ONE

When I was seven, I found a sparkling lying dead on a bench at the edge of the woods which formed the back boundary of our garden, that the groundskeeper had not yet cleared away. With much excitement, I brought it for my mother to see, but by the time I reached her it had mostly collapsed into ash in my hands. Mama exclaimed in distaste and sent me to wash.

Our cook, a tall and gangly woman who nonetheless produced the most amazing soups and soufflés (thus putting the lie to the notion that one cannot trust a slender cook) was the one who showed me the secret of preserving sparklings after death. She kept one on her dresser top, which she brought out for me to see when I arrived in her kitchen, much cast down from the loss of the sparkling and from my mother's chastisement. "However did you keep it?" I asked her, wiping away my tears. "Mine fell all to pieces."

"Vinegar," she said, and that one word set me upon the path that led to where I stand today.

If found soon enough after death, a sparkling (as many of the readers of this volume no doubt know) may be preserved by embalming it in vinegar. I sailed forth into our gardens in determined search, a jar of vinegar crammed into one of my dress pockets so the skirt hung all askew. The first one I found lost its right wing in the process of preservation, but before the week was out I had an intact specimen: a sparkling an inch and a half in length, his scales a deep emerald in color. With the boundless ingenuity of a child, I named him Greenie, and he sits on a shelf in my study to this day, tiny wings outspread.

Sparklings were not the only things I collected in those days. I was forever bringing home other insects and beetles (for back then we classified sparklings as an insect species that simply resembled dragons, which today we know to be untrue), and many other things besides: interesting rocks, discarded bird feathers, fragments of eggshell, bones of all kinds. Mama threw fits until I formed a pact with my maid, that she would not breathe a word of my treasures, and I would give her an extra hour a week during which she could sit down and rest her feet. Thereafter my collections hid in cigar boxes and the like, tucked safely into my closets where my mother would not go.

No doubt some of my inclinations came about because I was the sole daughter in a set of six children. Surrounded as I was by boys, and with our house rather isolated in the countryside of Tamshire, I quite believed that collecting odd things was what children did, regardless of sex. My mother's attempts to educate me otherwise left little mark, I fear. Some of my interest also came from my father, who like any gentleman in those days kept himself moderately informed of developments in all fields: law, theology, economics, natural history, and more.

The remainder of it, I fancy, was inborn curiosity. I would sit in the kitchens (where I was permitted to be, if not encouraged, only because it meant I was not outside getting dirty and ruining my dresses), and ask the cook questions as she stripped a chicken carcass for the soup. "Why do chickens have wishbones?" I asked her one day.

One of the kitchen maids answered me in the fatuous tones of an adult addressing a child. "To make wishes on!" she said brightly, handing me one that had already been dried. "You take one side of it—"

"I know what we do with them," I said impatiently, cutting her off without much tact. "That's not what chickens have them for, though, or surely the chicken would have wished not to end up in the pot for our supper."

"Heavens, child, I don't know what they grow them for," the cook said. "But you find them in all kinds of birds—chickens, turkeys, geese, pigeons, and the like."

The notion that all birds should share this feature was intriguing, something I had never before considered. My curiosity soon drove me to an act which I blush to think upon today, not for the act itself (as I have done similar things many times since then, if in a more meticulous and scholarly fashion), but for the surreptitious and naive manner in which I carried it out.

In my wanderings one day, I found a dove which had fallen dead under a hedgerow. I immediately remembered what the cook had said, that all birds had wishbones. She had not named doves in her list, but doves were birds, were they not? Perhaps I might learn what they were for, as I could not learn when I watched the footman carve up a goose at the dinner table.

I took the dove's body and hid it behind the hayrick next to the barn, then stole inside and pinched a penknife from Andrew, the brother immediately senior to me, without him knowing. Once outside again, I settled down to my study of the dove.

I was organized, if not perfectly sensible, in my approach to the work. I had seen the maids plucking birds for the cook, so I understood that the first step was to remove the feathers—a task which proved harder than I had expected, and appallingly messy. It did afford me a chance, though, to see how the shaft of the feather fitted into its follicle (a word I did not know at the time), and the different kinds of feathers.

When the bird was more or less naked, I spent some time moving its wings and feet about, seeing how they operated—and, in truth, steeling myself for what I had determined to do next. Eventually curiosity won out over squeamishness, and I took my brother's penknife, set it against the skin of the bird's belly, and cut.

