THE CHRISTMAS SHOES (Chapter One)December 1985

We did not dare to breathe a prayer,

Or give our anguish scope.

Something was dead within each of us,

And what was dead was Hope.

—Oscar Wilde

The first big snowstorm of the winter of 1985 fell on Thanksgiving. After that, another massive storm seemed to enter the area every few weeks and drop inches, or even a foot, blanketing the landscape and making the town look like a Christmas card, long before the holiday arrived.

Schools were closed more times that winter than in the previous five years combined. Nearly every week, Doris Patterson finalized the lesson plan for her second-grade class, only to have to change it entirely due to yet another snow day.

After twenty-nine years of teaching, Doris was accustomed to the unexpected. Where some saw chaos, she saw opportunity. When the principal announced an early dismissal over the PA system, Doris tried to think up a fun, new assignment for her students, to accompany the traditional spelling and math homework. Assignments like What are the flowers thinking beneath the snow? or When do birds make reservations to fly south? Though simple assignments, she'd seen them stir her students' imaginations, creating wonderful memories for her scrapbook.

In the last couple of years, Doris had considered retiring but, for whatever reason, had always felt she wasn't ready. Until now. She'd recently informed the principal that this would be her last school year. Her husband had retired four years earlier from the post office. He was anxious to hit the wide-open roads with her in a brand-new RV he'd purchased, with "Herb and Doris" airbrushed in blue and pink on the spare-tire cover. Maybe it was all the snow there had been that year, but warm winters in the Southwest had begun to sound good to her.

Doris never showed favoritism outwardly, but every year there was one child in her classroom who captured her heart. In 1985 that child was Nathan Andrews. Nathan was quiet and introspective. He had sandy hair, huge blue eyes, and a shy smile. Doris noticed that his gentle nature was lacking the spark she'd seen in his previous two years at the school. While other students interrupted her with "Um, Mrs. Patterson, Charity just sneezed on my head" or "Hey, Mrs. Patterson, Jacob just hit me with a spitball," Nathan made his way to her desk without calling attention to himself and whispered, "Excuse me, Mrs. Patterson." He'd then wait patiently until she turned to him. Compared with the boisterous natures of the twenty-five other eight-year-olds in her class, Nathan's measured, serious disposition was, almost in a sad way, beyond his years.

Some of her colleagues maintained that children from poorer homes were harder to teach, had more disciplinary problems, and were generally mouthier than those students who came from middle- to upper-class homes. Doris disagreed. She knew Nathan's family could be considered lower income. Mr. Andrews worked at a local auto-repair shop and, people said, could barely make ends meet. Yet in all her years of teaching, Nathan was one of the most polite children she'd ever met. Doris had learned that it wasn't the size or cost of a home that created kind, well-adjusted children, but the love and attention that filled that home.

Nathan's mother had often volunteered at the school in the early fall. She had helped out in Doris's classroom, cutting out shapes and numbers for a math lesson, sounding out words for a student struggling with phonics, or stapling paper flowers and trees on the bulletin board. Nathan would beam with pride at the sight of his mother. But Doris hadn't seen Maggie Andrews in many weeks.

One day her husband, Jack, had come to school to tell Doris that his wife was seriously ill. Maggie Andrews had cancer, and the prognosis wasn't good. No wonder Nathan often seemed distracted. He was not old enough to fully understand the situation and probably didn't know that his mother was dying. But some days Doris could see it in the boy's eyes, a terrible sadness she recognized.

Her own mother had died of cancer when Doris was only twenty, and that single event had indelibly changed her. Her heart broke for the little boy as she watched him erase a hole into his paper, smoothing the tear with the back of his small hand as he continued with his work. She'd never had a student in her class who had lost a parent, and she found herself at a loss for words or actions. Somehow the gentle hug or extra playtime she'd given over the years to children who had lost a precious pet or extended family member seemed inadequate, even inappropriate. She still remembered that after her mother's death, she had wished that people would say nothing at all, rather than the trite, though well-meaning words they'd offered in sympathy. Sometimes being quiet is the greatest gift you can give someone, Doris thought, as she watched the boy sharpen his pencil, something terribly heartbreaking in the way he struggled to turn the handle. She whispered a silent prayer for God to draw near and wrap the little boy in His arms.

I slammed the phone down in my office. For the umpteenth time, I had tried to make a call, only to hear a busy signal in my ear. The day was short on hours, and I was feeling even shorter on patience.

"Would somebody tell me how these new phones are supposed to work?" I shouted out my office door to my secretary.

Gwen Sturdivant, my assistant for the past ten years, hurried in to help me.

"First, make sure you select a line that isn't lit up," she explained.

