SHE WOKE TOO EARLY. She’d gone to sleep late and woke during the night. Bars of light fell where the Chinese rug was frayed. The tassel at the edge of the gray curtain caught the glare like a rose in the sweep of a headlight. She had come home later than planned and had left her bag in the middle of the floor. Sometime in the early morning, a nightmare. She’d gone to shut the light off in the hall, but in her dream the light switch was illuminated; it was blue. She knew not to touch it. Between waking and sleep it wasn’t clear whether the door to the hall opened from the bedroom in the house where she lived now, where she’d lived for many years and had fallen asleep, the green room where across from the bed over the mantel was a print of a bird in a clutch of flowers, or was it the door from her childhood room that led into a room that was shared by her brothers? Upstairs the children were asleep, dreaming. Were the sleeping children her brothers, sleeping mouths open, one blond, one black-haired, like children in a fairy tale? Or were they her own children, knock-kneed even in sleep, ready to wake in an instant, to play the game saved for when a nightmare sent them bolt upright: What was your dream? Give it to me. She put out her hand. “There,” she said, “I have it.” She patted her pocket. George liked her to stroke his eyelids, a forefinger to the ridge of his cheekbone, a tiny scallop shell. No, it was the green room.

* * *

Caroline is standing by the north ball fields in Central Park in the snow. It is February. There is some kind of construction going on—or it was going on—the big yellow trucks have stalled, but still, she has had to circumvent them. She is walking southeast, toward Seventy-Ninth Street, through the park. It is freezing. The sky is pewter. The iron railings are so cold that she’s sure if she took her hand out of her glove and touched one, her finger would freeze in place. As it is, she’s stuck. Snow is drifting over her fur-lined boots. She is wearing a sheepskin coat and a fox-fur hat. Her aunt had given it to her. She said, when Caroline arrived at her door wearing the hat, “See, I was going to give it to the Guild for the Blind but then I thought, Caroline will wear it.” She is wearing it in the snow as she walks east and waits for Alastair to call her back on her cell phone, which she has set on vibrate and put inside her glove.

When Caroline first began to speak to Alastair on the phone thirty years ago, there were two ways to do it. There was a rotary phone in her tiny apartment that sat in a cradle like a blackened crab. When you wanted to make a call, or the phone rang, you picked up the receiver, and cradled it under your chin, placing one end by your ear and the other next to your mouth. Can I express the intimacy of this relationship, with the telephone? The round earpiece and the mouthpiece, identical, were perforated with tiny holes through which the sound entered and departed. The receiver was connected to the cradle by a black spiral cord. The cords could be different lengths. If the telephone had a long cord, you could walk around with the phone; if it was a short cord, you sat next to it while you spoke. In either case, you were tethered. The phone was attached to the wall at a special outlet, called a “telephone jack.” The plug was a little square of clear plastic. The round plastic dial of the telephone looked like a clockface. Like a clockface, numbers circled the dial. There were round holes in the plastic where you inserted your fingers to dial the numbers. Sometimes when Caroline was on the phone, she hooked her fingers into those holes.

The root of the word dial is dies, in Latin, day: dialis means daily. The medieval Latin is rotus dialis, the daily wheel, which evolved to mean any round dial over a plate. It is hard to convey now the heat of the old phone receiver, the curve of it on your mouth. If someone spoke into the receiver quietly, his lips would brush the tiny holes. There was the phone smell of plastic rimmed with overheated air. If you cut the cord, or the phone for some reason was yanked out of the wall, say, you saw that the wires inside the cord were brightly colored: blue, yellow, red, green. It was complicated, the business of talking. Caroline liked black phones. Usually, then, when the phone rang, it was Alastair, but to pick up the phone she had to be home.

The second way to make a call was to use a public telephone. There were phone booths on the corners of many streets. Always at the corner, never in the middle of the block. There were public telephones in drugstores and restaurants. You said to whoever was around, the girl behind the cash register, the man behind the counter: Can I use your phone? Or, if you wanted to use the telephone in the street and needed change, you asked if you could change a dollar for quarters, for the phone. The phone booths on the street were made of metal and heavy glass. Later in New York the phone booths became fewer in neighborhoods where drug dealers used them to schedule drops. Because of this you had to sometimes walk for blocks in the snow or the rain to find a phone.

