Chapter One

6.25 p.m.

Saturday, 7th of June 2014

The bar of the Rainsford House Hotel

Rainsford, Co. Meath, Ireland

Is it me or are the barstools in this place getting lower? Perhaps it’s the shrinking. Eighty-four years can do that to a man, that and hairy ears.

What time is it over in the States now, son? One, two? I suppose you’re stuck to that laptop, tapping away in your air-conditioned office. ’Course, you might be home on the porch, in the recliner with the wonky arm, reading your latest article in that paper you work for, what’s it…? Jesus, can’t think of it now. But I can see you with those worry lines, concentrating, while Adam and Caitríona run riot trying to get your attention.

It’s quiet here. Not a sinner. Just me on my lonesome, talking to myself, drumming the life out of the bar in anticipation of the first sip. If I could get my hands on it, that is. Did I ever tell you, Kevin, that my father was a great finger tapper? Would tap away at the table, my shoulder, anything he could lay his index finger on, to force home his point and get the attention he deserved. My own knobbly one seems less talented. Can get the attention of no one. Not that there’s anyone to get the attention of, except your one out at reception. She knows I’m here alright, doing a great job ignoring me. A man could die of thirst round these parts.

They’re up to ninety getting ready for the County Sports Awards, of course. It was some coup for the likes of Rainsford wrestling that hoolie out of Duncashel with its two hotels. That was Emily, the manager, or owner, I should say, a woman well capable of sweet-talking anyone into the delights of this place. Not that I’ve experienced much of those myself over the years.

But here I sit nonetheless. I have my reasons, son, I have my reasons.

You should get a load of the enormous mirror in front of me. Massive yoke. Runs the length of the bar, up above the row of spirits. Not sure if it’s from the original house. Ten men, it must’ve taken to get that up. Shows off the couches and chairs behind me all eager for the bottoms that are at this minute squeezing into their fancy outfits. And there’s me now in the corner, like the feckin’ eejit who wouldn’t get his head out of shot. And what a head it is. It’s not often I look in the mirror these days. When your mother was alive I suppose I made a bit of an effort but sure what difference does it make now? I find it hard to look at myself. Can’t bear to see it – that edge, you know the one I mean – haven’t you been on the receiving end of it enough over the years.

Still. Clean white shirt, crisp collar, navy tie, not a gravy stain in sight. Jumper, the green one your mother bought me the Christmas before she died, suit and my shoes polished to a shine. Do people polish their shoes any more or is it just me who practises the art? Sadie’d be proud alright. A well-turned-out specimen of a man. Eighty-four and I can still boast a head of hair and a chin of stubble. Rough it feels, though – rough. I don’t know why I bother shaving every morning when by lunchtime it’s like a wire brush.

I know I wasn’t what you might call good-looking in my day, but anything I had going for me seems to have long since scarpered. My skin looks like it’s in some kind of race southward. But do you know what? I’ve still got the voice.

‘Maurice,’ your grandmother used to say, ‘you could melt icebergs with that voice of yours.’

To this day it’s like a cello – deep and smooth. Makes people pay attention. One holler to herself pretending to be busy out there at reception and she’d be in filling my glass quick smart. But I’d better not cause any more trouble than I need to. There’s a job to do later and a long night ahead.

There’s that smell again. I wish you were here, to get it: Mr Sheen. Remember that? Every Saturday, our whole house smelt of it. Your mother’s day for the dusting. The sickliness of it used to hit my nose as soon as I came through the back door. I’d be sneezing from here to kingdom come for the rest of the night. Fridays now, Fridays were floor-polishing days. The waft of wax, homemade chips and smoked cod, warming my heart and making me smile. Industry and sustenance – a winning combination. You don’t hear of people polishing floors much any more either. What’s that all about, I wonder.

At last, a body appears from the door behind the bar to put me out of my thirst-ridden misery.

‘There you are, now,’ I say to Emily, a picture of beauty and efficiency. ‘Here to save me the embarrassment of getting the drink myself? I was even contemplating going to ask Miss Helpful out there.’

