1

INTRODUCING GLENN BURKE

“Let’s do this, Silas,” I say to myself.

I’m wearing my baseball uniform in school, and I never wear my baseball uniform here because sixth graders don’t wear their baseball uniforms to Hughes Middle School, unless they want to be nonstop teased by the seventh and eighth graders.

But I’m wearing my Renegades uniform today because today’s the day. Today’s finally the day.

I’m standing on my toes and bouncing at the front of Ms. Washington’s class. All the tables, chairs, couches, beanbags, gaming rockers, and floor pillows are pushed to the sides. The kids are all off to the sides, too. Some of them are standing, but most are sitting. My best friend, Zoey, is in the back, on one of the green-and-black bungee chairs with her feet up on the armrest of the denim couch.

Ms. Washington let me turn the classroom into a pretend baseball field for my oral presentation on a famous inventor. I used blue painter’s tape for the diamond, flattened shoebox tops for the bases, and a balance ball for the pitcher’s mound. And projected on the whiteboard behind me is an image of the packed bleachers of Dodger Stadium on a sunny afternoon.

I don’t know why I’m so nervous. Actually, I do know why I’m so nervous. I know exactly why I’m so nervous …

I take my last breath.

“Introducing Glenn Burke.” I pluck the royal-blue Dodgers cap from the stool to my right and slap it on my head. “When Glenn Burke arrived in the big leagues in 1976, the Los Angeles Dodgers thought he was going to be the next Willie Mays. That’s like saying a soccer player’s going to be the next Messi or a basketball player’s going to be the next LeBron.”

I grab the yellow Wiffle bat propped against the stool, flip it up with one hand, and snatch it out of the air with the other. “Glenn Burke was a five-tool talent,” I say. “Five-tool talents don’t come around that often.”

“What’s a five-tool talent?” Zoey calls out.

“Good question,” I say, pointing the bat.

Zoey learned her lines Wednesday after school. She and I hang out at her house every Wednesday.

“Five-tool talents have all the skills,” I say, walking across the room to home plate. “One. Five-tool talents hit for average and put the bat on the ball.” I take a swing. “Two. Five-tool talents hit for power and can blast the ball out of any park.” I take a bigger swing and watch my imaginary home run soar over the fence. “That ball is outta here!”

I shoot the bat across the floor and jog to first. “Three. Five-tool talents can fly. They steal bases and take extra bases.” I run to second, slide, pop up, and then head to third. “Safe!”

I grab my glove off the stool and crow-hop back to the front of the room. “Four,” I say. “Five-tool talents can field. They catch everything that comes their way.” I pound my glove, feel for the whiteboard, and then pretend I’m taking away a home run with a leaping grab. “Web gem!”

I take the invisible ball out of my glove and fire it back to the infield. “Five. Five-tool talents can throw. Their arms are cannons.” I mic-drop my mitt. “Five-tool talents don’t come around too often.”

I’m killing my oral presentation. Ms. Washington’s looking at me the same way she looked at Daphne during her presentation on Lizzie Magie, the woman who invented Monopoly, and the way she looked at Kyle during his presentation on Stephanie Kwolek, the scientist who invented Kevlar, the material used in bulletproof vests. Ms. Washington’s big into theater—she always directs the musicals up at the high school—and loves it when kids turn their presentations into performances. That’s what Daphne and Kyle did last week, and that’s what I’m doing right now.

I peep Zoey, who’s double-dimple grinning at me like she does when we’re standing on her living room couch singing karaoke. Zoey’s got deep dimples in both cheeks, and her double-dimple smile is her super-happy smile.

Zoey knew how badly I wanted to present today. She saw how pumped I was yesterday when Ms. Washington told me I’d be up second this afternoon. But not even Zoey knows why I didn’t want to wait until Monday. Not even Zoey knows why I needed to do this today.

“Heading into the final weekend of the 1977 baseball season,” I say, “the Los Angeles Dodgers had a chance to make history. No team had ever had four players hit thirty home runs in the same season, but for the Dodgers that year, Steve Garvey, Reggie Smith, and Ron Cey all had more than thirty, and Dusty Baker had twenty-nine.” I pick up the Wiffle bat and head back to the plate. “The Los Angeles Dodgers were one Dusty Baker home run away from the record books.”

