1. On interruptions

I remember reading Alice Walker's essay in my twenties about how a woman writer could manage to have one child, but more was difficult. At the time, I pledged to have no more than one, or at the very most two. (I now have three.) I also remember, before having children, reading Tillie Olsen, who described with such clarity: thinking and ironing and thinking and ironing and writing while ironing and having many children—she herself had four. I myself do not iron. My clothes and the clothes of my children are rumpled. The child's need, so pressing, so consuming, for the mother to be there, to be present, and the pressing need of the writer to be half-there, to be there but thinking of other things, caught me—

Sorry. In the act of writing that sentence, my son, William, who is now two, came running into my office crying and asking for a fake knife to cut his fake fruit. So there is also, in observing children much of the day and making theater much of the night, this preoccupation with the real and the illusory, and the pleasures and pains of both.

In any case, please forgive the shortness of these essays; do imagine the silences that came between—the bodily fluids, the tears, the various shades of—

In the middle of that sentence my son came in and sat at my elbow and said tenderly, "Mom, can I poop here?" I think of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own and how it needs a practical addendum about locks and bolts and soundproofing.

But I digress. I could lie to you and say that I intended to write something totalizing, something grand. But I confess that I had a more humble ambition—to preserve for myself, in rare private moments, some liberty of thought. Perhaps that is equally 7.

My son just typed 7 on my computer.

There was a time, when I first found out I was pregnant with twins, that I saw only a state of conflict. When I looked at theater and parenthood, I saw only war, competing loyalties, and I thought my writing life was over. There were times when it felt as though my children were annihilating me (truly you have not lived until you have changed one baby's diaper while another baby quietly vomits on your shin), and finally I came to the thought, All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow. And then I could breathe. I could investigate the pauses.

I found that life intruding on writing was, in fact, life. And that, tempting as it may be for a writer who is also a parent, one must not think of life as an intrusion. At the end of the day, writing has very little to do with writing, and much to do with life. And life, by definition, is not an intrusion.

2. Umbrellas on stage

Why are umbrellas so pleasing to watch on stage? The illusion of being outside and being under the eternal sky is created by a real object. A metaphor of limitlessness is created by the very real limit of an actual umbrella indoors. Cosmology is brought low by the temporary shelter of the individual against water. The sight of an umbrella makes us want to feel both wet and dry: the presence of rain, and the dryness of shelter. The umbrella is real on stage, and the rain is a fiction. Even if there are drops of water produced by the stage manager, we know that it won't really rain on us, and therein lies the total pleasure of theater. A real thing that creates a world of illusory things.

I have an umbrella with a picture of the sky inside. My daughter Anna said, when she was three and underneath it, "We have two skies, the umbrella sky and the real sky." When I went out with her in the rain recently without an umbrella, she said, "It's all right, Mama. I will be your umbrella." And she put her arms over my head.

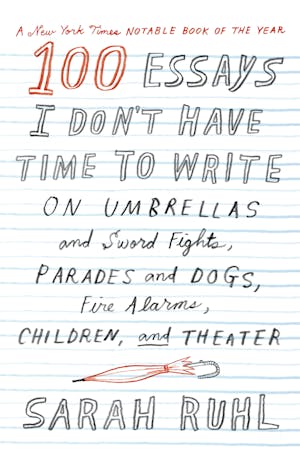

Copyright © 2014 by Sarah Ruhl