INTRODUCTION

ALL SHE HAD TO DO was walk into a room and crowds parted before the goddess. So thought a young filmmaker who watched one night in a bar as Candy Darling made the most stunning entrance he’d ever seen, “a Madonna wrapped in head-to-toe brown crepe.” When she lifted a cigarette to her lips, three men immediately extended flames to light it. She was ravishing.

It was April 1972, and Candy was nearing the pinnacle of her singular career. She wasn’t just a Warhol “superstar.” She would soon appear in a Tennessee Williams play, in a Richard Avedon photo in Vogue, in Lou Reed’s most iconic song, in a Werner Schroeter masterpiece opening at the New York Film Festival. All this at a time when few transgender people were even visible.

The twenty-one-year-old filmmaker—who went by the name of Dallas—was too shy to approach her that night, but a year later, Candy agreed to work with him when he asked her to star in his silent film Blonde Passion. He had created a production company, Immortal Films Inc., “dedicated to restoring Glamour and elegance to the American Screen.” Dallas told her he’d seen her for the first time in August 1967. That was a month before she opened in her first play, and he didn’t admit to his first impression of her: street queen, raunchy, bad teeth, and worse manners. She told him, “We don’t talk about then. Because it doesn’t matter who we were. Only who we are.”

And Candy had changed utterly. Now Dallas saw her as mythic, and his ambition was to present her as “a serious tragedian in the Greek mode.” As he explained in a piece written three years after Candy’s death, “Her myth, self-generated and self-perpetuated. Built on the solid foundation of Fantasy. She believed in it so totally that … it never dawned on anyone to ask her real name.”

When Dallas did finally ask one day for her “real” name, she didn’t tell him. Instead, she replied, “What’s real about a name?”

* * *

ONLY A FEW KNEW Candy Darling’s birth name during her lifetime. Most were either indifferent or too polite to ask. After all, she was part of a milieu where so many creative people, from Ultra Violet to Jackie Curtis, reinvented themselves behind new names.

But once upon a time, there’d been a child named James Lawrence Slattery.

Candy’s good friend Jeremiah Newton was one of those who knew that name. Jeremiah explained that while she never denied she’d once been “Jimmy,” Candy always spoke of him in the third person. “Jimmy used to…” instead of “I used to…” She’d broken with that identity.

So calling her anything but “Candy,” once she’d chosen that name, would have been rude and disrespectful, even back in the 1960s and ’70s. The terms “dead-naming” and “misgendering” did not exist during Candy’s lifetime. Nor did the words “transgender” and “nonbinary.” Homosexuality was illegal. So was cross-dressing. Candy predates many of the conversations about gender going on now.

She began her life as a tortured effeminate boy because she wasn’t really a boy. She was always she, and I will be using she/her pronouns for her throughout.

But, the name? An evolving trans movement hasn’t reached consensus about whether to even acknowledge the old name. Some trans people say: The life I lived as a gender that didn’t feel right under a name that wasn’t appropriate is part of my story and my struggle and don’t erase my history. Others say: The name I chose is my name for the duration of my life and to call me by the name and the gender assigned to me at birth invalidates my identity and that feels like an assault. As a biographer, I have had to ask myself whether I can really use the name that Candy hadn’t yet chosen when discussing her childhood. Isn’t it misleading? Isn’t it false?

What made sense to me in the end was to consider what Candy would have wanted. Her disconnection from her birth name, and her statement that “It doesn’t matter who we were. Only who we are”—these are imperatives I have to honor. So I am calling her Candy. However, her family and childhood friends spoke of her as “Jimmy” and “son” and “brother” and “he/him.” To change their words is to deny the context that surrounded her—the disorienting childhood she had to negotiate while living in a homophobic, transphobic world with a boy’s name and boy’s body. I have not sanitized that context. The two different names applied here during the chapters about her childhood illustrate the friction between who she really was and how she was perceived. And, of course, what’s real about a name? This is the story of becoming Candy.

The word “trans” implies a journey.

ONE“YOU SURE YOU’RE NOT A GIRL?”

SHE WAS THE BEAUTY QUEEN who didn’t belong and never had, never would.

By the end of her life, Candy Darling had succeeded in becoming the toast of a certain kind of town—more precisely, the toast of a certain part of a certain kind of town. And that had never included Massapequa Park, Long Island—her hometown. There, she always tried to obey her mother’s wish: “Don’t let anyone see you.”

Candy usually stayed with friends in Manhattan or Brooklyn. She never had her own apartment. But even when she was able to move in with a friend for months at a time, her mother’s house at 79 First Avenue* in Massapequa Park remained home base throughout her short life. She had to arrive and depart under cover of darkness. She could not answer the door or walk in the yard. Blinds were drawn. And when the taxi came to drive her to the Long Island Rail Road, she ran for it.

The Slatterys had arrived in Massapequa Park in 1957, as Candy was about to enter seventh grade. She turned thirteen that November. The only living witness to the years before that was Candy’s half brother Warren, who agreed to answer questions by email if I did not publish his last name. (Candy and Warren had different fathers.) In my one brief phone conversation with Warren, he spoke of not wanting his friends to know about Candy. In his emails, he skipped over many of my queries, explaining, “A lot of the answers to your questions after 65 years would be conjecture.” Nor would he give me permission to get her school records: “I do not know what his school records would reveal, and it was so long ago I doubt we could find them.” The school did find them but reported them “faint.” I began to see that as a metaphor. Candy had always been a phantasm in Massapequa Park.

