1

Caleb Altemoc brought the blade to his skin.

The donors were coming.

The camp slept around him, silent but for the rush of surf below the spirecliffs. The other tents, the great reclamation and replanting machines, the whole jobsite, might have been scooped up by a spirit’s hand and carried off, leaving him alone before his basin. But he was not alone. The Ajaian Mission of the Two Serpents Group was out there, counting on him to do his job.

He did not like to wake up this early, in the silver blue before dawn. When he was young he had loved these hours, but back then he crept into them from the other direction, sometimes drunk, sometimes high, trailing poker-hall fug. It had been a long time since he lived like that.

Once, years back, he had waked to this deep stillness, without the woman he’d gone to sleep beside. Mal had left him there on the waves, and gone to kill a god.

Early mornings were closer to each other than to the days that followed them. He felt as if he could slip through the silence between the years, a ghost haunting himself.

It helped to shave and dress. The razor found his edges, lifted soap from his cheek and jaw and left them smooth. His clothes would hide the deeper marks made by other blades.

A loud crack broke the stillness, then a rumble and crash. He twitched, cut himself. He recognized the sound: a spirecliff had fallen. The cut on his jaw stung. His bad leg ached. He toweled off, plastered the cut, and reached for his cane.

Tents hunched around him in the mist like sleeping beasts. Behind the olive canvas he could hear others stirring, his colleagues, his employees. Teo had been trying to get him comfortable with that word for years. They were dressing now, praying (those who prayed), waiting for teapots to boil, for water-treatment pills to dissolve. Their rustling movements might have been sounds from the guts of tent-beasts, digesting.

No alarm, no sentries, no screams. He was on edge, thinking about Mal. Spirecliffs collapsed all the time. Still, it never hurt to check.

Scar tissue in his leg pulled as he walked to the edge of the cliff. He could still feel his old wounds most mornings—the pieces into which he had been broken. The scars his father had left him pulled, too, and ached before storms, but the pain in his leg just meant that he’d survived.

Some days he did not need the cane. Some days he only needed it in the morning. He hoped this would be one of those days.

Teo would tell him not to worry. Donors weren’t investors, exactly. You didn’t have to sell them the same slick image. They want to see care, she said, they want to see the mission. They want to be purified by our work. That’s what their soulstuff buys. Or, if you don’t like buying, say: that’s what their wealth supports. You don’t have to play the brilliant young sociopath for these people. Be tired and virtuous and hurt. Be the man who left it all on the court.

(Teo used sports metaphors more than she used to. In one of the tempestuous interludes in her relationship with Sam—the time they’d broken up after Kavekana—Teo had dated, well, had a fling with, well, it was complicated but she had been, briefly, with Tollan, that Tollan, the ullamal player. They’d met in one of those thrown-together-by-fortune-on-the-run-from-the-Zurish-mob things, was how Teo explained it, though Caleb did not think that situation was common enough to be “one of those things.” When Teo told the story she would finish her drink—she only ever told the story while drinking—and say, “It was a weird, hot mistake, and I’m glad Sam and I worked our shit out. But it was a hell of a mistake.” People took all sorts of souvenirs from relationships. From Mal, Caleb had his cane. From Tollan, Teo had sports metaphors.)

At the cliff’s edge, Caleb found Ortega. The old man leaned against his lance, staring out at the other basalt pillars upthrust from the sea. Here, far from the golf ball, the spires looked almost normal: a uniform 112 meters tall, black stone jutting from the gray wild waters of what the Iskari who drew the maps had called the World Sea. No uncanny geometries in this rock, no faces, no black iron. Out here, the cliffs did not change as you watched. Unsupported, sleek, they stood until they fell.

“Boss.” Ortega pointed with his chin at a spirecliff they’d called Overbite, because its top had flared with a tooth-like shelf of rock. “Have to think up a new name.” A fissure cut across Overbite, sharpening its pillar to a stake. The fallen rock shelf lay wave-lashed below.

“I should check it out,” Caleb said. “Donors here today. Can’t be too careful.” His leg ached at the thought of the stairs down to the wharf.

“Jodi’s on it.” Ortega pointed again—Caleb saw the silver flash of a wingsuit circling.

“Still.”

A twitch of the old man’s pitted cheek passed for a smile. He would have been a good poker player, if he could draw better cards. “Teo said, ‘Make sure he does his job. Not yours.’ Let us work, hey? You make the skellies pay what it will take to fix this mess.” He nodded back toward the enormity of the site. Toward the golf ball. “I bet Jodi thinks she has it easier.”

