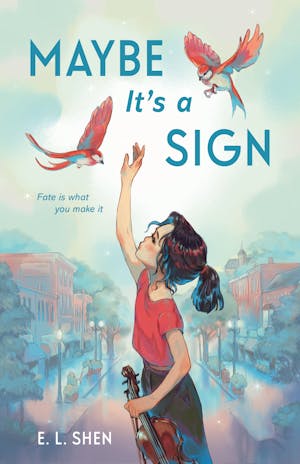

THE CONCERT

Dad always said the viola was lucky. He used to remind me every time I got sick of practicing or whined about another concert or competition. In careful detail, he reminisced about the day we first walked into the Hartswood Music Store on the corner of Eighth and Franklin—from the twinkle of the silver bell when we opened the door to Mr. Miyazaki’s thin, wispy beard and wrinkly forehead as he welcomed us into his shop. For a while, my older sister, May, played the piano, so my parents thought I’d pick that instrument, too.

But no.

At first, I only cared about the decorations. The weird little busts of Beethoven and Bach and the funny crank of the music stands when you bent them backward. But at some point, I guess, I pointed at a pair of violas hanging off to the side, separate from the violins and the giant cellos. Dad was thrilled. Lucky things always came in pairs. Every good Chinese person knew that. And I had zeroed in on two violas—the instruments that would therefore make me the luckiest, would bring me the most happiness. Dad bought them both. The first was for good fortune and for my future children “who might one day want to play the viola, too” (barf). The second was, of course, for me. Once I curled my fingers around the pegbox and headrest, my future became clear. I was Freya June Sun: the violist.

Dad was wrong about one thing, though. I’m not lucky. Because while I still have my viola, he’s been gone for eight months and five days. One afternoon in August, while I was at the kitchen table reading The Canterbury Tales for my summer reading assignment, Dad was at work, in some sort of accounting meeting with his coworkers. And then just seconds later, he was apparently on the floor, his heels making right angles with the blue-gray carpet. The doctors called it a massive myocardial infarction. A heart attack. I call it cosmic punishment.

Now, it’s just Mom dragging May and me through the Hartswood Middle School parking lot, my patent-leather Mary Janes kicking up gravel. My viola case knocks against my dress, and I wonder if I can hit it hard enough against my thighs that I’ll damage the instrument and won’t have to play my solo.

“Stop doing that,” Mom scolds. “We’re going to be late.”

“It’s fine. Mr. Keating won’t care.”

Or more like he’s given up on caring. We’ve been late to so many rehearsals and nearly every concert since the start of the school year. Why should my conductor expect anything different this time around?

Case in point: As we near the lobby’s double doors, May putters fifteen feet behind us, rummaging through her purse. My sister hates dressing up, but tonight she has on a plaid miniskirt and a cream knit sweater. It’s not because she thinks my seventh-grade spring concert is important. It’s because Lucas Vanderpool will be there, watching his younger brother bang out random notes on the bass. I told her Lucas Vanderpool’s face looks like a pinched rat’s, and he is literally the dullest person on the planet, but May is reapplying lip gloss for him anyway. She never listens to me.

We’re almost inside. I close my eyes.

If a car honks in three seconds, it’s a sign from Dad that I don’t have to play.

One thousand and one.

One thousand and two.

One thousand and three.

Silence.

Okay, five seconds.

Mom lunges ahead, waving us in from the doorway. May finally catches up to me, her breath hot on my shoulders. She drops her lip gloss in her bag before pulling out a white headband and stuffing it in her hair. I freeze. Choosing to wear white in your hair is like asking for the ancestors to smite you. You only wear it when someone’s died. Dad’s funeral was the first time I’d worn an eggshell ribbon in my hair. It felt like rope tightening around my scalp. When we got to the church, I was messing with it so much, it almost slipped out of my ponytail. Grandma wordlessly stopped my fiddling. I knew what she meant as soon as her fingers curled around my wrist. On that day, white belonged in my frizzy hair. White was for the dead.

The ribbon’s still hidden in my jewelry box, beneath silk scrunchies and tchotchkes from our old summer vacations in Florida. I don’t dare wear it or even look at it. But I can’t throw it away, either.

“May,” I say, a sudden bite in my voice, “take it off.”

“Hmm?”

My sister smooths down her strands and bats her eyes under clumps of mascara. I drop my viola case on the ground.

“Seriously, May. Take it off. Now.”

“Don’t seriously me. It’s a headband. You’ll live.” She points at her sweater. “And it matches.”

Before I can snap back, I hear the click-clack of Mom’s heels as she trudges back to us, her phone waving wildly in our direction.

“Does no one see what time it is? Late. We are late.”

I shake my head. “I’m not moving until May takes it off.”