"I know that, Gwen," I said, exasperated. "I'm thirty-eight years old. I'm familiar with the general uses of a telephone. I want to know why I hear that stupid busy signal every time I make a call."

"Once you dial, you need to wait for the tone and then punch in one of these codes for the client you're billing to." Gwen calmly demonstrated.

When I had started with the firm, the phone bill, along with the electric bill and office expenses, had been paid from the firm's general receipts. Now everything—the fax machine, the photocopier, the office phones—all had a code. As soon as someone could figure out how to program it, my pager would have a code too. Ordinary tasks like dialing the phone had been made more frustrating so the firm could bill our clients right down to the penny.

"Just get Doug Crenshaw on the phone for me!" I groaned.

I had been at Mathers, Williams & Hurst for thirteen years. Like many young attorneys, I had walked in the door a bright-eyed, naively optimistic law-school graduate. We were a small firm at the time, sixteen lawyers, but the location was perfect—only a few miles from my mother's home. My father had died of a heart attack five years earlier, and I wanted to move closer to my mother so I could keep an eye on her, in case she needed anything. My wife Kate's family lived only three hours away, so she couldn't have been more pleased when I took the job.

I spent the first day at MW&H in conference, a conference that had lasted thirteen years: conferences with clients, conferences with other associates, conferences with the firm's partners, conferences with secretaries, conferences with paralegals, conferences at lunch, conferences over the phone. The visions of wowing a courtroom with my verbal prowess faded as the firm's partners shifted many of their bankruptcy cases onto my desk. I had not minded the work at first. It was challenging and fun in the beginning, helping owners of small businesses and corporations liquidate their assets, seeing so many zeroes on a page reduced to one lone goose egg. Somehow my position within the firm as "the associate who helped with bankruptcy cases" changed over the years to "our bankruptcy associate." After I got over my initial disappointment and accepted that my dream of becoming a hotshot courtroom brawler was not going to play out (the bankruptcy cases that made it as far as the courtroom were invariably simple presentations of fact, never the in-your-face litigating tours de force I'd always dreamed of performing), I buried myself in the bankruptcy files to impress the partners. My position within the firm established, I concentrated on every young law student's goal: to become partner in just seven years.

I found that once I put my mind to a task and worked at it diligently, things came together as I had planned. Even with my wife, this seemed true.

I met Kate Abbott during my last year of law school. From the moment I saw her, I was smitten. She had recently moved into the neighborhood where I was sharing a small apartment with five roommates. My parents had paid for my books and tuition, on the condition that I support myself by taking on odd jobs to pay for food, rent, clothes, and whatever car I could afford. Meals in those days consisted of macaroni and cheese, Ramen noodles, and the rare special of Five Burgers for a Buck at the local Burger Castle. I owned one suit that my parents had bought me for my college graduation, three pairs of jeans, several ratty sweatshirts, two button-down shirts, a pair of loafers with a hole in the sole, and a pair of old running shoes. I would have felt my wardrobe was pathetic had not my roommates' clothes looked exactly the same.

I first saw Kate unloading boxes and secondhand furniture from the back of a U-Haul van. I set out to meet her, and then, once I met her, I set out to marry her. She was raven-haired and lovely. A certain melody filled the air when she laughed. We married a week after I finished law school.

Like most new law graduates, I was poor and saddled with debt. Kate continued her work in the marketing department of a small local hospital while I looked for a job. Though her salary was paltry, it paid the rent on our tiny one-bedroom apartment and put gas and the occasional spark plug in our beat up Plymouth Champ. We both knew we would struggle for a few years but that once my career took off, we'd live comfortably.

With my job secure at Mathers, Williams & Hurst, the money started rolling in. Kate suggested that we stay on in our apartment, or maybe move to a small condo for a few years, so we could sock away savings for our future. I disagreed; we couldn't entertain my colleagues in cramped quarters decorated with hand-me-down furniture from our parents or the Goodwill store. Like it or not, part of being an effective attorney is looking the part, and I felt that extended to our home.

We bought a large brick house in a respectable neighborhood and filled it with furniture. My old wardrobe was quickly replaced with freshly starched Polo shirts, Hart Schaffner and Marx suits, and Johnston and Murphy shoes. I considered the Plymouth Champ beneath Kate's status and sold it for $500, buying her what she called a "no-personality" used Volvo sedan, to sit beside my new BMW in our new two-car garage.

