ALICE

It makes you sick.

This room, it makes you sick. It makes me sick. It’s all angular and wrong, and the angles join in conversation with each other. They become hateful. They begin to tell you that they hate you and that they want you to die, somehow, that maybe they’ll be the ones to kill you, or maybe they will convince you to kill yourself, with words, economic manipulation, gentrification, every weapon at their disposal. Because you didn’t deserve to live, at least not here, in this room, in this building, in this part of the city. You should go somewhere else. You make us sick, the angles and the walls say, you’d be better off far from here, or dead, or both.

I hate living here. The rent is okay, I suppose, but the heating doesn’t reach the top floor, where I am. On cold days I can see my breath in the air. And the inside of the windows fills with condensation, the corners of the room with creeping mould. I emailed the landlord about this, during winter, with my duvet wrapped close around me, and he responded telling me I needed to air the flat out by opening up the windows. But that’s not really why I hate living here. This flat, and my bedroom in particular, reminds me of another place, another room in another part of the city. It doesn’t look much like that place. It looks like a normal flat. Messy. Too messy. It’s not really in how the place looks, but it feels the same, I can feel the air pressing in all around me, eyes watching me. Maybe that’s why I moved in. This flat doesn’t hate me, not really. Its hate is only a pale imitation of real, true hate. This room is not passionate. It still hates, but it only hates because, well, what else is it going to do. How else is it supposed to feel about me? Rooms sit and stew. They take in the things you do in them. Their walls soak up every action you take between them, and those actions become part of the bricks and the plaster. Maybe I made it hate me. I can be hateful, to myself and to others. I try not to be. I try to be better. I have to believe that everything I do has a destination to it, that everything I do means I have control, over my environment, my relationships, my life. My job, if I had one.

I move flats a lot. I don’t feel comfortable staying in the same place for long, and in every house or flat that I’ve been in for the past five years, there has been a room where the house or the flat is concentrated to an absurd degree. In that room, the air grows thick and the spirit of the building becomes near-physical. The less rooms you have in your flat, the more concentrated this is. The less income you generate, the less rooms you can have in your flat, the thicker the air, the more hateful the atmosphere. I don’t know if this is how it really works but it is what I tell myself.

I don’t have many friends, but last year I began to ask whoever I could about hauntings, in the vague hope that somebody would understand what I meant when I said ‘hauntings’. Most people have a ghost story of some kind, even if they don’t believe in ghosts. Maybe their Great-grandma came to sit at the end of their bed for a month after she died, or they heard footsteps from the attic where there couldn’t have been anyone to make them. I’d try to ask casually, at bars or on the internet, have you ever experienced a haunting? I made sure to phrase it like that. Not have you ever seen a ghost? I wanted to know about hauntings, specifically. One common thread which interested me was that many of the people who answered said that their places of work were haunted. This was actually more common than peoples’ houses being haunted, which I thought was strange, but then again, Bly Manor from The Turn of the Screw was a place of work for the Governess and every big imposing house in the country has people working in it, cleaning, cooking and these days, now nobody lives in them, giving tours, maybe acting out scenes for tourists.

