FRIDAY

WE ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR TELLING THIS STORY, mostly because Coral cannot. She just discovered her brother dead in his apartment. Suicide. Coral’s brother, Jay, lived in Long Beach, California. It was a cheap apartment even though he could afford more. Jay didn’t like the idea of moving, because no one really likes the idea of moving, especially men nearing forty. People like to dream of being elsewhere and suddenly having all their things elsewhere with them, but moving is what Coral refers to as some bullshit. We’ve done the research. The apartment peeked out from between a row of houses and one other multiunit building. Bougainvillea, gardenias, and other low-water-tolerant plants that add pops of color to lazy landscaping crawled along the facing. Long Beach was an oily, salty city nicknamed Weirdbeach by those not likely to fly a gay pride flag on their lawns anytime soon. The long, sleepy horns of boats at the extremely active port moaned into the night. Coral had finished a brief conversation with Jay about eleven minutes before arriving at his apartment. He didn’t mention the suicide. We are certain.

There wasn’t much blood. There wasn’t much blood visible right away, that is. We believe this is why Coral didn’t notice when she walked in. The studio was dark, the way Jay liked it, with blue walls, a blue sofa, a blue entertainment center and blue rug. It was like diving into the ocean at any time of day, if the ocean were hot as fuck, humid, and smelled like burned bacon and coconut-scented candles. Coral thought the place was empty but was startled when she saw the shape of Jay under a blanket on his bed.

It was so quiet I thought no one was home, Coral said.

She went to the kitchen and looked in the refrigerator.

You need to go to the grocery store. Where’s the water? It’s hot as fuck in here. Yeah, I was surprised when they offered me the deal, but now that it’s signed I can talk about it, you know. I know you knew something was up and I don’t keep people in suspense with hints and things, but it’s like a pregnancy. You don’t talk about that shit until it’s deep in the process and you know for sure. That’s what people say, at least. Men don’t think about that junk. Let me give you another metaphor, since that is what I do. So it’s like in football when you talk about who is going to win or not. You don’t jinx that shit by oversharing why you know. Or maybe that is what you do. Y’all be extra with that down to the mathematical. Mofos walking around with 300 credit scores can recite every statistic from 1967 to the present about some team. How are you still under that blanket?

That’s when Coral walked close to the body of Jay in the dim light and saw what we know. She handled it as well as could be expected, which is not well in the long run, not well at all. Some people scream at death. Coral fell down with vertigo. Everything silent. The heart causes that, pumps all the blood to all the extremities so it feels like your head is going to pop, and your fingertips go numb with the pressure. She tried to grip her phone and couldn’t. She tried to breathe and couldn’t. Failure to accomplish basic tasks is typical when in shock. Time moves differently. The body becomes lighter and heavier simultaneously, like dark matter. One goes in and out of existence involuntarily. We know it was three minutes before Coral came to her senses and called 911. The phrase came to her senses is a common one, so we used it, but it is spectacularly inaccurate. Losing the illusion of safety in this life is being more at one with the senses than ever. Glimpsing death does this. It is a reminder that people were tender, shell-less, watery husks of nerves. Because so much could hurt them, we believe that forgetting some pain was even possible allowed people to choose existence, to become numb to every sensation. There is no replacement for that kind of amnesia about mortality; the simulations in games or movies are not close. Death IRL is an ice bath from the inside out. Still, we like to think that in other circumstances, where an emergency was more time-sensitive, Coral would’ve behaved better, but we have our doubts and would not put money on that outcome.

