1

Mrs. Sargent’s Party

During the winter of 1868–69, a woman with the grand-sounding if socially unfamiliar name of Mrs. Fitzwilliam Sargent, of Philadelphia, hosted dinners at a small, many-windowed house atop the Spanish Steps in Rome. The mistress of the house hadn’t in fact seen Philadelphia for more than fourteen years. Pleasant, imperious, plump, and just over forty, she readily confessed that she liked Rome better than her own native city, liked living next door to the white, two-towered church of Trinità dei Monti, with is views out over the ancient city of Rome. She also admitted to being a watercolorist. Her love for art as well as the Eternal City had prompted her boldness in inviting some of the leading American painters and sculptors in Rome to her house.

Arriving for Mrs. Sargent’s party in horse cabs and the rakish hired carriages known as vetture di rimessa, this parade of theatrical goatees, capes, and walking sticks might have intimidated a lesser woman. But Mrs. Sargent, openhearted if not exactly worldly, remained undaunted. As family friend Vernon Lee understood her, she was ambitious but almost childishly immune to snobbery, “bubbling with sympathies and the need for sympathy,” full of “unquenchable youthfulness and joie de vivre.” She loved the grand and curious in art—anything colorful, really, attracted her—in her household furnishings no less than her illustrious guests. Her artistic drawing room featured a pair of conspicuous if strangely contrasting marble busts: George Washington, the father of his country, and the Egyptian goddess Isis, the mother of hers.

In many ways, these two sculptures neatly embodied Mary Newbold Singer Sargent’s paradoxes. She was a loyal American who still did everything in her power to cling to Europe. She was also a devoted wife and mother of three children who hadn’t, according to nineteenth-century imperatives of domestic virtue and wifely sacrifice, confined herself to some neat Philadelphia row house for her family’s sake.

On the contrary, Mary Sargent used her small private income to channel what a later friend would call a “locomotive disposition.” As Vernon Lee understood the matter, Mary Sargent’s wanderlust was “born of innumerable stay-at-home generations; and this unimpaired zest for travel is but the accumulated thwarted longing of all those sedentary lives.” The progressive journalist Ida Minerva Tarbell, confronting the dynamic and transgressive phenomenon of women’s travel in the era, would understand women like Mary Sargent, this locomotive of her family’s mobility, as engaged in a giddy and sometimes guilty “break for freedom” and a “revolt against security.”

Mary Sargent’s husband, Fitzwilliam, a tall, stiff, narrow-backed, rather haunted-looking man, had offered stability. At the beginning of the Sargents’ marriage in 1850, he’d worked as a doctor at the Wills Hospital in Philadelphia, a promising young surgeon. He’d even published, in 1848, a definitive work on wound-dressing, entitled On Bandaging, and Other Operations of Minor Surgery. But his textbook had never seen a sequel. Dr. Sargent had relinquished his hospital position a dozen years before, in 1856, in order to escort his wife around Europe, for her health.

Now he mingled with modish Europeanized types, artists and bohemians, of whom he (politely) disapproved. In his many devout, long-suffering letters to the United States, he aired his disinclination for “the humbug variety of Americans” who aped European ways. At such a party he had little to do but watch the plates of food circulate and make conversation with his wife’s guests about the healthy or unhealthy “air” of assorted European climates. About this present residence in Rome, his main remark was that the streets struck him as dirtier than before. Though a bright and learned man, Dr. Sargent was more interested in attending the American chapel, in stout Protestant defiance of the papal government of the city, than in mixing with sculptors.

The invited artists filtered into the house, discovering that Mrs. Sargent’s small drawing room commanded a striking view, out over the city toward St. Peter’s. That far-off dome glowing in Rome’s handsome winter light stamped the occasion with a certain elegance. Yet that dome also belonged to the world’s first mass tourism since the ancient Romans; it was an image strikingly familiar because it was reproduced in postcards, stereoscope photos, or such crude or sentimental images as might be daubed on lampshades, as souvenirs, by the lady’s children.