Ortega had come to them in their second year, a dour veteran of border wars in Southern Kath. Caleb did not know his past. Not that Ortega was a quiet man. He talked a lot, told stories of love gone wrong, of mistakes with grenades, of duels and prison, of misadventures in every refugee camp and box canyon on the continent. But those stories never became a fabric. He never said where he was from, only that he had never fought for any government, nor bowed to any god, that his lance was always free. They’d met when Caleb was trying to heal an old God Wars battlefield on the pampas. Ortega had been so amused by Caleb’s claim that the Two Serpents Group wanted to fix things that he stuck around. “I have to see,” he’d said, “whether this is a trick. Some new poison of control. So I can kill you if it is.”

Caleb had thought at the time that Ortega was joking. After prolonged acquaintance, he felt less sure. That was one reason Caleb liked him.

“Tell me if Jodi finds anything.”

“Game tonight?” Ortega asked as Caleb turned back.

“How much of your soul do you have left?”

“Spent my whole life losing, boss. Shame to stop now.”

* * *

Caleb met the reporters by the golemwing deck.

Six of them had come together in a van from Alt Tizel, locals in beat-up linen suits who’d been upset when Ortega told them they couldn’t smoke in hazmat gear. He shook their proffered hands, the man from the Post and the man from the Telegraph, the woman from the nightmare wire, the chrome-masked revenant from the Thaumaturgist, and the shaved-headed society rag personage, who, Caleb imagined, would have claimed that their own suit was not in fact beat-up, but “artfully distressed.”

Caleb spoke about the spirecliffs and the project. He was brief, because the reporters weren’t interested. The Group had worked in the spirecliffs for years, reclaiming soil inch by inch. The cliffs, even the golf ball, were known atrocities. There wasn’t a story there. The reporters were here for the donor. So was he.

As Caleb spoke, he noticed the sixth reporter. Hard and nervous and maybe twenty, she stood apart from the nicotine fug of career journalism. Her eyes were bright blue, her gaze the dissecting kind. When his speech wrapped questionless and the others drifted to the coffee urn, she stayed.

No one had bothered to introduce her. An assistant, maybe. Teo said: Never overlook assistants. They keep planets in orbit and seasons in their course. He walked over. “You look like you want to ask something. It would make a nice change.”

She twitched as if startled from a dream, suddenly on guard. As if she hadn’t believed anyone would see her.

Over by the coffee urn, the woman from the nightmare wire chuckled at a joke she’d told. The man from the Post shook his head, slowly.

“I’m Caleb,” he offered. He shifted to face the sea, to give her space.

“D-Daniella. I didn’t mean…”

“It’s all right.” Poor kid. He’d been like that early in his career at RKC, the only person in any room who hadn’t killed at least a demigod in the Wars. Early career was tough, particularly when late-career folks tended not to die. “First big assignment?”

She laughed as if he’d said something funny or bleak or both. “That’s one way to put it.”

“You’ll do great. It might seem hard at first, but you’ll find your way.”

She hesitated, then: “This project—the Two Serpents Group—you built it. You brought these people together. You’re trying to heal…” She turned just a little, away from the golf ball and the deeper horrors of the cliffs. “You’re trying.”

“I’ve been lucky,” he said, “and I’ve had a lot of help. It’s hard to do anything alone. Anything worth doing, I mean.”

“Were you scared? At the beginning?”

The question surprised him, though not so much as the answer. “No.” He remembered the silence of waves, and the absence of after. “Before the Two Serpents Group, it felt like my life was over. So I was free.”

She crossed her arms, and looked away. “It’s never over.”

He didn’t know what that meant. He wanted to ask. But there was a mote in the rising sun, and then a pinprick, and then the mighty spread of metal wings.

He put on his game face and climbed to meet the donor.

* * *

Ever since the Group’s founding, Caleb had wondered: why did donors give?

Teo thought the answer was simple. Donor relations were an issue of sales strategy, not so different from her old work at Red King Consolidated. The Two Serpents Group wanted to heal wounds and mend the broken. To do that you needed funding. Who had funds? Deathless Kings, consortiums and Concerns, those gods that were left. So those were the people, loosely speaking, that you asked.

The problem was that most of those people, loosely speaking, had assembled their fortunes by causing the very damage the Two Serpents Group wanted to fix. If you were the sort of person who would kill a god in order to mine the necromantic earths beneath her holy mountain, would you really feel bad about the famine that followed, and the ghouls, and the wars and refugees caused by the famine and the ghouls? Would you feel bad enough to pay a large portion of your gains to fix what you had done?

Maybe, Teo said. Soulstuff might be fungible, but blood was sticky. Practically speaking, though, you didn’t go to Dame Alban, despoiler of Zorgravia, and ask her to fund Zorgravia’s recovery from said despoiling. You went to Ivan Karnov, legitimate businessman without any connection to Maskorovim soul trafficking in Iskar, and asked him to help the poor benighted people (literally benighted—Dame Alban having murdered their sun goddess) of Zorgravia, a region toward which Karnov’s utterly legitimate business partners had a level of personal affection and territorial ambition. Then you went to Dame Alban and asked her to help you rescue victims of Maskorovim soul trafficking in Iskar. And so on.