Both cars, like the home and the furniture, were financed. Kate had grown up in a home where nothing was purchased on credit. Her parents hadn't even owned a credit card until she was in college, and the card was used only for absolute necessities; the balance was paid off at the beginning of every month. As hard as she tried, Kate couldn't see as crucial to our well-being a Carver CD player, tape deck, amp, and preamp, a Thorens turntable, B&W speakers, hi-fi Mitsubishi VCR, or 27-inch Proton monitor. But I always prevailed. Each item was the best our money could buy, and I justified the purchases by reasoning "We have the money, and we're not tied down with kids yet. Let's have some fun with it while we can." When Kate complained that the house was too large, as she often did, I reminded her that we would need extra room after the children were born.

We were just about to celebrate our fifth wedding anniversary when Kate got pregnant. I had imagined that we would wait a couple more years to start a family. A few months into the pregnancy, I wanted to put the house on the market to move to a neighborhood with better schools.

"Robert, the baby won't be in school for years," Kate protested.

"Once the baby comes, we'll have twice as much stuff, and the move will be twice the headache," I said. "This is the right time."

We put our place on the market and began the search for a new house. Several of my colleagues lived in what was called the Adams Hill section of town, an older neighborhood that boasted of even older money. The area was named for Thomas Adams, one of the area's founding residents, who claimed to be related to President John Quincy Adams, though none of the locals had ever bothered to research his genealogy.

People of affluence and influence have lived in Adams Hill since before the turn of the twentieth century. The streets were lined with red maple and giant oak trees older than the oldest resident of Adams Hill. The lawns were professionally manicured; the shrubs were trimmed and clipped. The well-kept homes were all built of brick, wood, and stone, with not a panel of vinyl siding in sight. Great Victorian homes with enormous wraparound porches nestled among the oak trees, next to brick colonials with huge antebellum columns out front. Each home had a story. Many even had placards positioned next to the front door stating the year the home was built and any other information deemed worthy of sharing with those fortunate enough to ring the doorbell. Finding a residence that was actually for sale, as opposed to handed down from one generation to the next, was nearly impossible.

When the new listing popped up on our real-estate agent's computer, she couldn't reach for the phone quickly enough to call us. My palms began to sweat as I anticipated walking through what could be my dream home. Even Kate couldn't suppress a smile when the Realtor led us into the drive. The front was gray stone and yellow wood, with a beautiful double-tiered wraparound deck. It was a big house and, of course, that meant a big mortgage, but I wanted Kate to have lots of space to create a lovely home for our family. A home, like my mother's, that would come alive at Christmas with a roaring fire and a tall, sparkling tree.

Though the firm was pleased with my work, there were times I wished I'd opened a private practice, the way so many of my law-school buddies did, hiring two or three associates, their names painted in gold letters on doors (Gerald Greenlaw & Associates), on lawn signs, (Curtis Howard & Associates), or on parking-garage walls (Thomas Michelson & Associates). Instead of working eighty hours a week for someone else, I could have been working for myself—Robert Layton & Associates. It was too late to start over now, however, and our brand-new mortgage confirmed it. What I lost in freedom, I made up for in the security of working for a larger firm.

In the seventh year of my service with them, the partners at Mathers, Williams & Hurst unanimously made me a partner. They called me into the conference room, each partner seated in a leather chair at the cherry table that ran the length of the room. They made their announcement, clapped me on the back with congratulations, promised to get together with the wives very soon, and went back to work. The celebration lasted all of two minutes. I sat alone at the table as they filed out, thinking that this moment hadn't lived up to my expectations. Then I slowly walked back to my office, shut the door, and began sifting through the bankruptcy files Gwen had placed on my desk that morning.

I was so busy for the rest of the day that I completely forgot to call Kate and tell her the news. By the time I pulled into the driveway, the house was dark. Kate, in her seventh month of her second pregnancy, was no doubt exhausted chasing after our two-year-old daughter, Hannah. Like the first, this pregnancy was unplanned. To be honest, I had wanted to wait a few years before we had another child. I was so busy, I hardly had time to see Hannah. I worried that I would not be able to be a proper father to baby number two…and if I was, would it be at Hannah's expense?

Kate, of course, was ecstatic. Hannah had brought a joy into her life that I hadn't seen in a long time, and I knew this baby would do the same. Kate loved being a mother. I can admit that she was much more adept at being a mom than I was at being a dad. I had to work to understand what my daughter was saying, whereas Kate could carry on a full conversation with her without missing a beat.

I pushed open Hannah's door, her Winnie the Pooh night-light smiling at me from across the room. I walked softly to her bed. She looked so much like Kate when she was asleep, but when her eyes were open they blazed, as my mother said, with the same fire she'd seen in mine when I was young. I kissed her on the head, picking Bobo, her one-eyed stuffed bunny, off the floor, and put him back under the blankets before leaving the room. Peeking into our bedroom I saw that Kate was asleep. I heard her slight snoring, which had gotten louder as her pregnancy progressed, one of the side effects, as was fatigue, but even so, during the first pregnancy, she used to wait up for me. I closed the door and made my way down the stairs into the kitchen for something to eat.