‘I got here just in time, so, Mr Hannigan,’ she says, with a hint of a smile, laying down a pile of papers on the counter, checking her phone perched on top, ‘we don’t want you upsetting the staff with that charm of yours.’ Her head lifts to look at me and her eyes sparkle for a second before settling on her screen again.

‘That’s just lovely. A man comes in for a quiet drink and this is what he gets.’

‘Svetlana will be in now. We were just having a quick meeting about tonight.’

‘Well, aren’t you very Michael O’Leary.’

‘I see you’re in fine spirits,’ she says, coming to stand in front of me, giving me her full attention now. ‘I didn’t know you were coming in. To what do we owe the pleasure?’

‘I don’t always ring ahead.’

‘No, but it might be a good idea. I could put the staff on red alert.’

There it is – that smile, curling up, as delicious as a big dollop of cream on a slice of warm apple tart. And those eyes, twinkling with the curiosity.

‘A Bushmills?’ she asks, reaching for a tumbler.

‘Make it a bottle of stout, to start me off. Not from the fridge mind.’

‘To start you off?’

I ignore the worry that’s crept into her voice.

‘Would you join me for one later?’ I ask, instead.

She stops and gives me a good long stare.

‘Is everything alright?’

‘A drink, Emily, that’s all.’

‘You do know I’ve landed the County Awards?’ she says, hand on hip, ‘not to mention a mysterious VIP who’s decided to book in. Everything has to be perfect. I’ve worked too hard for this to—’

‘Emily, Emily. There’ll be no surprises tonight. I’d just like to sit and have a drink with you. No confessions this time, I promise.’

I slide a hand across the counter, my offering of reassurance. Can’t blame the distrust, given the history. I watch it steal away her smile. I’ve never fully explained all that business with the Dollards to you and your mother, have I? I suppose in part that’s what tonight is all about.

‘I doubt there’ll be a lull,’ she says, standing in front of me now, still giving me the suspicious eye, ‘I’ll try to get back up to you, though.’

She bends slightly and takes a bottle of the good stuff with her expert hand from the fully stocked shelf below – one can’t but admire the neat order of the bottles, their harped labels all turned proudly outwards. Emily’s handiwork. She runs a well-ordered show.

A slip of a young thing arrives through the door to join her.

‘Great,’ Emily says to her. ‘The place is all yours. Here, give this to Mr Hannigan there before he passes out. And you,’ she continues, pointing one of her lovely long nails at me, ‘be nice. Svetlana’s new.’ With that warning she picks up her load and disappears.

Svetlana takes the bottle, locates the opener under the bar with a little assistance from my pointing finger, lays the drink and a glass before me then scurries to the far corner. I pour a bit until the creamy head hits the top of the tilted edge and then I let it settle. I look around and consider this day of mine, this year, these two years in fact, without your mother and I feel tired and, if I’m honest, afraid. My hand passes over the stubble on my chin again as I watch the cream float up. Then I cough and grunt my worries out of me, there’s no going back now, son. No going back.

To my left, through the long windows that reach the floor, I watch the cars go by. I recognise one or two: Audi A8, that would be Brennan from Duncashel, owns the cement factory; Skoda Octavia with the missing left hub will be Mick Moran. There’s Lavin’s jalopy parked right outside his newsagents. An ancient red Ford Fiesta. Gives me the greatest pleasure to park in that spot whenever I find it vacant.

‘You can’t be parking there, Hannigan,’ he’d shout, hanging out his driver’s window once he’d arrived back from wherever he’d been. ‘I can’t be expected to be lugging the deliveries up and down the town now, can I?’ His head’d be bobbing madly with that mop of wild hair, his car double parked, holding up the town. ‘Do you not see the sign? No parking, day or night.’

’Course, I’d be leaning against his wall, reading the paper.

‘Hold on to your tights there, Lavin,’ I’d say, giving the paper a good rustling, ‘it was an emergency.’

‘Is getting the morning paper considered an emergency now?’

‘I can always bring my business elsewhere.’

‘Oh, that you would, Hannigan. Oh, that you would.’

‘The newsagents in Duncashel has a coffee machine now, I hear.’

‘You can move your feckin’ Jeep on your way over so.’

‘Not one for the coffee me,’ I say, clicking open my door before getting in and sticking her into reverse.

It’s the simple things, son, the simple things.

It’s the end of the shopper’s shift it seems. Hands wave, horns beep. Driver windows are down with elbows sticking out, having the final chat before heading home with full boots to a night in front of the telly. Some of them might be back out later, of course, transformed into shiny things. Eager to show off the new outfits and hairdos.

I raise the glass and pour again until it’s full, ready for its final rest. My fingers, with their dark, crust-filled crevices, tap the side, to encourage it on. I take one last look in the mirror, raise my drink to himself there and swallow down the blessed first sip.

You can’t beat the creamy depth of a glass of stout. Giving sustenance to the body and massaging the vocal cords on its way down. That’s another thing about my voice, it makes me come across as younger. Oh, yes, if I’m on the blower it doesn’t let on that I host a hundred haggard wrinkles, or dentures that have a mind of their own. It pretends I’m a fine thing, distinguished and handsome. A man to be reckoned with. On that, it’s not wrong. Don’t know where I got it from – the only one in the family blessed with the gift. It was how I drew them in, those out-of-town estate agents; not that they needed much convincing, what with our farm being on the royal side of the Meath–Dublin border, the envy of all around.

But those boys with their swanky ties and shiny shoes couldn’t get enough of the place when I told them how far and wide she ran; nodding their heads, like those dogs in the back of people’s cars. Rest assured, I put them through their paces. Let no man try to take my money without earning every brass farthing. Walked the length and breadth of my land until they couldn’t see the colour of their shoes. All of them as eager as the next to get the business. No flies on them cowsheds, as my father would have said. I chose one in the end to sell my little empire to the highest bidder, Anthony Farrell. Had to be him – not because he impressed me with his patter, one was no different from the other in that respect. Nor was it the canny curve of his lip; it was simply that he shared your Uncle Tony’s name. Seventy years dead and I still idolise the man. Young Anthony proved me right in my choice, not stopping ’til he’d the house and business sold for a hefty sum. I closed her up last night, the house.

I’ve been packing up each room over the last year. A bit every day. I named each box so you’ll know what’s what: Maurice, Sadie, Kevin, Noreen, Molly – hers was the smallest. All that loading and lugging nearly killed me, though. Only for the young lads Anthony sent over, I’d never have managed. Their names won’t come to me now, Derek or Des, or … sure what does it matter? Mostly, I pretended to help; more the director of operations. They were well capable; you don’t expect that of youngsters too often these days.

I kept the essentials out ’til this morning when Anthony took the last box in his car. It felt strange, Kevin, letting it all go. The smallness of that final box sitting in his passenger seat caught me. Not that there was anything precious in it, just the kettle, the radio, my few bits of clothes, shaving gear, you get the picture. I threw out what was left in the skip I hired. The Meath Chronicles were the last to get chucked. Never without the Meath Chronicle for the local mart news and the GAA results, even though I’d have watched the games on the Sunday. It was the local and county matches that interested me most. I must’ve had six months’ worth of the thing piled up beside me on the sofa, in one big cascading mess by the end. Of course, when Sadie was around I’d have never gotten away with that. But, if I positioned them right, you see, they kept my tea at the perfect height. No sudden movements mind, not that there was any fear of that, I’m not as nimble getting off the couch these days.

Anthony is to store the boxes some place off near his office. Our lives in Dublin now – hard to believe. The important leftovers I have with me. In my inner breast pocket there’s my wallet, a pen and some paper for the few notes, given my increasing forgetfulness. In the outer ones I have the hotel room key, weighty and solid; my father’s brown and black pipe, never smoked by me but worn shiny and smooth from my thumb’s persistent rubbing; a couple of pictures; a handful of receipts; my glasses; your mother’s purse for her hairpins; my phone; and a couple of rubber bands, paper clips and safety pins – well, you never know when you might need them. And of course there’s your whiskey, out of sight, wrapped up in the Dunnes Stores bag at my feet.