It was warm in the phone booth and usually dry. Often people left things in phone booths: umbrellas, packages, wallets. They were distracted when talking on the phone, by what they were saying, or by what was being said to them. There was a bifold door to shut, for privacy. If you stayed too long in the phone booth, the windows fogged up; if you went inside after someone else had been inside a long time, it was foggy with their breath. The call was a dime, then it was fifteen cents, then a quarter. The public phones were rectangular, and there were three slots for coins on the phone, on the top; the slot for the dime was in the right upper corner. The receiver was connected to the phone by a cord. In the phone booth, the radius in which you could pace while you made a call was constricted; you shifted from foot to foot. In every case, no matter where you were calling from, there was a specified circumference, a radius, in which you could make a phone call, a certain distance and not more, from the place where the phone was connected to the earth, to the ganglion of wires that spanned out from the phone. Time was money. A long call cost more than a short one. When Caroline made a call from a telephone box, if it went on for more than three minutes the operator would come on the line and say, Five cents more, please. She scrounged for nickels, for dimes, later for quarters, in the pocket of her jacket, which had a hole. Coins slipped through and weighed down the lining as if she were planning to drown herself in the river.

When Caroline was a teenager, talking on the phone, it wasn’t unusual for the operator to break into a call: “Your father wants to get through on this line.” At the house where she went to the beach in the summer, there was a party line: five families on the road shared a number. If you picked up the phone and heard voices, the rule was: put it down. But everyone knew everyone’s business. Now there are ways to accomplish the same thing—the sense of being known; the world is a party line. Then people called “collect” when they did not have money for the phone, when they either did not have it or could not find the change. You could call the operator without a coin, and she would put the call through. In a “collect” call someone at the other end of the line picked up the receiver, and the operator said, “Caroline is calling, will you accept the charges?” What if he said no? The shame of it. There was no way to leave a message; it wasn’t until l986 that Caroline had an answering machine, which plugged into the phone and flashed a tiny little red warning light—then as now, there could be messages you did not want to hear. Along any road in the country the telephone poles stretched for miles, timber poles with wires looping over them, a chain stitch across the map, birds weighing down the wires, storms knocking them over. There were men whose job it was to repair those wires, sitting up on the poles. In the catbird seat. Up the mast. Gone now, the ruled paper lines the wires made in the air, music paper unfolding through the forests, on which voices sang, argued, planned, began, and ended things. A call from far away was a “long-distance” call. Because phones were rooted to the spot, if someone called you and you picked up, they knew where you were, and if you did not answer they knew you were not there, which sometimes meant that you were not where you said you were. In Manhattan, the phone numbers gave it away: CHelsea 3, MUrray Hill 7. Caroline’s exchange was TRafalgar 7. You could not say you were one place and be in another; location services could not be switched off. Birds perched on the wires, black notes, arpeggios. Standing in the park by the ball fields, Caroline had her cell phone in her glove so that she would feel it on her palm if he called.