The smell was tremendous—in retrospect, I'm sure I perforated the bowel—but my fascination held. I examined the gobbets of flesh that came out, unsure what most of them were, for to me livers and kidneys were things I had only ever seen on a supper plate. I recognized the intestines, however, and made a judicious guess at the lungs and heart. Squeamishness overcome, I continued my work, peeling back the skin, prying away muscles, seeing how it all connected. I uncovered the bones, one by one, marveling at the delicacy of the wings, the wide keel of the sternum.

I had just discovered the wishbone when I heard a shout behind me, and turned to see a stableboy staring at me in horror.

While he bolted off, I began frantically trying to cover my mess, dragging hay over the dismembered body of the dove, but so distressed was I that the main result was to make myself look even worse than before. By the time Mama arrived on the scene, I was covered in blood and bits of dove-flesh, feathers and hay, and more than a few tears.

I will not tax my readers with a detailed description of the treatment I received at that point; the more adventurous among you have no doubt experienced similar chastisement after your own escapades. In the end I found myself in my father's study, standing clean and shamefaced on his Akhian carpet.

"Isabella," he said, his voice forbidding, "what possessed you to do such a thing?"

Out it all came, in a flood of words, about the dove I had found (I assured him, over and over again, that it had been dead when I came upon it, that I most certainly had not killed it), and about my curiosity regarding the wishbone—on and on I went, until Papa came forward and knelt before me, putting one hand on my shoulder and stopping me at last.

"You wanted to know how it worked?" he asked.

I nodded, not trusting myself to speak again lest the flood pick up where it had left off.

He sighed. "Your behaviour was not appropriate for a young lady. Do you understand that?" I nodded. "Let's make certain you remember it, then." With one hand he turned me about, and with the other he administered three brisk smacks to my bottom that started the tears afresh. When I had myself under control once more, I found that he had left me to compose myself and gone to the wall of his study. The shelves there were lined with books, some, I fancied, weighing as much as I did myself. (This was pure fancy, of course; the weightiest book in my library now, my own De draconum varietatibus, weighs a mere ten pounds.)

The volume he took down was much lighter, if rather thicker than one would normally give to a seven-year-old child. He pressed it into my hands, saying, "Your lady mother would not be happy to see you with this, I imagine, but I had rather you learn it from a book than from experimentation. Run along, now, and don't show that to her."

I curtseyed and fled.

Like Greenie, that book still sits on my shelf. My father had given me Gotherham's Avian Anatomy, and though our understanding of the subject has improved a great deal since Gotherham's day, it was a good introduction for me at the time. The text was only half comprehensible to me, but I devoured the half I could understand and contemplated the rest in fascinated perplexity. Best of all were the diagrams, thin, meticulous drawings of avian skeletons and musculature. From this book I learned that the function of the wishbone (or, more properly, the furcula) is to strengthen the thoracic skeleton of birds and provide attachment points for wing muscles.

It seemed so simple, so obvious: all birds had wishbones, because all birds flew. (At the time I was not aware of ostriches, and neither was Gotherham.) Hardly a brilliant conclusion in the field of natural history, but to me it was brilliant indeed, and opened up a world I had never considered before: a world in which one could observe patterns and their circumstances, and from these derive information not obvious to the unaided eye.

Wings, truly, were my first obsession. I did not much discriminate in those days as to whether the wings in question belonged to a dove or a sparkling or a butterfly; the point was that these beings flew, and for that I adored them. I might mention, however, that although Mr. Gotherham's text concerns itself with birds, he does make the occasional, tantalizing reference to analogous structures or behaviours in dragonkind. Since (as I have said before) sparklings were then classed as a variety of insect, this might count as my first introduction to the wonder of dragons.

* * *

I should speak at least in passing of my family, for without them I would not have become the woman I am today.

Of my mother I expect you have some sense already; she was an upright and proper woman of her class, and did the best she could to teach me ladylike ways, but no one can achieve the impossible. Any faults in my character must not be laid at her feet. As for my father, his business interests kept him often from home, and so to me he was a more distant figure, and perhaps more tolerant because of it; he had the luxury of seeing my misbehaviours as charming quirks of his daughter's nature, while my mother faced the messes and ruined clothing those quirks produced. I looked upon him as one might upon a minor pagan god, earnestly desiring his goodwill, but never quite certain how to propitiate him.