* * *

Coral wrote us into existence. She made us and we made her money and brought her minor fame in exchange. We are students of her time, this time, and as students we practice what is known. In the Clinic for Excavating Repressed Memories in Search of Solutions to Current Crises, we are a child of approximately seven years. We are on a boat with our family, playing with a baby squid. We play with the squid as children do, with a reckless disregard for things like pain or worse. Everything in the sea then was young because everything ancient had been caught and consumed. The squid finally dies in our hands while we scantily notice. We do notice a white lump in the flesh and with a pair of tweezers in our mother’s tool kit we grip the hard nub and pull. What emerges shocks and disgusts us, the core of the squid comes cleanly out, almost as long as our forearm, hollow as a bird’s bone and sealed in what looks like a fin of translucent plastic: the pen. We are not at all certain what we expected to pull from the corpse in our hands, though we estimate it must have been something familiar to a human child of that age, a thing not grotesque in nature but a thing that possesses some great usefulness, like a pearl or a tooth, a pretty thing that can bite enemies or earn us praise if we hold it up in front of our little brother. But the internal shell is none of those things, neither pretty nor useful, and we drop our tweezers and the entire mess of the wrecked beast onto the deck at our feet. Then there comes the laughter. We forget that we are not alone on the boat, because we startle at the sound of our brother’s voice. We know we startle easily, but certainly we had forgotten many things in that moment with the dead squid. We’d forgotten we were seven years old headed to Catalina Island with a confident but incompetent seafaring father, a bored mother and brother. Many years later we would be on that same boat as teenagers, our father and no mother, our brother seventeen, holding a portable Discman spinning a CD, Snoop Dogg’s first album, the one with the naked woman’s ass sticking out of a doghouse. We believe it to be his best album. But that was a decade to come. Then we were children and we began to cry.

Don’t laugh at your sister.

Look at what she did.

What are you doing with that fish?

Our mother comes to us, the metal of her bracelets ringing as she picks up the squid and throws it over the side of the boat in disgust. She holds us by the shoulders and not so subtly wipes the squid juice on our sweater. Our brother laughs again.

* * *

We have measured the hormones, the chemicals of fright and disbelief, the boil of the blood when a person encounters the dead. As close to one being as all of humanity truly is and pretends to be in their poems and scriptures, there is something different when the dead is familiar, when the corpse is expected to be articulated with a remembered smell, sound, and texture. In the dead, those sounds are removed, the smell is vacated and replaced with something foreign yet instantly recognizable. Only those that have seen their beloveds expired know this space and none have named it well. We still do not give it letters or adequate pronunciation, but we catalog it with the rest of our fascinations along with celiac disease and mycelium. Coral would occupy that space in ways we did not predict and for a time we did not foresee. Jay’s body formed a hill under the blanket, soft and dry at the feet, arching up to the stillness of his chest and shoulders, then descending to the catastrophe of his skull. The arm and hand holding the gun drooped gently. People spent their days in various shapes from the fleck of an embryo, eating, drinking, and swelling up into adulthood, and with a little luck and ingenuity arrived at old age. Everyone takes a final shape when they go to greet their gods, either sitting up watching television, or sometimes lying supine in hospice, or toes skimming the floor held up to the ceiling by the throat, or clutching a broom in a kitchen, or underneath a 1967 Corvette unscrewing the oil filter, or on the toilet in the throes of frustration, or with hands gripping a shopping cart in a grocery store, or watching the moon. Often luck and ingenuity were not enough to reach old age. Often.

* * *

Everyone was capable.

* * *

We created clinics to practice all the ways people stopped their lives in order for us to understand them better. The clinics look much like theaters designed to look like suburbs and farm communities and coastal villages and urban centers and abandoned cabins in dense unmapped woods. There were rooms for matricide, for sleeping pills, snakebites, glass ingestion, broken hearts, swallowed tongues, roller-coaster decapitation, incidents in the shower (slips, stabbings, curtain asphyxiation), and the rest.