In the same few hundred square yards where Caroline is waiting for a phone call—at a time that has been prearranged, which turns out to be a time when Caroline, who has forgotten her morning schedule completely, had an appointment on the East Side and is now, instead, standing in the park, freezing, as she did not want to answer the telephone, if and when it rang, on the crosstown bus, windows steamy with condensation, or in a taxi—Alastair is crouched in the dark, forty years ago, writing his name in the frozen dirt by the ball fields with a stick. He is fifteen. He is wearing a down jacket which is too small for him and which has been handed down to his brother, but he does not want to give it up, because he likes the way it smells. The feathers are coming out, pricking the nylon with little quills. Underneath he has on his school button-down shirt. The shirt is white, and a little grubby. The tails are out. His sneakers are wet from the snow. At school, in French class, they had been shown a film, L’enfant sauvage. He is underdressed for the weather, but he is thinking about the naked wild child, Victor, in Aveyron. Did he never have any clothes? How can that be? He imagines being naked in the woods, the cold puckering his body. He has looked up the weather in rural France. At night in the forest, it can dip below freezing. Alastair imagines the boy digging a burrow in the earth and covering himself with leaves. At the Museum of Natural History, where he had been taken by his nanny two or three times a week in the afternoons after school, there is a room where you can see mice and shrews in their lairs under the snow. There are little tunnels under the earth that end in sometimes large, intricate rooms, filled with treasures and food, old nuts, wizened berries. In one the mouse looks frightened, as if he (or she: was it a girl mouse or a boy mouse?) had just fled from something menacing on the crust of the earth over the burrow. That is what it looks like, in the cross section of the glass: the crust of the earth. It is fraying a little, like an old piece of toast, the hard dirt over the burrow, frosted with snow. Alastair named the mouse Mike. “Ssh,” he said to Mike, touching his nose through the tempered glass. “How ya doing, Mike,” his brother, Otto said, leering, making scary faces at the mouse. But Mike, who was stuffed, did not move. There was no taunting him. They did not know then that later, at least for a little while, it would be Alastair who would save Otto. There was no saving Alastair. In the park in the cold at eight in the evening on a Wednesday night when he has told his mother he is working on his project about batteries or tree sap with his friend Jason on Central Park West, Alastair moves away from the ball fields—he is now about one hundred yards from where Caroline is standing—and into a grove of locust trees, which later would shrivel. In a storm in l996 they were toppled by the wind and then cleared. Locusts have shallow roots. Under the dirt the roots are in the way, the roots are everywhere. Alastair has no tool but his pocketknife. He is thinking about Mike, and the wild boy, and the shape of the burrow he would make, like a canoe in the dirt. He wants to take off his clothes and cover himself with leaves. In the morning, he will wake up and everything will be quite different. The park will no longer be the park but another place in the woods. He will be on an island that has not been discovered by anyone, full of leafy trees and streams, and he will go down to the stream and drink water by cupping his hands. Little fish will swim through his fingers. His grandfather walked with him in the woods in the summer. If he was lost, he was to listen for the sound of water. If you were lost at sea and saw a bird, that meant you were near land. In the winter though, Alastair thought, the water is frozen and there is no sound. When he passed it earlier in the day the Boat Pond had a lid of ice. His pocketknife is ineffectual, and he nicks the blade on a locust root or a stone. He pictures the burrow in his mind and unbuttons his shirt, his hands moving onto his skin.

Caroline is standing in the snow. She is so cold that the phrase freezing to death enters her mind. She is wondering if she is standing in exactly the right place. She knows about the burrow, and Mike the mouse. She thinks about what she knows about telephones. When she dials a number, does it shoot up to a satellite and then back down? Ordinary telephone conversations have always been mysterious to her. By ordinary she still means the kind of phone call that is attached to a wall by a black snake of wire. She likes picturing the conversations shooting over the tendrils. In the film Sunday Bloody Sunday, a triangle of lovers leave messages for each other along those wires. The conversations are irradiated by color, red, yellow, green. For a long time, Caroline thought that she was the single woman in that film who pours yesterday’s cold coffee into her cup, stubs out her cigarette on the carpet, and is thwarted and betrayed by the man with whom she is in love, a mophead—it’s 1971—who makes light-filled glass sculptures and who also loves an older man who has a surgery in Harley Street. But she is wrong. In the film, the mophead betrays both of his lovers, but she has not been betrayed, because in her own life nothing has been kept from her: she simply wants something that is not there, which she has been told is not there, but she thinks if she keeps wanting it, her desire will be like water on a stone, things will change. A form of magical thinking, making something out of nothing. Caroline knows and does not know this. But she is in hiding under the mask of the woman who stubs out her cigarette, because she is also the man who makes glass sculptures which fill at dusk with blue light, a person who loves two or even three people at once. (Or, she used to be that person. Now she is not.) What she likes is theater, the glass tubes filling with light. Alastair knows this about her; he also knows that he can stop her heart, which he is doing right now, because he has not called and she is freezing to death, one hundred paces from where there was once a grove of locust trees, where in another diamond of time, he is trying to cut a root with his penknife, a present from his uncle Link on his tenth birthday. Snow is falling down around both of them. A jangle of bells. There is nothing more beautiful, said Frank O’Hara, in a poem whose name she cannot now remember, a poem with long lines, like telephone wires, than the lights turning from red to green on Park Avenue during a snowstorm. Park Avenue is about a ten-minute walk from where she is standing, with her phone in her glove, if she could move. But she is like a figure in a snow globe. (Now you ask, the first sign of you, to whom I am telling this story: Then, she also liked to talk on the phone? When I was a child, we used a gettone: “Non sei mai solo quando sei vicino a un telefono!” That was the slogan. “You’re never alone when you’re near a telephone.” Maybe yes, maybe no.)