My sister scoffs. I can’t believe she doesn’t care. Dad taught us the rule about the color white. She always followed it when he was alive. And besides, she could wear a purple headband. Or pink. Or blue. Or, better yet, red. That’s a lucky color. It’s like she actively wants me to bomb my solo.

Our mother’s eyes dart from May to me. She rubs her temples and takes long, deep breaths. We wait for her verdict.

“May,” she says, “for your sister’s sake, please take off the headband. You look fine without it.”

“But—”

“Nope. No. End of discussion. Let’s go.”

With that, Mom barrels back through the double doors, and May rips off her headband, scowling. We lock eyes, and I wait for her to say it: Dad’s superstitions were ridiculous. You’re ridiculous. No one cares about those silly Chinese wives’ tales except you, and that’s because you’re immature and naive and you refuse to grow up. But she doesn’t say anything. She just stomps into the lobby.

I kneel down to pick up my viola case, its handle heavy in my palm. This whole concert is turning out to be a disaster before it’s even started. Maybe that’s a sign. Maybe I should just go back to the parking lot and hide behind the car until the whole thing is over. I shiver. Even though it’s early April, the air is sweet and humid. I shouldn’t be cold. The glittery polka dots on my taffeta dress feel rough under my palms. It’s the same dress I wore to the winter holiday concert a year and a half ago. We played the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah with the choir, and the moment the first note rang out, Dad stood up because it’s supposedly a tradition going back hundreds of years, from when some British king stood for the Hallelujah Chorus at its premiere.

Dad insisted it was important to respect traditions, even though the king was long dead and he wasn’t even our king. I thought it was embarrassing—Dad towering over the seated audience with his puffy hair so everyone could immediately tell we were related. I cowered behind my music stand as he bobbed his head to the squeals of the off-key choir.

Eventually, everyone else stood up, too, either because they shared some strong feelings about respecting a dead king from the 1700s or they thought he was getting an early start on giving his kid a standing ovation. By the end, you could hardly hear the out-of-tune sopranos or my many mistakes amid the crowd’s premature roars and applause.

After the concert, we all got ice-cream cones from the shop down the street, and Dad bragged to my classmates’ parents that he was a trendsetter. I didn’t say a word. All I wanted to do was go home, bury myself under the comforter, and pretend the whole thing hadn’t happened. But if I could go back in time, I’d look up from my melting vanilla cone and wrap my sticky arms around Dad’s stomach and tell him: Yes, you’re a trendsetter. You’re the coolest dad ever.

I clench the taffeta in my fist and focus on the parking lot so I don’t cry. There are no stragglers anymore—just rows and rows of cars under a hazy, muddy yellow sky. I am trying to remember my solo’s opening notes, but all I can think of are streams of vanilla ice cream sliding down the spaces between my fingers like blood. Somewhere in the lobby, Mom is screeching my name. I stare at the sinking sun.

“Please,” I whisper, “don’t make me play.”

Not a single car honks in response. I drop my head and stare at my feet. And then, in a reflection of my Mary Janes, I spot it. A red bird. No, two red birds. I look up and see the pair perched in a small tree on the edge of the sidewalk. Their wings are pulled tightly against their backs—bright blobs that can’t be missed. As I get closer, the bigger one croaks lightly. I’ve never seen birds like this before. Not in Westchester, where every animal is gray or brown and boring. Not even in Orlando, where the birds are merely shadows hiding from the stifling heat. Somehow, these red birds remind me of the paper envelopes Dad slid under our plates at Chinese New Year dinners, the block of red rosin I use on my viola bow, the stories Mom and Dad used to tell over sweet jasmine tea that came in red tins. I do a mental calculation. A pair of birds, the color red. Lucky all around. Dad’s finally done it. He’s sent me a sign.

I step closer to the tree, and the birds dive into the air, swooping upward and skimming the school’s rooftop solar panels. In an instant, they’re gone. I press my viola case against my side. I know what I have to do.

SPOTLIGHT

When I stumble through the double doors and into the rehearsal space (which is really just the middle school cafeteria), Mr. Keating breaks out in a grin so wide you’d think it was Yo-Yo Ma waltzing down the aisle instead of me, a short, nerdy seventh grader with dress sparkles stuck to her cheeks.

“Ah, Freya,” he says as the entire room turns to stare at me, “just in time.”

I offer an apologetic half smile as he beckons me to the piano so I can tune my instrument. I make my way over and take my instrument out of its case. Even though my back is turned, I just know the rest of the orchestra is glaring at me and muttering stuff like: Oh, look, it’s Freya June Sun, the girl who’s never on time yet somehow always nabs the solo. (Well, they’re probably not that succinct, but you get the point.)