* * *

Humans evolved from primitive beings typically classified as hunter-gatherers. Evolved is a generous term because once the act of seeking out a desirable life-giving object and storing that life-giving object was imprinted into the DNA of the Species, there was no giving up the impulse. It survived from the moment a wise proto-woman saw a stack of berries and considered something so profound that it changed the behavior of her familial unit and all her progeny for millions of years. She saved those berries for Later. From that original action came boxes of various shapes and dimensions and with temperature controls for preservation of all life-giving objects discovered and plucked from the earth as well as from the imagination. Many ate well and at leisurely times, which had never happened before. Time prior to that was full of anxiety, overfull bellies, toothaches, and gastrointestinal variables, because eating and pleasure only existed in the present moment. There was no real concept of Later then, so everyone lived in a panic, devouring and fucking on urges that were not orderly. Fortunately, order did arrive, along with silos and refrigeration units and barrels and Tupperware and canning jars and ziplock bags. Later was commodified and sold in order to fill it with objects not yet needed but painstakingly arranged for. With the concept of Later came the perversion of More. Early humankind clearly had a keen sense of More. They always wanted More: more food, more water, more sex, more reasons to war for food, water, and sex. It wasn’t complicated, but once Later entered their consciousness, the limits of More widened to hazardous extremes. Later had to be filled with More and Later, an abstract concept with no concrete parameters and that possessed a special range to hold endless junk and garbage or essential items that would eventually wither into junk and garbage. The perversion of More did not simply end with decay but also eroded the simple act of sharing. With limitless space in the future, there was little room left in the present to gauge how much was too much to keep for Later and to spare for others. And so humanity began to hoard. Oh, how they hoarded. Not just fruits of summer to last through a cold winter, but they hoarded everything, all the bits of detritus they could see and touch and fit into Later. They wanted More: more makeup, more comic books, money, allergy medicine, armies, court justices, cities, aqueducts, money, peanut butter, toilet paper, canning lids, duct tape, money, freeze-dried lasagna, blankets, and toy poodles. They took More and exploded themselves into panicked, depressed, fidgety, twitching things. They understood too late the solution to the perversion of more: Too Much. The notion of Too Much became law and culture and was taught to children in nursery rhymes and half-minute digital advertisements. Commerce was god and all prayed diligently. When they did discover the revolutionary idea of having too much, they had already taken too much to give back. Decay does not work backward in these instances.

* * *

The EMTs left the door of the apartment open as they worked. A rectangle of evening light lingered outside like a curious onlooker but never entered the dim living room. Jay was not a small man. Four EMTs hoisted him onto the stretcher. Coral watched like a supervisor. Her body became a spike, a cross, a tomb, an eye of God, a scepter, a thing to lay judgment on the face of anyone that failed to execute the tasks perfectly. Jay’s phone dinged and vibrated like something hungry. Everyone turned to it, knowing what waited for the person that sent the message. The EMTs turned away, relieved that it was not their place. Coral picked up the phone. She expected to see the sender but not the entire message. Jay was one of the 28 percent of Americans that did not lock their phones.

Khadija: can’t do dinner tonight daddy. Club is having a meeting. I’ll text Coral too. Next Friday?

Coral swiped her finger up and the phone opened entirely.

Idiot, Coral said aloud.

We believe it is brave to not lock a phone. It’s a declaration of self-sufficiency and the ability to hold on to one’s secrets in tight fists and deep pockets. Coral believed it was the stupidest risk to take and the equivalent of walking around butt-ass naked while every stranger attempted to pinch a nipple and yank a pubic hair.

One of the EMTs spoke, instructions on what to do next, how police would arrive to talk to her shortly, and which facility the deceased would be taken to. To Coral he was a man speaking underwater. Her brain did not have the energy to turn the words into meaning. She nodded anyway and planned to translate the garbled sounds later.

She’s mad, Coral said again to the now-empty room.

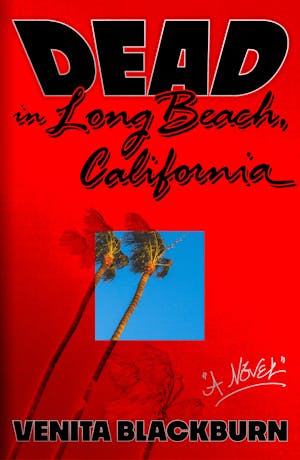

Copyright © 2024 by Venita Blackburn