Certainly, she left few traces. She did not have many friends, and according to the few I did find, she did not belong to clubs or participate in school activities. Her approach to life in the ’burbs was to try slipping through it in a plain brown wrapper. Only a few would see traces in young Candy of the person who later became so vivid.

But always there were the starry good looks. Terry entered her child in a beautiful baby contest at the Gertz department store, where judges awarded Candy the title of “Most Beautiful Baby Girl.” Warren did not recall that one, but said his mother also entered Candy in the Mirror Charming Child Contest when she was five. I couldn’t find any documentation, but I’ve seen the studio photos that corresponded with each contest.

Candy rarely spoke about the days when she’d been perceived as a boy. Even her closest friends picked up mere shreds of information. But it seems that secrecy was a family trait. When Jeremiah Newton decided, after Candy’s death, that he would write her biography, he interviewed some fifty people, including her parents—especially her mother, Theresa (known to most as Terry). All too often, Terry’s answer to a question would be, “Why do you have to know that?”

Candy’s father, John F. Slattery, was often called “Jim.” This seemed to be what he preferred, and effectively turned the child into his namesake when she was called “Jimmy.” Terry, however, usually referred to her husband as Mr. S.

As I began this project, Jeremiah turned all of his interview tapes over to me. A few of the cassettes were broken or missing, so we don’t have the beginning of this conversation about the early life of Candy Darling—born in Queens, New York, on November 24, 1944. Jeremiah is asking Terry a follow-up question as the tape begins: “So this situation increased, with your husband mistreating you and the two children? You would hide in your room while he’d be on his rampage?” When I spoke to Jeremiah more than forty years after this conversation, he could not remember what led up to this query.

But Terry responded to him with a story. The Slatterys were living in Forest Hills, Queens, in a second-floor apartment. Candy was still a baby, not yet able to walk. Warren was four, refusing to eat his dinner. This so enraged Mr. S that he picked Warren up by his shirt and dangled him over a banister. Terry remembered screaming, “Oh, please don’t do nothing to Warren.”

As she explained, “I had to beg him because, you know, he was really hot from drinking and he must have had quite a bad day at the track. He must have lost money. I could always tell when he lost … and he had a few drinks before he came home. He’d come in like a nasty—ready for anything, so we would just take it and not say anything, just hope that everything would all pass away, but no—it never did, because we’d always wind up in an argument. Me running outside with the children, out in the street, running around to my mother’s house.”

Terry’s mother lived on the corner and she’d lock the door against Mr. S, who would stand outside calling them names. “He would threaten our lives and we’d have to call the police,” said Terry. One night, Mr. S tried to push his way into his mother-in-law’s house and Terry’s brother met him at the door, picked up a small statue that sat on the porch, and hit Mr. S over the head. The resulting lump on his head didn’t stop him. He still stood outside, yelling. Terry called the police. “They came around and said, ‘Where’s the monster?’ And I said, well he just went into the doctor’s office and the doctor patched up his head. He had a couple stitches in his head. That still didn’t—I was afraid to go home. I didn’t go home for a couple of days.”

On this particular occasion, Terry went to a lawyer to start divorce proceedings and to see if she could prosecute Mr. S for assault. “I had a black eye, and my lip was puffed out and bleeding,” she said. “It was a mess. I had to wear a veil.” For the bus, she said. “So nobody could see my face.” She had temporarily lost sight in one eye.

Mr. S came to Terry before the divorce got to a judge, promising to change. He’d make it up to her and the kids. He was crying. On his knees. Begging. Terry caved and took him back. “I was very softhearted,” she explained.

Terry, born Theresa Phelan, worked for the Jockey Club at the Empire State Building while the Slatterys lived in Queens. She was a receptionist and office worker and “made friends with a lot of influential people,” according to Warren. “I think a lot of men were captivated by her beauty.” Warren thought his mother had probably helped his stepfather get his job. John F. Slattery worked as a cashier for the New York Racing Association at all the major tracks in the area. “It was a good living if he didn’t bet on the horses,” Terry told Jeremiah.

The Slatterys moved to North Merrick, on Long Island—in 1948 according to Terry, in 1947 according to Warren, or in 1946 according to Mr. S. As a veteran of World War II, he’d been able to purchase the home through the G.I. Bill. Once both children were old enough to be in school, Terry took a job as a bank teller. She had to work because Mr. S was still playing the horses. “He would be short at the end of the day as a seller,” she said, “and they would take it out of his salary at the end of the week.” Often he came home on payday with just forty or fifty dollars instead of the two hundred he’d earned. Off-season, when tracks closed, he tended bar.

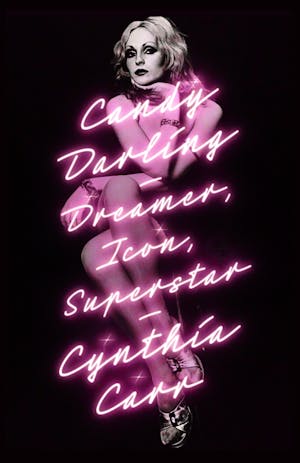

Copyright © 2024 by Cynthia Carr