The crimson-and-gold lampshades of the house, though, didn’t belong to the family. As career expatriates, the Sargents owned little but such clothes and personal effects as they could cram into trunks, portmanteaus, and carpetbags. George Washington could have belonged to them, as Victorians more willingly lugged fragile, oversized, or heavy objects than modern travelers do. But, as the children’s friend Vernon Lee later observed, such “gods or sibyls or stray martyrdoms” were often included with furnished lodgings in Rome.

These opportunistic rentals capitalized on the burgeoning middle-class American tourist market. A few years before, in 1866, fifty thousand Americans had steamed across the Atlantic, as the Sargents had done in an earlier year. Many itinerant Americans sooner or later discovered Rome—often rapturously—confident that the American Republic, with its own Capitol Hill and just-finished cast-iron Capitol dome, was Rome’s successor. During the fashionable winter season, the Sargents could read listed in Roman newspapers a thousand names of visiting Americans. And those were only the prominent ones, notables who wished to trumpet their arrival to fellow Bostonians, New Yorkers, or Philadelphians.

Mary and Fitzwilliam didn’t listen for such fanfares. They hardly belonged to any social register, though Dr. Sargent was relieved to find “a good many of our old acquaintance still here, who seem glad to see us again.” He and his lively wife mixed primarily with other half-rich Americans (life in Europe in the nineteenth century cost half as much as in the United States) traveling in pursuit of their health. Such was Mary Sargent’s official excuse for their quixotically changing residences.

Yet the family thrived on exile, finding it much less gloomy than Dr. Sargent, in his stoical disappointment, tended to describe it in his letters. They didn’t live in “a household that quivered on the brink of doom,” as one biographer would later describe it. Thanks to Mary, the family pursued pleasure, day after day, quite robustly—even if it was hard to tell if they were patients seeing the sights or just health-obsessed tourists. Here in Rome the Sargents behaved like sightseers, vigorously visiting churches, museums, and ruins, the children digging at bits of half-buried antique porphyry and cipollino with the tips of their umbrellas.

The young Sargents, especially thirteen-year-old John and twelve-year-old Emily, prided themselves on being veteran travelers. They’d spent time in dozens of European towns and cities. But their current intimacy with the broken immensity of Rome, conducted day after day for a whole winter—for many winters, actually—struck them as more like home than tourism.

John and Emily knew their rooms at 17 Trinità dei Monti from other stays. “Rome seems quite like home to us after having passed so many winters in it,” as their father remarked. What’s more, Mary didn’t hold with the tourist fashion of ordering her family’s dinners from cookshops, delivered in metal boxes balanced on top of a porter’s head. She “kept a white-capped chef,” as Vernon Lee would remember, “and gave dinner-parties with ices.” Even so, her dinners weren’t large, for the family’s income wasn’t. Giving this party was a bold maneuver, an extravagance. Mary did so from deeper motivations, otherwise contained in her paint box and her children’s nursery.

Mary knew she wouldn’t have been able to throw such a party in Philadelphia. Her former home city claimed the oldest art academy in America, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1805 by the self-made patriot-naturalist-painter Charles Wilson Peale. By 1869, years after Mary had left it, Philadelphia had discovered an enthusiasm for art that would eventually yield such distinctive American painters as Cecilia Beaux and Thomas Eakins.

Still, Mary believed that Rome as a haunt for artists threw Philadelphia into the shade. To her romantic sensibility, stimulated by ruins and gardens and decayed grandeur, this imperial and papal city hinted at a higher form of art, built on both classical and Renaissance, pagan and Christian foundations. Especially from her family’s high belvedere of Trinità dei Monti, the city beguiled her and her children with long smoky views over an ancient city of red roofs and as-yet-unexcavated ruins.

Mary had also learned, more practically, that Rome hosted a vibrant international artistic community that was centered, as her family themselves now were, on the Spanish Steps. At the top of the Pincian Hill, guarded by the stone lions of the Medici family, stood the tall, white, two-towered palace that the Sargents knew well. Since 1803 the Villa Medici had housed the French Academy, originally founded by Louis XIV in 1666, an engine of archaeological and artistic study for French painters and sculptors lucky enough to win the prestigious Prix de Rome.

