1

Albany.

A southern city running on country fuel.

Divided east to west by the Flint River, this corner of southwest Georgia is graced with majestic pecan groves and wildflower carpets buffered by blue skies; a region where flip sides coalesce, modern and antebellum, old growth and new wood. A place of long, deep pain, still refusing forgiveness; and yet propelled by joys and triumphs. In many ways, even in 2012, life here was the same as it was fifty years ago: a patchwork of citizens—from farmers and businesspeople to college students—going about their days as any other, separate and unequal.

Fletcher Dukes lived a few miles south of town in a widening-in-the-road called Putney. His property has been in their family since before he was born, back when a Black man wasn’t likely to own a paltry lot, let alone seven acres.

Fletcher’s single-story brick house sat on three acres. A long driveway shot like a red clay ruler, straight from Sumac Road into Fletcher’s front yard. If you parked a line of cars bumper to bumper, Car #1 would touch his front porch, and Car #10, his mailbox.

His property’s back section faced north and included a four-acre pine forest stretching out eastwardly in an L-shape, and wrapping around a large meadow where two rusting cars and a pickup had become fixtures. Kudzu mushroomed through windshields, and dog fennel hugged flat tires.

It was unseasonably hot for March. Engulfed by diesel fumes, Fletcher paused, his body jiggling to the old tractor’s rhythm. He used a crisp, white handkerchief to wipe sweat from his neck, then swerved in a wide turn, and maneuvered around each vehicle to mow down what was left of weeds.

Tractor parked, he paused in his seat. If he closed his eyes, hot wind blowing through pines could be waves breaking on a beach somewhere. He had time for a shower before picking up his elder sister, Olga, who lived across town, for their weekly grocery run.

A little while later, Fletcher pulled his Ford Fairlane into Piggly Wiggly’s parking lot, grumbling to Olga about a red Volvo wagon hitched to a U-Haul trailer and parked across three spaces.

“Now whoever this is from Michigan ought to park this rig out on the edge and leave these good spaces up front for local folk.”

Olga, who was slowly losing her sight, said, “We got our handicap space no matter what.”

Ordinarily she would have more to say about northern license plates, but as she adjusted to blindness, she had become more and more quiet. Her reticence continued as a pink-faced man joined them, walking toward the front doors.

“Yeah, I seen’er pull in,” the man drawled, “act like she own the place.”

Fletcher chuckled. “Well, I guess they don’t teach ’em how to park up north.

“Whoever she is,” he said to Olga, his hand cupping her elbow, “she can’t be all bad: got Obama/Biden in her windshield.”

As always, they started in produce, Olga pushing, with Fletcher holding both lists, out front guiding. They turned down the liquor aisle, headed for meat, poultry, fish.

Fletcher smelled her perfume first, a scent he knew well but could no longer name; a soft powdery bouquet that instantly made him think of Altovise Benson.

He and Olga walked slowly past a tall woman with short, wavy, salt-and-pepper hair and skin in shades of paper shell pecans. Her head was bowed reading a wine label, revealing smooth, clear skin at the nape of her neck—a spot women in Fletcher’s life call their kitchen. This woman had a birthmark in her kitchen: a perfect strawberry, almost like a tattoo. This, together with her perfume and long beaded earrings, gave Fletcher reason to hurry past, his heart throbbing. He was grateful that Olga wasn’t in a talkative mood.

At checkout, he watched, thinking about Michigan plates. All six of Altovise’s albums were recorded in Detroit.

Olga chatted with her cashier, a former student, as Fletcher split his attention between the aisle and his sister’s hand holding her ATM card.

If only he could glimpse the woman’s hands, he was sure he’d see matching medicine knot tattoos beneath each wrist. Altovise was part Muscogee Creek.

She rounded the corner, pushing her cart away from him. He took a few steps back, needing to see her walk to confirm what he already knew.

“I’ll be damn,” he whispered, his heart lurching.

Like watching a scene in a favorite movie, he smiled at her long strides, slightly slue-foot. He was only four months older but seemed like a relic by comparison. His granddaughters would say Altovise was fierce in her crisp white oversize shirt. Denim legs vanished behind a Coke display and Fletcher flashed on walking hand in hand, her with a giant teddy bear, at Dougherty’s county fair. If Olga only knew how close they both stood at that moment to their very own Altovise.

As they fastened seat belts, Olga said, “Well, that doesn’t happen every day.”

“What you mean?”

“Estée Lauder Youth Dew. I smelled it in the store on somebody. That’s an old-timey perfume, was everywhere in the ’50s and ’60s, but not that much anymore.”

Fletcher stared ahead at Michigan plates, which now took on a completely different meaning.

He couldn’t explain why he didn’t mention Altovise as he drove Olga home. Later, he would look down through the backbone of this day in search of signs he had missed, and he would recognize that red Volvo wagon as the calm before a storm called Altovise Benson—walking around his Piggly Wiggly. After fifty-two years.

* * *

Before dawn, Fletcher’s bedside radio hissed a song buried in static, and he woke from a shallow, restless sleep. Eyes still closed, radio off. Altovise’s face played behind his lids like a beautiful song stuck in his head.

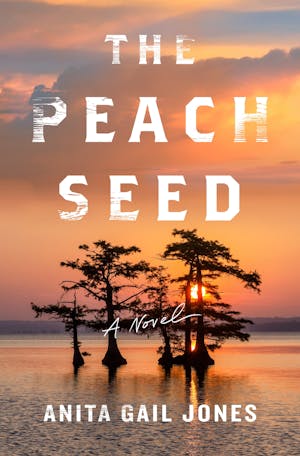

Copyright © 2023 by Anita Gail Jones