* * *

In the story of the Snow Queen, two children love each other. Every time she reads it, it stops Caroline’s heart. The children are Gerda and Kai. The story is really about Gerda and Kai, but nevertheless it is the Snow Queen’s story, a cold stone at the heart of love, skidding across an icy pond. The children live quite close to each other in a town—they can climb into each other’s houses by jumping from terrace to terrace. Her father, too, went from terrace to terrace in Brooklyn, when he was a boy. He leapt, his foot in his leather shoe grazing the porch railing. Gerda lives with her grandmother. In the spring and long into the autumn there is a beautiful trellis of red roses on their terrace. Gerda and Kai both look forward every year to the time when the roses begin to bloom. The story divides in three parts. You take this one, says the fairy. That is the trouble with choices: they are one thing, or another. In the first part of the story, the devil himself makes a magic mirror that reflects everything beautiful in the world back as something drab and terrible; the translation from the Danish is peculiar: wet spinach. Can that be right? The devil is so proud of his mirror, he takes it up to heaven for the angels to admire, but on the way down, he drops it and the mirror shatters into a million pieces and falls to earth. Some of the shards are no bigger than a piece of grit. They float around still today, and get in your eye unexpectedly and make you cry. One day as Gerda and Kai are playing, it is autumn and the last roses are the most beautiful, cupping the faint sun in their petals, Kai gets a splinter in his eye. At first it simply blinds him. He asks Gerda to bathe it, and she runs inside for a cool cloth. But when his eye stops smarting, the sun has gone behind the clouds. Now, to Kai, the roses look like old shoe leather and Gerda is too stupid, with her damp cloth and her worried look. It begins to snow, large soft flakes as big as pinwheels. The snow piles up in the plaza. Kai takes his sled, which has silver runners. Gerda runs to put on her boots. He berates her for being so slow, and he jumps on the sled and leaves her behind. The snow is coming down unnaturally fast. There is a faint jangle of bells, and a sleigh appears, and the bells call to him, Come away. Come away, the bells said to Kai, when he looked up from his sled in the town square.

The sleigh is silver, and the woman driving it is barely visible in the gale, because she is wearing clothes which are made of cold moonlight. She is mad. Her bridle is made of pewter. Her white hair, streaming behind her, would reach the ground if she stood. Come, she says to Kai. Her voice is the only thing he can hear. It is not above the wind but inside it. It is made of spun sugar, that voice. His eyes hurt, and he tries to rub the grit out of them with his mitten, which is stiff with ice. The crystals rake his face, and he cuts himself above his left eye. The rose-red blood splotches the snow where, later, Gerda will find it. The voice speaking is the voice of the Snow Queen. Now, she says. Kai’s body strains toward the voice and as it does, ice enters him through the cut over his brow and he can no longer hold his sled with his frozen fingers. He has become a frozen silk thread pulled through the eye of a needle. The sled careens away from him and smashes at the foot of the elm tree in the center of the square, on the octagonal bench where in fine weather the old people sit and fan themselves. One of the runners is bent and a strut is smashed. Later, Gerda will take it to her uncle, the blacksmith, to see if he can mend it for Kai when he returns. But Kai is gone. When his sled fell from him, he gripped the lariat of bells on the Snow Queen’s sleigh, which are so cold they burn, and in an instant, he is on the sleigh, and the barbed wire lariat is tied tight around him, to no purpose because he is transfixed, it would not occur to him to get away. But later he will have welts on his back that will never disappear entirely, not even when he is an old man, living in the woods, writing, blind in one eye. But that is much later, we will not get to the end of the story for a little while. If thy right eye offend thee.