Hardly prize-winning types, Mrs. Sargent’s children and their playmates had been caught in the Medici gardens burning holes in laurel leaves with a magnifying glass, and ejected by a French porter who called them “enfants mal élevés,” badly brought up children.

At the bottom of the hill ran the Via Margutta, an artist’s warren of artists’ garrets, studios, and ateliers that Mary and her children had also rather clandestinely explored. There and elsewhere Mary and her children had encountered artists, American, English, German, French, Danish—expatriates from rich northern countries like the Sargents themselves—during their daily circulation in Rome.

Linking the great oval fountain of the Piazza di Spagna below with the blanched classical façade of Santa Trinità dei Monti above, the Spanish Steps mounted the steep, almost cliff-like slope in sweeping, operatic flights. The Sargents knew these stairs and terraces well and saw that they provided the perfect balustraded stage for sun-browned locals offering themselves for hire to artists. The candidates wore picturesque peasant attire: sheep-fleece vests and bound leggings for men, headdresses and embroidered aprons for the women. Some of them even looked promisingly corporeal beneath their costumes, in case they were needed to serve as inspirations for Hercules, Venus, or Eve.

* * *

Mrs. Sargent’s slim thirteen-year-old son, mounting these steps among the burly, busty, and costumed, had been pronounced a “skippery boy” by dour English observers. Others saw simply “a slender American-looking lad.” Those who knew him better, such as his playmate Vernon Lee—then still known by her birth name of Violet Paget—understood him much better. To her, John was “grave and docile,” a solemn, shy, blue-eyed lad. His brown hair was parted severely on one side, and he dressed in a “pepper-and-salt Eton jacket.”

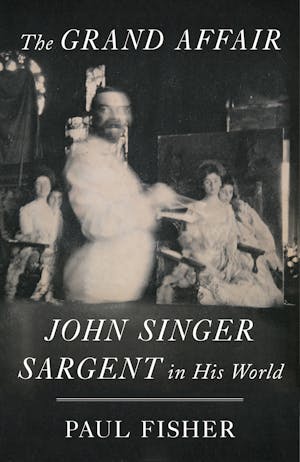

Sargent as a boy of eight, 1864

In his “quiet, grave way,” as Lee remembered, John Sargent was intensely interested in Rome. His prominent pale-blue eyes seemed to absorb everything he saw. He’d also soaked in histories, encyclopedias of antiquities, and guidebooks (Murray’s, published since 1836, was perennially popular). He’d especially liked a scholarly if melodramatic account of imperial Roman life by Wilhelm Adolf Becker called Gallus (1848). John loved reading, and he adored the very air of Rome.

In metabolizing that heady, sometimes disturbing atmosphere, he’d acquired a “remarkably quick and correct eye,” according to his mother. He had a gift for translating the rich chaos into orderly, accurate images. He was already an experienced plein air sketcher who had reason to pay attention to these loitering applicants on the Spanish Steps. As he sized them up, he was already testing out what would become a long and complicated relation with artists’ models. Whatever his “boyish priggishness” made of this spectacle, he found in this farmers’ market of picturesque types his first hints of the enticing interactions of the art world, in which privileged foreign artists like his mother’s friends found uses for a whole demimonde of lower-class Italian models. They were there, on the Spanish Steps, waiting for him.

For Mary’s artist acquaintances, paradoxically, such desperate or enterprising people often supplied the physical patterns for heroes, nobles, gods, and angels. Historical and mythological figures were in vogue. In the 1860s Rome was especially known in the United States for its tribe of American sculptors—on those rare occasions, that is, when these obscure expatriate Italophiles made any impression at all on the busy Republic.

Yet these sculptors had recently received a popular boost from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s romance The Marble Faun (1860), a handsome volume that Mary Sargent had enthusiastically shared with her children. In this novel, sculptors, painters, and models threw themselves into tangled romantic complications, full of the nobility of their vocations and the mystical allure of their snowy marble works. The otherworldly glow of Hawthorn’s tribute to the Roman art world, in fact, had enraptured Mrs. Sargent with a vision of the passionate, exalted beings who inhabited it.