Where siblings are concerned, I was the fourth in a set of six children, and, as I have said, the only daughter. Most of my brothers, while of personal significance to me, will not feature much in this tale; their lives have not been much intertwined with my career.

The exception is Andrew, whom I have already mentioned; he is the one from whom I pinched the penknife. He, more than any, was my earnest partner in all the things of which my mother despaired. When Andrew heard of my bloody endeavours behind the hayrick, he was impressed as only an eight-year-old boy can be, and insisted I keep the knife as a trophy of my deeds. That, I no longer have; it deserves a place of honor alongside Greenie and Gotherham, but I lost it in the swamps of Mouleen. Not before it saved my life, however, cutting me free of the vines in which my Labane captors had bound me, and so I am forever grateful to Andrew for the gift.

I am also grateful for his assistance during our childhood years, exercising a boy's privileges on my behalf. When our father was out of town, Andrew would borrow books out of his study for my use. Texts I myself would never have been permitted thus found their way into my room, where I hid them between the mattresses and behind my wardrobe. My new maid had too great a terror of being found off her feet to agree to the old deal, but she was amenable to sweets, and so we settled on a new arrangement, and I read long into the night on more than one occasion.

The books he took on my behalf, of course, were nearly all of natural history. My horizons expanded from their winged beginnings to creatures of all kinds: mammals and fish, insects and reptiles, plants of a hundred sorts, for in those days our knowledge was still general enough that one person might be expected to familiarize himself (or in my case, herself ) with the entire field.

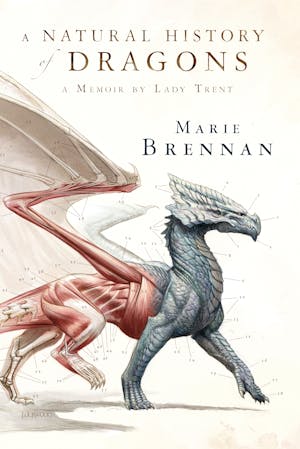

Some of the books mentioned dragons. They never did so in more than passing asides, brief paragraphs that did little more than develop my appetite for information. In several places, however, I came across references to a particular work: Sir Richard Edgeworth's A Natural History of Dragons. Carrigdon & Rudge were soon to be reprinting it, as I learned from their autumn catalogue; I risked a great deal by sneaking into my father's study so as to leave that pamphlet open to the page announcing the reprint. It described A Natural History of Dragons as "the most indispensable reference on dragonkind available in our tongue"; surely that would be enough to entice my father's eye.

My gamble paid off, for it was in the next delivery of books we received. I could not have it right away—Andrew would not borrow anything our father had yet to read—and I nearly went mad with waiting. Early in winter, though, Andrew passed me the book in a corridor, saying, "He finished it yesterday. Don't let anyone see you with it."

I was on my way to the parlor for my weekly lesson on the pianoforte, and if I went back up to my room I would be late. Instead I hurried onward, and concealed the book under a cushion mere heartbeats before my teacher entered. I gave him my best curtsy, and thereafter struggled mightily not to look toward the divan, from which I could feel the unread book taunting me. (I would say my playing suffered from the distraction, but it is difficult for something so dire to grow worse. Although I appreciate music, to this day I could not carry a tune if you tied it around my wrist for safekeeping.)

Once I escaped from my lesson, I began in on the book straightaway, and hardly paused except to hide it when necessary. I imagine it is not so well-known today as it was then, having been supplanted by other, more complete works, so it may be difficult for my readers to imagine how wondrous it seemed to me at the time. Edgeworth's identifying criteria for "true dragons" were a useful starting point for many of us, and his listing of qualifying species is all the more impressive for having been assembled through correspondence with missionaries and traders, rather than through firsthand observation. He also addressed the issue of "lesser dragonkind," namely, those creatures such as wyverns which failed one criterion or another, yet appeared (by the theories of the period) to be branches of the same family tree.

The influence this book had upon me may be expressed by saying that I read it straight through four times, for once was certainly not enough. Just as some girl-children of that age go mad for horses and equestrian pursuits, so did I become dragon-mad. That phrase described me well, for it led not only to the premier focus of my adult life (which has included more than a few actions here and there that might be deemed deranged), but more directly to the action I engaged in shortly after my fourteenth birthday.

Copyright © 2013 by Bryn Neuenschwander