CHAPTER 1

Santa Clara, CubaApril 1961

This is not my home.

Tía Carmen’s kitchen doesn’t have my model of a P-51 Mustang or scattered pieces of Erector set. Instead of a mango tree out front with a tocororo nest in its branches, there’s a crowd of soldiers, slapping one another on the back and firing their rifles into the night air.

My cousin Manuelito slaps another domino down on the table. “Doble ocho, tonto,” he cackles. His stubby fingers fidget over the remaining dominoes in front of him.

“Don’t call me stupid,” I say, narrowing my eyes.

Mami paces behind Manuelito, twisting a red dish towel in her hands. She reaches for the cross at her neck, and I hear her mumble the Lord’s Prayer. “Padre nuestro, que está en el cielo.”

Sharp shouts outside Tía Carmen’s house cut off the rest of her prayer.

“Mami?”

My little brother, Pepito, starts to get up from his chair, but Mami puts her hand on his shoulder.

“Don’t worry, nene. It’s fine.”

Mami and Tía Carmen exchange worried looks. They may be fooling Pepito, but they’re not fooling me. Fidel’s soldiers defeated a force of Cuban refugees who had fled to the United States and were trained by the American government. The refugees tried to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, but Fidel’s army quickly overtook them. From what Papi told me, this was our last hope of ridding our island of Fidel’s oppressive government.

“Keep playing, Cumba,” Mami says as she waves her hand at me. The candle on the table where Manuelito and I sit flickers, bouncing long shadows of dominoes across the plastic floral tablecloth.

I try to focus on the tile in my hand, but the shouting outside increases. I shake my head and slap another domino down on the table. “Tranque. I blocked you.”

The waistband of my pants digs into my stomach, and I fidget in my folding chair. The chair squeaks, prompting Mami to give me a quick look from the window.

She dries the same bowl over and over until the dish towel is limp in her hands. Tía Carmen tries to turn the radio up, but Mami snaps the volume dial down.

“I don’t want to listen to that foolishness,” she mutters.

Manuelito looks at me from across the table. The light from the candle turns his eyebrows into thick brown triangles, and his fat cheeks cast a shadow on his neck.

“Your papi come home yet?” He sneers, and the candlelight elongates his front teeth into fangs.

Tía Carmen crosses the kitchen in a blur of blue cotton flowers. She slaps Manuelito on the back of the head, his neck snapping forward and flipping his brown hair into his eyes.

“Cállate, niño,” she hisses.

Manuelito’s being told to shut up offers little consolation. He doesn’t know. He has no idea that at this moment, my papi is tucked in a corner of our house, hiding from Fidel’s soldiers. He sent us to Tía Carmen’s when Radio Rebelde blasted the news of the impending Yanqui invasion.

“I don’t want you here if they come for me,” he said as he ruffled my hair, the smile on his lips failing to hide the nervousness in his eyes. Fidel’s soldiers were rounding up anyone who had worked for former President Batista. Papi was a captain in the army. Even though he was just a lawyer in the Judge Advocate General’s unit, those two bars on his uniform made him look important.

I wrap my feet around the legs of the folding chair to keep myself from kicking Manuelito. He’s a year younger than I am, and he prides himself on being the most annoying eleven-year-old in the world.

Manuelito lowers his head closer to the table, his eyebrows thickening and his fangs growing longer. He whispers, “It’s not gonna work, you know. Fidel always wins.”

I unwrap my left foot from the chair and kick him in the shin. Manuelito winces. That was for Papi.

Tía Carmen turns up the radio by the sink, and Mami purses her lips. “¡Aquí, Radio Rebelde!” shouts a deep voice from the speaker. “The Yanqui imperialists have failed, are failing, and will fail to overthrow our glorious revolution!”

News of the Bay of Pigs invasion fills the kitchen. Fidel has been giving speech after speech, taunting the Cuban exiles and their American supporters.

The anthem of the 26th of July Movement, Fidel’s government, blasts from the radio, and Mami turns it off.

I sigh. Manuelito, Pepito, and I try to concentrate on our domino game. But it’s no use. You’re supposed to play with four people. Normally, Papi would’ve been our fourth.

Pepito lays down a new domino, and his eyes grow wide. “¡Ay, caramba! ¡La caja de muertos!”

He slaps his hand over his mouth before Mami can hear him curse. Pepito has always thought the double-nine tile was bad luck because it’s called the dead man’s box. When I hear the stomps and shouts outside, I’m reminded that there are worse sources of bad luck than a little white tile.

“It’s okay, hermanito. Don’t worry,” I reassure him.

I swipe my hand over the dominoes we’ve laid down, erasing our careful rows. Game over. I show Pepito how to line up the dominoes in front of one another and knock them down in a cascade. He claps his chubby hands and starts to set up the dominoes himself, sticking out his tongue in concentration.

Mami sets down a glass of water in front of me, and I pretend not to notice her shaking hand. A sharp pop of gunfire explodes outside, making us all jump.

“What are they doing?” Pepito asks.

Mami lets out a long sigh. “They’re celebrating, nene.”

Pepito scrunches up his face. “That doesn’t sound like celebrating to me. There isn’t any music.”

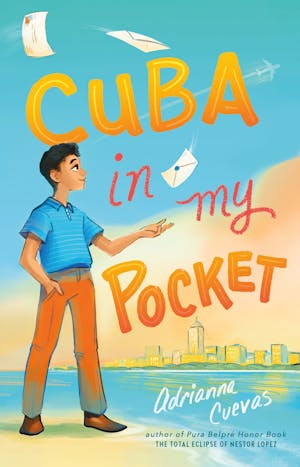

Copyright © 2021 by Adrianna Cuevas