* * *

Caroline is a few yards from the now-gone theater of locust trees, where Alastair broke his knife—a nebula of star matter, a mouse in a burrow, a boy covered with leaves who loses the ability to speak, a conversation that hummed along loping wires, a few blocks from the museum, where under a high windowed ceiling, in a room named for a boy who disappeared in an upturned canoe, there is a row of nutmeg tree trunks, standing on end, their roots whittled to look like wings. The wild boy of Aveyron was born in 1788. There were sightings of a boy as early as 1794. A green boy, rather than a green man. A boy who had scars on his body, who was mute, who might or might not have been abused, who had no language. Would he have grown up to be a Green Man? In church architecture, there are three versions of the Green Man: the foliate head, completely covered in leaves; the disgorging head, spewing vegetation from the mouth; and the bloodsucker head, leaves sprouting from every orifice. Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, the medical student who cared for Victor, the wild boy, believed there were two things that separated humans from animals: the capacity for empathy and the ability to speak.

* * *

It is winter and there are no leaves on the locust trees. In the dark Alastair has given up hacking at the roots with his penknife to make himself a burrow. He puts his clothes back on. He is skating, he knows, on how late he can be, before there is a chance—a chance—that his mother will look up Jason’s number and call to find him, and then find out that Alastair has not been there, that Jason’s mother knows nothing about a battery project. There is little chance of this. Alastair is at Jason’s because Jason’s mother is not home, she goes out every night, and he knows that if Jason picks up the phone—if Jason is there, and not at his girlfriend Willa’s on Seventy-Second Street, whose parents are in London and whose housekeeper is dozing in front of the television in the maid’s room—he will automatically lie to Alastair’s mother, and say that Alastair has just left. He will lie without thought, like Pavlov, when he hears Alastair’s mother’s voice, which he knows, as he and Alastair have been friends since nursery school, he will automatically say that Alastair is not here, or wherever, or whatever he should be doing; Jason will represent Alastair as whatever he knows Alastair’s mother wants him to be: a boy who has just eaten macaroni and cheese for supper, made by Viola, the housekeeper, and finished his notes for the day on the battery project, tucked in his shirt, and zipped up his jacket before calling for the elevator man to take him down eleven stories so he could walk the few blocks home.

None of this will happen. Alastair’s mother is watching a production of Moonchildren at the Royale Theatre on Forty-Fifth Street. Then she will go to Elaine’s. She is wearing a peacock-blue shift with gold buttons and high-heeled black pumps by Delman, which she regrets wearing, because, of course, it is snowing. She is wearing a black wool trench coat, to the knee, and a hat that is very similar to the one that Caroline is wearing, forty years later, in the snow, a fox hat, while she waits for the phone to buzz under her glove. When Caroline and Alastair were small children, on different “game tables,” or on the floor in different cottages made of planked pine in the summer, they played board games. Parcheesi—the rules of which Caroline could never remember—Clue, Monopoly. The game she is thinking of now is Operation: the board was not exactly a board, but a pictograph of a human body, called Cavity Sam, with a red nose that lit up. At the beginning of each round, each player was dealt a “doctor card.” The goal was to remove the offending ailment from Cavity Sam, with a pair of tweezers, without knocking into Sam’s body. It was hard to do. The plastic parts fit snugly into the shapes carved out on his torso and arms and legs. If you were clumsy, Sam’s lightbulb nose lit up: out. The list of ailments included Wish Bone, Butterflies in Stomach, Writer’s Cramp, and Broken Heart. When a few days ago she had looked up the rules of this game, she found that by lingering on the word wish it appeared in yellow, as if in a smudge of butter. With a click, wish leads her to a song called “I Wish You Could Have Turned My Head (And Left My Heart Alone)” by Sonny Throckmorton, which in turn leads her to mercury, which can refer to an element, a planet, a Roman god, a rock star, and many other things. There is no end to it, she thinks.

