Book details

Winter Journal

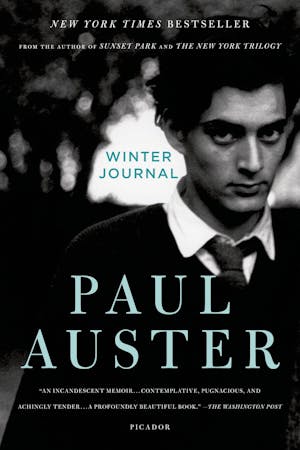

Author: Paul Auster

Winter Journal

$11.99

Winter Journal

Author: Paul Auster

$11.99

Buy This Book From:

Reviews from Goodreads

About This Book

"That is where the story begins, in your body and everything will end in the body as well."

On January 3, 2011, exactly one month before his sixty-fourth birthday, internationally acclaimed...

Book Details

"That is where the story begins, in your body and everything will end in the body as well."

On January 3, 2011, exactly one month before his sixty-fourth birthday, internationally acclaimed novelist Paul Auster sat down and wrote the first entry of Winter Journal, his unorthodox, beautifully wrought examination of his own life, as seen through the history of his body. Auster takes us from childhood to the brink of old age as he summons forth a universe of physical sensation, of pleasures and pains, moving from the awakening of sexual desire as an adolescent to the ever deepening bonds of married love, from meditations on eating and sleeping to the "scalding, epiphanic moment of clarity" in 1978 that set him on a new course as a writer.

Imprint Publisher

Henry Holt and Co.

ISBN

9780805095562

In The News

“As Auster escorts you through his life, you realize Winter Journal works like your own mind. It tells stories; it remembers, moves on, revisits; it sorts and classifies; it judges. Feels.” —Daniel Dyer, The Plain Dealer

“I find myself rendered nearly breathless by Auster's willingness to tell.” —David Ulin, Los Angeles Times

“[In Winter Journal] one of the nation's most revered fiction writers looks back at his life--and contemplates age and mortality--in a gripping memoir that hopscotches across the decades.” —Chris Waddington, New Orleans Times-Picayune

“An incandescent memoir....Contempative, pugnavious and achingly tender....A profoundly beautiful book...” —Washington Post

“This august author's meandering meditation on time, aging, and the eventual death of his mother beguiled many readers with its mix of pungent poetics and humble reminiscence.” —Elle Magazine, Readers' Prize Winner

“His concerns will be familiar to many readers, but because he is Paul Auster, he is uniquely able to reflect on them for the rest of us….Riveting…Writing in the second-person, almost as if talking about someone else or as if speaking with a stranger, Auster, oddly enough, establishes a powerful intimacy with the reader.” —Haaretz

“[A] graceful, moving new memoir...a kaleidoscopic reflection from one of our most important writers as he enters life's winter....Auster's brilliance is in how he makes his deep love for his subjects palpable....With Winter Journal, Auster has given us a remarkable mosaic of his mother and his second wife, the most vital women in his life, while, at the same time, allowing readers to catch glimpses of themselves in the expansive life that's woven together in this stirring memoir.” —Alex Lemon, Dallas Morning News

“Each year, when the inevitable hand-wringing begins over the American drought in winning the Nobel Prize for literature, I'm always surprised that more critics don't push Paul Auster....The recent knock against American literature is that it's ‘insular' and ‘isolated,' at least according to one grumpy Nobel Prize judge. As an antidote to those gripes, I'd like to press a few of Mr. Auster's books into more Swedish hands….Mr. Auster's prose is sharp and the plots are coiled. And best of all, his stories are addictively entertaining….Mr. Auster has written a spare meditation that's thoroughly entertaining. In short, Winter Journal might contemplate the past, but it reinforces Paul Auster's status as a writer at the peak of his talents.” —Cody Corliss, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Fascinating…Strikingly bold and original...Think of it as a literary cousin of Federico Fellini's semi-autobiographical film, ‘Amarcord' (‘I remember') -- only this time, we watch the protagonist grow up and become pensively aware of his mortality.” —Doug Childers, Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Paul Auster's novels are mesmerizing reverie, often chilly to the touch yet exploding with exponential warmth on deeper consideration. The same can be said for Winter Journal, a new memoir that comes three decades after his first, The Invention of Solitude. Here, Auster surveys the physical, emotional and spiritual landscapes of his life, then deconstructs these touchstones one unreliable memory at a time. Deeply musical, often darkly funny ruminations on baseball, becoming a middle-aged orphan after his mother's passing, the enduring power of love, and an intimate history of his own body's pains and pleasures weave together to confirm that while no one gets out of this world alive, each moment can be transcendent.” —J. Rentilly, American Way

