Book details

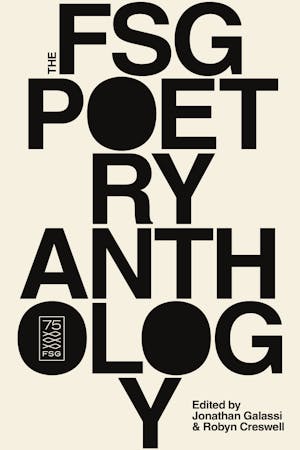

The FSG Poetry Anthology

The FSG Poetry Anthology

$40.00

About This Book

Book Details

To honor FSG's 75th anniversary, here is a unique anthology celebrating the riches and variety of its poetry list—past, present, and future

Poetry has been at the heart of Farrar, Straus and Giroux's identity ever since Robert Giroux joined the fledgling company in the mid-1950s, soon bringing T. S. Eliot, John Berryman, Robert Lowell, and Elizabeth Bishop onto the list. These extraordinary poets and their successors have been essential in helping define FSG as a publishing house with a unique place in American letters.

The FSG Poetry Anthology includes work by almost all of the more than one hundred twenty-five poets whom FSG has published in its seventy-five-year history. Giroux's first generation was augmented by a group of international figures (and Nobel laureates), including Pablo Neruda, Nelly Sachs, Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, and Joseph Brodsky. Over time the list expanded to includes poets as diverse as Yehuda Amichai, John Ashbery, Frank Bidart, Louise Glück, Thom Gunn, Ted Hughes, Yusef Komunyakaa, Mina Loy, Marianne Moore, Paul Muldoon, Les Murray, Grace Paley, Carl Phillips, Gjertrud Schnackenberg, James Schuyler, C. K. Williams, Charles Wright, James Wright, and Adam Zagajewski.

Today, Henri Cole, francine j. harris, Ishion Hutchinson, Maureen N. McLane, Ange Mlinko, Valzhyna Mort, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, and Frederick Seidel are among the poets who are continuing FSG's tradition as a discoverer and promoter of the most vital and distinguished contemporary voices.

This anthology is a wide-ranging showcase of some of the best poems published in America over the past three generations. It is also a sounding of poetry's present and future.

Imprint Publisher

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

ISBN

9780374159115

In The News

"This handsomely designed volume . . . draws on the publisher’s storied history of printing the world’s finest poets, including Marianne Moore, T.S. Eliot, Yusef Komunyakaa and Louise Glück. . . . The poems — drawn from more than 100 writers — run in chronological order, but there’s nothing textbooky about the elegant presentation." —Ron Charles, The Washington Post