When Caroline was eight, she was a Brownie for about five minutes. She wore a brown uniform which had a space above the left breast pocket for medals. She did not have breasts, and she did not stay long enough to win any medals. From those two weeks, she remembers only a tiny song and a rhyme, and a piece of aluminum foil that the troop leader had cut into a large circle and placed on the floor. The troop leader was her best friend’s mother, the only grown-up Caroline called by her first name, although she knew without being told that this was not allowed at Brownies. When Caroline took time to think about these weeks, she realized the circle of foil must have been a number of pieces of tinfoil, taped together; one thing Caroline knows about now is tinfoil. The Brownies met in the gym of the elementary school, or at least that is what Caroline recalls. Her memory can be faulty. As she remembers it, the tiny song went like this:

What have I in my shirt pocket, in a handy place?

I keep it very close to me, it can never be replaced

Even if you asked me thrice I know I wouldn’t tell

My Brownie Smile is mine for keeps—I asked the Wishing Well.

Her memory is faulty. She did not remember the name of this song, only the hum of it in the back of her brain, a place she avoids, a small room where certain buzzings are stored, hummings that sound like the beginning of wind from far off, a low hiss whose effect is to make her heart beat faster. When she was a child, her father sang her folk songs and nursery rhymes—In Dublin’s fair city, where the girls are so pretty. But when she found the song, her fingers clicking through the possible permutations: for who knew—sitting in the typing class where the desks were bolted to the seats, at the same desk she had dived under during an air raid drill, told to cover her head with her hands, over or under the braids, as her braids began, always, high up, over her ears—that everyone would become a typist, that it would no longer be a skill to “fall back on” if other ideas failed, that the keyboard on which her fingers walked into the labyrinth of herself would become for everybody, everywhere, a sort of acid trip to worlds circling worlds, the information carefully doled out so that unless you were skillful you were consistently led away from the main point? When she found the list of Girl Scout songs, split into categories, one of which was “Generic Graces”—an idea she found momentarily so enchanting and depressing that she had to pull herself away from it by force, as if bending a spoon—she knew it immediately: the “Brownie Smile Song.”

The song pitched Caroline back. Her mother had recently had her hair cut almost to her shoulders. Her braids stuck out. Her face was round. A mole on her leg was too high up to scratch. Caroline was a girl whose face was naturally solemn, to whom strangers in the street, even when she was small and walking with her mother, and later, certainly, when she was on her own, on the way to meet a friend or heading into the subway, said, “Smile!” or “Come on, a pretty girl like you, things can’t be so bad,” a girl at whom older women gazed, on buses and in coffee shops, with looks of compassionate inquiry (now that Caroline is older, she gives similar girls this look, and they burst into tears: she is under the impression that this is compassionate, which may or may not be so). The brute fact is that she has a transforming smile. She knows this because she has been told it over and over. It’s as if people know this, and when they ask her to smile, they want something of her—it still happens, and often she resents it. Do they want her to be transformed, or do they want to be transformed by her smile—or do they want for reasons of their own for Caroline to be happy, because it means she’s happy with them, which is another thing they want, and want the smile as evidence? All of which makes smiling, still, difficult for Caroline. Oh stop, I can hear you saying as you listen, idly, to this musing aloud, the second notice of you in this story, an appearance which is here simply a conduit for you to gesticulate, to say, Don’t be an imbecile, to say, Caroline likes talking so much that she complicates things for herself and everyone else, while you prefer silence—stare zitto. (Another link which also enchants Caroline, but which she has not tried, because she’s afraid she would never emerge, is Babylon Translator.) Recently she reread a story in which an unlikable character called Ninetta doles out her smile “like a precious jewel” and thought, not favorably, of herself. Recently, she has been doing this quite a bit, smiling, wrapped in a white terry-cloth bathrobe, the kind that is available for a price from hotels, sitting cross-legged in a tangle of sheets, drinking a tiny cup of coffee.