“Readers of [Paul Auster's] string of beguiling novels, which include The New York Trilogy, The Brooklyn Follies and Sunset Park, will enjoy picking out the autobiographical roots of some of his fiction….Thoughtful ruminations on the nexus between the mundane and the meaningful, the physical and the emotional.” —Heller McAlpin, NPR.Org

“Unusual, affecting….To experience Auster's fixation on the body-- and his way of staging that fixation as something you're complicit in--is to realize that most memoirs don't work this way. Not even the ones that focus on illness and death. Memoirs tend to be psychological studies of how one person's mind worked through something. Winter Journal instead foregrounds the physical; on the first page Auster states his intention to catalog ‘what it has felt like to live inside this body from the first day you can remember being alive until this one.' With psychological interpretations stripped off, what's left is a more visceral accounting….What becomes clearer, and in its closing pages more potent, is the way this physical self-scrutiny amplifies his emotional responses.” —Mark Athitakis, Barnes & Noble Review

“[A] remarkable meditation on 'what it has felt like to live inside this body from the first day you can remember being alive until this one.' Notice his use of the second person? One of the first pleasures of Winter Journal is its feeling of immediacy, as if we are inside Auster's head staring with him into memory's mirror, listening to him talk to himself....Auster catalogs his memories with all the entertaining artistry of the best medieval poets.” —Alden Mudge, Bookpage (Top Nonfiction Pick for September)

“Winter Journal takes up the conceit of a detachable self and develops it...An engaging book.” —James Campbell, The Wall Street Journal

“Winter Journal is far more elegiac than angry, more wistful than soaked in regret....When you read Auster's final page, you will feel you have been in the company of a man whose life has had more ups than downs, more times to celebrate than memories to drown. Added pleasure will come from the clear, inventive prose that has marked Auster's equally inventive novels through the years, from his New York Trilogy to more recent books like Invisible and Sunset Park....When you reach the end of the book, you will have appreciated the journey as much as he clearly has.” —Dale Singer, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“An idiosyncratic memoir that is at times cerebral, at times bawdy, and in every sense consistently rewarding...Whether you experience what Auster calls the ‘journey through winter' literally or figuratively, this book will serve as a worthy companion when you embark on it.” —Harvey Freedenberg, Bookreporter.com

“A highly personal memoir and extended essay, shaped oddly and intimately by an all-embracing second-person voice.” —Steve Paul, Kansas City Star

“Auster's memoir recalls his free-spirited mother and the history of his own body. We experience Auster's appetite for food and drink and literature but foremost for sex, as well as the crippling panic attacks that plagued him after his mother's death, the epiphany he experienced watching a dance performance that cured his writer's block, and the intense shame of nearly killing his family in a car accident. Over time, as Auster's body alternately ages and is revitalized, the composition of these elements creates an intimate symphony of selves, a song of the body for all seasons.” —Vanity Fair

“The acclaimed novelist, now 65, writes affectingly about his body, family, lovers, travels and residences as he enters what he calls the winter of his life….Auster's memoir courses gracefully over ground that is frequently rough, jarring and painful…A consummate professional explores the attic of his life, converting rumination to art.” —Kirkus, Starred Review

“[A] quietly moving meditation on death and life…This is the exquisitely wrought catalogue of a man's history through his body.” —Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

“An intensely sensuous account of strange and dramatic events punctuated by jazzy lists of everything from the places he's called home to his favorite foods. Auster's most piercing recollections are anchored to injury and illness, close calls and bad habits, age and ‘the ghoulish trigonometry of fate.'…Auster is startlingly forthright, mischievously funny, and unfailingly enrapturing as he transforms intimate memories into a zestful inquiry into the mind-body connection and the haphazard forging of a self.” —Donna Seaman, Booklist, Starred Review

“This book is called a memoir, but as might be expected of the brilliantly offbeat award-winning author of The New York Trilogy, it's not a standard retelling of life events. Instead, as he approaches his mid-Sixties, Auster considers bodily pain and pleasure, the passage of time, and the weight of memory, stirring in reflections on his mother's life and death. High-minded readers will anticipate.” —Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal

About the Creators

Winter Journal

$11.99

Winter Journal

Author: Paul Auster