“IN TROUBLE”

In the spring of 1960, with John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign hurtling toward an undecided Democratic convention in Los Angeles, Bobby Kennedy summoned his brother’s new speechwriter, Harris Wofford, into his office. Bobby, who managed Jack’s campaign, was famous for his irritability and his slashing ripostes. That day he was his typically blunt self and told Wofford that he would soon have a new role in the campaign: “We’re in trouble with Negroes. We really don’t know much about this whole thing. We’ve been dealing outside the field of the main Negro leadership and have to start from scratch.”

Secretly delighted by this assignment, Wofford sensed that he was being placed right where he needed to be. He was eager to start working under the successful Chicago businessman Sargent Shriver, a Kennedy brother-in-law whom Wofford had recently befriended. Shriver’s chief responsibility was heading up the Civil Rights Section (CRS) of the campaign, an initiative that had yet to produce any meaningful results. Wofford knew that they were starting from behind, working for a candidate with scant knowledge of how to bond with Black voters.

Making matters worse, JFK would be facing a general election opponent with a strong civil rights reputation. This is a Nixon long lost to American memory. Though it is overshadowed by his later actions, this Nixon prided himself on his moderate racial views. Vice President Nixon held an advantage with Black voters over Kennedy, at least when it came to his image. Nixon was seen by many of those voters as a more hopeful and sympathetic figure than the man he served, President Eisenhower. Nonetheless, in his 1956 reelection campaign, Eisenhower had still won nearly 40 percent of the Black vote, the most of any Republican since 1932, before FDR’s New Deal. Roosevelt’s economic programs won the Democrats a majority of Black votes outside the South, but southern cities (at least those in which Black voters were able to go to the polls) remained a different matter. The Democrats, after all, were the party that violently resisted Reconstruction, leading to the Jim Crow era. Segregationist Democrats were overwhelmingly supported by white voters across the South and reviled by Black voters in equal measure. There was an inevitable spillover effect to other parts of the country, and the CRS was trying to reverse the trend of Black Americans elsewhere once again voting for the party of Lincoln. Their task was made even more difficult by the perception that their candidate was a rich Massachusetts senator who had not been shy about forging connections with southern segregationist colleagues.

Although few Democratic operatives understood the hazards of their campaign’s disconnect with Black voters, the Kennedys were finally waking up to a simple truth: all Nixon had to do was improve on Eisenhower’s 40 percent, or simply come close to it, and he would be well on his way to winning the White House. Black voters remained the Democrats’ to lose outside the South, but it was nonetheless important to make inroads where possible and to stanch the loss of votes in the North and West. In light of Nixon’s popularity, it seemed plausible that he might even approach the threshold of 50 percent.

* * *

Though Wofford, in the years to come, would be dismissed by politicians as irritatingly idealistic, he was no fool. He knew Bobby’s dire assessment was correct. As former counsel to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Wofford had an unusual perspective on where both parties stood on issues of race. Yet as useful as his experience working for the commission had been, it was his role as an adviser on nonviolence to Dr. King that gave Wofford the most insight into the developing civil rights movement.

He knew that Nixon had personally forged a relationship with King, despite the minister’s youth, and that King was more and more at the center of a volatile national debate about racial inequality. Wofford sensed that King’s stated neutrality concerning the presidential race might not last for long, given the pastor’s meetings with, letters from, and seeming goodwill toward Vice President Nixon. Besides, King had been raised in Atlanta’s Black community, which for generations had gravitated toward the GOP. It did not help that Kennedy had over the course of his career displayed little interest in the realities of racial discrimination.

Finding himself unexpectedly appointed by Bobby to this new position in the Civil Rights Section of the campaign, Wofford thought it might be the perfect opportunity to help the Massachusetts senator understand the importance of encouraging if not a friendship, then at least an honest and forthright connection with King.

