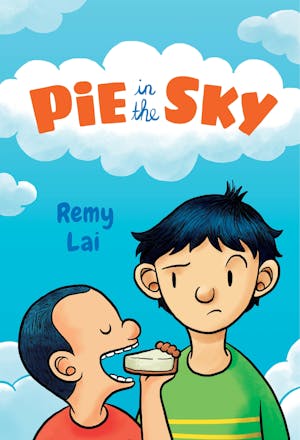

1

I look. The wing of the airplane slices through the fluffy cloud like a knife through cake. Sometimes, when the plane leans enough, I catch glimpses of the ocean. It’s as blue as the sky. Only the clouds make it clear that the sky is the sky. Then Yanghao sticks his oily face to the window, and my view is replaced by the back of his giant head.

I turn to the box on my lap. It’s pink and looks like a plain old box from a mom-and-pop bakery. The cake inside looks like a plain old cake iced with plain old cream and topped with plain old strawberries. But it’s the most special cake. Not a special of my family’s cake shop back in my old home, because this cake isn’t on the menu. My family usually only has this cake on our birthdays, but my grandmother made an exception. Ah-po handed me the box of cake through the window of the taxi and said, “Jingwen, you’ll be so happy over there that you’ll need to celebrate with this cake.” Goes to show that old people aren’t wise about everything.

A long time ago, which really isn’t that long ago but seems like from a time when dinosaurs roamed, I asked Ah-po if she and Ah-gong were coming along to Australia. She replied, “If we both go, who’ll run our cake shop?”

“Our cake shop will never ever close,” Ah-gong said, even though that day was a Sunday and our shop was closed, like on all Sundays. I asked him what if a giant meteor was hurtling toward Earth, or King Kong was on a rampage, or chickens became extinct so there were no eggs for cake making. He handed me an egg cake and told me to eat it while it was warm. Old people are sly at shutting kids up.

“We’re too old and set in our ways,” Ah-po said. And that was that. Once old people use age as a reason for anything, a kid can never come up with a reply that’s good enough. But she and Ah-gong truly did look sad that they weren’t coming. I wanted to tell them everything would be all right, but instead, I just split the tiny egg cake in half and watched short ribbons of steam rise out of it.

Ah-gong had the final word. “It’s so far away. It’s too long a flight.”

Of course, because Ah-gong is old, he is right, and this flight I’m on is definitely too long. Not just because of the thousands-of-kilometers distance.

Hours that seem like centuries later, Yanghao’s still going, “Looklooklook! A bathroom on the plane! Looklooklook!”

A shadow falls over the cake. I look up. A flight attendant is standing over me.

It’s the first time someone directly speaks to me in English. It sounds like Martian.

Oh wait, I think I caught the word “please.” But please what?

“Jingwen.” Mama puts a hand on my arm. “The flight attendant wants to store the cake in the overhead compartment. We’re about to land.”

I close the box and hand it to the flight attendant.

Mama says, “Thank you,” and I think the flight attendant replies, “Welcome,” but I’m not sure. The word is lost in some other words.

Suddenly it feels like I’ve been frozen in this sitting position for days. My back is tired, and my knees are sore. I straighten my legs, but my feet knock the seat in front of me. A woman’s face appears in the gap between that seat and the one next to it. She glances down at my feet. I squirm.

The cabin turns dim, and the plane shakes like I’m in my family’s Honda CR-V back home, driving our way along a street that’s more potholes than road. My ears hurt again like they did when the plane took off. I tell myself that everything will be all right, pinch my nose, and blow. Pop! Then the plane lands with a jolt like when our CR-V goes over a speed bump too fast.

Before the seat belt signs are switched off, people get up to retrieve their stuff from the overhead compartments. Mama follows, standing on tiptoes to reach for Yanghao’s and my backpacks and her handbag. She hands me the pink box.

Yanghao climbs over the seat dividers toward me.

I don’t want everyone on the plane to stare when he cries, and Mama will make me be a good older brother anyway, so I pass the box over. “Don’t drop it,” I say. Then I shout, “Don’t run! Don’t be a silly booger!” as he skips ahead of Mama and me down the rows of seats.

I’ve forgotten that little brothers only do the opposite, and I should’ve told him to drop the box, run like a wild moose, and act like the biggest booger. I’m stepping off the soft carpet onto the clickety-clackety floor of the rectangular snake that connects the plane to the airport when he says, “Ah!”

The next thing I hear is a plop!

All I can do is stare at the rainbow cake and let ridiculous thoughts run through my brain. Maybe it’s an omen, that we shouldn’t have stuck with the plan and come to Australia.

I want to yell at Yanghao, kick him when Mama isn’t looking. He’ll tattle, but it’ll be worth it. I also want to join his concert of tears, wails, and snot. But then I hear the people around us—those in front of us who have turned back upon hearing Yanghao’s cries, those passing by us, and those stuck behind us.

I’m on Mars.

2

Two months later, I’m still on Mars.

If I say that to Yanghao, he’ll say, “We’re on a bus.”

Because he’s only nine and still annoying.

If I say I’m on a bus on Mars, he’ll say, “We’re on a bus in Australia.”

If I say we’re on bus number 105 to Northbridge Primary School, which is in Australia, which might as well be Mars because to me English still sounds like an alien language even though we’ve been here for two months, and so everyone else is an alien and he and I are the only humans, he’ll say, “Jingwen, you’re a booger.” That’s what he always says when he runs out of lame comebacks.

So I say nothing. I just want to get us to school. Not because I’m a weird, school-loving kid, but because that’s my responsibility. During our first week of school on Mars, Mama rode the bus with us. One week of training for me to memorize the way: a fifteen-minute walk from our apartment to the bus station, followed by bus number 105, get off after nine stops, and arrive at Northbridge Primary School; do the reverse for home. Yanghao doesn’t need to do anything except follow his big brother like a rat following stinky cheese. Which is a bad analogy since I smell okay.

This going to school and back by ourselves is a big deal. Back in our old home, Yanghao and I never went anywhere beyond our own street without a parent or grandparent. I can also tell it’s a big deal from the way Mama took a million pictures of Yanghao and me on this journey through the suburbs. Well, not a million, because the memory card on our secondhand digital camera can’t store that much. But there are more pictures than anyone needs of Yanghao and me in our new uniforms, with our new backpacks, standing outside our apartment, waiting for the bus, tapping our cards to pay the bus fare, standing by the school gates, et cetera, et cetera. We were going to get the pictures printed and mailed by actual mailmen to my grandparents since they don’t do emails. So I smiled like a clown in those pictures. Which is also a bad analogy since clowns are freaky. Nobody would paint such big smiles on their faces unless, inside, they are terribly sad.

The bus turns a corner, and Yanghao leans into me. “Look-looklook,” he says, elbowing me even though he’s already gotten my attention. “Cake!”

“So what?” I say. “Have you never seen cake?”

Yanghao makes his are-you-for-real face. Which I guess I deserve because back in our old home, far away from Mars, our family’s cake shop occupies the front part of our house, the part that should have been the living room. We see cake every day, every minute, every second, even in our dreams. If there’s an apocalypse and we all turn into zombies, while everyone else is stumbling around looking for brains, my family will be the odd ones craving something different.

Copyright © 2019 by Remy Lai