Stephanie Schmidt, the concertmaster, sniffs from her seat in the first row. I don’t need to look at her to know she’s the unofficial leader of the orchestra’s glares. The solo in Senaillé’s piece Allegro spiritoso is meant for either a violin or a viola. Everyone thought it would go to Stephanie—particularly because she’s been not-so-quietly playing it during our five-minute breaks—but, no, Mr. Keating just had to give it to me.

Our mustachioed conductor bangs out an A, the piano note echoing against the cinder block cafeteria walls. When I squeak out my own note on the viola, the screech of my bow bounces off the ceiling. I don’t know why we have to warm up in the cafeteria. Why couldn’t Mr. Keating pick someplace with worse acoustics, like a janitor’s closet, which could never fit forty-five people so I’d have to just sit the whole thing out? Or, better yet, why don’t I go hide in the janitor’s closet and accidentally lock myself in so I won’t have to play?

I try to concentrate on tuning—twisting the pegs this way and that, slowly inhaling the smell of rosin and boy sweat and yesterday’s cafeteria meatloaf. My eyes focus on my viola’s deep cherrywood body until it blurs and all I can see are those two red birds in the parking lot, appearing like magic. Lucky in every way.

The last time I had luck like that, I was in fourth grade. I had to give an oral presentation on what I thought was the eighth wonder of the world for social studies. The night before, I was completely unprepared, had maybe four sentences written, and could barely remember the words Niagara Falls (my chosen “eighth wonder”). I thought I was going to throw up. But then Dad came into the kitchen while I was face-planting on my textbook and told me about the history of the number eight.

“It’s the luckiest number,” he said, “because in Mandarin, eight is pronounced ba, which sounds like fa. And fa means ‘fortune.’”

“Uh-huh,” I had mumbled, ignoring him in favor of permanently stamping my forehead with textbook ink.

“I’m serious,” Dad insisted. Then he started rambling on and on about how the number eight is associated with success and wealth, so my presentation would have to go amazingly since it’s on the eighth wonder of the world. There was no possible way I could fail or vomit or both.

I didn’t believe him. But the next morning, I gave my presentation, and somehow the words flowed out of me like I had become Niagara Falls. I didn’t stammer once. I sounded prepared and informed. My teacher gave me an A. And then directly after social studies, I found seventy-five cents on the cafeteria floor—just enough money to buy the vending machine chips I wanted. Wealth and success. Dad was right. Eight was lucky. Eight was magic.

He’s right this time, too. It doesn’t matter what I want. My father has sent me a sign. A real one. I have to play.

When I’m finished tuning, we file out of the cafeteria and into the hall that leads to the auditorium. We pause backstage, and my stand partner, Xena, shuffles her sheet music, the handle of her bow crushed in her fist. I’d forgotten that this is Xena’s first concert at Hartswood Middle School—she just moved here from California in January. I wonder if she chose the viola because she also accidentally pointed at a pair of violas in a music store when she was six or if she had a more normal reason, like she saw a violist influencer on TikTok (if those even exist) and couldn’t resist playing the most boring instrument in the world.

“You’re gonna be great,” I whisper. “Don’t worry.”

Xena brightens. “Thanks, Freya. You—”

I gently push her into the bright lights of the auditorium before she can say anything else.

Onstage, I find my seat across from Stephanie’s. Even though the audience is mostly cloaked in darkness, I can still make out Mom and May in the third row, conveniently sitting behind Lucas Vanderpool and his parents, of course. My family always sits up front at concerts so they can take good pictures to send to my grandparents. I look over to Mom’s left as she leans forward to find me in the crowd of instruments and middle schoolers. There’s an empty seat between her and an older lady and her grandkids. A spot for Dad. It’s like he’ll walk in any moment, like he’s late after another work call or he stopped on the side of the road on his way here because he saw an injured animal and had to call animal control because not doing so would be really unlucky. Soon he’ll fly in with his phone all charged and ready to video my Big Moment.

I glance down at my sheet music. Dad must have sent the birds because this is my first solo ever. I’ve never had one before. He’s probably really excited in heaven. If he were actually about to walk through those auditorium doors, he’d already have my part memorized just so he could appreciate how beautiful it was when I played it or something cheesy like that. Except this time, I don’t think I’d find it that cheesy.

Instead, as Stephanie tunes us again and Mr. Keating walks onstage to a smattering of applause, the only people I do see scurry in late are my best friends, Darley Banerjee and Billie Karras. We’ve been the tightest of trios since field day in second grade, when we all had to run the relay race together. Darley plays soccer, so she was like our team captain, peptalking us into a surprise win.

Copyright © 2024 by E. L. Shen

Copyright © 2024 by Sher Rill Ng