One girl told me that she worked as a cleaner for some offices which were housed in this absurdly tall old townhouse. She had to clean a few of the rooms, kitchens, toilets, but mostly the stairs, which wound up and up in sharp lines like a tower. But, after a couple of shifts, something strange started to happen. When she cleaned the lower landings and stairs, she could hear somebody doing the same above her. Moving about. Opening and closing doors. Vacuuming the floors. She could hear their footsteps on the hard wood of the steps, echoing down from above. She thought this was strange – she had been told she would be working alone, and the sheet in the downstairs reception had said that everybody who worked here had signed out. When she ascended the stairs to work on the offices up there, and see who it was that was cleaning, everything was deserted, and still dirty. She stopped and listened then, and heard somebody below, cleaning the floors that she had just done. This happened every time she cleaned at that place. She wrote an email to the manager of her cleaning firm about it, but the only answer he had was that, well, maybe it was just noises from the building next door. That was probably it … these old buildings have funny echoes. But one time, she said, she heard the person above, she could hear their feet on the floor clear as anything, and it was too much. She’d had enough. The girl ran up the stairs to catch them, because she had to know, desperately, what was happening to her. They were still making noise as she ascended the stairs, growing louder and louder until she got to the top floor. The noise was coming from a room at the end of the landing. The door to that room was shut. She called, “is anybody there?”, and nobody answered, of course. She walked down the landing, shaking, just a little bit. The door was locked, but she had a set of keys, one for every door in the building, or so she’d been told. There was still noise coming from inside the room. A long, agonising scrape as some item of furniture was pulled across the wooden floor. An unidentifiable thumping, and footsteps moving back and forth. At one point, she heard those footsteps get closer and closer to the door, and she looked down at her hands to see that they were shaking uncontrollably, before the steps moved away again, over to the other side of the room. She had cleaned this room in the past. She knew that one of these keys worked, but she couldn’t remember exactly which one. There were small silver keys on the ring, and big, bronze-coloured ones, strange little ones that opened the bins out at the back of the building. Keys of every type. She wished she had made a note of which one worked for this, the last door, but she hadn’t. That could have been it. The girl could have left the noise a mystery. But … when she told me this story, I asked that. Why open the door? Why did you need to see what was in there? She shrugged, and said she wasn’t really sure, beyond the fact that this was her workplace, she felt unsafe, and she had to know why. So, the girl tried every key on the set, and, of course, they all stuck in the lock. Sometimes they stuck fast, and she had to pull hard to get them out again. This happened every time, until she came to the last one, which was big, golden. She put it in the lock, her breath rattling in and out. Then, at the last moment before she turned the key, she pulled it back out. She couldn’t do this. She wasn’t strong enough. But she still wanted to see … she bent down, so that her face was at the height of the keyhole, and peered through.

Do you know what was in there? Do you? Do you want to know? I know what you want to know and maybe what you want it to be, because I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this, trying to reconstruct the circumstances of a haunting in my mind, and you want it to be nothing in there. You want her to look through the keyhole and find it empty, and then open the door with the key. You want her to walk around the room but find nothing out of place or strange in there at all. You want her to go to each wall and place her hand on the red wallpaper and feel a throb inside. Maybe see shapes in the old stains on the wallpaper. In all honesty, I would also like that to be what happened in the story. I asked for stories about hauntings to feel less alone, to feel less like an outsider from everybody around me. But that isn’t what she found. Instead, she found a woman in there, who had been cleaning out her desk. This was her last day and she didn’t want to leave things looking like a mess. She apologised for any distress she may have caused.

It feels like an anecdote that was meant to describe something, a metaphor about late capitalism, hauntology, about how work turns us all into ghosts, repeating the same learned actions over and over again for eternity. For that person, the wonder and the possibility and the horror of a haunting was just, in the end, somebody else doing their job for them.

The other thing is that this anticlimactic event only explained that one particular instance of hearing the noise. It did not explain all the other times that there had been sounds of somebody else in the building. There can’t have been somebody moving out of those offices every single time she had a shift there, surely? She didn’t sleep well when she thought about that. The girl told me that, afterwards, she requested to be moved to clean somewhere else. Every time she entered that building and looked up at those stairs, she felt queasy.

I have to believe that other people have also experienced impossible, horrible things.

I have to know that there are people who would understand if I talked to them. I have to know. I have to believe that my trauma is relatable, if controversial, that there are people who would listen to me and go, it’s okay Alice, it’s completely okay. You are so fucking normal. Everything you’ve experienced is normal. But soberly I think that, really, the only person out there who could ever understand is Ila, and I can’t talk to her. I just can’t. We used to be so close, but I can barely think about her now without having an anxiety attack. It’s probably the same with her. I don’t know for sure, but going from the sort of things she says now, if she thinks about me at all it is to hate me. I tried to be brave. She was a guest, recently, on a program on BBC Radio 4, and I really did try to sit and listen, as a form of exposure therapy. I turned it off after five minutes. I’d heard enough, and I had to smoke a joint to stop myself from passing out. Ila probably wants me to die. That’s okay. I don’t want her to die. I hate her, yes, I despise her with all my soul, in ways that it is hard to put into words, but I don’t want her to die. I’m a good, forgiving person, I’m lovely. I live in this flat in this terrace house with all these hateful angles, and they remind me of another house, with other angles, angles that hate you more than it is even possible to comprehend, angles that crawl inside your brain and inside your body and move you around of their own accord, that make you see, think and feel things that nobody should ever have to see, think, feel, know, believe in. Angles that indicate the building you are in is not even really a building, that no human could have possibly thought of this when building it, that this house simply came into being from contact with the pure, violent terror that can only exist in the very worst examples of humanity. And that horror is transmitted through you, a little thing inside the heart of the place. It cuts its way into your body, or uses somebody else to cut its way into your body. I have a scar on my forehead to attest to that, and Ila has a scar on her stomach. And Hannah. Something happened to Hannah. The place, it worms into your brain and your heart. By the time I got out, I was different. The me who sits here right now in my room isn’t the same me that went to University, went to all those parties, met a girl called Ila.

Ruined her. Got ruined by her.

My room isn’t big. It’s just too large to not be cosy, but not large enough to be spacious, in Estate Agent terms. When I moved in, I found a mark in the paint of the wall opposite my bed that I could have sworn hadn’t been there when I viewed the flat. I took a picture of it and made sure to send it to the landlord, so he didn’t try to charge me for it later when I needed to move out. I couldn’t work out what the mark actually was, and it unsettled me, so I covered it up with a poster for a band that were popular a long time ago, before I was born. In the poster, four boys stand in front of a brick building. One of the boys is centred, the frontman of the band. The overwhelming personality, eclipsing the other three with ease. His hair sticks up, and he holds a branch in one hand sprouting white flowers. His heart aches. You broke his heart. He’s miserable, and he sings about how everything makes him miserable. The meat industry, it makes him miserable. I don’t know why I had the poster, honestly. I used to love the band … I still love the band. But I don’t remember where the poster came from, it was just there, amongst all my stuff when I moved in here. So I put it up on the wall, over the blemish in the paint, thinking that would solve everything.

This was a mistake. After living here for about a month, my sleep started to dry up. That was it, at first, but I could feel that something was coming, and there was nothing I could do. Then he started to appear. Sometimes, at night, in the dark, when I can’t know for sure if I am sleeping or lucid, the man, the one with the hair and the jawline, he crawls out from the poster, he stands over my bed, the flowers still in his hand, and he flickers in and out of focus. He pushes out from the past, away from his bandmates and into the now. He wants me. After this happened a couple of times, I blacked out his eyes with biro. Now, when he leaves the poster, he has no eyes, which looks terrifying but isn’t as terrifying as it was when he had eyes. Think about it – think about the man, the one you picture in your head, with eyes. Stop and think about that for a moment.

When I moved in, I burned sage (after turning off the fire alarms), I made pieces of paper with my own private inventions drawn upon them and put one under each piece of furniture. Underneath my bed I placed a sheet with five black ink intersecting circles, which represented the boundaries of the room, the building, my physical body, the astral plane and my soul, which now must be saved. Inside the circle for my soul was an italicised a which represented my attempts at repressing my own trauma. This is a sort of private spell; not a legitimate charm of any kind, but one which I invented to control my own hauntings, or at least to try and control them. Maybe it does nothing at all. But it’s good to feel in control of your environment. Of course, sometimes the singer still exits the poster and stands there, without sight, shifting. If I lay very, very still I know he will not come near me. I don’t know what would happen if he came near me, but I know that I don’t want to find out. The closest he has come is there at the end of my bed. I think maybe, if he did approach me, he would try to black out my eyes. With a pen, if he could find one. Maybe he would try to do it even without a pen, maybe he would do it with his fingers, pushing them into my eyes, singing the whole time, not singing properly, opening his mouth and having the songs come out without him moving his lips for the words, like there is a speaker inserted into his throat that plays when he opens his mouth, pushing his thumbs into my eyes, last truly British people, and when he is done with my eyes he would grab my mouth to put his words into it, panic on the-, whilst images of imagined atrocities that he has made up play in my head. A van, swerving sharply into a crowd of police officers, crushing their bones beneath its wheels. A man suddenly rising up on the tube, swaying a little with the motion of movement before running down the length of the train, swinging a sword along a row of commuters. A man, anonymous, shooting at a pushchair. A teenage boy walking to the front of the class and cutting his teacher’s throat with a knife. Two trans people walking together bold and defiant but then a bomb explodes next to them and their brains and their limbs scatter over the streets like snow. These images grow bloodier and bloodier until they are pure red and there are no figures in them at all, just dripping, wet redness. I become overwhelmed and throw up, realising that I cannot see, and cannot speak words that are not his, or think thoughts that are not his. This is what might happen if he comes to me. I have been careful to ensure that he can’t get that close. I know how to protect myself. He can crawl out of the poster but he cannot come near me, because I know to lay very, very still, because I have placed the right sigils in the right places, which stop him from getting to my eyes and my mouth. Lay still. Hold your breath. Don’t look at him directly. Let him retreat back into the picture.