In the refrigerator I found a cold, wrapped hamburger patty and some macaroni and cheese. As I put the plate in the microwave, I wondered when we would ever be able to eat food again that didn't come in colors, shapes, numbers, or that wasn't smothered in processed cheese. I'd come too far to be eating macaroni again, the way I did when I was single. Finding a hamburger bun or condiments was too much hassle, so when my food popped and splattered in the microwave, I took it out and let it cool as I poured myself a glass of milk. The recessed lighting I had had installed under the kitchen cabinets burned dimly as I sat down at the kitchen counter and toasted myself, "To Partner Layton," I said, raising the glass. And as the clock struck ten, I ate my rubbery hamburger and my macaroni and cheese, alone.

One night, shortly before Christmas, I came home to find the house dark, save a blue light glowing in the livingroom window. Hannah, now eight, and her six-year-old sister, Lily, were long asleep. It was the third time that week I'd gotten home late, though the holiday season was always busy. Everyone was putting in eighty-hour weeks, and I couldn't expect special treatment. To top it off, Gwen had been crying in my office that morning. The long hours were "ripping her apart" and "wearing her down." She threatened to quit, as she had for the last eight holiday seasons, so I gave her the rest of the day off, with pay, knowing she would be back the next morning good as new and telling me how relieved she was to have gotten her shopping done.

I put the Mercedes in the garage, dropped my briefcase heavily on the dining-room table, and went to the living room, expecting to find Kate asleep in front of an I Love Lucy rerun. Instead, she was awake.

"Girls asleep?" I asked, flipping through the stack of bills.

"Yep."

"Everybody have a good day?" I asked, uninterested.

"Yeah. You?"

"Busy. You know. I let Gwen have the day off. Had her holiday cry," I said as I walked into the kitchen. I opened the refrigerator door and began my nightly rummaging for dinner leftovers.

Kate moved to the dining-room table and watched for a long time before she finally spoke.

"I'm tired, Robert," she said evenly.

"Go to bed. You didn't have to wait up for me," I told her halfheartedly.

"No, Robert. I'm tired of this. Of us."

I stood frozen, my head still in the refrigerator. In my heart, I'd known the marriage had been over for nearly a year, but I had never imagined either one of us would have the courage to bring it up. I should have known it would be Kate. She'd always been the stronger one. The year before she had accused me of having an affair. I wasn't. She never believed me, but there had never been another woman. Frankly, there'd never been enough time for Kate, let alone another woman. Some nights, I knew, I worked late because it was the one thing I knew I could do for my family, one concrete step I could take to make sure that they had the things that they needed, that the girls' college tuitions were taken care of, that there was a roof over their heads. Some nights I worked late because I didn't know what else to do, and because I didn't want to go home and face the fact that we were in trouble.

I dragged some sort of casserole from the top shelf of the refrigerator and silently pulled a plate down from the cabinet. I couldn't seem to find the words I wanted to say.

"I'm sorry, Robert, but I just can't do this anymore," Kate continued. "I can't go on pretending that everything's all right. It's not all right. It hasn't been for some time. Living under the same roof doesn't mean we're living together. I need more than this."

I stared blankly at the casserole in front of me. She needs more, I thought to myself. Well, I don't have any more. I have given everything, I reasoned. I can't work harder. I can't do more. But I didn't say any of that.

"Let's face it, you left this family a long time ago. We'll stay together through the holidays," Kate explained unemotionally. This all seemed too easy for her, almost as if she'd rehearsed it several times.

"I don't want to ruin my family's Christmas or your mother's, and it'd absolutely kill the girls if we split up right now. But as soon as the holidays are over, you'll have to find another place to live."

There. It was over. She paused briefly to see if I would respond in any way, but, as expected, I didn't, so she softly wandered back upstairs and closed the bedroom door.

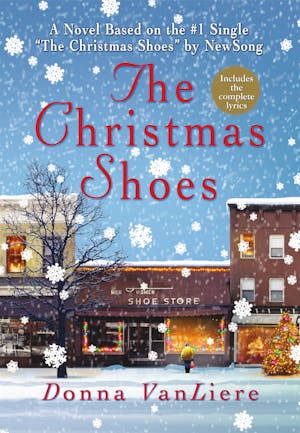

THE CHRISTMAS SHOES Copyright © 2001 by Donna VanLiere.