I take a big swing and pretend to miss. Then I take another big swing and pretend to miss again.

“Dusty didn’t hit a home run on Friday night,” I say. “He didn’t hit a home run on Saturday either. He had one last chance on Sunday afternoon, but for the Dodgers to make history, Dusty Baker would have to hit that home run off James Rodney Richard, the hardest-throwing pitcher in all of baseball.”

I leave the bat at the plate, head for the balance ball, and pull the old-school Astros lid out of my back pocket. The ’Stros are my favorite team, which is why I have the vintage hat, a Christmas present from last year. I put it on over my Dodgers cap and imitate J. R. Richard’s high-kick motion.

“Dusty didn’t hit a home run in his first at bat,” I say. “He didn’t hit a home run in his second at bat either. Dusty had one last chance.”

I leave the Astros cap on the balance ball and return to home plate, and as I step back into the pretend batter’s box, Zoey starts the music on her phone—the organ music they play at ballgames that gets the fans clapping. Zoey begins to clap, Ms. Washington joins in, and then so do a bunch of other kids.

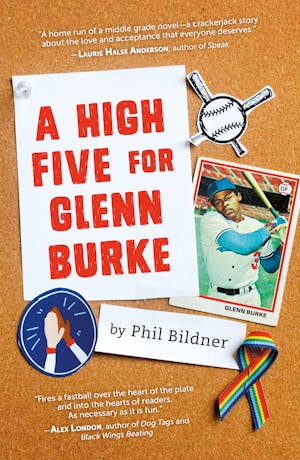

I brush the number three on the sleeve of my Renegades jersey. I wear number three because Benjamin Franklin Rodriguez, my favorite character from The Sandlot—the greatest movie ever made—wore number three when he played for the Dodgers as a grown-up in the movie, which happened to be the number Glenn Burke wore when he played for the Dodgers. But I didn’t know Glenn Burke wore number three until I was researching him and came across the photo of his 1978 Topps baseball card. When I did, I almost fell off my bed.

“Strike one,” I say. “Ball one. Strike two.” I stare at the imaginary pitcher and announce the play-by-play. “One-and-two to Baker. J. R. Richard rocks into his windup, around comes the arm, the one-two pitch…”

I take a mighty swing and flip the bat.

“Home run!” I’m still play-by-playing. “Home run!” I raise my arms and start circling the bases. “Dusty Baker has blasted a home run into the bleachers and the Dodgers into the record books. Home run!”

“Dus-ty!” Zoey stands and cheers. “Dus-ty!”

“As Dusty Baker headed for home,” I say, slowing down as I round third, “Glenn Burke bolted from the on-deck circle, and as Dusty crossed the plate, Glenn threw his right arm into the air and waved his hand wildly. Dusty smacked Glenn’s right hand with his own right hand.”

Zoey and I act it out.

“A high five,” I say. “The very first high five.”

Zoey bows and returns to her seat. I remain at the plate.

“Glenn Burke stepped into the batter’s box.” I pick up the bat. “Unlike his Dodgers teammates, he hadn’t been slugging home runs all season. The rookie was still looking for his very first home run in the big leagues.”

I take another mighty swing and flip the bat again.

“Home run!” I say, admiring the make-believe blast. “Home run!” I sprint around the bases and jump on home plate. “When Glenn Burke reached the dugout, his teammates greeted him with handshakes and helmet rubs.”

I slap hands with Connor and Kaitlyn and bend down so Nolan and Mia can pat and rub my head.

“Dusty Baker threw his right arm into the air and waved his hand wildly,” I say. “And Glenn Burke smacked Dusty’s right hand with his own right hand.”

Zoey pops back up, and we act it out again.

“A high five,” I say. “The second-ever high five. A handshake was born.”

I dart back across the diamond, spring off the balance ball, and land in front of the whiteboard.