* * *

Mary’s distinguished guests certainly looked the part. They arrived with swagger, anecdotes, and properly accented Italian. Yet they also betrayed some more hidden and illicit aspects of the Rome art world that had fascinated Hawthorne against his will. The guest-sculptors were a colorful and somewhat disreputable lot. What’s more, they gave young John his first model for what artists were and did. They strutted in with versions of liberty, license, and sophistication that granted the boy his first real glimpse of a heady and sexually transgressive world of art.

William Wetmore Story, with his goatee, pince-nez, high forehead, and Salem, Massachusetts, drawl, arrived at the Sargent’s house from his apartments in the storied Palazzo Barberini, now the epicenter of the American art community. In 1868 Story had finished carving his monumental, bare-breasted Libyan Sibyl. But he was better known for a regal and sumptuous Cleopatra (exhibiting one naked breast), which had dazzled the crowds at the London Universal Exposition of 1863. From their collective reading of Hawthorne’s novel, the Sargents knew the fictional version of the Egyptian queen that had featured in the book as “fierce, voluptuous, passionate, tender, wicked, terrible, and full of poisonous and rapturous enchantment.”

Another neoclassical sculptor, Randolph Rogers, who in his studio wore a bohemian dressing gown and beret, showed visitors “every stage of wet-sheeted clay, pock-marked plaster, half-hewn or thoroughly sandpapered marble.” He’d also famously rendered female breasts, notably in his Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii (1853–54), striking gold in the process. Melodramatic storytelling and tasteful seminudity went down well with Victorian audiences and collectors, and it was a recipe that young John would soon find particularly intoxicating.

Like her male colleagues, Harriet Hosmer had also recently sculpted a celebrated female classical figure: Zenobia, rebel queen of Palmyra (1857–59). Even more recently, though, Hosmer had sculpted her own marble fauns—the faun featuring as the mystical centerpiece of Hawthorne’s tale—which manifested an icy fluidity and a somewhat gender-neutral sensuality. Her work also revealed the degree to which seemingly sober Victorian classical statuary, sanctioned by art, channeled complicated sexual energies, in what one recent critic has called the “erotics of purity.” That paradox animated everyone at Mrs. Sargent’s party, including the adolescents waiting for dinner leftovers. It certainly gripped John.

Mary took especial notice of Hattie Hosmer, her most risqué guest. Diminutive, vigorous, obsessed with outdoor exercise, Miss Hosmer dressed rather like a man. The irrepressible sculptor sported short, curly, sharply parted hair and wore a cravat and jacket that might have unnerved Mary’s Philadelphia, where few people had witnessed the iconoclastic cross-dressing of figures like the radical French novelist George Sand. But Hosmer was well-known and at least partly understood in Rome. She’d taken refuge here in 1852, and openly consorted with a young widow, Louisa, Lady Ashburton, who would become her long-term companion.

Inviting the disreputable Hosmer counted as a bold maneuver for Mary and revealed much about her cosmopolitan outlook. Perhaps she shared the opinion of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who regarded the sculptor as a woman who “emancipate[d] the eccentric life of a perfectly ‘emancipated female’ from all shadow of blame by the purity of hers.” Hosmer’s “purity,” however, hinged on how people understood her role as a self-professed “faithful worshipper of Celibacy.” Even so, Mary had made a bold move. And it wasn’t, by any stretch of the imagination, her first.

* * *

Mary Sargent had arrived at her party atop the Pincian Hill by an intrepid and, some thought, a rather devious route. In the 1850s in Philadelphia, she’d often dreamed of Rome, whose glories she’d first tasted as a schoolgirl. Even as a young married woman, she’d continued to ply at her sketchbooks. With Fitzwilliam, to be sure, she commanded a comfortable home—she was after all a doctor’s wife as well as the mother of one small daughter.