For Caleb, that math didn’t check out. You still had to convince people to pay soulstuff that might otherwise go toward expanding their yacht collection on ventures that wouldn’t benefit them personally. People who worried about the blood on their hands didn’t end up eating off golden plates.

It made sense, though, if he saw it as a poker table.

Players came to the table for many reasons. Some wanted to win, to learn the game of odds and risks, of reading bodies across the green felt. Others played to greet the goddess, to impress a girl or a boy, to test themselves, to show off. There were even players who wanted to lose. They bought into hands they should have dodged. They chased bets they knew they couldn’t win. Perhaps they wanted to show off all they had to lose. Perhaps they needed humiliation. Perhaps they wanted to pour themselves into the game, and never be enough.

To play well, you had to know why people played. And some players just wanted to pay.

So when he met donors, he looked for the shakes. He looked for the widening of the eye or inclination of the head, the restless betraying hands. The reason didn’t matter—guilt or ambition or fear, even a plain desire to help. If they had the shakes, Caleb had something to work with. If not, he was left with fairy tales and sales strategy.

Eberhardt Jax did not shake.

A Haight-Kepf golemwing brought him in from his yacht, along with his publicist and his PA and three security guards in carbon-weave pinstripe suits and wraparound shades. When Caleb closed his eyes to see the world of Craft, Jax was a nova. Beside him, the PA and publicist were wire-frame twists of soulstuff, and the security suits were not there at all. Stealth-worked glyphs? He didn’t know that was possible. But then, Eberhardt Jax was not known for respecting the bounds of the possible.

Jax did not look like someone who would need security. In a slim-cut blue wool Talon Row suit and white canvas sneakers, camel-hair scarf draped over his shoulder, he had the wondering expression of the early morning bird-watcher, alert to flashes of color in the canopy.

Jax was young for a donor. Caleb was used to pitching Deathless Kings. Jax didn’t just have skin in the game, he had literal skin. He was older than Caleb, though not by much, born of Shield Sea shipping barons and the cadet branch of some surviving post-Wars Ebonwald nobility, free of any chance of failure. What could someone like Jax want? Caleb wrote the morning off as a waste.

Then Jax stepped onto the landing pad, and changed. His eyes tightened, and his smile. His gaze flicked from Caleb to the twisted jobsite behind him. To the golf ball. He didn’t have the shakes. But whatever this was, Caleb could work with it.

Jax swept forward, hand out, smiling with teeth. “Mr. Altemoc. A pleasure.”

“Mr. Jax. Welcome to the end of the world.”

* * *

In glyphwork hazmat suits, they shuffled toward the golf ball. Caleb led, with Jax at his shoulder. Behind Caleb walked Ortega, his lance collapsed into a staff; behind Jax the three heavies. They refused to stay behind, so Ortega refused, too. He would have pulled Jodi and Sven off the security detail to bulk out their entourage, if Caleb hadn’t stopped him.

In whose party were the journalists? Count them for Jax, probably. Jax had invited them. When Caleb said he must be glad to see so many, though, Jax had laughed.

“I fear you misunderstand my relationship with the press.” Jax did not seem like he feared much, except rhetorically. “Even scavengers may seek live prey in time of need. I feed them when I can, so they do not look for other meals.” He waved to the reporters. A camera flashed.

Caleb caught Daniella’s eyes. She half waved, a quick movement.

“So you invite them,” Caleb said, “when you have a secret to keep.”

A tight smile played over the other man’s thin lips. “How would you describe your goal here, Mr. Altemoc? Land reclamation?”

“That was the reason we were brought in at first. No one else could make headway.” They crossed a steel bridge over a vast drop to the crashing ocean. “Craftwork wards decayed within hours. Miracles would expose the god to reprisal. No one wanted to take that risk, after what it cost Ajaia to stop the webs.”

“Webs?”

“We had to call them something. The more ordinary a word, the better. If you let the grand weirdness get to you, next thing you know you’re speaking in All Capital Letters.”

Jax glanced over the side of the bridge. “I thought it was well-coined.”

Below, thousands of cables thick as a weight lifter’s thigh spanned the gaps between the cliffs. They were not anchored to the rock—rather they plunged through its surface, and from their points of contact a rainbow-black metallic sheen spread gangrenous through the stone. The cables joined with other cables in the gaps, to form a network densely crosslinked, converging on the golf ball ahead.

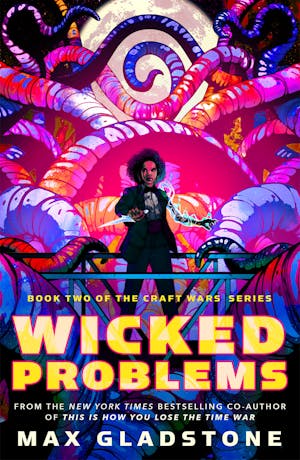

Copyright © 2024 by Max Gladstone