You’ll be wondering about Gearstick, the dog. Bess, the cleaner, took him. Adam and Caitríona might be a bit upset by that. I know they loved playing with him on the trips home. Them with their leashes and him never been near one before in his life. Still he took it gracefully and walked under their guidance for the week or so you’d be around. A gentler soul, you wouldn’t find anywhere.

Do you remember your mother when I got him first? But sure you were long gone by then. She was all: ‘You can’t be calling the poor wee thing Gearstick,’ and him after chewing the gearstick in the car all the way home.

And I said:

‘Sure what does he care?’

That was the first and only time he was ever in the house. Of recent months I’ve left the back door open, trying to coax him in. He’d reluctantly step over the threshold into the back hall, poking his head around the kitchen door but only to let me know he was there. Panting, he’d wait in expectation of some outing or other. No amount of cajoling with a bit of Carroll’s sliced ham or even the fat of a rasher could bring him any further. I’d have been happy for him to sit with me as I watched the telly or even to just lie under the table when I was having dinner. But there was no budging him. I suppose I’ve not been afraid to raise a stick to him over the years so he wasn’t going to risk it. In the end, he just lay down and slept on the muddied mat, drifting off listening to the muffled sounds of my life.

The day Bess came for him, she brought the whole family, husband and three children. All stood around smiling at each other, me doing my best impression of one, nodding and pretending we knew what the other was saying. They’re from the Philippines; at least I think so, somewhere out foreign anyhow. The children bounded up and down the yard with Gearstick for a bit. He obliged, jumping and skitting alongside.

‘What he eat?’ Bess asked.

‘Anything you have leftover.’

‘Leftover?’

‘The dinner.’

‘You feed him dinner?’

‘What’s left, you know. A bit of bread soaked in milk, even.’

She looked at me, her brow contorting like I’d just farted. I could feel the will seep out of me.

‘Anything, sure. Feed him anything.’ I’d had enough. I stroked Gearstick’s ear and watched his head tilt and his eyes close one last time.

‘Good man. Go on now,’ I said, pushing him towards her but he wouldn’t budge. I patted his silky head then held my hand under his chin as he looked up, panting and eager, his tongue hanging out the side of his mouth. Everyone flashed before me in that moment: you, Adam, Caitríona, Sadie. Tiny snippets of the memories you’d spent with him. And I saw me too – him at my heel as we walked my fields over these past years. And I nearly said no. Nearly told Bess to turn her car around and leave us be. My eyes pleaded with Gearstick not to make this any harder but every time I inched away, he followed. What did I expect of that loyal soul, that he would just abandon me, like I was doing to him? My treason was a lump caught in my throat, refusing to be swallowed or grunted away. In the end, I could do nothing more than walk into the house and close the door. I leaned with my back against it, knowing that Gearstick was on the other side, looking up, watching and waiting for the handle to turn. I made myself move on through to the kitchen, refusing the temptation to look out the window as I heard the commotion of them trying to get him into their hatchback. Instead I kept on moving, mumbling away, trying to block out the weight of another ending, another loss in this worn-out life of mine.

I never asked where they live. Up in the city is all I know. In a walled back garden possibly, or worse, an apartment. I’m not sure Bess knows quite what she’s letting herself in for with a working dog like that. It was her or the pound; maybe that would’ve been kinder. I know I could’ve given him to any of the boys around here. They’d have been glad of a dog as good as him, but then they’d have known, wouldn’t they, that something was up. When Bess eventually drove away, I sat in the sitting room and closed my eyes, listening to the engine recede into the distance, imagining Gearstick’s confusion. I ran a hand over my face, my mouth opening wide, warning away the burn in my eyes.

’Course, this is the first you’re hearing of it all – the sale of the house, the land, the lot. I just, well … I just couldn’t run the risk of you stopping me. I couldn’t let that happen, son.

Svetlana’s inspecting the bar. Looking at the bottles one by one, checking the fridges, her finger touching labels as her hand passes over each brand. Her head nods and her lips read silently, memorising. Every now and again her eyes land on mine as she looks out at the room. She gives me a tight-lipped smile and I raise my glass a notch in her direction. Out she goes from behind the bar with a cloth to each table and dusts it down again. Can she not smell the Mr Sheen? Through the mirror I can see her hands make circular movements shining the already shined. She moves stools centimetres one way then back again. A real worker-bee, this one.