But it was the greater sprawl of Philadelphia—that vast brick labyrinth, thickly populated with almost half a million natives and immigrants, startlingly polluted, and torrid in the summer—that would in fact furnish Mary with an opportunity, although it would come through a devastating personal tragedy. The Sargents’ infant daughter Mary contracted an illness that even her doctor father couldn’t accurately identify, much less cure. In July 1853, just two months after her second birthday, the little girl died.

Mary and Fitzwilliam understood that childhood mortality was widespread in their America. It would improve only slowly in coming decades with hard-won, incremental scientific advances in immunology and childhood medicine. But during the Sargents’ young marriage at midcentury, modes of coping with death were changing before their eyes. In the harsher world of previous generations, stoical religion had helped parents accept such devastating losses—a perspective embodied in the grim Protestant culture of New England towns like Fitzwilliam’s hometown of Gloucester, where the thin slate headstones of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century baldly stated birth and death dates and bore images of winged skulls. (In Mary’s Philadelphia, the dominant Quaker denomination favored minimalist grave markers or none at all, reflecting the Quaker belief that the dead, like the living, were all equal in God’s eyes.) Yet, paralleling the changing and softening atmosphere of American families, austere traditional burial customs were now transforming, for the Sargents, into something gentler and more melancholy. Nondenominational rural cemeteries, inspired by more sentimental and romantic visions of death, had begun to emerge in both Fitzwilliam’s native Massachusetts (Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, 1831) and in Mary’s Philadelphia (Laurel Hill, 1836). Fitzwilliam gently mourned the “void left in our family circles” by a child’s death.

In spite of more allowed sentiments, both parents were devastated by the loss of their child. Mary, however, chose another Victorian method of coping with her bereavement. To people today, a trip to Europe seems a peculiar way of recovering from a family tragedy, even if we acknowledge the therapeutic value of a change of scene. But Mary’s doctors—steeped in preepidemiological nineteenth-century medicine—understood disease as intimately related to climatic factors, to cold and heat and especially different kinds of “air.” They also classed as physical, as diseases of the “nerves,” much that we would consider psychological.

Mary knew that, in genteel Philadelphia—as in Boston, New York, and the rest of the polite world—traveling for health, to different climates, usually also to consult European doctors and try different spas and sanatoria, provided one of the few unquestionable justifications of foreign travel, especially for women. Julia Ward Howe, a Bostonian writer and reformer who like the Sargents haunted Rome in the 1860s, acknowledged “health” as a primary and irrefutable justification for travel, and one that “admit[ted] no argument”: “The sick have a right … to go where they can be bettered; a duty, perhaps, to go where their waning years and wasting activities admits of multiplication.” And though Mary wasn’t exactly waning and certainly still young—just twenty-seven in 1854 when she lost her daughter—her bereavement genuinely damaged her health and spirits. For a cure, the logic of the time strongly endorsed European travel.

Whether or not Fitzwilliam medically concurred, the Sargents threw all their resources into the project. On September 13, 1854, Mary, her mother, and her husband boarded the upholstered American luxury steamer Arctic in Manhattan. It was a momentous departure, at the busy, coal-smelling docks on the Hudson River. Though she couldn’t have known it as she crossed the gangplank, Mary wouldn’t return to the United States for more than two decades.

Mary’s cure-tour began in the acknowledged center of expertise, Paris. Here, her irrepressible energy saved her from the claustral, self-limiting role embraced by many female “invalids” of her time, even if that same determination stirred up other complications for herself and her family. Mary remained brisk and energetic. She called her husband “Fitz.” Dr. Sargent didn’t tend to echo her playful form of address: he signed his rather solemn letters home with “FWS” or “FW Sargent.” Mary herself seldom wrote letters, partly because the most important person in her own family, her mother, already traveled with the family and slept in the next room. When she did manage letters, though, they gushed with warmth and teemed with rapturous, underscored words. “Altho’ my words are not skillfully chosen,” Mary later apologized, “[I] express all the love and sympathy I feel.”

Copyright © 2022 by Paul Fisher