I put on makeup for the first time in what must be a month. When it’s not in use, the mirror on my desk is covered up with a flannel, and now I see how dirty the glass is, blotched with spots of sticky residue which have been gathering dust. I try to wash it, but only make it smeared. Through the blurriness, my face almost looks okay. I’ve shaved. I put on a turtleneck to hide my Adam’s Apple. It’s hard to get the symmetry of eyeliner right in the dirty glass; that’s a job that requires a precision that, even with a clear mirror, I can’t quite manage with the tremor that runs through my hands, so I opt to avoid eyeliner, cake my eyes in red powder, put a shiny lipstick on my lips that matches. Tie my hair – too long, scraggly – back into some semblance of neat femininity. I’m clockable, but that’s okay. It’s alright if you don’t pass, a voice in me says. No one cares. The only people that care are people you don’t want to be around anyway. But another part of me, a vicious little creature that claws at my head, calls me a fucking brick sissy whispers everyone can see your stubble everyone is creeped out by you in the toilets. I tell it to shut up, try to suppress it. It’s the same part of me that looks at girls nervously sharing their selfies on Trans Day of Visibility and wants to spit bile through the screen. You’re sharing that picture of yourself? Everyone can see you’re not a woman. Everyone knows. A pale, nasty jealousy at their apparent unselfconsciousness. I don’t ever vocalise this side of me, of course. These thoughts are intrusive. I do my best to suppress them.

There’s a party which, against all odds, I’ve been invited to. There are a couple of people that I call friends, although I’m not really close with any of them, not in the way I was close with Ila and, to a lesser extent, Hannah. Ila and I had the kind of friendship where the frictions between two people soften enough that your boundaries blur. We couldn’t have been more different, looking at us, but seminar leaders would still get us mixed up, to our delight. It’s the opposite of when people think I’m some other brown girl, Ila used to say, or when they say you look like that model, despite the fact that you totally don’t, like at all. The friends who invited me to the party, a quick text at midday today, aren’t like that with me. But they’re fine. I’ve been basically a shut-in for ages now, so it’s good to go to places with people that don’t completely hate your guts.

I get the bus across town to the address Jon texted to me – with a note saying to get there at about ten because things will be really happening by then. The air outside is cold and the foxes are out at the bins at the end of my road, tearing at black plastic bags, barking their strange, human screams. I steer clear of them, and wait for the bus, which, when it arrives, is busier than I expected. Full of other people, going to other parties, some of them already drunk. I’m not drunk yet, I had a couple of glasses of red wine sat on my bed listening intently to Darkthrone and trying to calm my nerves, but it hasn’t hit me. Not with the same force that pre-drinks have hit a lot of the partygoers on the bus. When I go to sit down I realise that the seat is wet with something, vomit, splattered across the fabric and down onto the floor. A boy sat at the back of the bus lights a cigarette and fills the inside with smoke. The driver stops the bus, and says, over the intercom, that whoever is smoking has to put it out right now or he’ll call the police. The boy throws the fag out of the bus window, and on we go. The boy loudly calls the driver a word that makes me wince, and I wonder if I should say something. Hey, you. Don’t say that. Is it worth exposing myself to violence for the easing of my own white guilt? It’s not like I’m safe. If he realises what I am, he might turn his attention to me. It’s safety, pure and simple, that’s all. You have to look out for yourself. The whole bus smells like vomit and alcohol and smoke, encasing my brain in the stench. Welcome back to the real world. There are no singers pushing out from posters to haunt you here, but there is piss and vomit and men talking too loudly, enough to make your nerves tight.