After Anthony left this morning I headed for Robert Timoney’s office. I’ve always said he’s a solicitor a man can trust. Not one for sitting at the bar spreading rumours. Every inch his father. Robert Senior knew a man’s business was no one’s but his own. Not that I’ve let him in on everything. Anthony sorted a solicitor in Dublin so I wouldn’t have to use Robert this time, didn’t want him getting suspicious over the house sale and lifting the phone to you. Up to now, all I’ve asked him to do is to sort the hotel room.

‘Is he around?’ I asked his receptionist when I arrived into his offices earlier. She’s a Heaney. You know her; you used to pal with the brother, Donal.

‘He shouldn’t be too long. You can take a seat there.’

I looked at the row of four black-cushioned seats, sitting right in the window, overlooking main street.

‘And have the world know my business? I’ll be in his office.’ I was already mounting the stairs.

‘That’s a private area, Mr Hannigan!’ she said, following me, her step echoing mine. Narrow stairs, no room for overtaking, I kept a steady, calm pace.

‘It’s locked,’ she added, at the top, all smug like.

‘No bother.’ My hand reached up over the door frame, finding the key and showing her. ‘All sorted,’ I said. Her indignant face disappeared from view as I shut the door and gave her my biggest smile.

‘That’s breaking and entering, you know. I’m calling the guards,’ she shouted through the door.

‘Super,’ I replied, from Robert’s chair, ‘I’ve a bit of business with Higgins, we can kill two birds with one stone.’

When she added nothing further, I tilted my head back and fell into a welcome doze as I listened to her thudding down the stairs.

‘Glad to see you’re making yourself at home, Maurice,’ Robert said, coming through the door not five minutes later, smirking, reaching for my hand. ‘’Course it’ll take me all day to pacify Linda.’

I’m sure, young Linda’s at home right now telling the same story to her father over the dinner. Him loving the roasting she’ll be giving me.

‘Robert, good to see you.’

I rose and began to round the table to the not so comfy chair.

‘No, sit, sit,’ he replied, taking the cheaper model. ‘True to your word, what? Not a day late. I’ve the key, here.’

He laid his briefcase down on the table, opened it and handed over a good old-fashioned weighty key that I put in my pocket.

‘Do they know it’s me that wants the room?’

‘A VIP, I said – “he’ll take nothing less than the honeymoon suite”,’ he laughed. ‘Emily tried everything to get it out of me.’

‘Good, that’s good. Listen, Robert,’ I said, a little more hesitantly than is my usual style, ‘I, eh, I’m moving into a nursing home over Kilboy way. I’ve sold the place and the farm to cover the costs. Kevin’s helped me. Found a buyer over in the States.’

You’ll forgive me, son, for including you in my deception.

‘What?’ he asked, his voice hitting a pitch that I’m sure only dogs could hear. ‘And when did all this happen?’

‘Kevin talked to me about it when he was over last. I thought nothing of it, thought he might forget the whole thing, if I’m being honest, but then out of the blue, about six months ago he calls me saying he’s found a buyer. Some Yank who wants a taste of home. And here I am now, the bank account bulging and my bags packed. I’m surprised he’s not called you. He said he would; mind you, he’s been up to his eyes with the newspaper, something to do with Obamacare. He will though.’

‘Well, now,’ Robert answered, looking at me a little put out that we never used him. ‘None of my business, I suppose, once all’s legal and above board and no one’s going to scam you.’

‘No. It’s all signed, sealed and delivered.’

‘I’d never have taken you for a nursing home man, Maurice,’ he said, not letting me off the hook that quickly.

‘I’m not. Just couldn’t take Kevin’s nagging any more. An easy life, that’s all I want now. It’s hard enough with Sadie gone.’ Tug at the heartstrings, son, works every time.

‘Of course, of course. It can’t be easy, Maurice. How long is she eh … gone, now?’

‘Two years to the day.’

‘Is that right?’ he said, looking genuinely concerned. ‘It doesn’t seem that long.’

‘It feels like a lifetime to me.’