After Kennedy nailed down the nomination, Wofford increasingly stressed King’s potential benefit to the campaign, though he sensed he might pay a high price with the Kennedys’ inner circle in the future for doing so. Serving as the link between Kennedy and King would never be an easy role, not in this campaign season nor in years to come. Yet even as his efforts were met with resistance, Wofford did not despair; he sensed that King was becoming more responsive to Kennedy’s appeals. And King, for one, believed the Democrat surrounded himself with better advisers than Nixon did, and he included Wofford among those he called the “good people, the right people.”

King’s reservations about Kennedy himself were understandable; Wofford, too, felt some unease about the candidate he now worked for. While the young lawyer admired Kennedy for his wit, his quick intelligence, and his apparent capacity for growth, he had signed on to the campaign in order to move and to motivate Kennedy as much as to elect him. This dynamic was quite different from his devotion to King. Their connection had developed soon after Wofford read about the Alabama minister’s use of Gandhian tactics during the Montgomery bus boycott. When he heard how this young pastor was utilizing nonviolent techniques, putting into action ideas the young lawyer Wofford was speaking and publishing about, he resolved they should meet. He began sending King letters with his writings on nonviolence and solidified a working relationship when they met at a conference in 1956. Though never formally a member of King’s staff, Wofford offered blunt advice and editorial support for King’s 1958 book, Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.

Wofford was encouraged when the popular singer Harry Belafonte also advised Kennedy to seek out King. The candidate was recruiting Belafonte as a prominent Black supporter, but at their meeting the entertainer bluntly told Kennedy, “You’re making a big mistake if you think I can deliver the Negro vote for you. If you want the Negro vote, pay attention to what Martin Luther King is saying and doing. You get him, you don’t need me—or Jackie Robinson.” He added, “The time you’ve spent with me would be better spent talking to him, and listening to what he has to say, because he is the future of our people.” Suddenly Wofford’s advice was starting to look more and more prescient.

* * *

Wofford eventually succeeded in arranging two private meetings between King and Kennedy, one before and one after the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. King would later say of his first meeting with JFK, which took place in the lavish New York apartment belonging to Kennedy’s father, that he could tell the senator was bright but that he sensed little emotional commitment to addressing the depth of the injustices Black Americans faced. King noted that Kennedy “had never really had the personal experience of knowing the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the Negroes for freedom.” Kennedy had grown up without knowing many Black people and had not sought out knowing many more since then. Bobby would say later of racial inequality, “I don’t think that it was a matter that we were extra-concerned about as we were growing up.” But Wofford believed that Kennedy might well possess the capacity, perhaps because of his own family’s experience of discrimination toward the Irish, to develop an impulse to take action. King and Kennedy, so different in personality and attitude—one moral and somber, the other coolly ambitious and ironic—were at last beginning to forge some kind of connection, however awkward and halting.

During their second meeting at the senator’s Georgetown town house, King told Kennedy, “Something dramatic must be done to convince the Negroes that you are committed on civil rights.” Given the candidate’s spotty civil rights record and long-standing inclination to accommodate the segregationist sensibilities of southern Democrats, King was only expressing what many Black leaders felt. Kennedy did not disagree, nor did he bristle at King’s helpful candor. They agreed they should meet again as soon as the fall campaign began, perhaps in a public forum. Wofford got to work on making that happen.

Little did King know that his earnest admonition to Kennedy—that the candidate would have to do “something dramatic”—would play out with his own life in jeopardy.

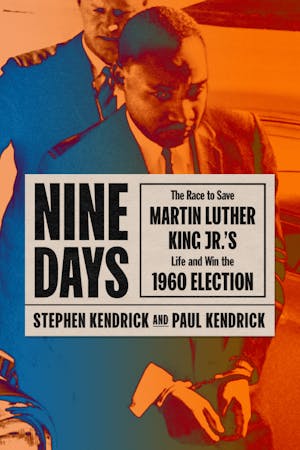

Copyright © 2021 by Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick