INTRODUCTION

I Have a Strange Relationship with Music

HIT IT OR QUIT IT #17, SPRING 2002

I have a strange relationship with music. It is strange by virtue of what I need from it. Some days, it is the simple things: distraction, entertainment, the sticky joy garnered only from Timbaland beats. Then, sometimes, usually in the part of the early morning that is still nighttime, most especially lately, I am painfully aware of every single thing that I need from music, embarrassed by what I ask of it. Having developed such a desperate belief in the power of music to salve and heal me, I ask big, over and over again. I have an appetite for deliverance, and am not particularly interested in trying to figure out whether it qualifies me as lucky or pathetic.

The stereo is just past halfway to as-loud-as-it-will-go, the rolling bass of Van Morrison’s “T.B. Sheets” (the first song on side two of the album of the same name) is moving throughout the house, its punctuating bump ’n’ grind ricocheting off the parquet floor, sound filling every room. This is the fourth night of the last five that I’m doing this same routine—lights out, alone, in a precarious emotional state not worth explaining, dancing—though in a way that is barely dancing—because lying down is out of the question on a night as hot as this, and lying down means motionless, and there’s really no being still right now.

Seven of the eight songs on T.B. Sheets are about Van Morrison and a girl he loves, who is dying of tuberculosis. I can count on one hand the times that I have made it through the entire album without crying. It’s brutal and never fails to deliver in its relentless humanity. Some songs detail the recent past, a golden reminiscence of some then-average day (“Who Drove the Red Sports Car”) that now will have to be enough for a lifetime; he’s asking her, “Do you remember?” insinuating some intimate exchange, some forgotten little secret. He needs her to remember. “Beside You” is a fierce, rambling pledge—he’s pleading for her confidence, in a torrential cadence of nearly unintelligible half sentences that sound like they could be directions someplace, before the decimating crescendo. He sounds drunk, a little off-key, hysterical, now saying everything he ever meant to say to her and didn’t, confessing himself, as if this act of deathbed desperation, this unbearable love, this compassion to the point of oneness with her, if she knew it, if she could really understand it, and take it in—it might just save her. All of this is cast out among ominous trilling B3 sustain and repetitive guitar, droning off into bottomless tension.

The title track, “T.B. Sheets,” is nine minutes and forty-four seconds of Van rending an exquisite topography of bleak human expanse, an outline of him collapsing under the weight of incontrovertible mortal pall, in a dialect too casual and acrimonious for how well he knows her. He’s unable to be of any use—unable to get far away fast enough from his fear, evading the knowledge of exactly what all this means, the finality of it. Details give way to a much deeper reckoning: “I can almost smell / The T.B. sheets,” audibly choking for air, and repeating, with frail cogency, “I gotta go,” over and over, like a mantra of absolution, he’s seeking another set of chances, burdened by survival.

But it’s too late, he’s in for all he’s got.

It’s a song of failure. It’s realizing that sometimes the best you’ve got to give isn’t much of anything at all.

Dancing in pitch-dark rooms, rooms illuminated exclusively by the tiny light on the turntable, fits very well with my ideas of rock-critic behavior, which is like normal music-fan behavior, but substantially more pitiful and indulgent. It’s behavior that comes from an inextricable soul entanglement with music that is insular, boundless, devoted, celebratory, and willfully pathetic. It’s my fantasy of what a real rock-critic scenario is like: a “special” manual typewriter, ashtrays full of thin roaches, an extensive knowledge of Mott the Hoople lyrics, a ruthless seeking for the life of life in free jazz sides. It may also include: a fetishizing of THE TRUTH (which always turns gory, no matter what records you listen to), detoured attempts to illuminate the exact heaven of Eric B. & Rakim or Rocket from the Tombs with the fluorescent lighting of your 3:00 a.m. genius-stroke prose, and, most of all, an insatiable appetite for rapture that cannot be coaxed by any other means.

It’s the exhaustive chronicling of what it is that artists possess that we mere mortals do not, what it is that they offer up that we are unable or unwilling to say ourselves. Offering connection to the disconnected, their songs make our secrets bearable in their verses and choruses: ornate in their undoing; gambling with their happiness, their personal irredemption, their humility; using failure to build a podium to reach god; their faked orgasms amid in-between-song skits; their solos, clever rhymes, crippled expectations, spiritual drift, still-unmet Oedipal needs, fuckless nights, not-so-gradual disappearance from reality, rodeo blues, unflagging romantic beliefs; being an outlaw for your love; a love supreme; Reaganomics; the summer they’ll never forget; the power of funk; hanging at the Nice Nice with the eye patch guy; American apathy; taking hoes to the Cheesecake Factory; getting head in drop-top Benzes; isolation; the benefits of capitalism; screwing Stevie Nicks in the tall green grass; the swirling death dust; the underground; and none of the above.

I want it. I need it. All these records, they give me a language to decipher just how fucked I am. Because there is a void in my guts that can only be filled by songs.

CHANCE THE RAPPER IS THE NEXT BIG THING FROM CHICAGO

CHICAGO, JUNE 2013

Chance the Rapper doesn’t want to go home. He just came from there, he says. The twenty-year-old rapper is in the passenger seat of my car. We were slated to drive around his South Side neighborhood, Chatham, where he grew up and now lives with his girlfriend. There is a flurry of excuses: It’s hot out. It will take too long and he has to be at the studio in an hour. The ’hood where he lives is just where he lives, he says. His story of how he went from half-dropped-out burner kid to Chicago’s next big thing, he insists, “happened here.” He gestures to indicate that here means exactly where we are—this few-block stretch of downtown surrounding the Harold Washington branch of the Chicago Public Library.

Despite his casual air and congenial charm, Chance is very aware of his image, his origin story, and how much it constitutes his appeal. Beneath his earnest demeanor lies an artist who has mapped every inch of his hustle. Chance is a favorite with high school kids, in part because his story could be theirs. He got busted smoking weed while ditching class at Millennium Park and spent his subsequent ten-day suspension recording a mixtape of songs that birthed his rap career. His is a ground-level stardom, someone fans can talk to when they see him on the train or in the street; he is someone they could ostensibly become. The young MC is very clear on the importance of his apocryphal tale and that is the only one he is inclined to tell. And so we will not begin our story of Chance the Rapper in Chatham, we will begin where he says it began: downtown.

We park and step out of the car outside of the Columbia College dorms. There is the waft of marijuana and someone yells, “Whattup, man!” A former classmate from Jones appears and pulls Chance in for a half hug, and explains, “He was the craziest motherfucker in school!” The old friend passes Chance his joint. Chance plugs his upcoming mixtape by title and street date. They exchange numbers after the kid offers his in case Chance needs a hookup for weed.

It is difficult to ascertain whether Chance is famous citywide, but in this six-block proximity of where we walk, he is the Mayor of the Underage. He is greeted constantly, by name, with handshakes, pounds, dap. He gamely poses for pictures, is offered lights for his ever-present cigarettes, and kids prod his memory to see if he remembers the last time they met—at the library, in the parking lot of their school when he was selling tickets to one of his shows, that one time their cousin introduced them.

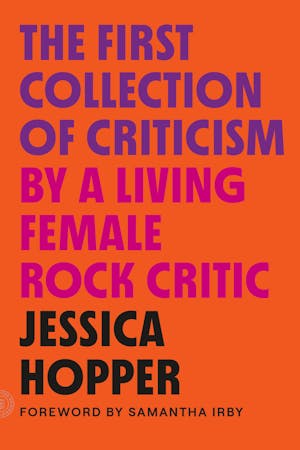

Copyright © 2015, 2021 by Jessica Hopper

Foreword copyright © 2021 by Samantha Irby