His eyes moved away from mine as he started up his laptop.

‘’Course, I’m all for nursing homes,’ he said. ‘Book me in, I told Yvonne. Frankly, I can’t wait to be pampered.’

A man can say that at forty years of age, having the comfort of a wife and two kids at home.

‘So the honeymoon suite is your final farewell to Rainsford. Is that what the hotel and the room is all about?’

‘You could say that,’ I replied, taking a good look at the hotel, sitting across the road in all its sunbathed glory.

* * *

You know, I first came to work here in 1940 before there was any talk of it being a hotel. It was still the Dollard family home then. It was odd looking, they say, for what was a Big House in the country. The front door opening right on to the main street of the village, like you might see in a square in Dublin. The original owners must have liked the idea of having a village there to serve them, literally, right on their doorstep. No big gate, no long driveway – that was all to the back. Rows of trees, like stage curtains, ran out to the sides of the front of the house, marking the border of their land that stretched long and wide far out to the rear. Most of those trees are gone now, and the main street has extended to run round the hotel on the right, with a row of shops on the left. Any of the land not bought by the council for the town’s expansion is still there, but it’s not theirs any more, as we well know.

I was just a boy of ten, when I started to work as a farm labourer on the estate. Our land, my father’s land, I should say, what little of it there was then, backed on to theirs. My time under their employment wasn’t the happiest. So bad, that six years later when I left, I vowed never to darken their door again and wouldn’t have, had you and Rosaleen not been set on having your wedding here. Never understood your obsession, or Sadie’s for that matter. She was worse, going on and on about how magnificent it was and how luxurious the rooms were. Had me driven demented, with her gushing over the honeymoon suite. I thought the woman was going to have an attack of some description the day of the wedding fair. Of course, it could all have been an act, compensation for my lack of enthusiasm. I’m not one for pretending.

‘The original owner’s master bedroom, Amelia and Hugh Dollard, before the conversion,’ the function manager said, beaming away like this was somehow astounding.

That’s when I left you to it, heading straight for the bar. Sat at this exact spot and downed a whiskey, a toast to its demise. Don’t know who served me back then, not this young one, that’s for sure – in she wobbles now with a pile of glasses, God knows where she’ll put them, they’re stacked high already under the counters. I was never so engrossed in a drink in all my life that day. My head thought my neck was broken as I refused to look up, to acknowledge the place, or any of them for that matter, should they have been about. There were photos on every wall, in the corridors and rooms, taunting this hulk of a man with their history.

When you all eventually joined me, I bought the round, or should I say rounds, and listened to you rave about the chandelier in the banquet room and the view from the honeymoon suite.

‘You mean the view of my land?’ I said.

By then I pretty much owned every field surrounding the hotel.

‘And isn’t that why this place is just perfect? Looking out over the splendour of our farm. Your gorgeous rolling green hills, Maurice,’ Sadie said, placing a hand on mine. I’d swear she was a bit tipsy.

The review went on for what felt like hours. And all the time, I swirled my drink and tried to drown you out. Rosaleen’s family arrived then and off you all went on the tour again. That was enough for me. I left. Drunk as a fool, I drove home to sit in the dark.

To my utter surprise, though, I enjoyed your wedding, when it finally arrived. I suppose it was seeing you so happy, and Sadie too. I felt proud watching you take to the floor with Rosaleen for the first dance. And when we all joined you, me with Rosaleen’s mother and Sadie with the father, I caught your mother’s smile and laugh as she floated past. Later in the night, she even convinced me to have another look at that honeymoon suite.

‘Isn’t it just magnificent, Maurice? What I wouldn’t have given for this when we were married. Couldn’t you just see us now, Lord and Lady Muck?’

I danced her around the bedroom, nearly crashing into the dressing table, falling on to the bed. The drink had gotten the better of us. But my kiss was one of honest sobriety. Full of the love she had unleashed in me and gone on unleashing for all our years together. Not that we were the perfect couple. But we were good, you know. Solid and steady. At least that’s how it felt for me. I never asked her, mind.