I get off the bus at about twenty to ten, find a bench at the end of the same street the party’s on, and wait until it seems appropriate for me to arrive. The hosts don’t know me, only Jon and Sasha, and Leon, their twink trans guy coke addict friend, know who I am. I can’t turn up and say that they invited me if they aren’t there yet, the social embarrassment would stick in my gut. In my coat pocket, there’s a packet of Gold Leaf tobacco, so I roll a cigarette, thinking about the smoking boy on the bus, hoping he didn’t also smoke Gold Leaf. I finish smoking, stuff the yellow filter in between the wooden planks that make up the bench, and roll another. By the time that’s done, I retch, dryly, until the feeling of nausea in my throat from smoking two cigarettes in a row goes away, and I stand up, getting balance. The party isn’t far from here. It’s five to ten at night and I can’t see the moon or the stars, but I know they’re there beyond the smog and the light pollution.

I have the number of the house, but I won’t need it – all the houses on the street are quiet, many of them empty, holiday rentals in the off-season. This is close to the sea, after all. But one of the houses is alive and as I get closer, I can feel bass thumping through the pavement. The blinds are down in the windows, but I can see silhouettes of people pressed close through them, pink light shining out. It looks busy, and loud. It’s not too late for me to go. I’m cold, I’ve had some wine. I could just go home. Maybe I could get some sleep. The singer might not appear tonight. Just as I’ve decided to turn back, get the bus all the way home, I hear a voice shout “Hey, Alice!”. Jon is walking towards me, Sasha and Leon close in tow. Sasha’s white face peers through a bundle of fake fur, blue eyeliner sharp and pointed nearly to her brows. She tried to teach me how to do that once, but I shook too much. Jon looks like he has rich parents, and he does, richer than mine, one’s a lawyer I think and the other has a senior position at the Guardian. He doesn’t sound rich though, there’s an affected edge to his voice, Ts dropped as often as he can. Until he gets really drunk, or really high, or both. Then that clipped BBC English comes out swinging. He’s not there yet though.

“Hey, Alice, how’re ya?”

It seems mocking, but I can’t tell who it’s meant to be mocking.

“I’m okay,” I say.

“Been busy?”

I laugh. “Good one, Jon. You?”

He shrugs. “Been working a lot.”

Yeah, right …

Sasha comes to me and we hug. The fake fur coat she’s wearing is unbelievably soft, I want to just settle into it and sleep for an eternity, but then she breaks the embrace.

“You look pretty!” she says, really meaning it.

“Got any gear?” asks Leon.

“Jesus, that was quick. You didn’t even say hello.”

“Nah,” he says. “You need to have drugs on you to get into the party.”

“Ah, shit, really?” I have a little Ziploc bag of pills back in my makeup box at the flat, but I thought I wouldn’t be doing anything tonight. Shit.

“It’s okay,” says Jon, “I’ve got like, two extra bags of MD and a bag of Ket that I don’t need.” I hesitate. “You don’t have to use, just give it back to me once we’re in, y’know.”

He holds three bags of identical white powder out to me in the palm of his hand, and I take one at random, not knowing if it’s MD or Ket and not caring. He must have already given some to Sasha, and Leon is probably always carrying anyway. Cops never stop him. He’s small, they mistake him for a white girl, they don’t care, why would they? We exchange curt nods, the sort of acknowledgement you do to one another when you are the only trans people in a situation. Maybe there’ll be more of us at the party, I don’t know the crowd, but probably not.

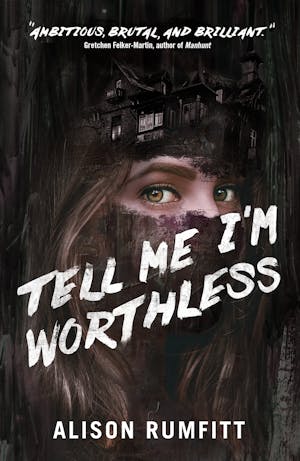

Copyright © 2021 by Alison Rumfitt