EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 1

HOW TO BEGIN: Part 1

"No writer would ever betray his secret life, it would be like standing naked in public."--Patricia Highsmith 9/3/40

AN ORDINARY DAY

On 16 November, 1973, a damp, coldish, breaking day in the tiny French village of Moncourt, France, Patricia Highsmith, a fifty-two year old American writer living an apparently quiet life beside a branch of the Loing Canal, lit up another Gauloise jaune, tightened her grip on her favorite Parker fountain pen, hunched her shoulders over her roll-top desk -- her oddly-jointed arms and enormous hands were long enough to reach the back of the roll while she was still seated –- and jotted down in her writer's notebook a short list of helpful activites "which small children" might do "around the house."

It's a casual little list, the kind of list Pat liked to make when she was emptying out the back pockets of her mind, and it has the tossed-off quality of an afterthought. But as any careful reader of Highsmith knows, the time to pay special attention to her is when she seems to be lounging, negligent, or (God forbid) mildly relaxed. There is a beast crouched in every "unconcerned" corner of her writing mind and, sure enough, it springs out at us in her list's discomfiting title. "Little Crimes for Little Tots," she called it. And then for good measure she added a subtitle: "Things around the house which small children Can do..."

Pat had recently filled in another little list –- it was for the comics historian Jerry Bails back in the U.S. –- with some diversionary information about her work on the crime-busting comic book adventures of Black Terror and Sgt. Bill King, so perhaps she was still counting up the ways in which small children could be slyly associated with crime. In her last writer's journal, penned from the same perch in semi-suburban France, she had also spared a few thoughts for children. One of them was a simple calculation. She reckoned that "one blow in anger [would] kill, probably, a child from aged two to eight. . ." and that "Those over eight would take two blows to kill." The murderer she imagined completing this deed was none other than herself; the circumstance driving her to it was a simple one:

"One situation – maybe one alone – could drive me to murder: family life, togetherness."

So, difficult as it might be to imagine Pat Highsmith dipping her pen into child's play, her private writings tell us that she sometimes liked to run her mind over the more outré problems of dealing with the young. And not only because her feelings for them wavered between a clinical interest in their upbringing (she made constant inquiries about the children of friends) and a violent rejection of their actual presence (she couldn't bear the sounds children made when they were enjoying themselves).

Like her feisty, maternal grandmother Willie Mae Stewart Coates, who used to send suggestions for improving the United States to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (and got handwritten answers back from the White House), Pat kept a drawerful of unconventional ideas for social engineering just itching to be implemented. Her notebooks are enlivened by large plans for small people, most of them modelleled on some harsh outcropping of her own rocky past. Each one adds a new terror to the study of child development.

One of her plans for youth –- just a sample -- seems to be a barely-suppressed rehearsal of the wrench in 1927 in her own childhood when she was taken from her grandmother's care in the family-owned boarding house in Fort Worth, Texas all the way across the United States to her mother's new marriage in a cramped apartment in the upper reaches of the West Side of Manhattan. Pat's idea for child-improvement (it migrated from a serious entry in her 1966 notebook to the mind of the mentally unstable protagonist in her 1977 novel, Edith's Diary) was to send very young children to live in places far across the world --"Orphanages could be exploited for willing recruits!" she enthused, alight with her own special brand of practicality -- so that they could serve their country as "junior members of the Peace Corps."

Like a tissue-culture excised from the skin of her thoughts, her odd, off-hand little list of 16 November, 1973 (written in her house in a village so small that a visit to the Post Office lumbered her with unwanted attention) turns out to be a useful entrée into the mind, the matter, and the mise-en-scène of the talented Miss Highsmith. Among its other revelations, the list makes recommendations for people (small ones) whose lives parallel her own: people who are fragile enough to be confined to their homes, free enough to be without apparent parental supervision, and angry enough to be preoccupied with murder.

Here is her list.

"16/11/73 Little Crimes for Little Tots. Things around the house – which small children can do, such as:

1) Tying string across top of stairs so adults will trip.

2) Replacing roller skate on stairs, once mother has removed it.

3) Setting careful fires, so that someone else will get the blame if possible.

4) Rearranging pills in medicine cabinets; sleeping pills into aspirin bottle. Pink laxative pills into antibiotic bottle which is kept in fridge.

5) Rat powder or flea powder into flour jar in kitchen.

6) Saw through supports of attic trap door, so that anyone walking on closed trap will fall through to stairs.

7) In summer: fix magnifying glass to focus on dry leaves, or preferably oily rags somewhere. Fire may be attributed to spontaneous combustion.

8) Investigate anti-mildew products in gardening shed. Colorless poison added to gin bottle."

A small thing but very much her own, this piece of ephemera, like almost everything Pat turned her hand to, has murder on its mind, centers itself around a house and its close environs, mentions a mother in a cameo role, and is highly practical in a thoroughly subversive way.

Written in the flat, dragging, uninflected style of her middle years, it leaves no particular sense that she meant it as a joke, but she must have…mustn't she? The real beast in Highsmith's writing has always been the double-headed dragon of ambiguity. And the dragon often appears with its second head tucked under its foreclaw and its cue-cards –- the ones it should be flashing at us to help us with our responses – - concealed somewhere beneath its scales. Is Pat serious? Or is she something else?

She is serious and she is also something else.

All her life, Pat Highsmith was drawn to list-making. She loved lists and she loved them all the more because nothing could be less representative of her chaotic, raging interior than a nice, organizing little list. Like much of what she wrote, this particular list makes use of the materials at hand: no need, children, to look further than Mother's's medecine cabinet or Father's garden shed for the means to murder your parents. Many children in Highsmith fictions, if they are physically able, murder a family member. In 1975 she would devote an entire collection of short stories, The Animal Lovers Book of Beastly Murder, to pets who dispatch their abusive human "parents" straight to Hell.

Nor did Pat herself usually look further than her immediate environment for props to implement her artistic motives. (And when she did, she got into artistic trouble.) Everything around her was there to be used –- and methodically so –- even in murder. She fed the odd bits of her gardens, her love life, the carpenter ants in her attic, her old manuscripts, her understanding of the street-plan of New York and the transvestite bars of Berlin into the furnace of her imagination – and then let the fires do their work.

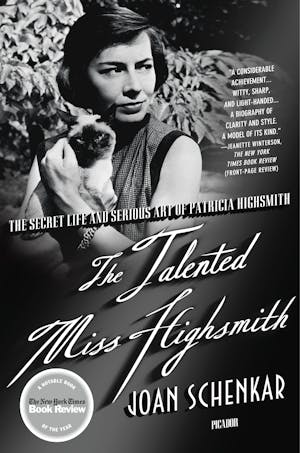

Excerpted from The Talented Miss Highsmith by Joan Schenkar.

Copyright © 2009 by Joan Schenkar.

Published in December 2009 by St. Martin's Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.