But at eight years old, Caroline was less—malleable. She did not give herself away easily. She didn’t know yet that it was impossible, it would never be possible, for her to give herself away, no matter how hard she tried: she was stuck with herself, and the smile song was about as close to an assault as she could imagine, then. She did not have a smile in her pocket; she did not want to put a smile on her face. None of that was exactly true. She did have a smile in her pocket, but it was not a real smile; it was a pretend smile. Now, that dichotomy is not one she would be so quick to recognize. It is a kind of splitting of hairs she has given up on. But at eight she had a need to orient herself, which is an attribute of Girl Guides and generals, and can lead to draconian measures. This isn’t entirely absent from Caroline’s makeup now, to perhaps the same unfortunate effect—that is, she has been wondering, lately, whether she is a fanatic. The smile song, that first week, was Caroline’s first inkling, the first dull roots of disappointment, that she would not stay a Brownie, and one day graduate, her chest full of medals, and become a Girl Scout. The smile song was Caroline’s cherry tree: she could not tell a lie. She did not have her smile in her pocket. Her concept of literature and history was deep but hazy, a vivid dream, a befuddlement that would remain, long past the time when clarity might have been expected; the cherry tree George Washington cut down was also the tree where Abraham raised the knife over Isaac and was stilled by the voice of God; it was the cherry tree which is cut down in the last scene of The Cherry Orchard, a thwack that many years later made her eldest daughter cry out “No!” in a movie theater on East Sixty-Eighth Street, where she had taken her girls to see a film of the play starring Charlotte Rampling as Madame Ranevskaya, and Alan Bates as Gayev. Non piangere sul latte versato? you ask me. Yes.

The rhyme was at the center of a story. There was a little girl named Mary, who lived with her grandmother. In many of the stories that were read to Caroline, and then those she read to herself and later read to her own children, a mother has been made to disappear, as if a maternal presence in itself kept stories from unfolding. These were stories in which she felt at home, but until many years later, when a friend said it was almost impossible to find stories with mothers—her own daughter did not want to read stories in which the mother was dead or absent—she hadn’t noticed this, as she herself had no mother to speak of, and until very recently had never identified with the mother in a story, only with the child, as if becoming a mother herself was almost accidental, like turning into a tree or a bird in a fairy tale. Her own children did not seem to mind stories in which the mother died, or disappeared on a long trip, never to return, or only to return after the adventure was tidied away, leaving with only a sharp glance meaning hush! across the table. In the Brownie story, there is no explanation why Mary goes to live with her grandmother—she just does. She has a brother, called Tommy, but he is not essential, indeed, in the poem he’s entirely forgotten. The phrase she used this morning to dismiss her youngest daughter, who had gotten up and was rubbing her eyes on the veranda, to look out at the palm trees (she had taken them, as she had been taken as a child, for a week by the sea in the middle of winter), was “I am working for half an hour and then I will be entirely yours.” Her children are the only people to whom Caroline has ever belonged entirely. Her own mother, if not wholly absent, was misplaced; in any case, she had never belonged to Caroline, even for a minute. In the story, Mary and Tommy are slovenly and ill-mannered. Their grandmother tells them about the Brownies, tiny people who are good and kind and helpful but who have left in despair, because they are too small to clean up the mess made by Mary and Tommy. Mary wants to see the Brownies, she wants to be a Brownie; she is a spoiled child, she stamps her foot. Her grandmother is firm: if Mary wants to see the Brownies, she must find the old owl who lives in the forest.

She listens for the owl hooting and follows the sound. The woods are dark and deep. When she finds him—the owl is an old grandfather, a troubadour of the woods, Churchill in a pith helmet—he gives her instructions. He laughs at her: it is a horrible sound, the owl laughing in dark trees. She must go down to the pond at the end of the lane when the moon is full. What she must do then, the owl says, is turn herself around three times, while saying verses for which he gives her the first line, but she must make the second line rhyme. Mary goes down the dark lane to the pond where muck grips her ankles. Frogs are calling in the wet dark. Moonlight skims the shiny water. What does she chant? Words Caroline learned, later.

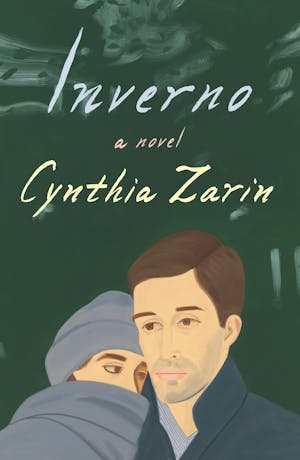

Copyright © 2024 by Cynthia Zarin