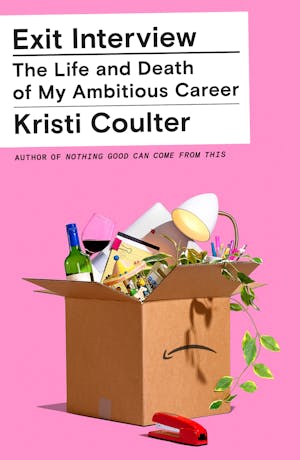

1IMPLAUSIBILITIES

I can tell people don’t believe me when I say my co-workers kept bottles of booze on their desks, or that they sometimes popped beta-blockers before meetings with Jeff Bezos, or that I found out about the Kindle and the drones and Whole Foods on the internet like everyone else. It’s hard to swallow that our laptops were sometimes repaired with duct tape, or that my psychiatrist credited Amazon employees for his second home in Hawaii, or that the mere existence of Amazon warehouses could slip my mind for years at a time, never mind what went on inside them or what it might be like to work in one. I learned of Amazon delivery trucks when I saw one broken down on my street. I learned that Amazon was firing people by algorithm by reading Bloomberg. “But you were right there,” I’ve heard, at which times I explain that there’s no such thing at Amazon, that it’d be like being right there in an ocean or a field of static. That often my only right there was whatever had to happen in the next thirty minutes to incite or narrowly avert catastrophe or catapult me into a future I both dreaded and desperately wanted. I can see from people’s faces that it’s not quite plausible, or that it’s plausible but they just don’t like it. “You were a good German,” a drunk man once said to me, pleased with himself because he thought he was the first. Most improbable of all is when I say parts of it were astounding and fun, that for twelve years Amazon supplied me with a high-grade lunacy I didn’t know I needed until I touched it and my ambition bloomed like neon ink in water. That doesn’t sound fun, the faces say, or that shouldn’t have been fun. To which my only possible response is, I’m not telling you what was right or good. I’m telling you what went down and how it felt.

2THE PULL

Title: Senior Manager, Books & Media Merchandising

Location: Seattle, WA

Date Posted: January 6, 2006

Do you want to change the world? Are you passionate about helping customers shop online? Do you have the stamina of a jacked-up mountain goat and boundaries fairly described as “porous”? Amazon.com is seeking a North American leader for its Books and Media Merchandising teams. In this role, you will own the merchandising, editorial, and email content for five Amazon storefronts, leading multiple editorial teams in a 24/7/365 demand-generation process. You will drive relentless, and we seriously fucking do mean relentless, improvement in merchandising content on Amazon and directly impact free cash flow. You will also build new internal content-management tools with Band-Aids and Scotch tape by working closely with understaffed technical leaders in a highly matrixed environment (that is, one in which you have absolutely no authority or leverage).

Amazon’s culture is exciting, fast paced, and dynamic. Like, highly dynamic. If you end up hating this job, no worries! It will be unrecognizable in six months anyway. We offer competitive pay and a benefits package that is not the worst. Employee amenities include a desk and laptop, plus the option to request sandpaper for your desk (you’ll see) and a coat hook from Facilities (please allow ten days for delivery).

Job Requirements:

5+ years experience leading content or editorial teamstrack record of delivering large, cross-functional, complex, customer-facing products under circumstances verging on psychoticintense fear of failureability to be dropped into any situation with a blowgun, tourniquet, and Excel 97, and figure shit out fastthick hide/peltAlso Highly Desired:

superior physical staminastay-at-home spouseacute impostor syndromeEEOC Statement:

Amazon.com technically counts as an Equal Opportunity Employer.

Copyright © 2023 by Kristi Coulter

Lyrics from “Mirrorball.” Words and Music by Ben Watt and Tracey Thorn. Copyright © 1996 SM Publishing UK Limited. All rights administered by Sony Music Publishing (US) LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.