‘I’ll book us in. Someday, I promise, we’ll have the honeymoon suite just for us,’ I said, lying on the bed, looking at her. I fully believed my words. I wonder did she? And here I am now, two years too fecking late.

She died in her sleep. She always said that when it was her turn to go, she’d like it to be that way. Just like her sister before her, there had been no sign of any illness, no complaint. She’d pecked me on the cheek the previous night, before turning over with her halo of curlers tied up in my old handkerchief. The woman had dead straight hair that she wound to within an inch of its life every night. All that bother, I used to think, as I watched her from the bed and her at the dressing table – what was so wrong with those silky lengths that I only ever glimpsed for a second? But, do you know something? I’d give my last breath right now to see her at that mirror one more time. I’d watch each twist and turn of her hand with complete admiration, appreciating every stroke.

That morning, I was in the kitchen with the radio on and my shaving already done before I realised I hadn’t heard the shuffle of her slippers or her usual humming. By the time I’d put the kettle on and still hadn’t seen her, I knew something was up. And so I let the newsreader’s voice trail after me as I made my way back down the corridor. Mick Wallace and his tax evasion. The image of that man’s white, wispy hair and pink shirt froze in my brain when I stood at our door and realised she was still in the bed where I’d left her.

Mick fucking Wallace.

I touched her face and felt the coldness of her passing. My knees buckled instantly. Collapsed at the edge of our bed, I looked at her face only inches away. Contented, it was. Not a care. Still a red glow to her cheeks, or am I imagining that? My fingertips felt the softness of the lines around her eyes, then found her hand under the blankets. I held it between my own, trying to warm it. Holding it to my cheek, rubbing it. It’s not that I thought I could bring her back to life or anything, it’s just … I don’t know, it’s just what I did. I didn’t want her to be cold, I suppose. She hated being cold. It’s one of the only things I remember about her passing and the funeral – that quiet time with me and her alone, no one else. Don’t ask me what happened after, who came or who said what, it’s all a blur. I just sat in my chair in the sitting room, still holding her hand in my mind – my Sadie.

I phoned you, of course. At least that’s what you told me when I admitted months after I couldn’t remember. I should’ve been alright for you when you and Rosaleen and the children arrived to say your goodbyes. I remember seeing your arms rise to hug me as I stood at the front door and them falling back by your side when you saw my face. You offered me your hand, instead. You clasped mine tightly, and my eyes concentrated on the two of them locked together until you let go. You touched my shoulder then, as you moved past into the hall. I can feel it there still, the only signifier that you were more than just another acquaintance who’d come to pay his respects. The shame of it. I wish now I’d wrapped my arms around you and cried on your shoulder and given you the chance to do the same. But no, I didn’t have the room for your grief as well as my own, it seemed.

What’s more, I shouldn’t have let you go home to New Jersey fretting about me. But I couldn’t rise to it, could barely rise at all for that matter. If I managed to get out of the bed, it was just to make it to my chair in the front room. There I sat with Sadie, walking through our lives together, until a cup of tea appeared in front of me, wrenching me back to my unwanted widowerhood. And I know you wouldn’t have returned to the States so soon after only for Robert convincing you that he’d look in on me and ring at the first sign of any problem.

You all came home again the following Christmas. We were to go to your in-laws, Rosaleen’s family, for the dinner. Good people, not that I made much of an effort with them over the years. I refused to go at the last minute.

‘Too much to keep an eye on,’ I said.

I knew they were only the half hour out the road but I couldn’t leave Sadie, not the first Christmas, it didn’t feel right. So you sent Rosaleen and the children on and stayed behind with me. Can’t even remember what we ate. Soup from the press, maybe. They came back a couple of hours later with two black plastic bags full of the kids’ presents and two tin-foil-covered plates of Christmas dinner.

Did I even manage to buy the children presents that year? That had always been your mother’s department.

That was the start of it, the first of the talk about the home. Well, when I say that, I mean the first time it was ever discussed in my presence. I’m sure it had been the topic of many a conversation before it reached my ears. Sure I knew it would come. What poor widow or widower living alone out there hasn’t dreaded its arrival?

