcome, I looked away, trying to tamp down the fount of breathless fear and tears pushing up forcefully in me.

“Afraid of what, dearest?”

My father opened his arms, still lightly white with rock dust, to me.

“Afraid of you going without me,” I said, stumbling forward into them, “afraid of being left behind, without you.”

Once in his arms, a kind of panic seized me, and I clung to him.

“I wish we could die at the same time,” I whispered.

My father held me tightly for a long time in silence. Finally, he cleared his throat and wiped his face with the rag from his pocket.

“Our days are numbered by our maker,” he said, his voice husky. “He’s a number for me and a number for you, and each one holds a blessing if we’ve the courage to find it. You must not wish a day of it away. Though it’s difficult, we must trust ourselves and each other to his gracious providence and his wisdom.”

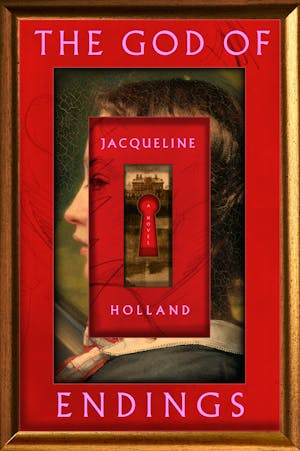

Copyright © 2023 by Jacqueline Holland