“Suddenly, the high five was everywhere,” I say. I’m up on my toes again and waving my arms. “It spread through baseball. Then it spread through soccer, football, basketball, and hockey. To all sports around the country, to all sports around the world. Soon people were high-fiving in classrooms and courtrooms and boardrooms. On playgrounds and campgrounds and fairgrounds. In movies and on television. Even the pope was high-fiving, and the president of the United States was high-fiving!”

I slide over to Ms. Washington and hold up my hand. She gives me a high five.

Yeah, I’m absolutely killing my oral presentation.

“Nearly a half century later,” I say, “the high five lives on and on and on. It’s now a universal greeting, known around the globe as a gesture of excitement, a gesture of joy, a gesture of unity, and a gesture we feel in our souls.” I thump my chest. “A gesture that began with Glenn Burke, the man who invented the world’s most famous handshake.”

I let out a breath.

I did it. I actually did it. Nobody knows what I really did, but I did it. I finally did it.

2

RENEGADES ARE READY

The first pitch to Theo sails outside.

“Hey, pitcher, what’s the matter? Why you tryin’ to walk our batter?” I chant.

I’m standing on the end of our bench next to Malik, who’s my best friend on the Renegades and whose mouthguard’s dangling out of his mouth like Steph Curry’s. We’re leading the cheers in our dugout, and all the other Renegades are lined up next to Malik, and just like we have been all game, we’ve broken out our rally caps. Whenever we’ve needed a big hit this afternoon, we’ve held our caps upside down by the brim and shaken them like rattles at the Titans pitcher. It’s worked every time, and in baseball, when something’s working, you keep on doing it.

“Let’s go, Sixteen.” I call Theo by his number. “Be alert, Twenty-One,” I shout to Luis on second.

There’s one out in the bottom of the last inning, and the game’s tied at five, but in my mind, we’ve already won the game and swept this doubleheader. I know Theo’s about to drive Luis in with the winning run because the Titans are playing not to lose, and when you play not to lose against the Renegades, you’ve already lost.

We schooled them 8–1 in the opener. Theo threw a complete game, striking out nine and giving up only two hits, just like the ace of a staff is supposed to. He was also a beast at the plate, driving in five—three on a home run that landed in the next zip code.

In this game, the Titans led 5–0 after two, and they should’ve been up by a lot more, and they know it. They left ducks on the pond—runners on base—in the third and fourth, and against the Renegades, you best not waste scoring opportunities, because it’s going to come back to haunt you. Inning by inning and run by run, we chipped away, and a minute ago, we tied things up when I scored all the way from first on Luis’s base knock to right.

The next pitch lands in the dirt. The catcher blocks the ball with his chest protector, gobbles it up, and checks Luis down at second.

“Hey, pitcher, look at me, I’m a monkey in a tree,” I sing.

Malik grabs his mouthguard and starts scratching and making monkey noises. “Ooh-ooh, ee-ee. Ooh-ooh, ee-ee.”

“Ooh-ooh, ee-ee!” Ben-Ben, Carter, Jason, and Kareem all join in. “Ooh-ooh, ee-ee!”

I’m always leading the chants, doing whatever I can to keep the Renegades loose and fired up. I’m never able to sit in the dugout, even when I’m not in the game. I’m always hopping on and off the bench, pacing back and forth, rattling the safety fence, and spitting sunflower seeds.

That’s what Glenn Burke was like when he played for the Dodgers. Glenn Burke was the life of the dugout. I’m the kid version of Glenn Burke, except I’m not black and built like a tank. I’m white, floppy-haired, and skinny as a rail.

None of my teammates know about my Glenn Burke presentation because I’m the only one on the Renegades who goes to Hughes. I would have never done my project on Glenn Burke if any of the Renegades went to my school.

I still can’t believe I did it, but I did. I really did. Now I have to tell Zoey. Yeah, she was in class, but not even she knows what I really did. I need to tell her.

I bump Malik with my hip. He bumps me back.

Malik likes to cheer and chant and goof around almost as much as I do. He’s not able to sit still either, which is probably why we became friends in the first place. But Malik and I are only baseball-team friends, because we go to different middle schools and live twenty minutes apart. Even though we’ve been teammates the last three seasons, we’ve never hung out outside of baseball.

Copyright © 2020 Phil Bildner