‘Would you feck off,’ I told you out straight. ‘Wouldn’t I look the right eejit sitting in playing Telly Bingo with a load of old women in cardigans rather than out tending the cattle?’

In fairness, you laughed. That big, confident laugh – perhaps there’s something of my vocal genius in you after all.

‘Alright, Dad,’ you said, laying a hand on my knee, ‘we just thought you’d be safer there.’

‘Safer? What do you mean safer?’

‘Well, you just hear stories nowadays about people, you know, coming on to your property and—’

‘Sure isn’t that what this beauty’s for?’ I said, laying a hand on my faithful Winchester.

You looked bewildered. But I wasn’t giving up my life until I was good and ready.

As hard as it might be to hear, in a way I’m glad you live as far away as you do. I couldn’t stand the constant reminder that I must be a worry. I’d say your biggest fear is that I’d end up shooting some poor unsuspecting fool of a hill walker who might stumble on to the land.

Perhaps it’s a small consolation but I hope when you’re home you see that at least I’m clean. I manage perfectly on that score. I don’t smell, not like some I could mention. Old age is no excuse for stinking to high heaven. Sparkling, that’s what I am, having a good wash every morning with the face cloth and, of course, there’s the bath once a week. I had one of those rail things put in about five years ago and now I can lower myself in and out as easy as lifting that first pint. I’m not one for showers, could never take to them. Whenever I look at one I feel cold, that’s why I refused to have one installed despite your mother’s protests.

My greatest discovery of late has to be the launderette over in Duncashel that collects my offerings and drops them back three days later. Not like the local one, you wouldn’t find her doing anything as helpful as that. Every week Pristine Pete’s gets my business, sending me back my shirts, crisper and cleaner than Sadie could ever have managed, however blasphemous that might sound.

And what’s more there’s Bess, cleaning the house. Twice a week, never fail. Polishing and scrubbing it back to perfection. I think your mother would’ve liked her.

‘I’ll take your best cleaner with no English,’ I told the agency in Dublin, ‘I don’t want anyone local. I want someone discreet who’s not a gossip. I’ll pay extra for her petrol if needs be.’

She cooks too. Leaves me a couple of stews for the week. Mind you, they taste nothing like Sadie’s; in fact, I couldn’t tell you what they are. It took me a while to get used to them. Garlic, lots of that, apparently. But I surprised myself when I started to look forward to them, especially the chicken one. All that time with Bess, keeping me going, Robert was killed telling me I could’ve gotten the Health Board to foot the bill for a cleaner and gotten Meals on Wheels into the bargain.

‘Are you mad?’ I said, ‘I’ve never had a handout in my life and I’m certainly not starting now.’

Svetlana has sauntered over. Finished with her inspections and cleaning and glass stacking. She’s been pacing the bar for the last few minutes, waiting for the hordes to arrive.

‘You here for dinner later, yes?’

I like that name of hers. Svetlana. It’s straight up, sharp yet still has a bit of beauty about it. I wonder how I look to her? Nuts, no doubt. Sitting here, lost in my thoughts, the odd mumble escaping every now and again. She leans forward on the counter, eager for something to happen, even a lame conversation with the auld lad at the bar will do, it seems.

‘I’m not,’ I say, and it’s there I’d normally leave it. But tonight is no ordinary night. ‘Is tonight your first night here?’ I ask.

‘Second. I work last night.’

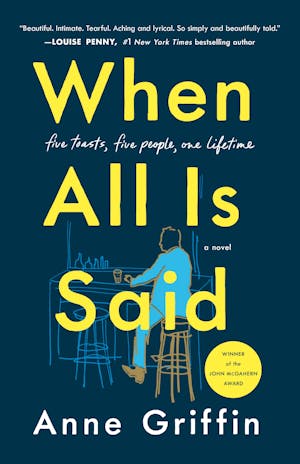

I nod, swirl the last drop at the bottom of my glass, before downing it. Ready now to begin the first of five toasts: five toasts, five people, five memories. I push my empty bottle back across the bar to her. And as her hand takes it and turns away, happy to have something to do, I say under my breath:

‘I’m here to remember – all that I have been and all that I will never be again.’

Copyright © 2019 by Anne Griffin.